- Submissions

Full Text

Orthopedic Research Online Journal

Abdominal Pain Caused by Bilateral Acetabular Fractures Secondary to an Epileptic Seizure Case Report and Review of the Literature

RWPM Geerts1, L Verlaa1, JJ Arts2, PBJ Tilman1 and EJP Jansen1

1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Orbis Medisch Centrum, The Netherlands

2Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Maastricht University Medical Centre, The Netherlands

*Corresponding author: EJP Jansen, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Orbis Medisch Centrum, Dr. H van der Hoffplein1, 6162 BG, Sittard-Geleen, The Netherlands

Submission: October 01, 2017; Published: October 31, 2017

ISSN : 2576-8875Volume1 Issue2

Abstract

Background: Epileptic patients have increased risk of fractures. This is related to the traumatic event itself and to concomitant factors. Clear fracture related complaints are not always present at primary survey of these patients. This indicates a thorough primary evaluation of the complete individual post-seizure. We present a unique case of abdominal pain due to bilateral acetabular fracture after an epileptic seizure.

Case Report: A 66-year old patient, who chose to live solitary and was in suboptimal hygienic condition, was admitted to the neurological department after two epileptic seizures. Three days after admission, an abdominal radiograph revealed bilateral acetabular and pubic fractures as chance findings. Treatment was challenging due to patient and fracture specific conditions. Conservative treatment options were limited and eventually failed. Eventually, bilateral total hip prosthesis with bone impaction grafting were performed. At one-year follow up, no restriction in active daily living was noted.

Conclusion: Seizure induced bilaterally acetabular fractures are very rare. Thorough physical examination after an epileptic seizure is imperative to identify fractures. Abdominal pain can be the only symptom of a fractured acetabulum. Treatment options are dependent of patient’s morbidity, bone quality and surgeon’s preference. Primary total hip arthroplasty might be indicated and can offer good results even in case of bilateral acetabular fractures.

Keywords: Seizure; Bilateral; Acetabulum; Fracture; Abdominal; Treatment; Conservative; Surgical; Prosthesis; Osteoporosis; Case; Literature; Review

Introduction

Patients with epilepsy have increased fracture risks [1-3]. These fractures can be related to the seizure itself but 40% are associated with osteopenia [4,5]. Osteopenia may occur as a result of physical impairment, a postmenopausal state, or can be induced by antiepileptic drugs [6]. Thorough secondary survey for fractures after seizures is therefore essential especially when osteoporosis is present.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a patient in whom abdominal pain was the only complaint due to bilateral acetabular fractures caused by epileptic seizures. Besides, the literature is reviewed and treatment options are suggested.

Case Report

A 66-year old female was admitted to the neurological ward after two epileptic seizures. Her medical history consisted of hypothyroidism, chronic hyponatraemia, anaemia, and a lumbar vertebral fracture (L1) after an epileptic seizure 5 years earlier. She suffered from poor mobility due to chronic back pain and lived in social isolation. Traumatic injuries were not diagnosed during primary evaluation at the emergency department. She was admitted for neurological observation. Morbus Hashimoto and a Hashimoto-encephalopathy (steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with auto-immune thyroiditis) were diagnosed during the first days. Her laboratory results showed a small drop in serum hemoglobin one day after admission (8.9mmol/L and 8.4mmol/L on day 0 and day 1, respectively). During mobilization she complained of persevering abdominal pain. Three days after admission, an abdominal radiograph revealed bilateral acetabular and pubic fractures as chance findings.

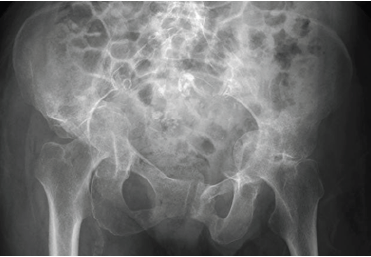

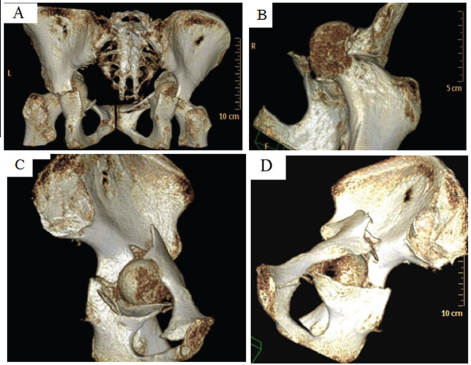

Further radiographic (Figure 1) and computed tomographic (CT, Figure 2) pelvic analysis revealed multi-fragmented acetabular fractures with protrusion of both femoral heads through the quadrilateral plate (Müller AO classification: 62-C2; Letournel Classification: complex type, transverse fracture with posterior wall fracture [7]. Moreover, an impaction fracture in the superior lateral aspect of the left femoral head was shown together with fractures of both superior pubic ramus and the left inferior pubic ramus.

Figure 1: Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis showing protrusion of both femoral heads and bilateral fractures of the superior pubic ramus.

Figure 2: 3-D CT reconstruction of the pelvis showing (A) posterior view of protrusion of both femoral heads through the quadrilateral plates and right superior pubic ramus fracture; (B) anterior view of left femoral head impaction fracture; (C) medial view of left femoral head protrusion, superior pubic ramus and anterior column fracture; (D) posteromedial view of right acetabulum showing superior pubic ramus and quadrilateral plate fracture.

Considering the patient’s poor personal hygiene and social conditions, our suggested primary treatment was femoral pin traction for six weeks in order to realign the protrusion of both femoral heads. This treatment was refused and therefore nonweight- bearing mobilization was started. However, after three months the abdominal pain still persisted together with non-union of the acetabula with radiological evaluation.

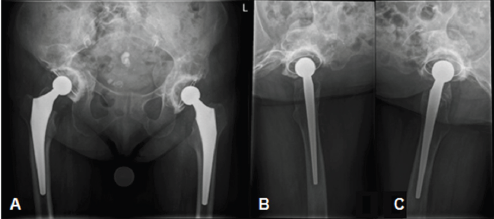

Bilateral hybrid total hip arthroplasties with bone impaction grafting were performed three and four and a half months postadmittance (left and right side, respectively). The central acetabular defects were closed using autograft material from both femoral heads. In this manner, a solid alternative quadrilateral plate was realised and no metal meshes before bone impaction grafting were required. Cemented acetabulum components (Contemporary® (Stryker Orthopaedics, Kalamazoo, Michigan, U.S.A.)), with ceramic Biolox® Delta femoral heads (Stryker) (size 28mm) and Accolade® uncemented hydroxyapatite (HA) coated hip stems (Stryker) were used (Figure 3). Postoperatively, full-weight-bearing mobilisation with two crutches was allowed. Two months postoperatively, the patient experienced no pain. At six months follow-up, she was able to walk small distances without help. At one-year follow up, no restriction in active daily living was noted.

Figure 3: Radiographs of pelvis and both hips at 1 year follow-up showing (A) anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis with bilateral total hip prostheses; (B) lateral view of left total hip arthroplasty; (C) lateral view of right total hip arthroplasty.

Discussion

In this case study, we present a patient with epileptic seizure induced bilateral acetabular fractures with protrusion of both hips. It is noteworthy that these fractures were discovered three days after admission as chance findings. Physicians must be aware that patients have an increased fracture risk after an epileptic insult, especially elderly and osteoporotic patients. Seizure induced acetabular fractures, especially bilateral acetabular fractures, are scarcely reported. A review of literature identified 27 cases of seizure related acetabular fracture-dislocations, of which only 10 were bilateral [1,3,8-11]. All of these patients complained of groin pain [1,3], in contrast to our patient who suffered from abdominal pain.

Acetabular fractures are usually caused by high energetic trauma especially to the trochanter region, e.g. car/motor accidents and fall from heights [1,3,10]. In epileptic patients, the tremendous mass of pelvitrochanteric muscle contracts forcefully in a craniomedial direction during a seizure, which can result in a fracture dislocation [1,10]. Epileptic seizures are associated with a general fracture risk of 0.25% to 2.4% [3,10,12,13], which is 2-6 times the fracture rate in the general population [14]. In 40% of epileptic patients the fracture is associated with osteopenia, which is either due to physical impairment, postmenopausal state, or related to anti-epileptic drugs (AED) [4,5].

Both enzyme inducing- and nonenzyme inducing AEDs affect bone quality. Enzyme inducing AEDs (e.g. carbamazepine, phenytoin and phenobarbital) alter vitamin D concentrations and may lead to reduced bone mass. Nonenzyme inducing AEDs (e.g. benzodiazepines, gabapentin and levetiracetam) affect bone by altering osteoblastic function, may affect intestinal calcium absorption and can induce anticonvulsant osteopathy [15-17]. Our patient did not use any AEDs. Hence, osteopenia or osteoporosis seems to be an important contributing factor to the fractures in our patient. The previous L1 fracture, poor overall mobility, bilateral nature of the incident fractures, post-menopausal state and the general osteopenic impression on plain radiographs all hint towards osteopenia or osteoporosis.

Overall, 30-35% of patients with seizures have experienced secondary injuries (e.g. fractures, contusions, skin lesions) during lifetime. Desai et al [18]. Reported that the most common fractures in epileptic patients were intertrochanteric femoral fractures, femoral neck fractures, ankle fractures and proximal humeral fractures. Acetabular, pelvic or other femoral fractures are less common but should be considered when patients complain of pain to the pelvis, the groin, or as presented in this case study, even the abdomen. Un explained low blood hemoglobin should also increase suspicion of a fracture. In general, mortality rate of major bleeding due to pelvic fractures induced by an epileptic insult is 18.5%. Thus, careful attention must be paid to patients with this conditions [1,10,19]. These findings support the relevance of performing a thorough secondary evaluation in seizure patients [3]. Long-term consequences of acetabular fractures can include avascular necrosis of the femoral head (2% to 40%), degenerative osteoarthritis (12% to 57%) or both [7,20,21].

Treatment options for acetabulum fractures, especially in the presence of osteoporosis, depend mainly on fracture type and comorbidities. They include conservative methods, open reduction and fixation, and total hip arthroplasty [22]. Conservative treatment is the most suitable option in case of a non-displaced acetabular fracture. Non-surgical treatment can also be considered in dislocated acetabular fractures with anterior column involvement or in intrinsically stable injuries such as transverse type fractures [22-25]. Complications of conservative treatment or minimally invasive procedures (e.g. traction or external fixation) include amyotrophy, pressure ulcers, deep venous thrombosis, pin tract infection and increased mortality. Most importantly, the likelihood of attaining an acceptable acetabular reduction by traction alone is small [1,7,10,19,20,22,23,25-27].

Preferred treatment in most cases of displaced acetabular fractures is open reduction and internal fixation. However, prognosis for some injury patterns is poor, especially in case of osteoporotic bone. Femoral head resection, which enables elderly patients to continue their normal daily living within acceptable time limits, may be preferable in some cases.

Total hip arthroplasty should be considered when there is intra-articular comminution, full thickness abrasive loss of articular cartilage, impaction of the femoral head, impaction of the acetabulum that involves more than forty percent of the joint surface, or failure of conservative treatment. In presence of osteoporosis and comminution, total hip arthroplasty has hardly been performed due to difficulties in attaining sufficient acetabular fracture stabilisation required for adequate cup fixation [28]. In case of healed displaced acetabular fractures, delayed total hip arthroplasty is even more challenging due to acetabular deformity and the lack of acetabular bone stock [20,21,23]. Functional outcome after total hip arthroplasty in case of acetabular fractures is acceptable but influenced by age. Mears & Velyvis [29] reported on 57 primary total hip arthroplasties in unilateral displaced acetabular fractures with a mean patient age of 69 years at surgery. After a mean follow-up of 8.1 years, the authors reported a mean Harris Hip Score of 89 points. Seventy-nine percent of patients had an excellent or good outcome. Advancing age was associated with a progressive decrease in scores while younger patients had the highest scores [30-40].

In most displaced acetabular fractures open reduction and internal fixation is indicated. However, in case of osteoporotic bone prognosis can be poor and femoral head resection should be considered especially in frail elderly.

Total hip arthroplasty can be successfully performed in case of acetabular fractures in osteoarthritic hips; displaced acetabular fractures; or a significant impaction fracture of the femoral head.

Considering our patient’s characteristics, type of acetabular fracture, as well as the bilateral femoral head protrusion, femoral pin traction was suggested. This treatment was refused and nonweight- bearing was advised. Due to non-compliance, our patient still perceived substantial disabling pain. CT scans (three months post-seizure) revealed non-union of the posterior column of the right and anterior column of the left acetabulum. Bilateral reverse hybrid total hip arthroplasty with an acetabular repair using autografts was successfully performed. The next day, full-weightbearing mobilization was started. No complications were noted during follow-up and six months later she was able to walk small distances without any helping device. At one-year follow up, no limitations in daily life were noted [41-43].

Conclusion

Seizure induced bilaterally acetabular fractures are very rare. Thorough physical examination after an epileptic seizure is imperative to identify fractures. Abdominal pain can be the only symptom of a fractured acetabulum. Treatment options are dependent of patient’s morbidity, bone quality and surgeon’s preference. Treatment with primary total hip arthroplasty might be indicated and can offer good results even in case of bilateral acetabular fractures.

Disclosures

There were no benefits received in any form from a commercial party related to the products in the report.

References

- Takahashi Y, Ohnishi H, Oda K, Nakamura T (2007) Bilateral acetabular fractures secondary to a seizure attack caused by antibiotic medicine. Takahashe J Orthop Sci 12: 308-310.

- Ach K, Slim I, Ajmi ST, Chaieb MC, Beizig AM, et al. (2010) Non-traumatic fractures following seizures: two case reports. Cases J 3: 30.

- Friedberg R, Buras J (2005) Bilateral acetabular fractures associated with a seizure: a case report. Ann Emerg Med 46(3): 260-262.

- Vestergaard P, Tigaran S, Rejnmark L, Tigaran C, Dam M, et al. (1999) Fracture risk is increased in epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand 99(5): 269-275.

- Sheth RD, Harden CL (2007) Screening for bone health in epilepsy. Epilepsia 48(Suppl 9): 39-41.

- Harden CL (2003) Menopause and bone density issues for women with epilepsy. Neurology 61(6): S16-S22.

- Letournel E (1980) Acetabulum fractures: classification and management. Clin Orthop Relat Res 151: 81-106.

- Van Heest A, Vorlicky L, Thompson RC (1996) Bilateral Central Acetabular Fracture Dislocations Secondary to Sustained Myoclonus. Clin Orthop Relat Res 324: 210-213.

- Granhed HP, Karladani A (1997) Bilateral acetabular fracture as a result of epileptic seizure: a report of two cases. Injury 28(1): 65-68.

- Nehme AH, Matta, JF, Boughannam AG, Jabbour FC, Imad J, et al. (2012) Literature review and clinical presentation of bilateral acetabular fractures secondary to seizure attacks. Case Reports in Orthopedics 2012: Article ID 240838.

- Varma AN, Seth SK, Verma M (1-981) Simultaneous bilateral central dislocation of the hip- an unusual complication of eclampsie. Journal of Trauma 21(6): 499-500.

- Finelli PF, Cardi JK (1989) Seizure as a cause of fracture. Neurology 39(6): 858-860.

- Kelly JP (1954) Fractures complicating electro-convulsive therapy and chronic epilepsy. J Bone Joint Surg 36(1): 70-79.

- Souverein PC, Webb DJ, Petri H, Weil J, Van S, et al. (2005) Incidence of fractures among epilepsy patients. Epilepsia 46(2): 304-310.

- Pack AM, Morrell MJ, Marcus R, Holloway L, Flaster E, et al. (2005) Bone mass and turnover in epileptic women on antiepileptic drug monotherapy. Ann eurol 57(2): 252-257.

- Sheth RD (2004) Metabolic concerns associated with antiepileptic medications. Neurology 63: S24-29.

- Mosekilde L, Hansen HH, Christensen MS, Lund B, Sorenson OH, et al. (1979) Fractional intestinal calcium absorption in epileptics on anticonvulsant therapy. Acta Med Scan 205(1-6): 405-409.

- Desai KB, Ribbans WJ, Taylor GJ (1996) Incidence of five common fracture types in an institutional epileptic population. Injury 27(2): 97- 100.

- Hughes CA, O’Briain DS (2000) Sudden Death From Pelvic Hemorrhage After Bilateral Central Fracture Dislocations of the Hip Due to an Epileptic Seizure. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 21(4): 380-384.

- Coventry MB (1974) The treatment of fracture dislocation of the hip by total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg AM 56(6): 1128-1134.

- Romness DW, Lewallen DG (1990) Total hip replacement after fracture of the acetablum. Long term results. J Bone Joint Surg Br 72(5): 761-764.

- Vanderschot P (2007) Treatment options of pelvic and acetabular fractures in patients with osteoporotic bone. Int J Care Injured 38(4): 497-508.

- Matta JM, Merritt PO (1988) Displaced acetabular fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 230: 83-97.

- Pennal GF, Davidson J, Garside H, Plewes J (1980) Results of treatment of acetabular fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Re 151: 115-123.

- Hanschen M, Pesch S, Huber-Wagner S, Biberthaler P, et al. (1989) Acetabular fractures in older patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br 71: 774-776.

- Harper CM, Lyles YM (1998) Physiology and complications of bed rest. J Am Geriatr Soc 36(11): 1047-1054.

- Lowe LW (1981) Venous Thrombosis and embolism. J Bone Joint Surg Br 63-B: 155-167.

- Rossvoll I, Finsen V (1989) Mortality after pelvic fractures in the elderly. J Orthop Trauma 3: 115-117.

- Jimenez ML, Tile M, Schenk RS Total hip replacement after acetabular fracture. Orthop Clin North Am 28: 435-446.

- Mears DC, Velyvis JH (2002) Acute total hip arthroplasty for selected displaced acetabular fractures: 2-12 year results. J Bone Joint Surg Am 84-A: 1-9.

- Annegers JF, Melton LJ, Sun CA, Hauser WA (1989) Risk of age related fractures in patients with unprovoked seizures. Epilepsia 30(3): 348- 355.

- Duus BR (1986) Fractures caused by epileptic seizures and epileptic osteomalacia. Injury 17(1): 31-33.

- Hawkins RJ, Neer CS, Pianta RM, Mendoza FX (1987) Locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg 69(1): 9-18.

- Vernay D, Dubost JJ, Dordain G, Sauvezie B (1990) Seizures and compression fractures. Neurology 40(4): 725-726.

- Kirby S, Sadler RM (1995) Injury and death as a result of seizures. Epilepsia 36(1): 25-28.

- Nakken KO, Lossius R (1993) Seizure-related injuries in multihandicapped patients with therapy resistant epilepsy. Epilepsia 34(5): 836-840.

- Granhed H, Goteborgs U, Goteborg T (1998) Changes with age in bone mineral of the spine in normal men. Extreme Spine loadings. Effects on the vertebral bone mineral content and strength and the risk for future low back pain. P. 29.

- Hansson T, Roos B (1980) The influence of age, height and weight on the bone mineral content of lumbar vertebrae. Spine 5: 545-551.

- Krølner B, Pors Nielsen S (1982) Bone mineral content of the lumbar spine in normal and osteoporotic woman: cross sectional and longitudinal studies. Clin Sci (Lond) 62(3): 329-336.

- Chrischilles E, Shireman T, Wallace R (1994) Costs and health effects of osteoporotic fractures. Bone 15(4): 377-386.

- Goettsch WG, de Jong RB, Kramarz P, Herings RM (2007) Development of the incidence of osteoporosis in The Netherlands; a PHARMO study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 16(2): 166-172.

- Goettsch WG, de Jong RB, Kramarz P, Herings RM (2007) Development of the incidence of osteoporosis in The Netherlands; a PHARMO study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 16(2): 166-172.

- Mears DC, Shirahama M (1998) Stabilization of an acetabular fracture with cables for acute total hip arhtroplasty. J Arthroplasty 13(1): 104- 107.

© 2017 RWPM Geerts, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)