- Submissions

Full Text

Strategies in Accounting and Management

Strategic Control and Delivering Policy through Projects

Mike Bourne*

Centre for Business Performance, Cranfield University School of Management, UK

*Corresponding author:Mike Bourne, Cranfield University, College Road, Cranfield, MK43 0AL, UK

Submission:November 04, 2025;Published: November 12, 2025

ISSN:2770-6648Volume5 Issue 5

Abstract

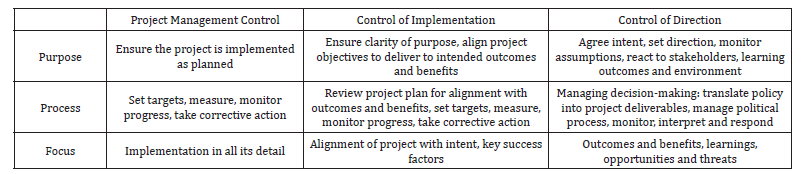

This paper discusses the use of strategic controls in projects. Drawing on previous work in the private sector by Muralidharan (1997) the paper proposes a framework for supporting the delivery of policy in the public sector. The framework outlines the purpose, process and focus for each of the three elements of control; these three elements being control of direction, control of implementation and project controls. The paper highlights why these three different elements are important and the different roles they play in successfully delivering the intended change.

Keywords:Strategic controls; Project controls; Policy implementation

Introduction

In the broader management literature, authors often talk about strategy formulation and strategy implementation. Formulation is about deciding, in broad terms, the direction the organisation will take over the next period. Implementation is about the planning and enactment of that strategic direction. There is a whole literature covering approaches and tools for developing strategy and even a literature around the process of formulating strategy. But, often, both academics and practitioners overlook the control of the strategy process itself. In larger firms there is usually a regular strategy cycle, often annual; but I have seen some companies using a three-year planning cycle (with one organisation I encountered on its 37th three-year strategic planning cycle). However, having a planning cycle doesn’t always mean that the process is controlled. It often just means that the strategy is updated every year. When it comes to undertaking that strategic review, there needs to be processes in place so that the review is timely, rigorous and aligned to the mission of the organisation. Also, in larger organisations, it is important for there to be consistency in the process right across the piece. The paper that really focuses on this is Raman Muralidharan (1997). In his paper, Muralidharan (1997) makes clear distinctions between control of strategy content, control of strategy implementation and management control. In his paper he discusses the purpose, process and focus of each of these three elements. The control of strategy content needs to respond to changes in the environment and emergence of new opportunities and threats as well as responding to invalid planning assumptions. Control of strategy implementation is focused on the implementation of strategy as planned, including setting timescales, goals and targets with regular monitoring of progress and corrective actions. The focus here is on key success factors. Finally, management control is focused on the implementation in all its detail. In his paper, Muralidharan explained how these elements work in practice with particular emphasis on the interaction and feedback between each of them.

Discussion

Working with central government in the UK public sector over the last decade, has raised the question “what are the strategic controls required for policy implementation?” Reflecting on multiple case examples of public sector projects, I believe there is a clear need to differentiate between control of direction, control of implementation and project management controls. Not to do so blurs boundaries and can result in lack of clear direction and transparency when thinks start to evolve or even go wrong. So, drawing heavily on Muralidharan (1997), I propose the framework outlined in Figure 1. In the public sector, policy is implemented through projects. Translating the policy into something tangible is often delegated by politicians to civil and public servants to implement. As with anything in life, implementing change is never certain, but good planning and implementation can improve the chances of success. Clarity of purpose and roles in the process is also helpful, together with a cross understanding between those setting direction and those implementing the project or change.

Figure 1:Controls and levels of control for policy implementation.

Ideally the implementation of policy should be guided by intent. What is the change the policy is trying to achieve? What are the desired outcomes and benefits? This should guide the design and implementation of the change. But in the world of public sector projects, there are invariably multiple stakeholders who have different views on what is to be achieved and how this needs to be delivered. Those with oversight of the project need to be constantly aware of the stakeholders’ views, the differences in their views and how these views develop over time. They also need to manage the planning assumptions they are making in setting the direction of the project. At this level the political process needs to be managed and combined with prompt decision making so that the direction is translated into project deliverables. Transparency is also important, especially as there are often uncertainties that need to be recognised rather than ignored. As the project progresses, the need for oversight and control of direction does not go away. Environmental factors, events, stakeholder challenges and implementation issues all impact the deliver of the policy and their needs to be continuing strategic oversight, drawing on feedback and learning as the project delivery progresses. The control of direction needs to inform the control of implementation. Here the project objectives need to be aligned with the intended outcomes and benefits. Implementation greatly benefits from clarity of purpose. This allows clear milestones and targets to be set, to monitor progress and key success factors to be identified. This enables flowing down the policy into deliverable activities on the ground. Finally, there is the level of project management controls, where the focus often turns to the Barne’s triangle (APM 2025 [1]), often called the iron triangle, comprising quality, cost and time.

As with the constant evolution in strategy formulation and implementation in private sector organisations, public sector policy initiatives frequently encounter the same evolutionary pressures. In the public sector this is exacerbated by the fact that there are multiple stakeholders involved creating complexity often resulting in goals and methods not being capable of being well defined at the outset [2,3]. These factors move projects from simply encountering technical challenges to facing adaptive challenges. Bourne [4] in their APM research report described these as fixed goal and moving goal projects respectively. Consequently, the implementation of policy and project delivery is far more fluid than many project management approaches recognise and there needs to be constant feedback and learning during implementation. This also requires those overseeing the control of direction to keep abreast of developments to ensure the delivery remains in line with the evolving purpose and intent.

Conclusion

To conclude, the purpose of Figure 1 is to distinguish between the three different levels of controls within a policy/project delivery setting. Project management controls need to sit within the wider setting of implementation controls. They cannot simply operate in isolation. Too often, reporting focuses on adherence to a project plan when, in reality, the project plan may have been overtaken by events or the project may no longer even be viable. Control of implementation oversees the project delivery, but the focus here needs to be on ensuring the continued alignment of the delivery with the evolving intended outcomes and benefits. This require maintaining good communications between the project delivery team and those responsible for control of direction. Finally, those in control of policy and overall direction have a responsibility to manage the wider stakeholder environment. Their role is to ensure that any changes in direction are managed in a way that has the least potential to impact negatively on the project delivery. This requires consulting with those overseeing the implementation so that the impact and consequences of changes are understood. It also requires decisions to be made in a timely manner, so that costs are not continuing to be incurred when they could have been avoided through prompt actions.

References

- APM Body of Knowledge, 8th edn (2025), Association for project management, Risborough, Bucks, England.

- Obeng H (1995) All change the project leader’s secret handbook, Financial Times, Prentice Hall, London.

- Turner JR, Cochrane RA (1993) Goals-and-methods matrix: Coping with projects with ill-defined goals and/or methods of achieving them. International Journal of Project management 11(2): 93-102.

- Bourne M, Parr M (2019) Developing the practice of governance, association for project management, Risborough, Bucks, England.

© 2025 Mike Bourne. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)