- Submissions

Full Text

Significances of Bioengineering & Biosciences

Impact of Space-Dependent Thermal Conductivity on Heat Transfer in a Vertical Annulus with Asymmetric Surface Heating

Michael O Oni1*, Taiwo SYusuf1, Olaife H Adebayo1 and Luqman AAzeez2

1Department of Mathematics, Ahmadu Bello University, Nigeria

2Federal College of Education, Nigeria

*Corresponding author: Michael O Oni,Department of Mathematics, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria

Submission: September 10, 2020 Published: October 22, 2020

ISSN 2637-8078Volume4 Issue1

Abstract

This technical brief investigates the impact of space dependent thermal conductivity on temperature distributions and rate of heat transfer of some fluids in a porous annulus. The heat transport equation is derived with a linear thermal conductivity model. Exact solution of the energy equation is obtained after using suitable dimensionless parameters. Results indicate that increase in coefficient of thermal conductivity leads to a corresponding increase in fluid temperature as well as Nusselt number. In addition, fluids with higher Prandtl number are found to be a good insulators.

Keywords: Space-dependent; Thermal conductivity; Vertical annulus; Asymmetric heating; Prandtl number; Nusselt number

Introduction

Over the past two centuries, thermal conductivity (often denoted k, λ, or κ) is the property of a material to conduct heat. It is evaluated primarily in terms of Fourier's law for heat conduction. Materials of high thermal conductivity transfer heat faster than materials with lower thermal conductivity. Correspondingly, materials of high thermal conductivity are widely used in heat sink applications and materials of low thermal conductivity are used as thermal insulation. The thermal conductivity of a material may depend on temperature. Thermal conductivity is important in material science research, electronics, building insulation and related fields, especially where high operating temperatures are achieved. The impact of temperature dependent thermal conductivity has been studied over decades and interesting results have been obtained. Prasad et al. [1] studied the effects of variable fluid properties on the hydromagnetic flow and heat transfer over a non-linearly stretching sheet. Later, Animasaun [2] investigated the effect of thermophoresis, variable viscosity and thermal conductivity on free convective heat and mass transfer of non-darcian MHD dissipative casson fluid flow with suction and order of chemical reaction. He concluded that viscosity parameter as well as thermal conductivity parameter decreases fluid temperature. Other works on temperature dependent thermal conductivity can be found in [3-6].

Understanding heat transfer with space dependent thermal conductivity induced by temperature difference at the surfaces of the cylinders would give better outcome in laboratories experiment, material science, polymer factories and florescent bulbs industries. Liu and Yang [7] studied length-dependent thermal conductivity of single extended polymer chains. Also, Chen et al. [8] presented an inverse problem in estimating the space dependent thermal conductivity of a functionally graded hollow cylinder. They concluded that the inverse Levenberg-Marquardt method (LMM) are still reliable as the measurement errors are considerable low. Later, Xu et al. [9] investigated length-dependent thermal conductivity in suspended single-layer graphene. They found that at 300K, thermal conductivity keeps increasing and remains logarithmically divergent with sample lengths much larger than average phonon mean free path. In other work, Louis [10] analyzed the effect of space-dependent thermal conductivity on the steady central temperature of a cylinder. Other related articles where thermal and heat transfer analysis in cylindrical geometries are carried out can be found in [11-16]. The aim of this present work is to analyse the impact of variable thermal conductivity on temperature distributions and rate of heat transfer of some carefully selected fluid which are of high engineering applications. Section one gives the introduction of the work while sections 2, 3 and 4 respectively give the mathematical analysis, results and discussion and conclusion.

Mathematical Analysis

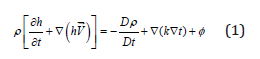

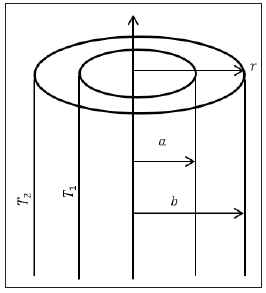

Consider a porous annulus bounded by two vertical cylinders of radius a and b respectively for the inner and outer cylinder. Fluid is assumed to be entering the annulus through the surface r=a and going out at the surface r=b at the same rate (continuity satisfied). The inner surface of outer cylinder (r=b) is assumed to be heated with temperature (T2) greater than the surrounding fluids having temperature (T0) and the outer surface of inner cylinder (r=a) is heated to a temperature (T1) as shown in (Figure 1). The energy equation governing the temperature distribution is given by:

Figure 1:

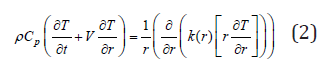

where h is the specific enthalpy, is the dissipation function, T is the absolute temperature and V is the radial velocity, is the fluid density and k is the thermal conductivity. Neglecting the specific enthalpy and dissipation function and also assuming that the flow is incompressible and along -direction only (thermally fully developed); we have:

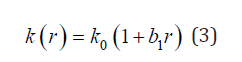

In this problem, we assume the temperature distribution to be steady and thermally fully developing with constant radial velocity . Since the temperature of inner surface of the outer is greater than that of outer surface of inner cylinder T2>T1, the thermal conductivity is assumed to vary directly with space by the linear function

where b1 is the coefficient of variation of the fluid thermal conductivity (1/m). It is well known that the thermal conductivity of gases increases with increase in temperature, and the reverse for liquid. Hence the fluid closer to surface r=b is assumed to have higher thermal conductivity than the fluid closer to the surface

r=a.

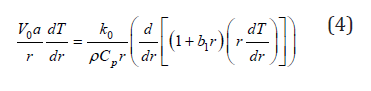

Under these assumptions, the energy equation reduces to:

Subject to

T=T1 at r=a

T=T2 at r=b (5)

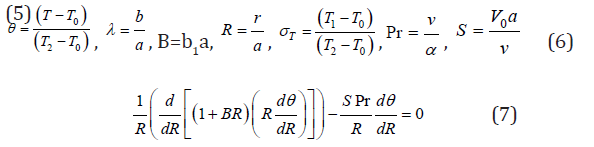

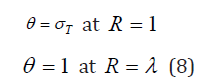

Using the following dimensionless quantities in equations (4), (5)

subject to the following dimensionless boundary conditions

where Pr is the Prandtl number, S is the suction or injection parameter, T0 is the ambient temperature, B is the dimensionless number governing the variation of thermal conductivity and is cylinder surface temperature difference ratio. It is good to note that when B=0, it corresponds to constant thermal conductivity Jha and Babatunde [16].

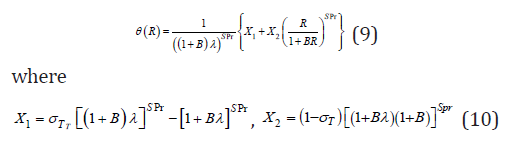

Solving Eq. (7) subject to (8), we have:

where

The Nusselt number at the surfaces of the cylinders is given in dimensional form as:

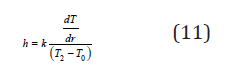

, where h is the heat transfer coefficient and is defined as (11)

So that by the use of Eq. (6), Eq. (11) becomes

Results and Discussion

The solutions obtained are seen to be govern by Prandtl number (Pr), thermal conductivity variation parameter (B), suction/injection parameter (S), radius ratio and cylinder surface temperature difference ratio . We have considered different applicable fluids dictated by Prandtl number: Liquid Lithium are used to cool the fusion reactors blankets, it is also used for superconducting magnets, such as those needed in nuclear magnetic resonance imaging and nuclear magnetic resonance Liquid Lithium (Pr=0.065), Helium (Pr=0.261), the boiling point of helium is the least when compared to any other liquid. It is used to obtain the lowest temperatures required in lasers. Helium is also used in nuclear reactors as a cooling gas and used as a flow-gas in liquid-gas chromatography. It finds its application in airships and helium balloons. In addition, helium balloons are used to check the weather of a particular region. Helium is preferred over hydrogen though hydrogen is cheaper, as helium is readily available and hydrogen is highly inflammable. Hence due to safety issues helium is preferred in aircrafts [17]. Oxygen (Pr=0.63), air (Pr=0.71) and ammonia (Pr= 1.38) on the other hand is use as cleaning, bleaching, deodorizer, drugs, dyes and fertilizer Ried et al. [17].

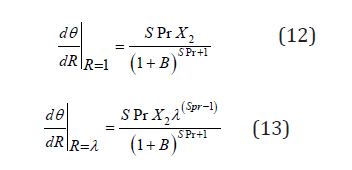

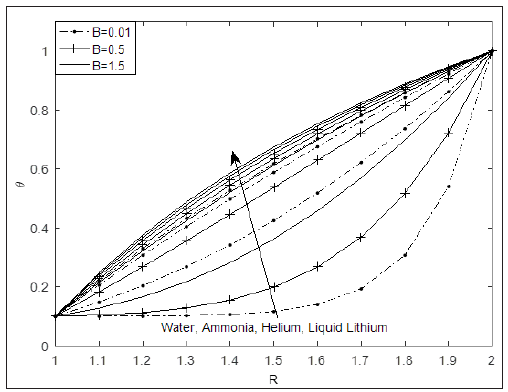

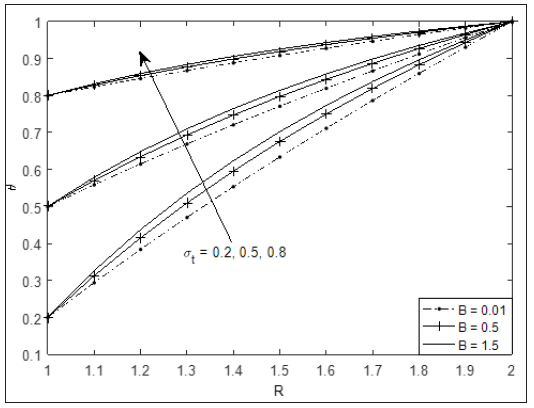

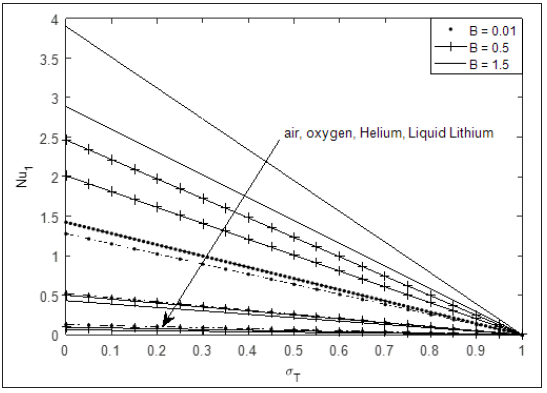

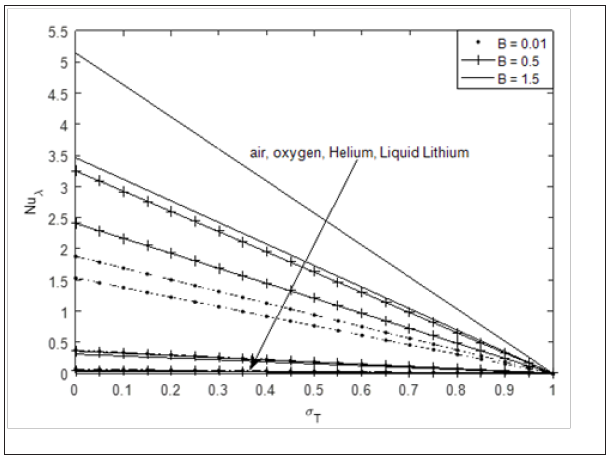

Figure 2 depicts temperature profile at different values of thermal conductivity variation parameter (B) for different fluids at fixed value of suction/injection and radius ratio. It is seen that temperature is highest in Liquid Lithium (which has the lowest Prandtl number) and lowest for water (which has the highest Prandtl number). This can be attributed to the fact that increase in Prandtl number always reduce fluid temperature. In addition, the role of space dependent thermal conductivity is to increase fluid temperature in the annulus. Figure 3 exhibits combined effect of cylinder temperature difference ratio and thermal conductivity variation parameter on fluid temperature. It is observed that fluid temperature increases with increase in . Moreover, for higher value of , (which almost corresponds to symmetric heating), the significant of is seen to be reduced compare of lower value of . Figures 4 & 5 present the impact and B for different fluids at the outer surface of inner cylinder and inner surface of cylinder, respectively. From both figures, the rate of heat transfer is seen to increase with increase in B but decreases with increase in . In addition, the rate of heat transfer is highest for atmospheric air and lowest for liquid Lithium. This explains why Liquid Lithium and helium are used as nuclear plant coolant.

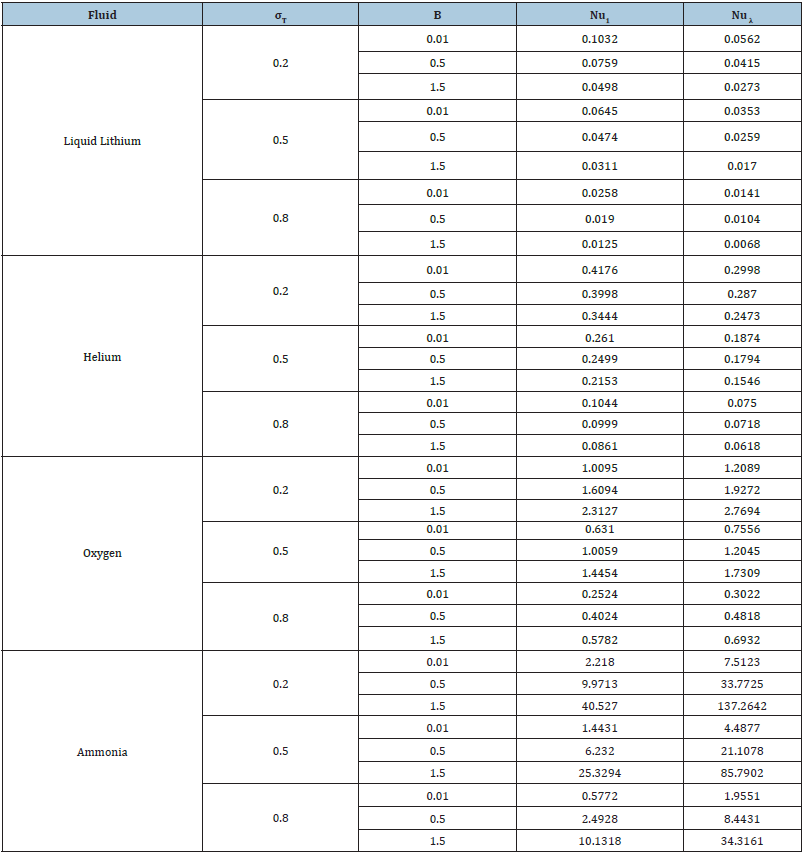

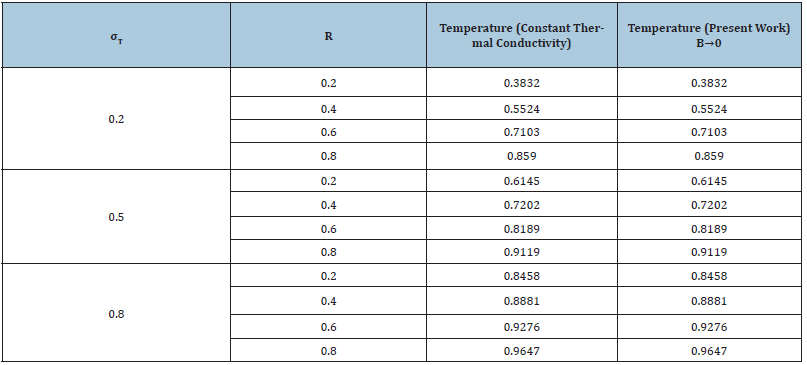

Table 1 gives the values for rate of heat transfer for different values of governing parameters. It is observed that Nusselt number of fluid with lower Prandtl number (Lithium and Helium) decreases with increase in and B. The reverse trend is noticed for fluid with higher Prandtl number. (Table 2) on the other hand presents the validation of the present work with the absence of variable thermal conductivity . This comparison gives an excellent agreement.

Results and Discussion

The solutions obtained are seen to be govern by Prandtl number (Pr), thermal conductivity variation parameter (B), suction/injection parameter (S), radius ratio and cylinder surface temperature difference ratio . We have considered different applicable fluids dictated by Prandtl number: Liquid Lithium are used to cool the fusion reactors blankets, it is also used for superconducting magnets, such as those needed in nuclear magnetic resonance imaging and nuclear magnetic resonance Liquid Lithium (Pr=0.065), Helium (Pr=0.261), the boiling point of helium is the least when compared to any other liquid. It is used to obtain the lowest temperatures required in lasers. Helium is also used in nuclear reactors as a cooling gas and used as a flow-gas in liquid-gas chromatography. It finds its application in airships and helium balloons. In addition, helium balloons are used to check the weather of a particular region. Helium is preferred over hydrogen though hydrogen is cheaper, as helium is readily available and hydrogen is highly inflammable. Hence due to safety issues helium is preferred in aircrafts [17]. Oxygen (Pr=0.63), air (Pr=0.71) and ammonia (Pr= 1.38) on the other hand is use as cleaning, bleaching, deodorizer, drugs, dyes and fertilizer Ried et al. [17].

Figure 2 depicts temperature profile at different values of thermal conductivity variation parameter (B) for different fluids at fixed value of suction/injection and radius ratio. It is seen that temperature is highest in Liquid Lithium (which has the lowest Prandtl number) and lowest for water (which has the highest Prandtl number). This can be attributed to the fact that increase in Prandtl number always reduce fluid temperature. In addition, the role of space dependent thermal conductivity is to increase fluid temperature in the annulus. Figure 3 exhibits combined effect of cylinder temperature difference ratio and thermal conductivity variation parameter on fluid temperature. It is observed that fluid temperature increases with increase in . Moreover, for higher value of , (which almost corresponds to symmetric heating), the significant of is seen to be reduced compare of lower value of . Figures 4 & 5 present the impact and B for different fluids at the outer surface of inner cylinder and inner surface of cylinder, respectively. From both figures, the rate of heat transfer is seen to increase with increase in B but decreases with increase in . In addition, the rate of heat transfer is highest for atmospheric air and lowest for liquid Lithium. This explains why Liquid Lithium and helium are used as nuclear plant coolant.

Figure 2: Temperature profile for different fluids varying B at S=2.0, σT=0.1, λ=2.0.

Figure 3: Temperature profile of liquid lithium varying B and σT at λ=2.0, S=2.0.

Figure 4:

Figure 5: Nusselt number of fluids for different values of B and σT at S=2.0, λ=2.0, R=1.

Table 1: Rate of heat transfer of different fluid for different values of σT and B at S=2.0, λ=2.0.

Table 2: Validation of fluid temperature result using liquid lithium at different R and σT and B at S=2.0, λ=2.0.

Table 1 gives the values for rate of heat transfer for different values of governing parameters. It is observed that Nusselt number of fluid with lower Prandtl number (Lithium and Helium) decreases with increase in and B. The reverse trend is noticed for fluid with higher Prandtl number. (Table 2) on the other hand presents the validation of the present work with the absence of variable thermal conductivity . This comparison gives an excellent agreement.

Conclusion

This paper examines an exact solution to show the impact of space dependent thermal conductivity on some fluids in a porous annulus with asymmetric surface heating. The governing energy equation is derived and closed form expressions are obtained for temperature and rate of heat transfer. Based on depicted graphs and tables, the following major conclusions can be drawn:

- Fluid temperature as well as rate of heat transfer increase with increase in thermal conductivity variation parameter.

- Temperature is higher for fluids with lower Prandtl number (liquid lithium) and lower for fluids with higher Prandtl number (water)

- Fluid temperature as well as rate of heat transfer becomes independent of governing parameters for higher value of , .

- It is hoped that the results obtained in this paper will not only provide useful information for industrial applications (quality control during manufacturing process), but also serve as an improvement on the previous studies.

References

- Prasad KV, Vajravelu K, Datti PS (2010) The effects of variable fluid properties on the hydromagnetic flow and heat transfer over a non-linearly stretching sheet. Int J Ther Sci 49: 603-610.

- Animasaun I (2015) Effect of thermophoresis, variable viscosity and thermal conductivity on free convective heat and mass transfer of non-darcian MHD dissipative casson fluid flow with suction and nth order of chemical reaction. J Nigerian Math Society 34(1): 11-31.

- Khan Y, Wu Q, Faraz N, Yildirim A (2011) The effects of variable viscosity and thermal conductivity on a thin film flow over a shrinking/stretching sheet. Compt. Math Appl 61(11): 3391-3399.

- Abd El Aziz M (2007) Temperature dependent viscosity and thermal conductivity effects on combined heat and mass transfer dimensional flow over a stretching surface with ohmic heating. Meccanica 42(4): 375-386.

- Aksoy IG (2013) Thermal analysis of annular fins with temperature-dependent thermal properties. Appl Math Mech 34: 1349-1360.

- Chen CJ, Ozisik MN (1994) Optimal convective heating of a hollow cylinder with temperature dependent thermal conductivity. Appl Sci Res 52: 67-79.

- Liu J, Yang R (2012) Length-dependent thermal conductivity of single extended polymer chains. Phys Rev B 86(10): 104307.

- Chen WL, Chou HM, Yang YC (2013) An inverse problem in estimating the space dependent thermal conductivity of a functionally graded hollow cylinder. Composites part B: Engineering 50: 112-119.

- Xiangfan Xu, Luiz FC Pereira, Yu Wang, Jing Wu, Kaiwen Zhang (2014) Length-dependent thermal conductivity in suspended single-layer graphene. Nat Commun 5: 3689.

- Louis CB (2001) The effect of space-dependent thermal conductivity on steady central temperature of a cylinder. J Heat Transfer 124(1): 195-197.

- Michael O Oni, Basant K Jha (2019) Theoretical analysis of transient natural convection flow in a vertical microchannel with electrokinetic effect. Journal of Taibah University for Science 13(1): 1087-1099.

- Jha BK, Oni MO, Aina B (2016) Steady fully developed mixed convection flow in a vertical micro-concentric-annulus with heat generating/absorbing fluid: an exact solution. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 9(4): 1289-1301.

- Aung W, Worku G (1986) Theory of fully developed, combined convection including flow reversal. J Heat Transfer 108(2): 485-488.

- Oni MO (2017) Combined effect of heat source, porosity and thermal radiation on mixed convection flow in a vertical annulus: An exact solution. Eng Sci Tech Int J 20(2): 518-527.

- Jha BK, Oni MO (2018) Fully developed mixed convection flow in a vertical channel with electrokinetic effects: Exact solution. Multidiscipline Modelling in Materials and Structures 14(5): 1031-1041.

- Jha BK, Aina B (2018) Mathematical modelling and exact solution of steady fully developed mixed convection flow in a vertical micro-porous-annulus. Journal of Afrika Matematika 26: 1199-1213.

- Reid CR, Prausnitz JM, Poling BE (1987) Properties of gases and liquids. In: 4th (edn.), McGraw-Hill, USA. pp. 1-741.

© 2020 James F Welles. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)