- Submissions

Full Text

Surgical Medicine Open Access Journal

Same Story with Different Endings in HER2- Positive Breast Cancer: Why the Benefit of Pertuzumab is Robust in the Metastatic Scenario and Modest in the Adjuvant Setting?

Rafael Caparica1*, Adriana Matutino Kahn2, Daniel Eiger1 and Martine Piccart1

1Institut Jules Bordet, Université Libre de Bruxelles (U.L.B.), Belgium.

2Department of Internal Medicine, University of Connecticut, USA

*Corresponding author: Rafael Caparica, Institut Jules Bordet, Université Libre de Bruxelles (U.L.B.), Belgium.

Submission: December 20, 2019;Published: January 08, 2020

ISSN 2578-0379 Volume3 Issue2

Abstract

While the incorporation of pertuzumab to a chemotherapy and trastuzumab backbone (dual HER2 blockade) yielded a robust improvement in the outcomes of HER2-positive metastatic patients in the CLEOPATRA study, in the adjuvant setting the same magnitude of benefit was not reproduced with the addition of pertuzumab in the overall population of the APHINITY study, being the reasons for this discrepancy unknown so far. In the present manuscript, we discuss biological and clinical differences between metastatic and early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer that may potentially explain the different magnitudes of benefit observed with pertuzumab in the different disease settings.

Keywords: Breast cancer; HER2; Pertuzumab

Introduction

The addition of pertuzumab to chemotherapy and trastuzumab yielded an impressive improvement in the outcomes of metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer patients [1]. Intriguingly, the same magnitude of benefit could not be reproduced with pertuzumab in the adjuvant setting, being the reasons for this discrepancy unknown [2,3]. In this manuscript, we discuss clinical and biological differences between metastatic and early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer, and conclude by proposing potential explanations for the distinct magnitudes of benefit of pertuzumab in different disease settings.

Magnitude of Risk Reduction

When evaluating a new treatment in the context of a clinical trial, events occurring in

experimental and control arms are compared [4]. Early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer

patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy and trastuzumab had a 87.8% recurrencefree

survival rate at 6 years as per the recently updated results of the APHINITY trial [3]. In

the metastatic setting, however, the perspective is different: only 20% of patients receiving

chemotherapy and trastuzumab remain alive and progression-free at 3 years [1]. Therefore,

events are more frequent in the metastatic setting than in early-disease. In other words,

there is more room for improvement in metastatic disease, whereas in the adjuvant setting

chemotherapy and trastuzumab already yield high Disease-Free Survival (DFS) rates.

Illustrating this hypothesis, the addition of pertuzumab to trastuzumab and chemotherapy

in the metastatic setting yields a 32% relative reduction in the risk of progression, which

translates into an 8.2% absolute increase in Progression-Free Survival (PFS) at 3 years,

whereas in the adjuvant setting pertuzumab yields a 24% relative reduction in the risk of

recurrence at 6 years, translating into a modest 2.8% absolute improvement in invasive DFS

(iDFS) [1-3] . When considering only node-positive patients (who present a higher risk of

recurrence), the benefit of adjuvant pertuzumab becomes more pronounced (28% relative

reduction in recurrence risk yielding a 4.5% absolute 6-year iDFS improvement) [2,3].

In line with this rationale, the KATHERINE study showed improved 3-year iDFS rates with trastuzumab emtansine (TDM1) compared to trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer patients who did not achieve pathologic complete response (pCR) after neoadjuvant treatment (88.3% vs. 77.0%; p<0.001) [5]. Importantly, the KATHERINE study enrolled high-risk patients, who are expected to experience more recurrences than the population of the APHINITY study [2,3,5]. The different profile of patients enrolled in each study and the fact that T-DM1 may be more active in resistant disease may justify the robust benefit of post-neoadjuvant T-DM1 in the KATHERINE trial and the modest benefit of adjuvant pertuzumab in the overall population of the APHINITY trial [2,3,5].

Gene Expression

Breast cancer can be divided into four subtypes based on its

gene expression profiles, one of which is the HER2-enriched,

characterized by a high expression of genes involved in cell

proliferation and in HER2 pathway [6]. Concordance between HER2

status assessed by Immunohistochemistry (IHC) or Fluorescent in

Situ Hybridization (FISH) and gene expression classification is not

perfect: around 65% of HER2-positive tumors per IHC/FISH are

HER2-enriched, whereas 25% are of the luminal subtypes, and 10%

are basal-like or normal-like. Therefore, HER2-positive disease is

clearly a heterogeneous group of tumors [6,7].

HER2-enriched subtype appears to confer increased sensitivity

to anti-HER2 treatment, both in early-disease and in metastatic

settings [8,9]. Interestingly, primary tumors that are not HER2-

enriched can develop HER2-enriched metastases, suggesting

that HER2 expression may change as disease progresses [10,11].

Hypothetically, if HER2 expression becomes more frequent

as metastases are developed, a more pronounced activity of

pertuzumab would be expected in the metastatic setting.

The Immune System

After binding to HER2, trastuzumab and pertuzumab can

induce antibody-mediated cytotoxicity and ultimately promote

an anti-tumor immune response [12]. When an antibody binds

to its target, its Fragment crystallisable (Fc) region is recognized

by Fc receptors from lymphocytes and antigen-presenting cells,

leading to immune activation [13]. Modified anti-HER2 antibodies

with impaired Fc domains cannot induce an effective anti-tumor

response despite binding adequately to HER2 [14]. In contrast, the

activity of anti-HER2 antibodies is enhanced by Fc domains that are

more avid for Fc receptors [14]. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms

induce structural changes in Fc receptors, which can become

more or less avid for the Fc of anti-HER2 antibodies. Therefore, Fc

receptor polymorphisms may enhance or compromise the activity

of anti-HER2 antibodies.

Studies evaluating Fc receptor polymorphisms as predictive

biomarkers for the efficacy of adjuvant trastuzumab presented

contradictory results so far [15,16]. In the metastatic setting,

however, Fc receptor polymorphisms were correlated with

increased response to trastuzumab, and also with improved PFS

rates in patients treated with the anti-HER2 antibody margetuximab suggesting that immune activation may occur in different ways in

metastatic and primary HER2-positive breast cancer [17,18]. Given

the contradictory results observed in the metastatic and adjuvant

settings, Fc polymorphisms are not established as predictive

biomarkers in clinical practice.

Tumor Mutation Burden (TMB) represents the amount of

mutations per DNA megabase in a specific tumor [19]. High TMB

leads to the synthesis of abnormal proteins that can become

“neoantigens” recognized by antigen-presenting cells [19]. In

breast cancer, TMB is higher in the metastatic setting as compared

to early-disease, with HER2-positive and triple-negative subtypes

presenting the highest TMB values [20]. Thus, metastatic HER2-

positive patients have tumors with high TMB, and are probably

more prone to benefit from treatments that induce anti-tumor

immune responses, such as pertuzumab.

Baseline tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) levels are

correlated with prognosis in HER2-positive breast cancer patients

[21,22]. However, the role of TILs as predictors of anti-HER2

treatment benefit has yet to be defined: an exploratory study

assessed TILs levels in primary tumors and residual disease from 175

HER2-positive patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy

and trastuzumab: a decrease in TILs levels occurred in 78% of the

patients after neoadjuvant treatment, and was associated with

higher pCR rates (p<0.001). Intriguingly, high TILs levels (>25%)

in residual disease predicted worse survival (p=0.009) [23]. The

reasons why high TILs levels in residual disease may be a bad

prognostic factor in HER2-positive disease are unclear, although

it could be related to an increase in immunosuppressive cells and

a decrease in cytotoxic T cells induced by neoadjuvant treatment

[24].

Tumor Heterogeneity

Tumor cells that harbor a HER2 amplification have an

evolutionary advantage in comparison to HER2-negative cells,

since HER2-signalling constantly stimulates proliferation and

survival [25]. Interestingly, half of circulating tumor cells detected

in HER2-positive early-stage breast cancer patients do not express

HER2 [26]. Since the blockade of HER2 is the mainstay treatment

of HER2-positive breast cancer, the presence of tumor cells that are

not dependent on HER2-signalling may lead to treatment resistance

[26].

Assuming that most HER2-positive tumors present HER2-

positive and HER2-negative cells; and disease burden is higher in

metastatic patients; as HER2-positive cells have an evolutionary

advantage in comparison to HER2-negative cells, a dominance of

HER2-positive cells in the advanced disease may occur, particularly

in the absence of the selective pressure of systemic therapies.

A high proportion of HER2-positive cells may render the tumor

more sensitive to HER2 blockade, potentially explaining the more

robust benefit of pertuzumab in metastatic disease, especially if

we consider the high proportion of de-novo metastatic patients

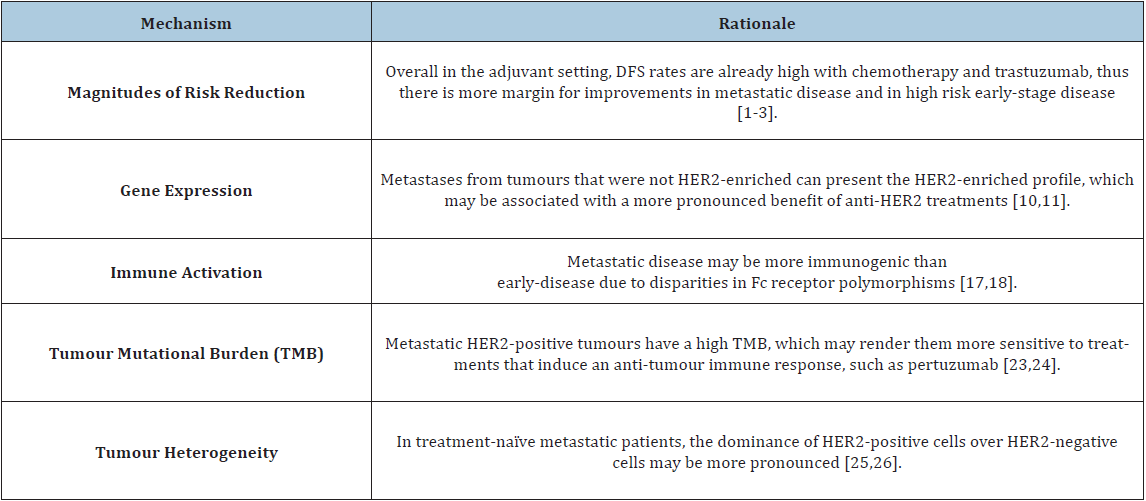

(53.4%) enrolled in the CLEOPATRA study [1]. Table 1 summarizes

potential reasons for the distinct impact of pertuzumab in the

adjuvant and metastatic settings.

Table 1:

Conclusion

No irrefutable data can explain the discrepant survival impact yielded by pertuzumab in metastatic and early breast cancer patients, and it is unlikely that one single factor will account for this contrast. Probably tumoral heterogeneity, gene expression patterns at distinct disease stages and differences in TMB account for the heterogeneous benefit of pertuzumab in HER2-positive disease at different stages of evolution. Also, since the induction of an immune response is a mechanism of action of anti-HER2 treatments, the host’s immune system and the tumoral microenvironment play also important roles. From a historical perspective, this is not the first time that a significant benefit in the metastatic setting cannot be reproduced in the adjuvant scenario [27]. These findings highlight the importance of evidence-based medicine: A strong biologic rationale and efficacy in the metastatic setting are not a guarantee that the results will be reproducible in early disease. Hence, it is important to have evidence from well-designed randomized trials to support treatment recommendations in each scenario. As the research to depict the molecular characteristics of HER2-positive breast cancer evolves, predictive biomarkers may arise to identify patients who benefit from pertuzumab.

Additional Information

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The present work did not perform any experiments with animals or humans; therefore no ethical approval or informed consent forms were necessary.

Consent to publish

The present work does not contain any patient data in any form; therefore no consent was necessary.

Conflict of Interest

RC has received speaking honoraria from Boehringer-Ingelheim and Janssen; and travel grants from Astra-Zeneca and Pfizer. AMK declares no conflicts of interest. DE has received an ESMO Clinical Research Fellowship funded by Novartis. MP is a board member of Radius; has received consultant honoraria from AstraZeneca, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Odonate, Pfizer, Roche-Genentech, Camel-IDS, Crescendo Biologics, Periphagen, Huya, Debiopharm, PharmaMar, G1 Therapeutics, Menarini, Seattle Genetics, Immunomedics and Oncolytics; RC, DE and MP have received research grants for their Institute from Roche/GNE, Radius, Astra-Zeneca, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Synthon, Servier, and Pfizer.

Funding

The present manuscript did not require any funding.

Author’s Contribution

All authors participated in all stages of the present work. The final version of this manuscript was reviewed and approved by all authors before submission.

References

- Swain SM, Baselga J, Kim SB, Ro J, Semiglazov V, et al. (2015) Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 372(8): 724-734.

- Minckwitz G, Procter M, Azambuja E, Zardavas D, Benyunes M, et al. (2017) Adjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in early HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 377(2): 122-131.

- Piccart M (2019) Interim overall survival analysis of Aphinity (BIG 4-11): A randomized multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial comparing chemotherapy plus trastuzumab plus pertuzumab versus chemotherapy plus trastuzumab plus placebo as adjuvant therapy in patients with operable HER2-positive early breast cancer. USA.

- Umscheid CA, Margolis DJ, Grossman CE (2011) Key concepts of clinical trials: A narrative review. Postgrad Med 123(5): 194-204.

- Minckwitz G, Huang CS, Mano MS, Loibl S, Mamounas EP, et al. (2018) Trastuzumab emtansine for residual invasive HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 380(7): 617-628.

- Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, et al. (2000) Molecular portraits of human breast tumors. Nature 406(6797): 747-752.

- Prat A, Carey LA, Adamo B, Vidal M, Tabernero J, et al. (2014) Features and survival outcomes of the intrinsic subtypes within HER2-positive breast cancer. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst 106(8).

- Llombart CA, Cortés J, Paré L, Galván P, Bermejo B, et al. (2017) HER2-enriched subtype as a predictor of pathological complete response following trastuzumab and lapatinib without chemotherapy in early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer (PAMELA): An open-label, single-group, multicenter, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 18(4): 545-554.

- Prat A, Pascual T, Angelis C, Wang T, Cortés J, et al. (2019) HER2-enriched subtype and ERBB2 expression in HER2-positive breast cancer treated with dual HER2 blockade. J Natl Cancer Inst.

- Stefanovic S, Wirtz R, Deutsch TM, Hartkopf A, Sinn P, et al. (2017) Tumor biomarker conversion between primary and metastatic breast cancer: mRNA assessment and its concordance with immunohistochemistry. Oncotarget 8(31): 51416-51428.

- Priedigkeit N, Hartmaier RJ, Chen Y, Vareslija D, Basudan A, et al. (2017) Intrinsic subtype switching and acquired ERBB2 / HER2 amplifications and mutations in breast cancer brain metastases. JAMA Oncol 3(5): 666-671.

- Collins DM, Donovan N, Gowan PM, Sullivan F, Duffy MJ, et al. (2012) Trastuzumab induces Antibody-Dependent Cell-mediated Cytotoxicity (ADCC) in HER-2-non-amplified breast cancer cell lines. Ann Oncol 23(7): 1788-1795.

- Vogelpoel LTC, Baeten DLP, Jong EC, Dunnen J (2015) Control of cytokine production by human Fc gamma receptors: Implications for pathogen defense and autoimmunity. Front Immunol 6: 79.

- Clynes RA, Towers TL, Presta LG, Ravetch JV (2000) Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in-vivo cytoxicity against tumortargets. Nat Med 6(4): 443-446.

- Norton N, Olson RM, Pegram M, Tenner K, Ballman KV (2014) Association studies of Fc receptor polymorphisms with outcome in HER2+ breast cancer patients treated with trastuzumab in NCCTG (Alliance) trial N9831. Cancer Immunol Res 2(10): 962-969.

- Gavin PG, Song N, Kim SR, Lipchik C, Johnson NL, et al. (2017) Association of polymorphisms in FCGR2A and FCGR3A with degree of trastuzumab benefit in the adjuvant treatment of ERBB2/HER2-Positive breast cancer: Analysis of the NSABP B-31 trial. JAMA Oncol 3(3): 335-341.

- Hope S, Mark DP, William JG, Javier C, Giuseppe C, et al. (2016) SOPHIA: Phase 3, randomized study of Margetuximab (M) plus Chemotherapy (CTX) vs Trastuzumab (T) plus CTX in the treatment of patients with HER2+ Metastatic Breast Cancer (MBC). J Clin Oncol 34(15_suppl): TPS630.

- Shimizu C, Mogushi K, Morioka MS, Yamamoto H, Tamura K, et al. (2016) Fc-Gamma receptor polymorphism and gene expression of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer receiving single-agent trastuzumab. Breast Cancer 23(4): 624-632.

- Chalmers ZR, Connelly CF, Fabrizio D, Gay L, Ali SM (2017) Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med 9(1): 34.

- Barroso SR, Jain E, Kim D, Partridge AH, Cohen O, et al. (2018) Determinants of high Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB) and mutational signatures in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 36(15_suppl): 1010.

- Denkert C, Minckwitz G, Darb ES, Lederer B, Heppner BI, et al. (2018) Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis in different subtypes of breast cancer: A pooled analysis of 3771 patients treated with neoadjuvant therapy. Lancet Oncol 19(1): 40-50.

- Luen SJ, Salgado R, Fox S, Savas P, Wong EJ, et al. (2017) Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in advanced HER2-positive breast cancer treated with pertuzumab or placebo in addition to trastuzumab and docetaxel: A retrospective analysis of the cleopatra study. Lancet Oncol 18(1): 52-62.

- Hamy AS, Pierga JY, Sabaila A, Cottu P, Lerebours F, et al. (2017) Stromal lymphocyte infiltration after neoadjuvant chemotherapy is associated with aggressive residual disease and lower disease-free survival in HER2-positive breast cancer. Ann Oncol 28(9): 2233-2240.

- Luen SJ, Griguolo G, Nuciforo P, Christine C, Roberta F, et al. (2019) On-treatment changes in Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TIL) during neoadjuvant HER2 therapy (NAT) and clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol 37(15_suppl): 574-574.

- Yarden Y (2001) Biology of HER2 and its importance in breast cancer. Oncology 61(Suppl 2): 1-13.

- Jaeger BAS, Neugebauer J, Andergassen U (2017) The HER2 phenotype of circulating tumor cells in HER2-positive early breast cancer: A translational research project of a prospective randomized phase III t PLOS ONE 12(6): e0173593.

- Kümler I, Christiansen OG, Nielsen DL (2014) A systematic review of bevacizumab efficacy in breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 40(8): 960-973.

© 2020 Rafael Caparica. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)