- Submissions

Full Text

Research in Medical & Engineering Sciences

Smoking Cessation a Review Article

Sarvath Ali*

University of Cincinnati, USA

*Corresponding author: Sarvath Ali, University of Cincinnati, 104 Louis Ave, Lehigh Acres, FL 33936, USA

Submission: January 02, 2018; Published: January 10, 2018

ISSN: 2576-8816Volume3 Issue1

Abstract

Introduction: This article is a retrospective review of research articles on smoking cessation obtained through a search of selected databases from 1, Dec 2017 back to 31 Dec 2000. The purpose and goal of this report is to bring awareness among the population. Additionally, to provide data for professionals in public health and policymakers, to help make recommendations based on effective cessation intervention evidence. Also, to provide information to youth who indulge in tobacco smoking of the trends, prevalence, consequences and to inspire engaging in programs for smoking cessation.

Methods: The articles published from 2000 to 2017 were identified retrospectively through electronic databases such as Medline, PubMed, and EBSCOhost. Peer review articles relevant to smoking cessation were chosen. Statistical information was gathered and further analyzed. Besides web- based resources, other important resources such as the Center for Disease Control (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) were also utilized for review.

Background: Even though several preventive measures have been taken by the governments and several organizations, smoking remains a constant and severe problem in communities all over the world. Smoking-related diseases claim an estimated six million lives each year out of which 600,000 deaths were from exposure to second-hand smoke, though it is entirely preventable (WHO, 2014).

Introduction

An estimated 126 million Americans are regularly exposed to secondhand smoke each year [1]. More than 43 million adults are current smokers in the USA. Eighty-eight percent of those adults who started smoking at their youth (age 11-12 years) almost became an addict when they turned 14. Globally, as well as in the US, tobacco smoking has been the leading cause of preventable death. The prevalence of youth smoking is high, although some resources have been dedicated to this problem and the variety of interventions that have been tried to prevent smoking is a big concern from a public health perspective. As there are numerous health benefits of smoking cessation, most individuals who smoke express a desire to quit smoking. Studies show that most smokers in the United States and the United Kingdom report that they want to stop or intend to quit smoking at some point in life [2].

In India, tobacco's associated mortality is the highest in the world, an estimated 700,000 annual deaths attributable to tobacco use [3]. Whereas, the lowest smoking rates for men can be found in Nigeria, Barbuda, and Antigua. For women, smoking rates are lowest in Eritrea, Cameroon, and Morocco [4].

A multitude of non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions now exist to aid smokers in cessation. The financial burden imposed by cigarette smoking is enormous. Smoking- related illness in the United States costs $100 billion each year in medical expenses and $100 billion in lost productivity due to premature mortality. Cigarette industries are spending billions of dollars on advertising tobacco products, attracting specifically adolescents and young adults which fuel the existing burden. The primary cause of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and lung cancer in adults has been cigarette smoking. There is an association between smoking and periodontal disease in children and adolescents. Smoking is responsible about 90% of the lung cancer deaths in the United States. It is responsible for 30% of all cancer deaths universally. Cigarette smokers have a lower level of lung function than those persons who have never smoked. Smoking hurts young people's physical fitness regarding both performance and endurance, even among young people trained in competitive running. On average, a person smoking a pack or more of cigarettes per day lives seven years less than the person who never smoked [5]. In 2007, 1,800 Hispanic women and almost 3,000 Hispanic men died of lung cancer. Cigarette smokers are also known to possess a greater risk than nonsmokers for heart attack (in the same year, about 3,000 Hispanic women and nearly 3,800 men died from heart attack. Smokers have a 70% greater chance of dying from coronary heart disease than non-smokers [6].

Overall, lung cancer is known to be the leading cause of cancer deaths among African Americans. Multiple factors are associated with tobacco use such as social, physical and environmental. Young people are more likely to use tobacco if their peers use tobacco. Perceived smoking is acceptable or normative among their peers. They expect positive outcomes from smoking, such as surviving with stress, anxiety, and depression. Parental and sibling smoking may also promote smoking among children and youth in a household where perceived parental approval plays a significant role in adolescent smoking. In Hispanic and Asian communities, families live intimately with each other. Parents have control over their children and watch their activities, and vice versa offspring also respect parents and elders. Hispanic youth are more likely than other young people to be protected from second-hand smoke by smoking bansat home. Seventy percent of Hispanic households do not allow smoking in their homes. Parenteral perceived disapproval of smoking is a protective factor against adolescent smoking (Mc Causland, 2005). Other factors like low socioeconomic status, lack of parental support or involvement, accessibility, availability, low level of academic achievement, low self-image and aggressive behavior have been associated with youth smoking [7]. Peer pressure is a significant factor in their decision-making process. There are many studies showing that the influence of peers is especially powerful in determining when and how young people first try a cigarette. The smoking rate among children and young adults who have three or more friends who smoke are ten times higher than those who report that none of their friends' smoke [8].

Health Impact on Smoking

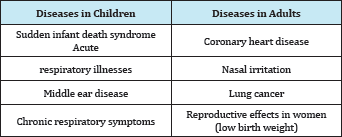

Secondhand smoke exposure puts family members of smokers at an increased risk. The following table illustrates the various health impacts in children and adults: (Table 1).

Table 1: WHO, 2011.

Other benefits of quitting smoking are reduced chances of impotence, having difficulty getting pregnant, having premature births, babies with low birth weight and miscarriage. In children, the risk factors of many second-hand smoking such as asthma and other respiratory diseases decrease [9].

After quitting smoking, there are numerous physical and emotional effects the body experiences. These effects consist of are both short-term and long-term benefits. The short-term benefits; Which can commence as soon as 20 minutes past quitting, include heart rate and blood pressure decrease. Carbon monoxide level drops to normal after 12 hours. There is an improvement in blood circulation and lung function after two to twelve weeks of quitting. Shortness of breath and coughing decrease after one to nine months of stopping. Subsequently, two to three weeks following cessation, several regenerative processes begin to take place in the body. The long-term benefits of quitting reduce the risk of coronary heart disease after one year to one and a half. Five years past quitting, the probability of stroke is reduced to that of a nonsmoker. The potential for lung cancer, cancer of mouth, throat, esophagus, bladder, cervix and pancreas reduces to about half of that for a smoker. Within 15 years of cessation, almost all the recuperative processes are completed. The risk of heart disease is no greater than someone who has never smoked a cigarette [5].

The advantages of quitting smoking compared to those who continued to smoke are huge. Life expectancy is increased compared to those who continued to smoke. The probability of suffering from another heart attack is reduced by 50% for people who quit smoking after having a heart attack or following the onset of life-threatening disease [10].

Dependence and Relapse

The addictive effect of nicotine once smoked, makes hard to quit smoking. Early initiation increases the likely-hood of habituation, and continuous tobacco smoking eventually ends up in addiction. People who begin to smoke at a very young age are more likely to develop severe levels of smoking than those who start a later age [11]. Tobacco addictions should be treated as a chronic disease with a constant risk of relapse [12].

Based on literature review, many studies have proved that tobacco is apparently more addictive than any other substance abuse. According to one study high rates of relapse among smoking quitters occurs due to the addiction potential of tobacco. It is reported that brief counseling has resulted in a quit rate of 55% the relapse rate among quitters was 23% [13]. The current improved knowledge of the neurobiology of nicotine addiction has significant implications for the management of its dependency [14].

Challenges for Quitting

There are many challenges and barriers to quitting. There are three critical challenges that one should be acquainted with before planning to assist smokers to quit or attempt to quit. All people do not have the same reasons why they smoke and why they could not quit. The reasons have been classified into three categories.

1) Physiological addiction,

2) behavioral and environmental social, and

3) Emotional or psychological connections [15].

Smoking Cessation, Smoking Prevention and Methods to Quit

The Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence -Clinical Practice Guideline, issued by the United States Department of Health and Human Services, recommends the 5A's and 5 R's approach that should be addressed in a motivational counseling intervention to help those who are not ready to quit [11]. The below figure illustrates the motivational counseling interventions: (Figure 1), (Table 2).

There are seven first-line medications available that are known to increase long-term smoking abstinence: Nicotine

Figure 1: Tool Kit: WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008: the MPOWER Package.

Table 2: WHO, 2014.

Inhaler, Nicotine gum, Bupropion SR Nicotine lozenge, Nicotine patch, Nicotine nasal spray, and Varenicline [12]. Current information on adolescence tobacco use prevention has proposed that macro-level approaches can be effective in reducing the prevalence of tobacco use among adolescents. The stronger tobacco control policy that increased tobacco taxation and countermarketing campaigns have all proven to be successful strategies for reducing youth tobacco use [16].

The use of counseling and pharmacotherapy together has been reported as the most effective strategy to achieve tobacco abstinence. The time spent on counseling is very effective since it has got a significant association between the time devoted to counseling a person quitting smoking and their chances of quitting. According to WHO guidelines, more than one type of pharmacotherapy should be offered in combination, if appropriate, for a prolonged period [12].

After identifying and understanding different sub-groups, various communication strategies should be developed for specific focus groups that enhance the impact of health information. The Community Preventive Services recommends the use of "mass- reach health communication interventions" e.g. television and radio broadcasts, newspapers, billboards, built on solid evidence for their advantageousness in preventing or reducing cigarette smoking and increasing use of cessation services like quit lines. Regarding the use of media, studies suggest that the success of different types of smoking cessation messages may vary by socioeconomic status, predominantly income and education status. Cessation programs must be custom-made to focus on the envisioned audience rather than just providing information [17].

Nicotine Replacement Therapy

Among the currently available smoking-cessation treatments, including nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion and varenicline are well-known pharmacological interventions to raise the chances of quitting tobacco smoking, mainly when combined with health education and counseling programs. Various studies have shown that tobacco cessation assistance provided by health professionals (physicians, nurses, dentists, pharmacists and other health care workers) enhances the quit rate among their patients [18].

Almost all forms of NRT gum, transdermal patches, nasal sprays, inhalers and sublingual tablets can help persons who make a quit attempt and increases their chance of successfully quitting smoking by 50% to 70% irrespective of any setting. The purpose of NRT is to briefly replace considerable nicotine from cigarettes and to decrease the stimulus to smoke and avoid nicotine withdrawal symptoms consequently to ease the transition from smoking to complete abstinence [9].

Quit-Lines

Quit-line is a tobacco cessation program which is a phone based service that helps tobacco users quit smoking. Today, residents of all 50 states in U.S. and Canada, have access to Quit lines services. In the recent years, Quit-lines has been able to become a critical part of the tobacco control efforts that are ongoing in the United States. The universal access, demonstrated efficacy and the convenience of remote counseling via telephone have all led to the quick and widespread adoption of Quit lines in the North American region [19].

Currently over 53 countries have at least one national toll-free quit line with a person available to provide quit line cessation services, with access to its population. All the 50 states of USA and Canada are having multiple quit lines operated by Federal government, state government and Non-governmental organizations. Out of 53 countries, 32 (60%) of them are wealthy countries and four countries (8%) are of low income and 17 of them are middle-income countries which made up only18% of all middle- income countries in the world, have at least one national toll-free quit line. There is the noticeable difference in reach as well as type, quality, quantity, volume and of services provided by different quit lines. The counselors and supervisors working in quit lines are well trained by the psychiatrists for operational purpose of smoking cessation assistance. Quit-lines are established in collaboration with health care system, health care providers, nongovernmental organizations, and governments both local and national. Among the primary methods used by countries to promote quit line services are media advertisements (newspapers, television, radio or flyers). Some countries, including Brazil, New Zealand, South Africa, and all the European Union (EU), have printed the quit line number on cigarette packets together with health warnings. In spite of their widespread presence, information including international data on how Quit-lines services operate in practice and their outcome is not readily available [13].

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Very few studies have been confirmed that the complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for tobacco cessation, like, yoga, hypnosis, herbal products, acupuncture, relaxation, and massage therapy have been tried and were successful. However, use of complementary and alternative medicine treatments and a higher level of education were significantly associated. Yoga and mindfulness meditation as promising complementary therapies for treating and preventing addictive behaviors [20]. The hypothetical models propose that the skills, perceptions, and self-awareness adapted through the practice of yoga and mindfulness can target multiple psychological, physiological, neural, and behavioral processes that maybe associated with relapse due to addiction [20].

Electronic Cigarettes

Also, electronic cigarettes are becoming popular and being debated concerning their role in smoking cessation. The electronic cigarettes are similarly known as e-cigarette, which is electronic nicotine delivery systems a mechanical device designed to mimic regular cigarettes, looks conventional alike cigarette, delivers nicotine through inhaling vapors without burning tobacco. These devices are supposed to deliver nicotine without any toxins considered to be a safer alternative to regular tobacco cigarettes. However, there are no sufficient studies to determine the vapors generates from e-cigarettes don't contain any toxic substances harmful to health in contrast to the natural tobacco smoking which has been proved to be carcinogenic. These electronic devices sold as a tobacco delivery device need to be regulated. Currently, there are no uniform regulations, either no regulations or at some places complete ban on sale. Countries like Canada, Mexico, Israel, Brazil, Hong Kong, Panama, Singapore and the United Arab Emirates have completely banned e-cigarettes [21].Subsequently, more practical approaches are needed to reduce the burden of cigarette smoking.

E-cigarettes were used much by former smokers to avoid relapse or as an aid to cut down or quit smoking as the second option to nicotine replacement medications. Based on e-cigarette literature review, it was found that electronic devices sold as a nicotine delivery device, need further research to gather scientific evidence of their safety, efficacy of device in delivering nicotine and other substances, patterns of use, effectiveness for smoking cessation or quitting, prevention of relapse, and issues associated regulations with the use of e-cigarettes. Many studies have shown that smoking e-cigarette is harmless compared to smoking traditional cigarettes. Most of the devices contain nicotine and inhaling their vapors exposes users to toxic substances, including lead, cadmium, and nickel, heavy metals that linked with significant health problems [22].

There are numerous unreciprocated questions about their comprehensive influence. For example; are e-cigarette used by young new non-smokers; would e-cigarettes be a gateway to tobacco use or nicotine dependency; is there any tendency for addiction to e-cigarettes or could its use in public places challenge smoke-free laws. The nicotine and other chemicals found in e-cigarettes might harm brain development in young persons and younger persons who start smoking are more likely to develop a habit and are more prone to addiction. Young persons who have never smoked or never tried smoking, when starts to use e-cigarette might get an addiction to nicotine and decide to switch to regular cigarettes is the biggest worry and public health concern, if the government does not ban e-cigarette sale to underage [23].

Smoking Cessation Policies and Interventions

Smoking cessation is vital to any tobacco control program. It is also one of the important modules of a widespread tobacco policy that strongly contributes to decreasing the smoking prevalence and thereby reduces tobacco-related morbidity and mortality. Numerous policies influence smokers' inspiration to quit smoking. The tobacco control measures such as increased taxation on tobacco and tobacco products, ban on advertising and promotion by global communications media, smoke-free areas and educational campaigns increase smokers’ motivation to stop. These policies also help in creating a climate that makes it easier for former smokers to remain abstained [24].

An international body of research indicates smoking cessation policies and interventions are cost-effective that include two comprehensive types of activities:

1) mass population policies and actions aimed to motivate smokers to quit smoking, such as higher prices through taxation, restrictions on smoking in public places and mass media educational campaigns, and

2) policies and activities designed to help dependent smokers who are already motivated to quit [25].

In May 2010, a committee of 20 experts from 12 countries on tobacco control, economics, epidemiology, and public health policy met at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (Frank, 2010). They discussed the series of evidence gathered after conducting studies on the tobacco pricing and tax related lobbying; tax, price and collective demand for tobacco; tax, price and adult tobacco use, use among adolescents and among poor; and impact of tobacco taxation on health. All the studies were conducted in both the developed and underdeveloped countries including high, medium and low income. From eighteen total studies, twelve study's conclusions were showing strength of the effectiveness on tax reduction and price increase. A small number of high-income group countries report that higher prices increased smoking cessation rate. Studies from countries of low, medium and high-income report that smoking among young people decreases as price increases. After consensus, the expert scientists’ committee concluded that there is sufficient evidence of effectiveness of increased tobacco excise taxes and prices in reducing the prevalence of tobacco use and improvement of public health (Frank, 2010).

Uruguay, a middle-income country in South America, implemented a comprehensive continued program of multiple tobacco control procedures consisting of a ban on publicity and promotion. Additionally, the ban on smoking in enclosed public spaces and workplaces, the policy for healthcare providers to treat nicotine dependence. Furthermore, a rule, that signs with warnings cover eighty percent of the front and back of every cigarette pack in addition to the ban on using misleading terms such as light and mild, besides a considerable increase in tobacco taxes. The results reported over during six years' period from 2005 to 2011 was about a 23% decrease in tobacco use [26].

According to a Global Youth Survey (GYT) from Bangladesh, a low-income country in Asia, report between 2007 and 2013, the use of tobacco and its products has not decreased. The rationale being no good smoking cessation programs and lack of resources and insufficient policies on tobacco control. This is despite many students (59.9%) expressing the desire to quit smoking if they have proper guidance and tools (World Health Organization, 2015).

Brazil, an upper middle-income country, being a third largest tobacco producing country in the world, has a comprehensive tobacco control policy including restrictions on publicity, ban on smoking in indoor public areas, mandatory pictorial warning labels on cigarette packs and total ban on menthol cigarettes, increase tax and pricing policies. One study showed that increase taxes and price rise have great potential to stimulate cessation and reduces prevalence among the vulnerable population [27-30].

Conclusion

This review suggests, the trends of smoking habits and smoking cessation intervention strategies differ from region to region when viewed from an international perspective. This highlights the necessity for the improvement of new methods that prevent people from starting to smoke, motivate to quit smoking and sustain long-term cessation. Further, we suggest exploring how to change more smokers to try quitting and to choose the most appropriate evidence-based practical approach and to try more frequently. If appropriate and applicable, poly pharmacotherapy should be offered for a prolonged period since relapse is more common. Cessation programs must be custom-made to focus on the envisioned audience rather than just providing information. It is observed by many that e-cigarette to be harmless than traditional cigarettes, still a lot of the devices contain nicotine and inhaling their vapors exposes users to toxic substances, including lead, cadmium, and nickel, heavy metals that linked with significant health problems [22]. In developing countries due to lack of infrastructure, and funds are the major drawback towards the success of smoking control and smoking cessation, rich countries should extend help in the implementation of intervention programs. Additionally, countries can also contribute by strictly implementing taxation on cigarettes and increase the price of tobacco and tobacco products in general. Future research should be directed to assess whether increasing the number of quitting attempts would positively impact smoking cessation.

References

- https://regulations.justia.com/regulations/fedreg/2014/04/29/2014-09615. html

- Hyland A, Borland R, Li Q, Yong HH, Neill MA, et al. (2006) Individual- level predictors of cessation behaviors among participants in the international tobacco control (ITC) four country survey. Tob Control 15(suppl_3): iii83-iii94.

- Murthy P, Saddichha S (2010) Tobacco cessation services in India: Recent developments and the need for expansion. Indian J Cancer 47(Suppl 1): 69-74.

- Ali R, Hay S (2017) Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 389(10082):1885- 1906.

- (2014) US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking-50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014.

- World Health Organization (2011) WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2011: Warning about the dangers of tobacco: Executive summary. Tobacco Free Initiative.

- Wegmann L, BUhler A, Strunk M, Lang P, Nowak D, et al. (2012) Smoking cessation with teenagers: the relationship between impulsivity, emotional problems, program retention and effectiveness. Addict Behav 37(4): 463-468.

- Trinidad DR, Perez-Stable EJ, Emery SL, White MM, Grana RA, et al. (2009) Intermittent and light daily smoking across racial/ethnic groups in the United States. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 11(2): 203-210.

- Stead LF, Perera R, Bullen C, Mant D, Hartmann-Boyce J, et al. (2012) Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 11: CD000146.

- (2016) WHO | Fact sheet about health benefits of smoking cessation.

- (2004) US Department of Health and Human Services 2004, The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General, US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2004.

- Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz N, et al. (2008) Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 Update. Rockville (MD): US Department of Health and Human Services.

- Gollust SE, Schroeder SA, Warner KE (2008) Helping smokers quit: understanding the barriers to utilization of smoking cessation services. Milbank Q 86(4): 601-627.

- Cami J, Farre M (2003) Drug addiction. N Engl J Med 349(10): 975-986.

- (2008) WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008 - The MPOWER package.

- Backinger CL, Fagan P, Matthews E, Grana R (2003) Adolescent and young adult tobacco prevention and cessation: current status and future directions. Tob Control 12(suppl 4): iv46-iv53.

- Strickland JR, Smock N, Casey C, Poor T, Kreuter MW, et al. (2015) Development of targeted messages to promote smoking cessation among construction trade workers. Health Educ Res 30(1): 107-120.

- Gorin SS, Heck JE (2004) Meta-analysis of the efficacy of tobacco counseling by health care providers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13(12): 2012-2022.

- Cummins SE, Bailey L, Campbell S, Koon-Kirby C, Zhu SH, et al. (2007) Tobacco cessation quitlines in North America: a descriptive study. Tob Control 16(Suppl 1): i9-i15.

- Sood A, Ebbert JO, Sood R, Stevens SR (2006) Complementary treatments for tobacco cessation: a survey. Nicotine Tob Res 8(6): 767-771.

- Lindsay (2013) Countries Where Vaping is Banned and Why e-cigarettes Reviewed.

- Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA (2014) E-cigarettes a scientific review. Circulation 129(19): 1972-1986.

- Etter JF, Bullen C (2011) Electronic cigarette: users profile, utilization, satisfaction, and perceived efficacy. Addiction 106(11): 2017-2028.

- World Health Organization (2004) WHO European strategy for smoking cessation policy

- Fronczak A, Polanska K, Usidame B, Kaleta D (2012) Comprehensive tobacco control measures-the overview of the strategies recommended by WHO. Cent Eur J Public Health 20(1): 81-86.

- Abascal W, Esteves E, Goja B, Mora FG, Lorenzo A, et al. (2012) Tobacco control campaign in Uruguay: a population-based trend analysis. The Lancet 380(9853): 1575-1582.

- Gigliotti A, Figueiredo VC, Madruga CS, Marques AC, Pinsky I, et al. (2014) How smokers may react to cigarette taxes and price increases in Brazil: data from a national survey. BMC public health 14(1): 327.

- (2017) Cdc.gov-Morbidity and mortality weekly report 201; 61(31): 581.

- Chaloupka F, Straif K, Leon ME. Working Group, International Agency for Research on Cancer (2011) Effectiveness of tax and price policiesin tobacco control. Tob Control 20(3): 235-238.

- Warner KE, Mackay JL (2008) Smoking cessation treatment in a public health context. Lancet 371(9629): 1976-1978.

© 2018 Sarvath Ali. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)