- Submissions

Full Text

Research & Development in Material Science

Investigation on Peritectic Layered Structures by Using the Binary Organic Components TRIS-NPG as Model Substances for Metal-Like Solidification

JP Mogeritsch* and A Ludwig

Department of Metallurgy, Montanuniversitaet Leoben, Austria

*Corresponding author: JP Mogeritsch, Department of Metallurgy, Chair for Simulation and Modelling Metallurgical Processes, Montanuniversitaet Leoben, Austria

Submission: February 09, 2018; Published: February 26, 2018

Volume 4 Issue 1 February 2018

Abstract

This communication gives a short overview about the latest research findings in the field of peritectic solidification pattern formation by using transparent organic components as model substances. These materials solidify metal-like and thus enable in-situ observations of the solidification dynamics with a simple transmitted-light microscope. Peritectic solidification pattern are strongly affected by thermo-solutal convection. Hence, experiments were carried out to analyze the effect convection does have on the formation of, in particular, layered peritectic solidification structures. In future, μg experiments aboard the International Space Station (ISS) are foreseen where natural convection is omitted.

Keywords: Layered structures; Organic substances; Peritectic reaction; Convection; Solidification; ISS; Bridgman-furnace; Direct solidification; Organic substances

Introduction

Peritectic alloys are widely used and have high economic importance. Examples of this class of material are steels, aluminum and copper alloys, rare earth magnets and composites. As the material properties are directly related to their solidification microstructures, a deeper understanding of the peritectic growth process is critical for getting an optimized quality of these alloys.

A peritectic reaction is the transformation of a liquid and an already existing primary solid phase a to a second solid peritectic phase P(L +a^P). In the case where both solid phases occur in a dendritic manner the second phase solidifies directly from the liquid as well as by transforming from the primary solid phase. Under condition where the solidification morphology for one or both phases is planar, a peritectic alloy shows a variety of complex microstructures like isothermal peritectic coupled growth (IPCG), cellular peritectic coupled growth, discrete bands, island bands, or oscillatory tree-like structures.

The theory and the conditions for possible band formations in peritectic systems without convection are described by Trivedi [1]. Since the formation of these solidification microstructures is sensitive to convection (which is nearly always present under gravity conditions) the observed solidification behavior is not well understood. To deepen the understanding of the formation of such complex peritectic structures the authors observed the dynamic of layered structure formation by using organic components [2-7] instead of metals [8-27]. Experiments were carried out by affected knowingly the freedom of convection during the solidification. Additionally, comparative experiments are going on to be carried out under |ig conditions aboard the International Space Station (ISS). By doing this, the influence of the natural convection on this particular peritectic solidification structures can be determined.

Research Method

Till today, only few organic systems were found that are suitable for the use as peritectic model system. It requires an appropriate concentration and temperature range for the peritectic region and both solid phases must show a non-facetted high temperature phase. The selected transparent organic model system TRIS (Tris- hydroxymenthyl-aminomethane)-NPG (Neopentylglycol) was analyzed by Barrio et al. [28]. It shows a peritectic region within the range of 0.47 to 0.54w% at the peritectic temperature of 410.7K.

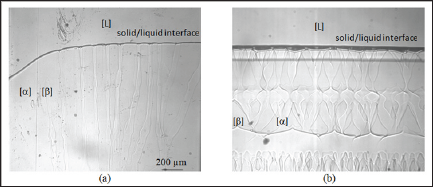

To affect the freedom of convections, peritectic concentrations were filled in rectangular glass tube samples, either with an inner width of 100|im (near 2D) or of 600|im (more 3D). To control the process conditions, the samples are pulled through a selfconstructed micro Bridgman-furnace. This enables to specified and adjusted the temperature gradient and the solidification rate. The microscope was equipped with a CCD camera which allows taking and store time lapsed movies for a later evaluation of the experiments. The dark spots in both images and also the noticeable structure in the upper left area of the left image are contaminants on the outer glass surface. The gray lines represent the interface between the solid phases and the liquid, respectively.

Results and Discussions

An example of the result of our investigations can be seen in Figure 1. Both pictures show an isothermal peritectic coupled growth (IPCG) structure. The interface between solid and liquid can be recognized by the lateral horizontal dark gray line. The interface between the two solid phases (primary α phase and the peritectic β phase) appear in various dark grey tones depending on the depth within the sample. The growth morphologies of the IPCG are significant different in shape and growth dynamic. In 2D samples were the lamella spacing is in the same order of magnitude than the width of the sample, 3D growth features are almost suppressed. Therefore, the lamellae grow very straight in the vertical direction. In contrast, within a 3D samples, where the lamella spacing is less than the width of the sample, three-dimensional competition growth in lateral and transversal directions leads to partial bands and tulip-like oscillating lamellae.

Figure 1: Isothermal peritectic coupled growth observed by using a glass sample with an inner width of 100μm (a) and one with an inner width of 600μm (b). The difference is obvious.

Conclusion

For the first time, the formation of layered peritectic structures has been observed in real time by using model substances. The results show how the development of the microstructure is influenced by the competition between growth and existing convection. The future investigations under ng conditions aboard the ISS (and thus with absents of natural convection) will further deepen our understanding of the impact convection might have on the formation of peritectic layered structures.

Acknowledgement

This research has been supported by the Austrian Research promotion Agency (FFG) in the frame of the METTRANS project and by the European Space Agency (ESA) in the frame of the METCOMP project.

References

- Trivedi R (1995) Theory of layered-structure formation in peritectic systems. Metall Mater Trans 26(6): 1583-1590.

- Ludwig A, Mogeritsch J (2011) In-situ observation of coupled peritectic growth. In: Solidif Sci Technol Proc John Hunt Int Symp, pp. 233-242.

- Mogeritsch J, Ludwig A (2011) In-situ observation of coupled growth morphologies in organic peritectics. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 7: 12028.

- Mogeritsch J, Ludwig A (2012) Microstructure formation in the two phase region of the binary peritectic organic system TRIS-NPG. In: TMS Annual Meeting Symposium, Materials Res Microgravity, Orlando, Florida, USA, pp. 48-56.

- Ludwig A, Mogeritsch J (2014) Recurring instability of cellular growth in a near peritectic transparent NPG-TRIS alloy system. Mater Sci Forum, pp. 317-322.

- Mogeritsch J, Ludwig A (2015) In-situ observation of the dynamic of peritectic coupled growth using the binary organic system TRIS-NPG. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 84: 12055.

- Ludwig A, Mogeritsch J (2016) Compact seaweed growth of peritectic phase on confined, flat pro-peritectic dendrites. Journal of Crystal Growth 455: 99-104.

- Titchener AP, Spittle JA (1975) The microstructures of directionally solidified alloys that undergo a peritectic transformation. Acta Mater 23(4): 497-502.

- Busse P, Meissen F (1997) Coupled growth of the properitectic α-and the peritectic γ-phases in binary titanium aluminides. Scr Mater 37: 653658.

- Lee JH, Verhoeven JD (1994) Peritectic formation in the Ni-Al system. J Cryst Growth 144(3-4): 353-366.

- Vandyoussefi M, Kerr HW, Kurz W (1997) Directional solidification and δ/γ solid state transformation in Fe 3% Ni alloy. Acta Mater 45(10): 4093-4105.

- Li Y, Ng SC, Jones H (1998) Observation of lamellar eutectic-like structure in a Zn-rich Zn-3.37wt% Cu peritectic alloy processed by Bridgman solidification. Scr Mater 39n: 7-11.

- Ma D, Li Y, Ng SC, Jones H (2000) Unidirectional solidification of Zn- rich Zn-Cu peritectic alloys-II. Microstructural length scales. Acta Mater 48(8): 1741-1751.

- Vandyoussefi M, Kerr HW, Kurz W (2000) Two-phase growth in peritectic Fe-Ni alloys. Acta Mater 48(9): 2297-2306.

- Ma D, Li Y, Ng SC, Jones H (2000) Unidirectional solidification of Zn-rich Zn-Cu peritectic alloys-I Microstructure selection. Acta Mater 48(2): 419-431.

- Sumida M (2003) Evolution of two phase microstructure in peritectic Fe-Ni alloy. J Alloy Compd 349(1-2): 302-310.

- Lo TS, Dobler S, Plapp M, Karma A, Kurz W (2003) Two-phase microstructure selection in peritectic solidification: from island banding to coupled growth. Acta Mater 51(3): 599-611.

- Dobler S, Lo TS, Plapp M, Karma A, Kurz W (2004) Peritectic coupled growth. Acta Mater 52(9): 2795-2808.

- Su YQ, Liu C, Li XZ, Guo JJ, Li BS, et al. (2005) Microstructure selection during the directionally peritectic solidification of Ti-Al binary system. Intermetallics 13(3-4): 267-274.

- Su YQ, Luo LS, Li XZ, Guo JJ, Yang HM, Fu HZ (2006) Well-aligned in-situ composites in directionally solidified Fe-Ni peritectic system. Appl Phys Lett 89: 2319181-2319183.

- Luo LS, Su YQ, Guo JJ, Li XZ, Fu HZ (2007) A simple model for lamellar peritectic coupled growth with peritectic reaction. Sci China Phys Mech Astron 50: 442-450.

- Hu XW, Li SM, Liu L, Fu HZ (2008) Microstructures evolution of directionally solidified Sn-16%Sb hyperperitectic alloy. China Foundry 5: 167-171.

- Luo W, Shen J, Min Z, Fu H (2008) Lamellar orientation control of TiAl alloys under high temperature gradient with a Ti-43Al-3Si seed. J Cryst Growth 310(24): 5441-5446.

- Luo LS, Su YQ, Guo JJ, Li XZ, Li SM, et al. (2008) Peritectic reaction and its influences on the microstructures evolution during directional solidification of Fe-Ni alloys. J Alloy Compd 461(1-2): 121-127.

- Luo LS, Su YQ, Li XZ, Guo JJ, Yang HM, et al. (2008) Producing well aligned in situ composites in peritectic systems by directional solidification. Appl Phys Lett 92: 61903.

- Zhong H, Li SM, Lü HY, Liu L, Zou GR, et al. (2008) Microstructure evolution of peritectic Nd14Fe79B7 alloy during directional solidification. J Cryst Growth 310(14): 3366-3371.

- Feng ZR, Shen J, Min ZX, Wang LS, Fu HZ (2010) Two phases separate growth in directionally solidified Fe-4.2Ni alloy. Mater Lett 64(16): 1813-1815.

- Barrio M, Lopez DO, Tamarit JL, Negrier P, Haget YJ (1995) Degree of miscibility between non-isomorphous plastic phases: binary system NPG-TRIS. Mater Chem 5(3): 431-439.

© 2018 JP Mogeritsch, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)