- Submissions

Full Text

Strategies in Accounting and Management

ESG Criteria & Executive Directors’ Compensation – Focus on Directors of the French CAC40

Viviane de Beaufort* and Hichâm Ben Chaïb

Professor in European and Comparative Law, France

*Corresponding author:Viviane de Beaufort, Professor in European and Comparative Law, France

Submission:August 22, 2024;Published: September 27, 2024

ISSN:2770-6648Volume5 Issue1

Abstract

This study, conducted by the European Centre for Law and Economics (CEDE) at ESSEC, analyses the integration of ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) criteria into the remuneration policy of executive directors (DMS) of the CAC40, utilizing research carried out within the Women Board Ready ESSEC programme in 2023. In response to growing extra-financial challenges, the remuneration of DMS has evolved to include ESG objectives, aiming to encourage a serious consideration of these criteria in the strategies of major corporations, alongside the evolving legal framework. The inclusion of ESG criteria in remuneration packages is now a widespread practice among large European companies, though the weighting and nature of the criteria used vary significantly. Reports from the Responsible Investment Forum (FIR), based on annual questions during shareholder meetings of major corporations published between 2020 and 2024, show a growing trend in the integration of ESG criteria into the remuneration policies of CAC 40 companies. In 2023, 842 written questions were posed during general assemblies. Within the Women Board Ready ESSEC programme, participants of the 2023 cohort worked on addressing disparities in the application of ESG criteria. While 100% of CAC40 companies have included ESG criteria in short-term variable remuneration since 2022, the ESG component in variable remuneration is 19.6% and 19.8% for the short and long terms, respectively. Only 23 CAC 40 groups provide a detailed breakdown of ESG criteria for the short term, and only 16 do so for the long term. This study also notes an imbalance in the types of ESG criteria considered, with a predominance of environmental criteria over social and governance criteria. Companies need to ensure that prioritized ESG indicators are clear, detailed, and aligned with meaningful performance objectives. The inclusion of ESG criteria in compensation packages is now a widespread practice, but the weighting and nature of the criteria used vary significantly. To be fair to the companies, determining a set of criteria, indicators, and objectives remains challenging. The CSRD directive should serve as a progressive tool, leading us to produce this second research with several recommendations. Our hypothesis is that, given the inability to define a normative ESG framework applicable to all companies across all sectors, it would be advisable to attempt to develop a more individualized approach, tailored to the specificities of each economic entity and the extra-financial issues that concern it. This means developing a “philosophy of extra-financial performance in ED compensation” by promoting a set of principles to guide compensation committees in their choice, evaluation, and measurement of ESG criteria, especially given the favorable context of normative evolution with the CSRD.

Keywords:Executive remuneration; ESG; Non-financial; Remuneration policy; Value sharing; Say on Pay; Environment; Ecology; Climate; Social; Gender equality; Governance; Non-financial performance; Agency theory; CAC40; Diversity and inclusion; CO2 emissions; Corporate governance; Stakeholders; Sustainable value

Introduction

Due to the significant challenges posed by the extra-financial considerations of economic entities, encompassing environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors, the remuneration of executive directors (DMS) has evolved over the past decades, allowing these dimensions to take on greater importance. Because a lack of risk management in these areas could negatively impact companies, potentially leading to a loss of value creation, DMS needed, in accordance with agency theory , to be incentivized to genuinely consider these issues. Hence, the practice of including extra-financial criteria, i.e., ESG, within the remuneration packages of DMS emerged. The integration of ESG criteria in the remuneration of DMS is now firmly established in practice, but the consideration of ESG criteria remains uneven between environmental and social requirements, and almost non-existent for governance. Therefore, these still immature practices are subject to criticism. The Oxfam France report, “Cash 40: Too Many Millions for a Few Men,” highlights, first and foremost, the significant disparities between the remuneration of executives and employees: CEOs of CAC 40 companies earn, on average, 130 times more than their employees. However, it is this data that is of particular interest to our work: only 18% of the remuneration of DMS or “top executives” is based on extra-financial objectives, highlighting a persistent imbalance in the integration of ESG criteria.

ESG Criteria and Remuneration Policies: Now a Given?

An accepted and shared practice

The remuneration of executive directors in large listed companies is composed of three parts: fixed, variable (short/long term), and benefits. While the fixed part and benefits are easily identifiable, the variable part is less so. The fixed part corresponds to an annual guaranteed salary, regardless of the company’s performance. Benefits, often in kind, encompass a variety of provisions typically related to the executive’s role: company car, company apartment, performance shares, retirement plan, non-compete package, etc. The variable part pertains to the executive’s remuneration, expressed as a percentage of the fixed salary, applicable based on the financial and extra-financial performance of the executive, according to certain performance criteria.

A stakeholder demand: The variable portion of executive remuneration is increasingly subject to non-financial objectives linked to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations. Indeed, stakeholders are paying more and more attention to ESG issues (shareholders, institutional investors, regulatory authorities, consumers, employees, trade unions, etc.). There has been a significant trend in recent years towards increased shareholder engagement, particularly from individual shareholders (842 written questions posed at assemblies in 2023, in addition to oral questions), and within this shareholder activism in Europe, the importance accorded to ESG topics is growing.

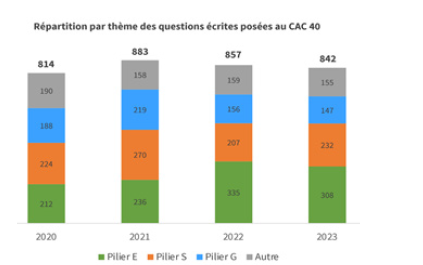

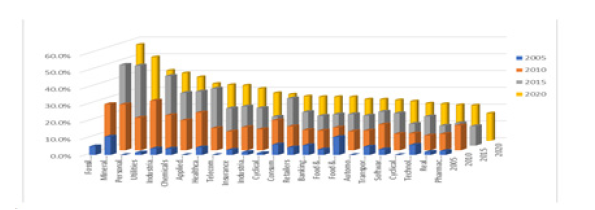

Written questions concerning environmental issues almost doubled between 2020 and 2023. While we do not yet have all the statistics for 2024, it is clear that this trend is continuing. Proportionally, aside from 2021, which was considered exceptional due to the number of written questions following the Covid-19 pandemic, ESG questions have continually taken up an increasingly significant portion of executive inquiries: in 2020, non-ESG written questions represented 23.34% of the total, while in 2022 and 2023, they represented 18.55% and 18.41%, respectively (Figure 1). Companies are expected to incorporate these factors into their operational activities and strategic directions. The integration of ESG criteria in executive remuneration has become a common practice among large European companies. A recent study (2024, Dell’Erba & Ferrarini) conducted on the 300 largest European companies listed on the FTSE Euro First 300 reveals that 61.6% of them consider ESG parameters when defining executive remuneration. For example, 35 companies stated they would adopt these criteria from 2021-2022. The most used ESG criteria include employee diversity and inclusion (cited by 40% of companies), customer satisfaction (25%), CO2 emissions reduction (30%), and commitment to local communities (15%). These initiatives reflect a growing trend to align executive interests with long-term sustainable development goals, thus responding to increased investor and stakeholder demand for more responsible and transparent governance.

Figure 1:Distribution by theme of written questions posed to the CAC 40 since 2020

A requirement now anchored in business practices: As these issues present risks related to the activities of any economic entity, whether in terms of regulation, reputation, litigation, supply, partnership, etc., executives with ESG criteria in their variable remuneration are incentivized to implement a management policy of ESG risks. Similarly, integrating ESG criteria into variable components neutralizes short-term logics that might drive decisions lacking long-term sustainability. By incorporating these non-finan- cial objectives, executives are encouraged to make decisions that consider value creation beyond the current fiscal year. Aligning executive pay with ESG goals also aims to align their interests with stakeholders and the company, consistent with agency theory. Furthermore, this strengthens corporate governance by requiring executives to demonstrate increased accountability and transparency in their actions.

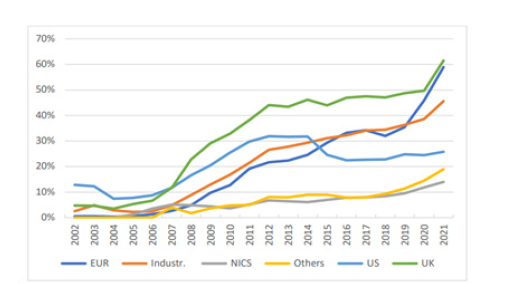

The incentives stemming from these reasons for executives to consider ESG criteria in their variable compensation packages are historically reflected in the growing importance of these criteria over time, across all geographic regions (Figure 2). American and British companies were the first to incorporate ESG criteria into compensation packages, starting in the early 2000s. However, while the consideration of ESG criteria continued to increase in UK executive pay packages during the 2000s and particularly from the 2010s onwards, this trend stabilized in the United States and even decreased by 5%. In Western Europe and other newly industrialized countries (NICs), the inclusion of ESG criteria in executive compensation has grown over time. Nevertheless, it is European companies that have seen the most significant progression, increasing from 10% adoption of some form of “sustainable compensation” in 2009 to around 60% in 2021, while catching up with the UK trend as early as 2019, it is noted that the adoption of NFRD and CSRD directives in 2014 and 2021, respectively, is correlated with an increase in the adoption of ESG criteria in compensation packages.

Figure 2:Evolution of ESG criteria adoption in compensation packages in different geographic zones.

Still nascent implementation

Imbalance between financial and non-financial criteria: In France, the integration of ESG criteria into the compensation policies of listed companies has developed over several years to become indispensable today. Proxy voting guidelines on ESG issues, such as those proposed by As You Sow and Proxy Impact (2024), provide a structured framework for investors wishing to align their votes with principles of environmental, social, and sustainable governance. These guidelines recommend voting against CEOs who hold both chairman and CEO roles, in favour of women on boards, and against anti-ESG resolutions. For example, As You Sow’s “Women on Boards” rule ensures never voting against a female board member. Additionally, these directives advocate for a case-by-case analysis of complex decisions such as mergers and acquisitions. This framework aims to promote sustainable business practices by using shareholder voting power to influence corporate governance decisions. In 2023, As You Sow identified over 150 executive compensation plans that include ESG criteria, marking a 20% increase from the previous year.

Thus, in its latest engagement report from the campaign with

CAC 40 listed companies, FIR welcomed the increasing presence of

E&S criteria in executive remuneration, highlighting a 25% increase

in companies enhancing the E&S component in short or long-term

compensation from the previous year. This raised the number of

companies integrating E&S criteria into long-term remuneration to

35, up from 32 the previous year. Furthermore, among the 12 companies

with the lowest proportions of E&S criteria, typically less

than 20%, just under half (5) indicated they had already initiated

processes to enhance E&S criteria in executive remuneration packages.

It is also encouraging to note that reluctance to increase the

proportion or introduce E&S criteria stems more from operational

considerations than philosophical ones. Indeed, the arguments

commonly cited for a lesser emphasis on ESG criteria are either the

development of a new strategic plan or operational timing considerations.

The argument that the Board deems the current share of

E&S criteria as sufficient would benefit from further analysis, by

comparing the proportion of ESG criteria in compensation packages

with the company’s non-financial performance. According to

PwC , the number of CAC 40 companies integrating CSR criteria into

short-term variable pay rose from 73% in 2017 to 100% in 2022.

In 2024, 43% of employee incentives also include ESG criteria, up

from 18% in 2017. Regarding long-term variable pay, only 10% of

the CAC 40 included ESG criteria, compared to now 88% in 2024.

According to IFA , 88% (+8pts vs 2022) of SBF 120 companies,

totaling 105 companies, integrated at least one climate/environmental

objective into their long-term and/or short-term executive

compensation policies in 2023. When differentiated between short

and long term, 77% have such criteria for short-term compensation

compared to 68% for long-term, respective increases from

2022 of +9 pts and +5 pts. Companies integrating these criteria for

both short and long terms are at 53%, marking a 10-point increase

from 2022. Generally, there is a greater appetite for short-term over

long-term criteria. The CAC 40 appears to outperform the SBF 80,

as in 2022 , 95% of the top 40 listed companies integrated climate/

environmental objectives into the compensation policies for both

short and long terms, compared to 71% of the SBF 80. For shortterm

goals, it was 87% for the CAC 40 versus 58% for the SBF 80,

while for long-term goals, it was 74% for the CAC 40 versus 55% for

the SBF 80. Taking the most ambitious approach of having at least

one climate/environmental criterion for both short and long terms,

63% of CAC 40 companies comply, compared to only 33% of the

SBF 80. The integration of ESG criteria into compensation policies,

while becoming essential and showing real progress, still remains

significantly overshadowed by the weight placed on financial and

personal performance of executives, for two reasons. The first reason

stems from the fact that ESG criteria do not apply to all components

of executive compensation. Examining the segments related

to executive compensation within the Universal Registration Documents

(URD) of CAC 40 listed companies by late 2023 reveals the

average breakdown of compensation packages for Chief Executive

Officers (CEOs) and Managing Directors (MDs) as follows:

A. Fixed salary: 20%.

B. Variable compensation: 28%.

C. Long-term incentive (LT incentive): 48%.

D. Benefits in kind: 4%.

The potential integration of ESG criteria into the overall performance assessment of executives covers an average of 75% of their compensation, with the remaining 25% being guaranteed. This distribution may vary based on the CEO or MD status, as MDs typically have a fixed salary component averaging 10 percentage points higher than CEOs (24% vs. 14%), and their benefits in kind are on average twice as high in value. The second reason revolves around the predominance of financial criteria over non-financial criteria in terms of weighting within performance objectives linked to ESG criteria. Thus, whether in long-term compensation or annual bonuses, financial metrics overwhelmingly dominate the criteria used to evaluate executive performance (Figure 3), despite the increasing share dedicated to CSR criteria in recent years (between 10% and 20% in 2017 vs. between 20% and 30% in 2024, PwC). As highlighted by FIR, companies still tend to prioritize financial metrics in determining corporate performance. Hence, none of the CAC 40 companies have predominantly tied executive compensation to environmental and social criteria to date. It is worth noting the efforts of Veolia, however, which reports a parity between the financial and non-financial criteria, with 50% of E&S criteria in the CEO’s long-term compensation policy . For example, in terms of the lesser consideration given to ESG criteria, the “climate/environment” criterion, one of the most commonly used ESG criteria in variable compensation policies for executives in the SBF 120, on average represents 11.3% of long-term compensation, an increase of 1.4 percentage points from 2022. Meanwhile, it represents 6.3% of short-term variable compensation, up by 0.7 percentage points. This indicates that the “climate/environment” criterion is more valued in long-term compensation than in short-term compensation. However, the trend appears to be reversed when looking at other non-financial criteria. Overall, non-financial criteria account for an average of 8.9% in long-term compensation, while they reach 28.9% in short-term compensation. Nevertheless, financial criteria remain predominant, comprising 79.8% of long-term variable compensation and 64.8% for short-term.

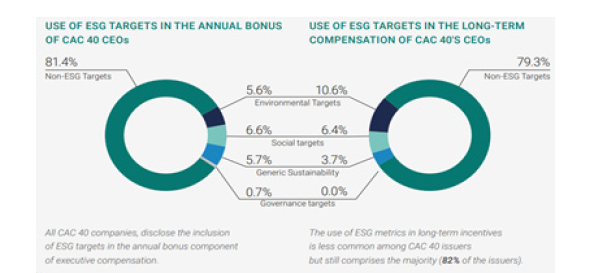

Figure 3:Distribution of performance objectives for annual bonuses and long-term incentives within the CAC 40.

What about goal achievement?

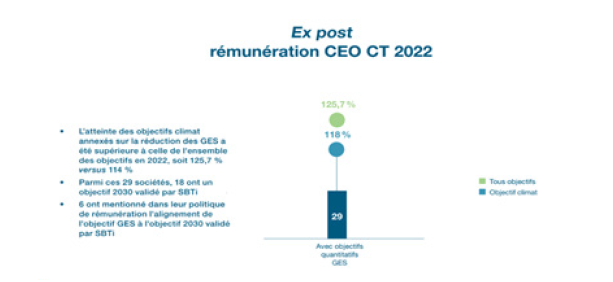

Indeed, the inclusion of ESG criteria in compensation packages primarily aims to incentivize executives, and one can reasonably question the effectiveness of this non-financial weighting. If the effectiveness of incentivizing executives towards achieving ESG goals is reduced, then we might observe genuine non-financial performance, particularly in environmental issues. Thus, across all SBF 120 companies, the average achievement of all ex post short-term variable compensation objectives for executives reached 110.3% in 2022, while the average achievement of “climate/environment” objectives is 113%, with a particularly strong performance in criteria related to greenhouse gas emissions reduction at 125.7% (Figure 4). The increasing emphasis on ESG issues shows no signs of slowing down, as the integration of ESG criteria in compensation packages is evolving to include other company actors beyond executive directors. According to PwC, 67% of CAC 40 companies are gradually incorporating CSR criteria into the short-term variable compensation of other company actors. Company practices are starting to align between executives and other actors such as senior executives, top management managers, etc. In line with this approach, FIR included a sub-question in Question 4 of its campaign addressing CAC 40 listed companies, concerning the integration of E&S criteria in employee compensation – excluding executives .

Figure 4:Achievement of climate and greenhouse gas reduction objectives in the ex post short-term compensation of executives in 2022.

According to FIR, although all companies claim to include E&S criteria in employee compensation policies, only seven companies offer E&S criteria in bonuses, long-term compensation, and profit sharing. Meanwhile, 14 companies still do not include these criteria in long-term compensation and 11 do not include them in bonus compensation. Among the 29 companies that include criteria in employees’ short-term compensation, only 19 provide details on the share of these criteria. Similarly, among the 26 companies that offer long-term criteria, 24 have detailed the share of these criteria. Regarding bonus compensation, Danone stands out, offering a share of 30% to 50% for E&S criteria depending on the employee’s hierarchical level. Additionally, the share of E&S criteria in the bonus compensation for executives at Crédit Agricole, Kering, and Veolia is 30%. Twenty-one issuers also integrate environmental and/or social criteria into profit-sharing agreements, down from 24 companies in 2021. This decline is likely due to the 2021 question regarding the integration of E&S criteria being limited to profit-sharing agreements. However, this evolution is not without challenges. As FIR explains, the responses provided tend to focus more on the integration of environmental and social criteria in the compensation policies of executive employees rather than that of regular employees, making it difficult to draw conclusive analyses of employee compensation policies and their defining processes. The heterogeneity of the data provided, particularly regarding the number of employees affected by these criteria in their compensation, prevents a qualitative analysis of this subject. Twenty-six companies have indeed provided the number of employees concerned with E&S criteria in their compensation, but it remains unclear whether these numbers include executives or social representatives and without sufficient context on what this represents relative to the total workforce. Nonetheless, Michelin and Saint-Gobain are noted as top performers by communicating the proportion of employees affected by E&S criteria in bonus and long-term compensation, representing a significant portion of their workforce (80% and 65% of the workforce, respectively). Thus, FIR writes that “the topic of non-financial criteria included in employee compensation policies still does not seem to be fully mastered by companies.”

Challenges of Integrating ESG Issues into Compensation Policies

Unequal consideration between E, S, and G criteria

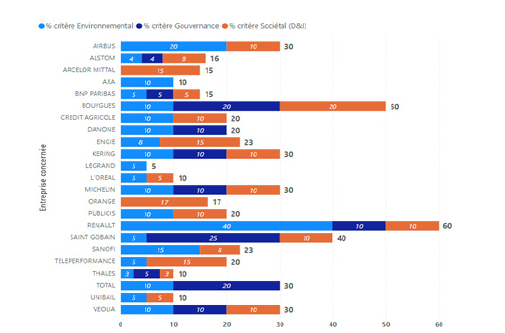

Publicly listed companies have largely introduced ESG criteria into executive compensation, with an average weighting ranging from 10% to 60% (Figure 5), at different organizational levels. However, it is difficult to have a clear view because, in addition to the varying importance of ESG criteria among companies, these criteria do not have the same weightings among themselves. There are no uniform practices, neither by index nor by industry sector. Moreover, two inequalities of treatment are noteworthy: one between E, S, and G criteria, and another within each of these categories. The work of the ESSEC Women Board Ready, whose analyses are presented in the Annexes of this document, has confirmed these two inequalities of treatment. The first inequality in the consideration of ESG criteria lies primarily between the categories themselves. Indeed, there is particular attention paid to Environmental (E) criteria, followed by Social (S) criteria, with a near-absence of consideration for Governance (G) criteria. This is evident in the short-term variable compensation (Figure 6), where the average share of ESG criteria is 19.6%. Among the 23 companies with a detailed breakdown of ESG criteria, there are significant disparities: 21 companies have at least one environmental criterion, while only 9 have deployed criteria across all three categories E, S, and G . This is similarly observed in long-term variable compensation (Figure 7), where the average share of ESG criteria is 19.8%. Among the 23 companies with a detailed breakdown of ESG criteria, there are significant disparities: only 16 companies have at least one environmental criterion, while only 11 have deployed criteria in both the E and S categories. Notably, Veolia is the only company that includes criteria in all three categories-E, S, and G-in their long-term variable compensation . When revisiting the weighted distribution of ESG criteria in remuneration (Figure 3), the same observation emerges, namely the difference in consideration between the criteria: the environment represents 5.6% of the annual bonus of CAC 40 executives, compared to 6.6% for social criteria, 5.7% for so-called “generic” criteria, and only 0.7% for governance criteria. Conversely, for long-term remuneration, the environment accounts for 10.6% of the objectives, compared to 6.4% for social objectives, 3.7% for generic criteria, and 0% for governance.

Figure 5:Proportions of ESG criteria in short- and long-term compensation of CAC 40 companies in 2023.

Figure 6:Proportions of ESG criteria in terms of E, S, and G categories in short-term variable compensation of CAC 40 executives.

Figure 7:Proportions of ESG criteria in terms of E, S, and G categories in long-term variable compensation of CAC 40 executives.

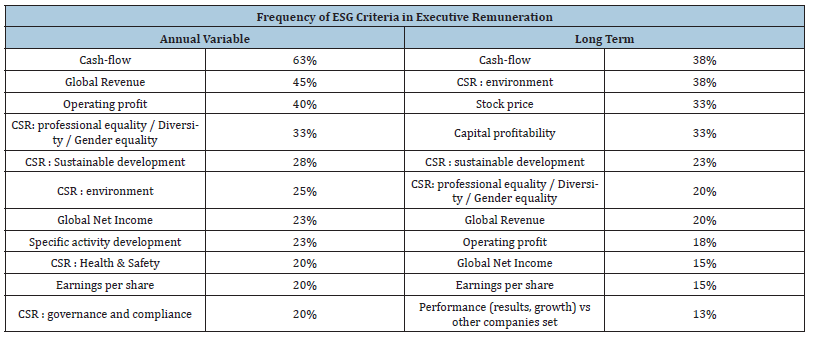

A plurality of ESG criteria still too discretionary

The inequality of treatment does not only concern the E, S, and G categories but also the criteria within each category. As PwC pointed out, the most recurrent criteria are primarily CO2 emissions and D&I (Diversity & Inclusion). However, mechanisms increasingly tend to integrate more varied indicators to achieve the company’s strategy and CSR priorities. According to Morrow Sodali, the most used environmental criterion is greenhouse gas emissions targets, followed by elements related to agricultural regeneration linked to companies’ supply chains, as well as land protection and the development of the circular economy. In societal matters, the most common targets are gender diversity and workplace accidents, particularly in the industrial sector. This is followed by employee engagement levels and the number of people with disabilities. Finally, there are also some metrics specific to companies’ sectoral activities, such as territorial anchoring, for example. One can therefore assume that the unequal weighting between all the criteria leads to arbitration effects by executives, favoring the criteria for which they are most judged, thus creating a hierarchy among the ESG criteria. The hierarchy in the importance of the criteria, pushing executives to act mainly on certain criteria over others, thus produces different performances depending on the criteria, that is, different rates of achieving objectives, whose standard deviation can sometimes vary widely (Figure 8). Thus, if we focus on the rate of achieving environmental objectives, compared to the rate of achieving other extra-financial criteria, we notice an overperformance on climate objectives, particularly greenhouse gas emissions, to the detriment of other criteria. Furthermore, the overperformance is more pronounced for the quantitative elements related to greenhouse gas emissions, compared to other climate criteria (Figure 8).

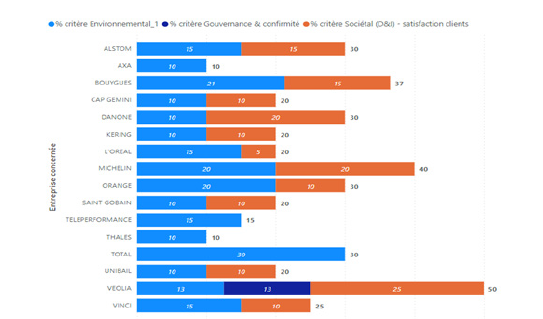

Figure 8:Achievement rate of climate/environmental objectives vs. Achievement rate of all objectives.

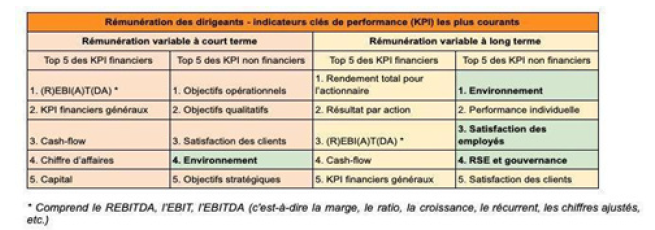

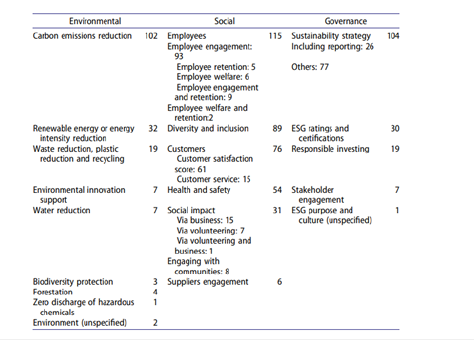

Thus, it is important to note that the diversity of ESG criteria weightings and the consequently unequal importance given to non-financial issues contribute to the complexity of linking ESG concerns with the remuneration of executive directors. Furthermore, this complexity is exacerbated when addressing the definition of specific metrics, monitoring their achievement, and their relevance in relation to the company’s issues. This raises the question of how to define and measure non-financial objectives, targets, and performance in the evaluation of executive remuneration packages. The unequal consideration given to ESG issues, both between categories and within each category, creates competition among criteria. Specifically, when it becomes more advantageous, given a company’s non-financial performance, to select one criterion over another in determining the executive director’s performance and therefore their remuneration package, certain criteria are highlighted. For instance, criteria deemed more advantageous-either due to a lack of rigor in performance determination, such as an “environmental” criterion, or because they align with shareholder wealth creation interests, like the cash flow criterion-are therefore given greater prominence and show higher frequency in remuneration packages (Table 1). In other words, the diversity and competition among criteria lead to “discretionary and self-interested” effects. Moreover, some so-called “generic” criteria lack transparency regarding their parameters, targets, and respective weightings in the metrics. According to PwC, as previously mentioned, ESG rating objectives tend to be replaced by performance indicators on which executives and employees have more flexibility to act . As observed in Table 1, the preferred performance indicators remain financial, with a predominant focus on cash flow, both for annual variable remuneration (63% occurrence) and for long-term remuneration (38%). More specifically, the most frequent criteria for determining variable remuneration are financial, including cash flow, global revenue (45%), and operating result (40%). For long-term remuneration, financial criteria also hold greater importance, with cash flow, stock price (33%), and capital profitability (33%) being notable. It is worth noting, however, that the criterion “ESG: Environment” holds a significant position, appearing in 38% of long-term remuneration cases, equal to cash flow. Overall, there is a growing trend towards incorporating extra-financial criteria, particularly environmental ones. The differences in frequency among criteria can be attributed to the discretionary selection made by companies in determining the performance indicators used for executive remuneration [1-14]. According to the frequencies presented in Table 1, the average number of indicators used for determining the variable portion is 6.15, and for long-term remuneration, 3.6 indicators. This trend is confirmed by recent academic studies, which conclude that there is “no standardized approach to performance evaluation” in ESG-based remuneration. The absence of a standardized approach can be problematic for both the legitimacy of the remuneration received by executives and its objectivity.

Table 1:Frequency of ESG criteria in the remuneration of executive directors in the SBF 120.

Regarding the legitimacy of the remuneration, in practice, there are cases where ESG-based remuneration is used by administrative bodies as a tactic to control executive management or as a defense of private interests by the management, rather than promoting the company’s sustainability. This results in a “decoupling” between ESG achievement and ESG remuneration. For example , a low stock performance per share is associated with a higher likelihood of adopting an ESG-based remuneration policy. One hypothesis by the authors to explain this correlation is that lower stock performance may lead executives to offset their reduced stock gains with additional variable remuneration based on ESG criteria, which are supposedly controllable, regardless of the actual extra-financial performance of the executive or the company . Regarding the objectivity of ESG remuneration, it is observed that, as illustrated in Figure 9, based on a sample of listed companies in the UK, remuneration committees tend to “adopt self-designed evaluation methods and metrics, over which they exercise substantial discretion . A distinction is observed between objective metric evaluations-such as reductions in carbon emissions or ESG ratings and certifications-and more subjective evaluations, such as sustainable strategy or social impact.

Figure 9:Application of discretionary logic to major ESG indicators.

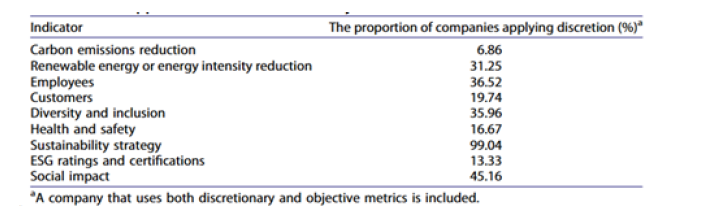

An “objective evaluation metric” refers to a metric for which the remuneration committee applies little to no subjective judgment. The evaluation of sustainable strategy is a specific case, as all companies deploy ESG-related metrics based on the company’s specifics and processes that are unique and non-quantifiable. Generally, most companies in the studied panel prefer metrics with objective evaluations, although subjective and objective approaches are sometimes closely linked. For example, customer satisfaction can be assessed either through internal, company-specific, and therefore subjective mechanisms, or through indices from third-party organizations, which are objective. While the study acknowledges that metrics evaluated subjectively can be more easily manipulated by the remuneration committee, it also nuances this conclusion. The analysis concludes that objective metrics are not necessarily more effective or immune to manipulation. When a company creates internal objective metrics or selectively chooses from numerous third-party metrics, these metrics can be dysfunctional. The study also identified several issues within its panel related to evaluation methods and the performance of certain metrics that could alter the incentive effects of ESG-based remuneration. In other words, objective evaluation of metrics is not necessarily a guarantee of impartiality in choosing ESG criteria, nor of the absence of interests focused on maximizing remuneration when selecting these criteria. It remains challenging to establish a balance in creating a corpus of extra-financial performance indicators for evaluating the performance of executives within their remuneration packages. While there is a growing trend towards incorporating ESG parameters into executive remuneration, questions of impartiality in defining criteria, indicators, and metrics persist. This trend is generally observed across Europe. For example, discretionary determination of ESG criteria used in remuneration packages is noted in Belgium and Luxembourg (Figure 10). Based on data provided by the Diligent Institute regarding 55 listed companies in these two countries, PwC Belgium has identified similar observations concerning the choice of ESG criteria in both short-term and long-term variable remuneration. For instance, there is an increasing number of shareholder proposals requesting companies to incorporate ESG goals into executive remuneration plans, with the most frequently used indicators being social (S) metrics-especially concerning health and safety-although their weighting is lower compared to environmental (E) criteria. Ultimately, it is observed that executive remuneration still largely relies on performance measures based on financial criteria .

Figure 10:Executive remuneration – most common key performance indicators (KPIs).

Moreover, even if it were possible to counteract the windfall effects caused by the discretionary choice of ESG criteria by establishing a set of ESG criteria tailored to each company based on its specifics and sector, the issue of objectively and quantifiably measuring performance would still persist. Indeed, even assuming that non-financial ratings are the most credible measure of non-financial performance, one can only observe the variety of these ratings for the same company, sometimes resulting in very uneven performance outcomes. This was noted by the researchers from MIT’s Aggregate Confusion , who analyzed the divergence in ESG ratings across several companies and concluded that there is a “divergence” between ratings for given company performances, particularly in the categories of “Climate Risk Management,” “Product Safety,” “Corporate Governance,” “Corruption,” and “Environmental Management System,” affecting E, S, and G alike. The authors also conclude that the divergence is particularly pronounced for KLD data, which is the data most commonly used in current academic research on ESG. They identify three solutions: (i) include different ESG ratings for the same company in the analysis to measure a “consensual ESG performance” as perceived by the markets; (ii) use a specific ESG rating that characterizes a particular company, while clearly explaining why this rating method is more suitable for a specific study; (iii) develop hypotheses around more specific ESG performance subcategories, such as greenhouse gas emissions or labor practices, which would help avoid divergence in scope and weighting, though it would still support a risk of measurement divergence. Regardless of the proposed solution, the authors emphasize the importance of examining the data, highlighting the need for transparency in data generation and creation procedures. To improve practices, we propose specific recommendations, such as adopting sector-specific approaches for ESG criteria, developing robust methodologies for measuring non-financial performance, and promoting transparent communication about the results achieved.

Some Recommendations on ESG Criteria to Prioritize in the Executive Directors’ Compensation Policy

Towards a renewed philosophy of extra-financial performance in ED compensation

To renew the philosophy of extra-financial performance in ED compensation, it is essential to identify why ESG criteria are crucial to the company because they are beneficial in terms of value creation. It is also important to determine the extent to which ESG criteria should be imposed through regulatory soft law and how a company can, with full legitimacy and justification, select the ESG criteria that objectively apply to it.

Approaching ESG criteria in ED compensation as vectors of value creation

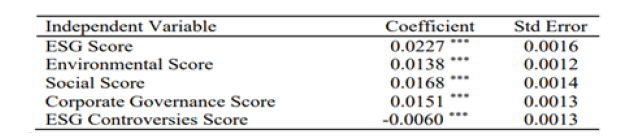

While the integration of ESG criteria in compensation packages has become entrenched in practices, it remains too discretionary and potentially instituted with a single objective: to voluntarily or involuntarily increase ED compensation, potentially decoupled from actual performance-especially extra-financial performance. Given this challenge of legitimizing ED compensation policy, ESG criteria can be justified when placed in the context of their deployment. Indeed, if extra-financial performance is considered to contribute to a company’s value creation, then incorporating ESG criteria into the compensation policy becomes as legitimate an objective as conventional financial criteria. In other words, ED are incentivized to achieve extra-financial performance for reasons other than increasing their compensation or some “moral conformity” on these issues. Pursuing ESG performance becomes a natural goal of ED performance. This perspective, consisting of a change in the view of the ideal performance of a ED, thus calls for considering ESG criteria in ED compensation as vectors of value creation. This val- ue is understood in a broader sense than that usually attributed to the financial performance resulting from the actions of an ED. This new perspective can find some justification in recent academic research. By analyzing the following multiple regression (Figure 11), we observe a positive and highly significant correlation between the explanatory variable “ESG Score” and the dependent variable “Adoption of Pay for Sustainable Performance.” In other words, this correlation shows that among the 8649 listed companies in a sample spread across 58 countries, those that adopted a ED compensation policy based partly on ESG criteria had a better ESG profile beforehand than those that did not adopt such an ESG policy. Put differently, compensation based on ESG criteria stems from prior efforts to achieve extra-financial performance, indicating a new perspective where ESG performance is considered as important as more conventional financial performance .

Figure 11:ESG scores and adoption of pay for sustainable performance.

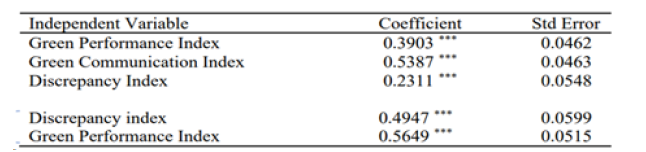

Nevertheless, the indexing of ED remuneration to non-financial performance does not indicate the contribution of ED remuneration based on ESG criteria to overall non-financial performance. Can we then establish a correlation between the adoption of a remuneration policy based on ESG criteria and the non-financial performance of the company? In other words, can we confirm the effectiveness of the incentive represented by the inclusion of ESG criteria in ED remuneration? Indeed, it appears that environmental performance (“Green Performance”) is positively correlated with the adoption of ESG criteria within remuneration policies, as is the communication of the company’s non-financial results (Figure 12). The outcome of this study supports the notion that “linking ESG criteria with remuneration is not an end in itself, but rather requires a simultaneous change within the organisation, as well as the emergence of a business culture largely oriented towards ethics.”

Figure 12:Environmental performance, communication, and adoption of esg remuneration policies.

Box 1 – A new philosophy of “value creation” for genuine nonfinancial performance criteria and indicators influencing ed remuneration

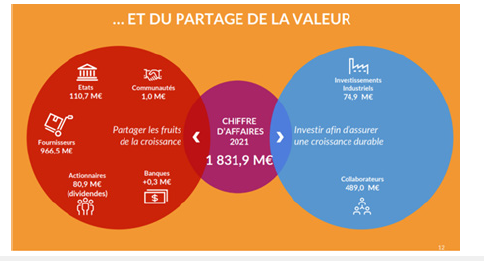

Reflecting on the inclusion of ESG criteria within ED remuneration packages necessitates a complementary reflection on the meaning of “value creation.” This box aims to outline a preliminary concept. In recent years, the topic of “value sharing” has been frequently discussed, driven by an economic downturn and increased visibility of income and wealth inequalities. The culmination of these debates was the adoption, in August 2022, of legislation aimed at improving purchasing power protection in France. Among the key measures of the law was the transformation of the exceptional purchasing power bonus (“Macron bonus”) into a “value- sharing bonus (PPV).” At the employer’s discretion, this bonus supplements wages up to a maximum of €3,000 per calendar year, exempt from all employee and employer contributions . This provision highlighted the themes of value creation and sharing, leaving it up to companies to address them. However, no universally accepted definition has emerged, and economic actors generally refer to their own non-financial commitments to address this new issue.

The question now is to what extent value sharing can be clearly understood and properly implemented for the benefit of all stakeholders. The idea of “sharing a value” produced by a company is initially confined to accounting and financial considerations. Thus, even if there is no definitive consensus definition of “value sharing,” it can be summarized as “a fair and optimal distribution of wealth among the various stakeholders of the company to enhance economic efficiency – strengthening the competitiveness of companies and boosting sustainable growth – and to foster social progress – creating quality jobs and increasing purchasing power.” Value sharing is thus considered as the distribution of “added value,” meaning the fruits of economic production to be shared between labor – the employees – and capital – the shareholder owners. However, reducing the value produced by a company to a few figures in a financial statement seems narrow and outdated given the significant roles economic actors play in all dimensions of collective life: social, political, cultural, etc. This is why several business observers have opposed a purely financial conception of value.

Indeed, a purely economic definition of value – as the assessment of a good or service based on the amount of labor required for its production in a market where supply and demand meet – is insufficient to address the non-financial dimensions of a company, which are recognized as sources of non-financial performance with future financial opportunities. Reflecting on value sharing cannot ignore a broad conception of “value,” placing it within an ecosystem nourished by the company’s stakeholders. However, while financial value is well established by accounting, “non-financial value” is still open to interpretation, which is complex given the plurality of non-financial dimensions of a company: social, innovation, supply chain, philanthropy, etc. By maintaining a dual conception of both financial and non-financial value, it is possible to develop a typology of “value sharing” to provide some definitional elements. By adopting a financial and non-financial approach to the notion of “value,” the ICR has determined a typological definition, i.e., identifying the various meanings that can be attributed to the expression “value sharing,” to facilitate setting the issues. Indeed, only a clear definition will allow economic actors to grasp the issues of this subject and commit their resources- financial, human, etc. – to address it with a certain degree of engagement and thus performance. Without aiming for exhaustiveness, three definitions can be identified. The first is a weak restrictive definition: “Value sharing corresponds to the distribution of a company’s revenue among all its stakeholder contributors to the production of that value.” For example:

The second is a strong restrictive definition: “Value sharing corresponds to the distribution of financial value based on a financial indicator (revenue, net income, free cash flow, etc.) while considering non-financial considerations.” For example:

The third is an extensive definition: “Value sharing corresponds to the distribution of financial and non-financial value based on financial and non-financial indicators (revenue, net income, free cash flow, etc., and CO2 equivalent emissions, equity ratio, occurrence of psychosocial risks, etc.) for the benefit of all stakeholders in an economic actor’s ecosystem.” For example:

Since the weak restrictive definition is purely “accounting,” it is not favored. The strong restrictive definition is interesting as it legitimizes practices such as philanthropy or donations to charitable organizations. However, it lacks a fully non-financial conception of “value” and the role of “civic actors” that double materiality has granted to economic actors. The extensive definition marks a higher degree of commitment, as it addresses the notion of value in an irreversibly dual sense (financial and non-financial) and considers the distribution of created value as a strategic development tool for the company towards both financial and non-financial performance. This last definition is the most ambitious and thus the most desirable (Figure 13-15). We have identified seven financial indicators that can lead to positive non-financial consequences in terms of value sharing and can be more or less easily implemented (difficulty level). The following table summarizes them. Since the notion of value cannot be reduced to using financial indicators, even for non-financial purposes, it is preferable to develop non-financial indicators, detached from financial logic, to better conform to the extensive definition of value sharing.

Figure 13:

Figure 14:

Figure 15:

Afep-Medef code: Towards an ambitious non-financial principles framework for ED remuneration

The inclusion of ESG criteria in remuneration packages is beneficial for a company’s overall performance. The question then arises about how this inclusion is implemented. As noted earlier, the selection and weighting of criteria remain too discretionary, despite the growing prevalence of this practice. Thus, it is essential to analyse how the recommendations outlined by the French Association of Private Enterprises (Afep) and the French Business Confederation (Medef), together within the Afep-Medef code, regulate the non-financial framework for ED remuneration. Specifically, it is necessary to assess the ambition of the code and any potential modifications that could enhance the promotion and effectiveness of incorporating ESG criteria into remuneration packages. In other words, considering the ESG issues highlighted thus far in relation to remuneration packages, is it pertinent to propose changes to the code?

The governance body within a company responsible for “studying and proposing all elements of remuneration and benefits for executive directors” is the remuneration committee. Subsequently, the board of directors “debates the performance of executive directors, excluding the interested parties,” since determining remuneration packages “falls under the responsibility of the board of directors,” which must “justify its decisions in this matter.” The board then determines, based on the committee’s proposal, remuneration that must be “competitive, aligned with the company’s strategy and context, and aimed at promoting the company’s performance and competitiveness in the medium and long term.” Thus, ED remuneration is situated within a market context – hence the requirement for competitiveness – and a sector context – hence the importance of strategy and performance promotion. While performance and competitiveness are mentioned for both the short and medium term, there is no explicit reference to responsibility or sustainability. The code specifies that these competitiveness and performance objectives must be achieved by “integrating several criteria related to social and environmental responsibility, including at least one criterion linked to the company’s climate objectives.” Thus, the code’s requirement for long-term competitiveness and performance is immediately restricted to a minimal environmental criterion, overlooking any notion of non-financial performance as a stakeholder in the company’s strategy. This minimal requirement reflects our earlier observation of an over-representation of environmental and then social criteria, with a near absence of governance criteria. However, a company’s non-financial performance can only be assessed at a global level and cannot be reduced to a single category of criterion.

Moreover, these criteria must be “precisely defined,” “reflect the most significant social and environmental issues for the company,” and, if possible, “quantifiable.” Therefore, there is a threefold nuance in the requirement: the criterion definition must be precise but not necessarily technical or objective, the criterion must reflect issues deemed important for the company and not necessarily for society at large as a more holistic view of value sharing might suggest, and finally, “quantifiable criteria should be preferred,” though there is no obligation for such quantification. In other words, according to the Afep-Medef code, ED remuneration must include ESG criteria without specifying the number or proportion of such criteria, and these criteria need not be technical, holistic, or quantifiable, which directly raises the issue of measurability, as highlighted by Dell’Erba and Ferrarini: “these metrics and targets frequently rely on vague and general indicators, making quantification challenging” (p.32). There is also no mention of prohibiting the ex post definition of criteria.

To implement this ED remuneration policy, the board and the remuneration committee must adhere to a number of remuneration determination principles, totaling six. First, the remuneration policy must be “comprehensive,” meaning it should encompass all remuneration elements in a global assessment. This first principle is thus, in its global assessment, favorable to a non-financial approach to remuneration. Second, it must be “balanced” among the various remuneration elements, implying a justification for each criterion and alignment with the company’s social interest. It is notable that a company is “managed in its social interest, considering the social and environmental issues of its activity. Next, a principle of “comparability” applies, which means remuneration must be assessed contextually, considering the profession, market, responsibilities assumed, results achieved, work performed, the company’s state (e.g., turnaround), etc. The fourth principle is “consistency,” requiring remuneration to be determined in relation to other executives and employees through equity ratios. Fifth, the code advocates for “clarity of rules,” promoting “simple, stable, and transparent” rules. Performance criteria should align with the company’s objectives while being demanding, explicit, and sustainable. Finally, the last principle is “measurement,” deriving a fair balance between the company’s social interest, market practices, executive performance, and stakeholders. These principles can be categorized into two groups: internal principles (comprehensiveness, balance, consistency, clarity) which relate ED remuneration to the company’s internal environment, such as combating abuse of trust (through the principle of comprehensiveness) or remuneration in relation to employees (through the principle of consistency); and external principles (comparability and measurement), which place ED remuneration in the context of society, including economic structures (market, sector, competitors, etc.) and social structures (adequate consideration of stakeholders). It is evident that the second category, which relates ED remuneration to society, would benefit from further development, especially considering the recent emphasis on the “double materiality” concept, which requires ongoing interaction between the economic entity and its own environment, both close (scopes 1 and 2) and distant (scope 3). Therefore, it would be advisable to consider establishing a new remuneration determination principle that accounts for this new evolution in the company’s relationship with its environment. This new “responsibility” principle would extend from the “measurement” principle to highlight the importance of ESG criteria, potentially including a “clawback” clause, meaning the return of remuneration elements if non-financial results are restated, indicators are revised, or severe misconduct occurs. The remuneration component most concerned with these requirements is the annual variable remuneration, which is likely the most affected by the inclusion of ESG criteria. Keeping in mind the observed tendency to define ESG criteria discretionarily based on ED interests, it is possible to evolve the code’s requirements to strengthen the role of ESG criteria in the actual assessment of ED performance and, consequently, in the determination of their remuneration policy. It is also noteworthy that the code provides for “exceptional circumstances” in long-term ED remuner- ation, which may justify modifications to performance conditions during a period. Among the cited reasons are substantial changes in scope, unexpected competitive context changes, or the loss of relevance of a benchmark or comparison group. No specific non-financial conditions are mentioned.

In conclusion, amending the Afep-Medef code would represent a significant step towards greater incorporation of ESG criteria in ED remuneration packages. Given that these criteria are beneficial to the company, enforcing them through the reference code for listed companies would be legitimate. However, like any soft law framework, the code remains subject to debate and finds its effectiveness in its implementation rather than its structure. Thus, the importance of raising awareness among the board of directors about ESG issues cannot be completely disregarded if a true remuneration policy based on genuine non-financial performance of EDs is to be realized. In this spirit, R. Barontini and J.G. Hill, in the aforementioned study , conclude that increasing the independence and diversity rates within a board of directors enhances support for remuneration policies based on ESG practices. In other words, the composition of the board has direct effects on its sensitivity to ESG issues.

Sectorialise, measure, and communicate: An effective triptych for justifying ED remuneration based on ESG criteria?

While incorporating ESG criteria into ED remuneration policies is beneficial for the company and can be guided by the Afep-Medef code’s soft law approach, the challenge of determining which ESG criteria should be used for a company, given its sectoral and market contexts, persists. As discussed earlier, it is challenging to establish a non-discretionary and impartial set of ESG criteria and indicators to support the determination of EDs’ non-financial performance in remuneration policies. These conclusions are similar to those of Dell’Erba & Ferrarini (2024), whose data “suggest a lack of clear patterns emerging from corporate practice, highlighting the need for consolidation in this context. Few metrics are clearly measurable, and there is a general lack of appropriate metrics and targets.” (p.39)

Furthermore, while the principles outlined in the Afep-Medef code are not without merit, they lack both the coercion and ambition required to translate ESG criteria into genuine overall company performance. Rather than merely selecting a list of criteria or applying principles, the focus should be on developing a “search for non-financial performance” approach, which can be executed in three phases: (i) Sectorialise the non-financial approach by determining ESG criteria suited to the socio-economic realities of the company (markets, competitors, society, stakeholders, etc.); (ii) Emphasize both quantitative and qualitative measurement of indicators resulting from these criteria using specific methodologies and metrics; (iii) Communicate the results to justify remuneration and invite stakeholders informed about these issues to contribute through discrete verification.

Sectorialise: Sectorialising ESG criteria used to define ED performance and thus their remuneration is crucial for legitimizing the remuneration based on these ESG criteria. An ESG criterion that is not applicable to a company due to its specific sector could easily be deemed satisfied, triggering remuneration even if it does not correspond to any particular performance. For example, the payment of remuneration based on water consumption criteria for the advertising and media sector could seem questionable. Choosing criteria for executive remuneration and aligning these criteria with the company’s real non-financial challenges is essential for responsible and sustainable management. Moreover, not all sectors have the same impacts on their environments and stakeholders. The extent to which ESG criteria are incorporated into ED remuneration policies can be influenced by sector-specific characteristics. For instance, companies with significant environmental impacts, such as those in fossil fuels, mining, or heavy manufacturing, have seen a notable increase in the adoption of ESG-based remuneration policies in recent years. This reflects an increasing alignment of remuneration practices with sector-specific environmental performance requirements, as illustrated in Figure 16.

Figure 16:ESG indicators in executive remuneration.

Sectorialisation involves tailoring ESG criteria to the unique socio-

economic and environmental realities of the company’s sector.

This means:

1. Identifying Relevant ESG Issues: Understanding which

ESG issues are most pertinent to the company’s sector and operations.

For instance, sectors with high carbon emissions may

focus on climate-related metrics, while sectors with substantial

labor forces may prioritize social issues like employee welfare

and diversity.

2. Ensuring Applicability and Relevance: Selecting criteria

that are both applicable and impactful for the specific sector.

For example, an ESG criterion related to water usage might be

crucial for industries like agriculture or textiles, but less relevant

for software or consulting firms.

3. Aligning with Industry Standards and Expectations: Ensuring

that the chosen criteria align with industry norms and

stakeholder expectations. This involves keeping abreast of sectoral

ESG reporting standards and benchmarks and integrating

them into the remuneration framework.

Example: A mining company might adopt ESG criteria focused on reducing environmental degradation, improving community relations, and enhancing safety standards, while a technology firm might emphasize data privacy, energy efficiency, and workforce diversity. By sectorialising the approach, companies can ensure that their ESG criteria are meaningful, measurable, and truly reflective of their operational impacts and stakeholder concerns. This alignment is key to justifying the remuneration based on ESG performance and fostering greater accountability and transparency in executive pay practices .

Sectorialisation also helps avoid discretionary and self-serving determination of ESG criteria by utilizing the concept of “materiality.” Materiality is understood as “what can have a significant impact on a company, its activities, and its ability to create financial and extra-financial value for itself and its stakeholders.” Therefore, sectorialisation of ESG criteria in the remuneration package ensures that remuneration is linked to the company’s extra-financial performance. This is why the FIR chose in its latest campaign to ask CAC 40 companies to “specify how the E&S criteria integrated into the variable remuneration policies (short and long term, if applicable) [for executives] reflect the most material E&S issues the company is facing.” It concludes that aligning extra-financial criteria with the material issues of companies is neither widespread nor straightforward. Indeed, while most companies claim to align their criteria with materiality, the level of explanation and detail is limited, making it difficult to link materiality with evaluation criteria. Out of the 40 index companies, only 6 provided detailed information, thoroughly describing the criteria selection and its connection to ESG issues, strategies, and stakeholders.

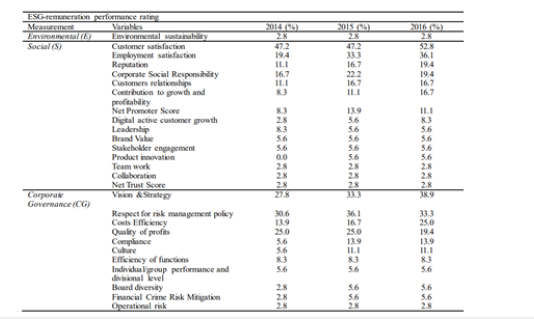

Thus, sectorialisation is a key factor in justifying the ESG criteria used to legitimate the payment of remuneration based on extra- financial performance. However, selecting sector-specific ESG criteria is not straightforward and can be challenging to implement. In other words, identifying ESG criteria that accurately reflect the materiality of a company’s extra-financial issues can be complex. A first solution to this problem would be for a company to choose the most commonly used ESG criteria among its peers, that is, companies with which it shares certain characteristics: size, market, revenue, supply chains, stock index, etc., and of course, sector of activity. Such a selection would ensure a minimum level of objectivity in criterion choice, provided there is no collusion with the peers in question. For instance, Deloitte identifies among industrial companies the most commonly used ESG criteria as those related to health and safety (S) and carbon footprint (E), while service companies focus more on criteria related to human capital, such as diversity and inclusion, or external ESG ratings . A second, less convincing solution, but preferable to not considering ESG criteria at all, would be to select the most common criteria or those most widely recognized as likely to align with the materiality of any economic activity. For example, the carbon footprint is a criterion that any economic entity can calculate due to the comprehensive approach of scopes 1, 2, and 3. This is reflected in the predominance of certain criteria within the FTSE 350, such as carbon footprint reduction (a criterion present in the remuneration policies of 102 FTSE 350 companies), employee engagement, and the company’s sustainability strategy (Figure 17).

Figure 17:ESG indicators in executive compensation within the FTSE 350.

Moreover, while selecting sector-specific ESG criteria can be challenging, linking these criteria to the company’s performance can be even more arduous. However, this requirement to connect remuneration with performance is a historical demand of shareholder advisory agencies (proxies). With the rise of extra-financial performance-based remuneration, proxies view the choice of ESG criteria as essential. As they regularly emphasize, “there must be a clear link between the company’s performance and the incentives of variable remuneration. Financial and extra-financial conditions, including ESG criteria, are relevant as long as they reward effective performance in line with the company’s purpose, strategy, and adopted objectives.” The “variable bonus component of executive remuneration should be subject to the company’s financial performance and ESG criteria,” using “key performance indicators (KPIs) included in its sustainability strategy.”

Box No. 2 – example of sector-specific and unique ESG criteria in the executive compensation policy

Some companies may also develop their own ESG criteria as part of the executive compensation policy to better align with the actual financial and especially extra-financial performance of the company. Example: a “Responsible Gaming” criterion developed by La Française des Jeux (FDJ) - SBF 120 included in the variable part of the CEO’s compensation. It is interesting to consider the development of such unique criteria, as they reflect a genuine consideration of ESG issues at the human scale of the company and society, contributing to greater awareness of these topics, as well as stronger effectiveness due to their closer proximity to operational activities. Developing company-specific criteria is a “best in class” practice that companies concerned with advancing their ESG criteria can explore, especially when these criteria are used to shape the executive compensation policy for executives, C-suite, etc. Only sector- specific ESG criteria would satisfy the requirements of proxies. Indeed, it is important to remember that proxies are responsible for advising shareholders on their voting policies, based on a number of financial and extra-financial requirements. Such a task requires reliance on reliable information that accurately reflects the company’s true performance. Translating a company’s extra-financial practices into distinct and identifiable ESG criteria is a prerequisite for any performance evaluation. For instance, in the financial and banking sector- which has the most advanced regulation in Europe today-some banks have had to define highly precise ESG performance criteria and measures (Figure 18), which would benefit from being generalised. Women Board Ready has been able to identify not only the types of criteria most commonly used but also the legitimacy of their selection by companies in the CAC 40. Among these indicators, some naturally pertain to specific sectors rather than others. Therefore, linking the choice of criteria to the sector is possible. Furthermore, beyond analysing the choice of criteria, it is also possible to assess their performance by the company. This is precisely the approach Women Board Ready used to highlight the extra-financial performance of certain CAC 40 companies based on dedicated sector-specific criteria. For Environmental criteria, the most commonly used are reduction of greenhouse gas emissions (particularly scopes 1 and 2), reduction of CO2, climate targets, percentage of decarbonized electricity consumed, reduction of energy consumption in customer solutions, recycling, sustainability training rates, and investments in climate funds. Some notable sector- specific practices include:

Figure 18:Evaluation of ESG-based compensation performance: variables and measures.

A. L’Oréal: Achieving “carbon neutral” status by 2025 for

all Group sites, improving energy efficiency, and using 100%

renewable energy in the cosmetics sector, where energy consumption

is significant.

B. L’Oréal: Replacing 100% of plastic packaging by 2030

with recycled or bio-based alternatives, with a 50% target by

2025, to address plastic pollution, a major issue for the FMCG

industry.

C. Dassault System: 90% of electricity consumed from decarbonised

sources, compared to 67% in 2021.

D. Bouygues: Increasing the percentage of recycled aggregates

in asphalt.

E. Renault: Achieving the quantitative goal of recycling

30,000 used vehicles in 2022.

F. Kering: Reducing carbon footprint (scope 3) to address

the significant energy consumption challenge in the fashion

sector.

G. Kering: Funding the Climate Fund for Nature with €180

million by the end of 2023.

H. Kering: By 2025, converting 1 million hectares in Kering’s

supply chain primarily to regenerative agriculture, and also

protecting significant areas outside the supply chain.

For Social criteria, the most commonly used are: workplace

safety, Diversity and Inclusion (D&I), gender representation in

C-suite/executives, employee engagement through internal surveys,

and youth employment. Some notable sector-specific practices

include:

I. L’Oréal: Assisting 100,000 people from disadvantaged

communities to access employment by 2030.

J. L’Oréal: 20% of the definitive acquisition of performance

shares subject to achieving environmental and social objectives

over a 4-year period from the grant date.

K. Vinci: Aiming for 30% female representation in the C-suite

by 2030 in an engineering and industrial sector where female

educational pathways are fewer.

L. Capgemini: Similarly, aiming for 30% women in executive

positions by 2025.

M. BNP: Labeling ISR (Socially Responsible Investment) of

the employee savings fund and adding three new ISR funds in

Asset Management in 2023, in a financial sector where integrating

ESG criteria is crucial for financing environmental and

social transitions.

N. Axa: Advancing diversity and inclusion in senior management

teams.

Regarding Governance, criteria are very limited, including aspects

such as ethics/integrity/compliance, customer satisfaction,

and the existence of a strategic plan. Nonetheless, these criteria

are few and sometimes surprising as they seem more like prerequisites

for good company functioning. Thus, sectorialisation of ESG

criteria is not only a guarantee of justification for the criteria but

also of effective alignment with the company’s actual performance.

However, just because the ESG criteria used by a company are relevant

to its sector and reflect genuine extra-financial performance

does not mean that the criteria applied to executive remuneration

based on ESG issues are the same or applied in the same way. For

example, Women Board Ready has identified ESG criteria within

the remuneration policies of CAC 40 companies, highlighting how

these criteria can be “restrictive.” In other words, the ESG criteria

in executive remuneration packages might be less stringent or demanding

than those in the company’s operational activities. Some

good practices include:

A. BNP: 5% of the general manager’s remuneration, out of

a 15% variable component, based on achieving RSE objectives

for key Group employees.

B. Crédit Agricole: 5% of remuneration based on the criterion

of “promoting youth employment and training,” out of 10%

of RSE societal criteria.

Nevertheless, some criteria appear limited or do not reflect genuine extra-financial performance, such as implementing a strategic plan or using vague criteria with no substance and no possibility of measurement, control, or verification. Given these challenges, the question of the “measurability” of ESG criteria within executive remuneration packages is inevitably posed.

Measurement: Given the challenges associated with selecting ESG criteria, the development of an “extra-financial performance assessment approach” requires a sector-specific approach. This involves determining sector-specific ESG criteria that are tailored to the socio-economic reality of the company to ensure genuine extra-financial performance, which can justify performance-based remuneration. However, the justification of remuneration based on extra-financial performance is directly contingent on the justification of the sector-specific ESG criteria used. This is crucial to avoid any accusations of bias or discretion, as previously discussed in the first part of this research document. In other words, focusing on both the quantitative and qualitative measurement of indicators derived from selected sector-specific ESG criteria-using specific methodologies and metrics-would help prevent the application of ESG criteria that are disconnected from the company’s realities or, worse, the use of a uniform, biased, and discretionary normative framework with no real connection to the executive management’s extra-financial performance. Consequently, this approach ensures the legitimacy of using extra-financial considerations to support performance-based remuneration.

Box 3 – Clarification of definitions: criterion, indicator, metric

The terms “criterion,” “indicator,” and “metric” are often used interchangeably without clarification of the semantic differences between them. For the sake of clarity, it is important to define each of these terms.

The noun “criterion” refers to a “principle or element used to judge, assess, or define something.” Therefore, a criterion is more about the principle that guides actions. ESG criteria include efforts to combat climate change, promote Diversity and Inclusion, or share value equitably. In contrast, the noun “indicator” refers to any “device that provides benchmarks and is used for measurement.” It is a collection of elements used to evaluate a company’s extra-financial issues. Examples include the existence of a greenhouse gas reduction plan, a programme to promote the professional integration of people with disabilities, or a profit-sharing scheme through employee savings plans.

Finally, the term “metric” was originally an adjective in French-except for its very specific use in poetic versification and mathematics-but has come to mean “unit of measurement” when used as a noun in everyday language. Derived from the English noun “metric,” which technically means “system or standard of measurement,” it now commonly denotes “unit of measurement.” In the context of ESG issues, common metrics include the carbon equivalent (Eq.t.CO2) for greenhouse gas emissions reduction or the percentage of women in senior positions (C-suite, executives, CEO). This definitional clarification is particularly useful for understanding the potentially biased and discretionary use of ESG themes in determining extra-financial performance that justifies additional remuneration. However, the ongoing development of these issues may account for such confusion.

The question of the measurability of metrics is not a trivial one. In fact, clearly established metrics—i.e., technically defined-enable the creation of robust indicators capable of representing the extra- financial performance of the highlighted ESG criteria. Therefore, the issue of measurability is central to the legitimacy of the metrics, indicators, and ESG criteria used to determine the remuneration policy for senior management based on extra-financial performance. However, in practice, this is not yet fully addressed. The FIR, in its latest campaign , lamented a still insufficiently formalized process for monitoring by the Board of Directors, which is often unspecified by companies. The Board is supposed to define in advance the ESG criteria that will govern part of senior management’s remuneration, while also evaluating, retrospectively, the achievement of these criteria through monitoring mechanisms designed to specify the achievement rate of these objectives, and finally to identify areas requiring adjustments based on external and internal developments. The FIR observes that the post hoc monitoring of objectives, including the reassessment of performance requirements for high achievement levels, remains problematic, with at best insufficiently detailed responses from CAC 40 companies, and in the worst cases, responses are absent. The level of information remains very limited or general, often only confirming that an annual evaluation of objectives and performance measures is carried out by the Board, without details or examples.

In light of this observation, the FIR concludes that while “the integration of E&S criteria into the remuneration of both executives and employees can truly reflect the incentive to implement ESG strategies, the vast majority of responses received do not allow for an evaluation of the alignment of remuneration with the material issues of companies, nor the effective control power that Boards can exert over these remuneration policies.” However, the demand for the integration of ESG criteria, indicators, and metrics aligns with the need for greater stakeholder satisfaction and is a central and recurring claim by proxies. As Proxinvest reminds us, “defining ESG performance conditions is recommended,” and “it is advised that the company opts for the key performance indicators (KPIs) chosen in its sustainable development strategy” because “criteria must be precise, verifiable, and consistent with their sustainability goals.” Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to limit the relevance of measurability to only extra-financial performance indicators. Indeed, the use of these indicators also contributes to this relevance. The measurability of an indicator is always contextualized; otherwise, it could be manipulated at will. Proxinvest outlines several conditions that must be met to ensure the minimum viability of indicators and metrics. Clearly, these conditions must ensure the link between senior management remuneration and their longterm performance. However, the long term should not be confused with achieving annual objectives over several years, and any performance realized within a period shorter than three years cannot be considered long-term. Another condition for the viability of criteria is the expression of goals in absolute terms to be achieved or in relative terms based on an indicator, relying on a medium to long-term strategic plan. Establishing a minimum performance threshold is another condition, for example, by recognising the median or average of a peer group as a reference level for performance evaluation, with no remuneration attributed if performance falls short of this level, or worse, setting a target below this average or median. Finally, a key condition is the multiplicity of indicators, some of which should be external to the company and compared to peers, while prohibiting “catch-up” criteria-those meant to compensate without additional performance for failures on other criteria. The final condition concerning the multiplicity of indicators and ESG criteria is a central issue for justifying senior management remuneration policies based on extra-financial performance. Indeed, it is possible to infer a positive correlation between the number of criteria and indicators on one hand, and the measurability of senior management’s extra-financial performance on the other. It is important to clarify that the number of criteria is not correlated with the measurability of indicators, as the presence of indicator B does not increase the measurability of indicator A. However, increasing the number of indicators could provide a more accurate measure of the true extra-financial performance of senior management, precisely because the plurality of indicators would increase the number of metrics used to calculate performance. This relationship between performance measurability and the multiplicity of indicators is confirmed by recent academic research.