- Submissions

Full Text

Research in Medical & Engineering Sciences

The Malachite Wen-Myeloid Sarcoma

Anubha Bajaj*

Department of Histopathology, AB Diagnostics, New Delhi, India

*Corresponding author:Anubha Bajaj, Department of Histopathology, AB Diagnostics, New Delhi, India

Submission: February 10, 2023Published: February 13, 2023

ISSN: 2576-8816Volume10 Issue2

Opinion

Contingent to World Health Organization (WHO) classification, myeloid sarcoma is denominated as a tumefaction comprised of myeloblasts amalgamated at an anatomical site divergent from the bone marrow which engenders distortion of normal tissue architecture. Generally, myeloid sarcoma is contemplated to be equivalent to and concurrent with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), although lesions may occur in isolation. Additionally designated as granulocytic sarcoma, chloroma or extramedullary myeloid tumour, myeloid sarcoma categorically represents as a distinct tumefaction associated with architectural effacement of circumscribing soft tissue. Myeloid sarcoma may emerge as a de novo lesion or manifest as therapy related myeloid neoplasm or as disease progression within myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN), myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or myelodysplastic / myeloproliferative neoplasm (MDS / MPN). In contrast, leukaemia cutis (LC) is a nonspecific terminology adopted to describe cutaneous infiltration of neoplastic leukocytes which configure as mature or immature myeloid or lymphoid cellular components. Nevertheless, as per WHO classification criterion, leukaemia cutis remains nonequivalent to myeloid sarcoma [1,2]. Leukaemia cutis may emerge in subjects delineating non acute myeloid leukaemia (non-AML), Myeloproliferative Neoplasm (MPN), Myelodysplastic Syndrome (MDS) or Myelodysplastic / Myeloproliferative neoplasm (MDS / MPN) as Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia (CMML).

An estimated 50% of myeloid sarcoma delineate cytogenetic anomalies. Exceptionally, genomic discrepancies within concordant bone marrow karyotype are discerned, indicative of clonal cellular evolution. Myeloid sarcoma exhibits cytogenetic and molecular anomalies simulating acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). Commonly, chromosomal translocations as t (8;21) (q22; q22) RUNX1-RUNX1T1 or inv (16) (p13.1q22) CBFB-MYH11 may be encountered [1,2]. Generally, secondary myeloid sarcoma exhibits a complex karyotype. Genomic mutations within NRAS, NPM1, KRAS, FLT3-ITD and IDH2 genes are frequently discerned.

Instances concurrent with pre-existing myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) enunciate JAK2 V617F genetic mutation. Besides, occurrence of BCR-ABL1 genetic fusion represents disease progression within chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) [1,2]. Myeloid sarcoma may incriminate diverse sites as cutaneous surface, orbit, cheek, soft tissue, paravertebral region, pelvis, skull, central nervous system, pleura, mammary glands, abdominal cavity, gastrointestinal tract, hepatic parenchyma, middle ear, bone, femur, elbow joint, gums, nasopharynx, intracanal, maxillary sinus, mediastinum, lymph nodes or testis although no site of tumour emergence is exempt. No age of disease occurrence is exempt [1,2]. Of obscure aetiology, myeloid sarcoma is posited to arise from chemokines or chemokine receptor interaction with consequent migration of leukaemia cells into adjoining cutaneous surfaces. Also, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and integrin may induce migration of leukaemia cells and disruption of blood brain barrier. Molecules such as CXCR4, CXCL12 and CD56 appear associated with specific sites of emergent myeloid sarcoma [2,3].

Contingent to localization of the neoplasm, myeloid sarcoma demonstrates a variable clinical representation and is categorized as ~primary or de novo myeloid sarcoma is devoid of pre-existing diagnosis of myeloid neoplasm or acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) ~secondary myeloid sarcoma demonstrates concurrent or preceding myeloid neoplasm or acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) ~isolated myeloid sarcoma is comprised of primary or secondary myeloid sarcoma in the absence of incriminated bone marrow [2,3]. Myeloid sarcoma may represent with asymptomatic lesions or manifest cogent clinical symptoms as tumour nodules, bluish lesions, exophthalmos, orbital soft tissue swelling, ptosis, facial nerve paralysis, fatigue, pain, pyrexia, weight loss, enlarged lymph nodes, paralysis of 7th nerve, deafness, otitis, respiratory tract infection, paresis, dyspnoea, joint pain, apathy, Horner’s syndrome, petechiae, sweating, hepatosplenomegaly, abdominal distension, constipation, anuria or excessive enlargement of head circumference [2,3]. Upon microscopy, incriminated tissue demonstrates partially effaced architecture. Neoplastic cells may configure cohesive cellular nests or infiltrate as singular file of cells. The neoplasm is comprised of granulocytic or monocytic precursors. Exceptionally, foci of erythroblastic or megakaryoblastic differentiation may be discerned. Neoplastic cells demonstrate elevated nucleocytoplasmic ratio with well dispersed nuclear chromatin. On account of significant cellular proliferation and turnover, mitotic figures and apoptotic bodies are numerous [2,3].

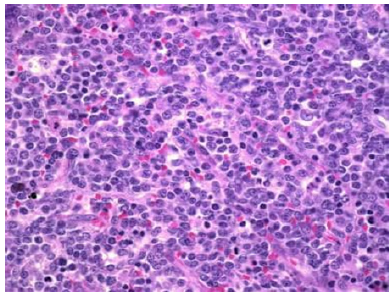

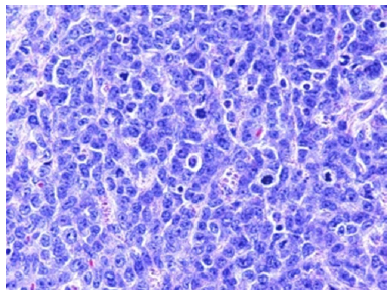

Myeloid sarcoma appears immune reactive to CD68/KP1, lysozyme, CD33, CD43, CD45, myeloperoxidase (MPO), CD117, CD56, CD34, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), CD71, glycophorin, CD42b and CD61 [4,5]. Myeloid sarcoma appears immune non-reactive to lymphoid lineage markers as CD20, CD3, CD19 and PAX 5. However, neoplasm may depict chromosomal translocation t (8;21) (q22; q22.1) RUNX1-RUNX1T1 (Figure 1&2).

Figure 1:Myeloid sarcoma demonstrating cohesive soft tissue aggregates and single files of diverse erythroid, granulocytic and monocytic precursors [6].

Figure 2:Myeloid sarcoma delineating cohesive cellular clusters, aggregates and single cell files of granulocytic and monocytic precursors [7].

Myeloid sarcoma requires segregation from neoplasms such as lymphoblastic lymphoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma, diffuse large B cell lymphoma, histiocytic sarcoma, non haematopoietic tumours, extra- medullary haematopoiesis or blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm [4,5]. Appropriate discernment of myeloid sarcoma requires application of a wide panel of immunohistochemistry in order to circumvent misrepresentation of disease. Absence of concurrent bone marrow incrimination represents with lack of fresh tissue necessitated for karyotyping or flow cytometry. However, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies and gene mutation analysis may be beneficially employed upon formalin fixed, paraffin embedded (FFPE) sections. Diagnostic features are contingent to tumour localization and concordant incrimination of bone marrow [4,5]. Appropriate therapy of myeloid sarcoma appears devoid of universal consensus or guidelines. Therapeutic strategies are contingent to disease representation, disease stage as initial or relapsed disease and institutional experience. Precise treatment is comprised of systemic chemotherapy, localized surgical intervention or radiation therapy, bone marrow transplantation and target therapy. Prognostic outcomes of myeloid sarcoma simulate survival outcomes of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). Cogent tumour site may contribute to prognostic outcomes [4,5].

References

- Aslam HM, Veeraballi S, Saeed Z, Weil A, Chaudhary V (2022) Isolated myeloid sarcoma: A diagnostic dilemma. Cureus 14(1): e21200.

- Shahin OA, Ravandi F (2020) Myeloid sarcoma. Curr Opin Hematol 27(2): 88-94.

- Samborska M, Barańska M, Wachowiak J, Sadowska JS, Thambyrajah S, et al. (2022) Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of myeloid sarcoma in children: The experience of the polish pediatric leukemia and lymphoma study group. Front Oncol 12: 935373.

- Bakst R, Powers A, Yahalom J (2020) Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations for extramedullary leukemia. Curr Oncol Rep 22(7): 75.

- Xu G, Zhang H, Nong W, Li C, Meng L, et al. (2020) Isolated intracranial myeloid sarcoma mimicking malignant lymphoma: a diagnostic challenge and literature reviews. Onco Targets Ther 13: 6085-6092.

- Figure 1 Courtesy: Medscape reference

- Figure 2 Courtesy: Diagnostic pathology-biomed central

© 2023 Anubha Bajaj. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)