- Submissions

Full Text

Open Journal of Cardiology & Heart Diseases

Contemporary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction and Left Main Culprit Lesions: A Report from the NCDR®

Gilbert J Zoghbi1, Vijay K Misra2, Brigitta C Brott2, Silvio E Papapietro2, David Dai3, Tracy Y Wang3, Lloyd W Klein4 John C Messenger5 and William B Hillegass2*

1Stern Cardiovascular Foundation, USA

2University of Alabama at Birmingham, USA

3Duke Clinical Research Institute, USA

4Rush University Medical Center, USA

5University of Colorado, USA

*Corresponding author: William B Hillegass, Division of Cardiovascular Disease and Department of Biostatistics, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 2145 Bonner Way, Birmingham, AL 35243, USA

Submission: February 09, 2018; Published: February 26, 2018

ISSN: 2578-0204 Volume1 Issue3

Abstract

Background: The characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of PCI for LM AMI have not been studied in a large patient population

Objectives: To describe the incidence, characteristics, in-hospital outcomes and prognostic determinants of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) due to unprotected left main coronary artery UPLMCA lesions.

Methods: The characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of PCI for LM AMI were studied in the CathPCI Registry® between 2004 and 2008.

Results: 434 patients underwent PCI for ST elevation MI (STEMI) and 387 patients underwent PCI for Non STEMI due UPLMCA lesions. Cardiogenic shock and class 4 NYHA were present in 66.4% and 74.9% of patients with STEMI respectively compared with 31.9% and 51.7% of patients with NSTEMI. The in-hospital mortality rate was 58% in the UPLMCA STEMI patients and 28% in the UPLMCA NSTEMI patients compared to 19% in a cohort of 116 patients with protected LMCA (PLMCA) STEMI and 6% in a cohort of 610 patients with PLMCA NSTEMI PCIs. Significant variables associated with in-hospital mortality were age/10 years increase (odds ratio [OR]=1.2; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.02-1.4), primary PCI (OR=0.6; CI: 0.4-0.97), GFR/10 unit increase (0R=0.9; CI: 0.8-0.97), UPLMCA NSTEMI (OR=2.6; CI: 1.5-4.2), UPLMCA STEMI (0R=5.0; CI: 3.0-8.4), cardiogenic shock (OR=7.5; CI: 5.2-10.8), pre PCI IABP placement (OR=2.3; CI: 1.1-4.7), salvage PCI (OR=4.3; CI: 2.3-8.1), and pre PCI TIMI flow 0/1 (OR=2.3; CI: 1.6-3.3).

Conclusion: PCI for UPLMCA AMI carries a very high in-hospital mortality rate, particularly in patients presenting with STEMI and cardiogenic shock.

Keywords: PCI; Acute myocardial infarction; Left main

Introduction

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of unprotected left main coronary artery (UPLMCA) is considered a class IIa indication in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) with less than TIMI-3 flow and PCI can be performed more rapidly and safely than coronary bypass surgery (CABG). In unstable angina/ NSTEMI patients with left main culprit lesion, PCI is class IIa if the patient is not a candidate for CABG [1]. Contemporary studies have shown favorable short and long term outcomes of UPLMCA PCI with comparable mortality, myocardial infarction (MI), or stroke rates to coronary bypass grafting (CABG) and a higher rate of repeat revascularization [2-4]. However, most of these studies included stable patients and excluded patients with acute MI (AMI).

Acute LMCA occlusion is a rare and catastrophic event. Its incidence, clinical features, outcomes, and prognostic determinants have been reported in few and small single center series of consecutive patients [5-8] and in one multicenter registry of LMCA PCI [9]. The incidence of AMI due to LMCA obstruction ranges between 0.8% to 2.4% [5,7,8]. AMI due UPLMCA, particularly ST elevation MI (STEMI), was associated with cardiogenic shock in up to 80% of patients, pulmonary edema in up to 95% of patients, respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilatory support in up to 90% of patients and an in-hospital mortality rate that approached 65% [5-18].

We studied the incidence, clinical and angiographic features, inhospital outcomes and prognostic determinants of contemporary PCI for STEMI due to UPLMCA lesions from a large cohort of patients enrolled in the CathPCI Registry. The characteristics and outcomes of these patients were compared to those who underwent PCI for STEMI due to protected LMCA (PLMCA) and for non STEMI due to PLMCA and UPLMCA.

Methods

The CathPCI Registry® database

The CathPCI Registry is a national quality improvement program with a goal of measuring and improving the care of patients undergoing PCI. The registry is an initiative of the American College of Cardiology Foundation and The Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Details of data collection procedures and quality control measures have been previously described [19]. Data are abstracted from patient medical records and catheterization laboratory reports by trained data managers at each participating facility, and submitted quarterly to the central data facility. Data elements include patient demographics, medications administered in hospital, medical history and comorbidity, clinical characteristics at admission, coronary anatomy, lesion characteristics, procedural characteristics, adverse outcomes, and discharge status and medications (https ://www. ncdr.com/webncdr/DefaultCathPCI.aspx).

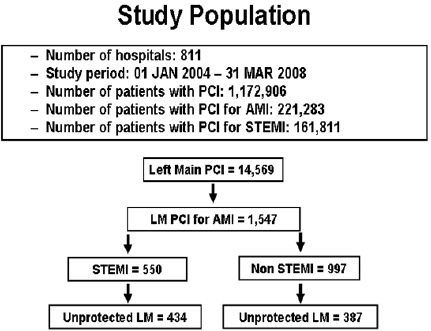

Patient population

The patient population was derived from the subset of patients in the CathPCI Registry who underwent PCI for AMI due to a LMCA lesion between 1/04 and 3/08 at 811 US hospitals (Figure 1). The patient population of LMCA culprit lesions was divided into 4 groups: STEMI from UPLMCA, NSTEMI from UPLMCA, STEMI from PLMCA, and NSTEMI from PLMCA. For practical reasons, patients who had a prior CABG were categorized as having a PLMCA.

Figure 1: The Derivation of the Patient Population from the CathPCI Registry.

AMI: Acute Myocardial Infarction; LM: Left Main; NSTEMI: Non ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction;

STEMI: ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed by the Duke Clinical Research Institute that serves as the primary analytic center for the CathPCI Registry. Categorical variables are reported as % and continuous variables are reported as mean±standard deviation (SD). The Pearson chi-square test was used for all categorical variables and the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for continuous variables. The univariate and multivariate independent factors associated with inhospital mortality were determined. Logistic regression modeling with generalized estimating equations was used to develop the multivariable model examining factors significantly associated with mortality. Patients were excluded from the in-hospital outcomes analysis if they were transferred out from the hospital participating in the CathPCI Registry.

Results

Prevalence of PCI for LM AMI

The prevalence of PCI of UPLMCA STEMI was 0.037% among all index PCIs, 0.19% among PCIs for AMI and 0.27% among PCIs for STEMI. The prevalence of PCI of UPLMCA NSTEMI was 0.032% among all index PCIs, 0.17% among PCIs for AMI and 0.65% among PCIs for NSTEMI.

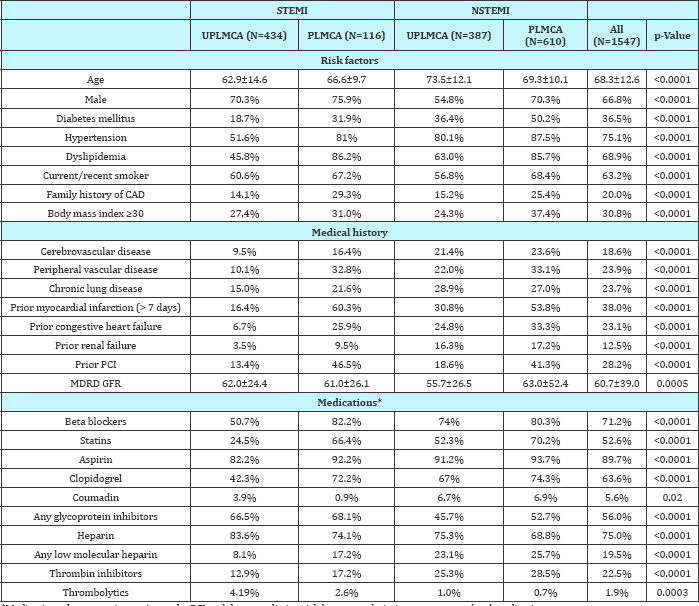

Baseline characteristics

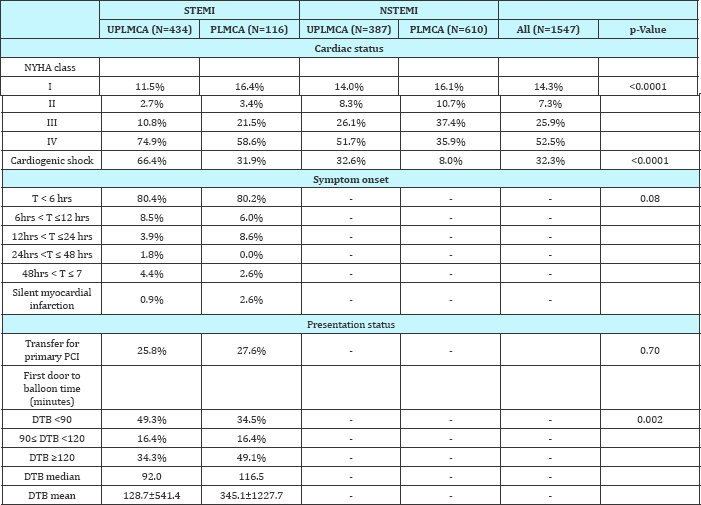

Patients who presented with a STEMI due to an UPLMCA were younger and had lower prevalence of cardiac risk factors and comorbidities compared to those who presented with a NSTEMI or PLMCA STEMI (Table 1). Patients with UPLMCA STEMI had higher prevalence of NYHA Class 4 CHF and cardiogenic shock on presentation compared to the NSTEMI patients and to the STEMI patients with PLMCA (Table 2). Around 25% of STEMI patients were transferred in for primary PCI. Salvage PCI and emergent PCI were performed in 16% and 81% of patients with UPLMCA STEMI respectively.

Table 1: Clinical characteristics.

*Medications that were given prior to the PCI and does not distinguish between admission or pre procedural medications.

CAD: Coronary Artery Disease; GFR: Glomelular Filtration Rate; MDRD: Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; NSTEMI: Non ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction; PCI: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention; PLMCA: Protected Left Main Coronary Artery; STEMI: ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction; UPLMCA: Unprotected Left Main Coronary Artery

Table 2: Presentation characteristics.

DTB: Door to Balloon; NSTEMI: Non ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction; NYHA: New York heart Association; PCI: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention; PLMCA: Protected Left Main Coronary Artery; STEMI: ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction; T: Time; UPLMCA: Unprotected Left Main Coronary Artery

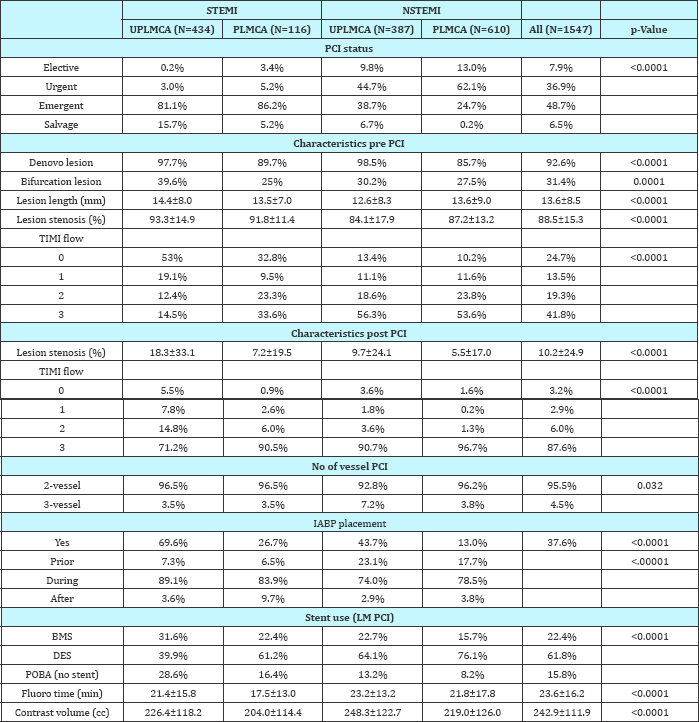

Angiographic and PCI characteristics

Table 3: Left main PCI characteristics.

BMS: Bare Metal Stent; DES: Drug Eluting Stent; IABP: Intraaortic Balloon Pump; NSTEMI: Non ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction; PCI: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention; PLMCA: Protected Left Main Coronary Artery; POBA: Plain Old Balloon Angioplasty; STEMI: ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction; TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; UPLMCA: Unprotected Left Main Coronary Artery

The PCI characteristics are listed in Table 3. Patients with UPLMCA STEMI had significantly (p<0.001) more LM (55% vs 13%), proximal left anterior descending (LAD) (26% vs 9%) and left circumflex (LCX) (24% vs 13%) total occlusions and less right coronary artery (RCA) (9% vs 21%) total occlusions compared to the NSTEMI patients respectively. Patients with UPLMCA STEMI had more bifurcation lesions, longer lesions, more severe diameter stenosis, more residual diameter stenosis, and less pre and post PCI TIMI 3 flow compared to the NSTEMI patients. The majority of STEMI and NSTEMI patients had 2 vessel PCI during the index procedure. An IABP was placed in 70% of patients with UPLMCA STEMI compared to 44% of patients with UPLMCA NSTEMI. The IABP was placed during the PCI in the majority of cases. Plain old balloon angioplasty was performed more commonly in the UPLMCA STEMI group compared to the UPLMCA NSTEMI group (29% vs 13%) and drug eluting stents were implanted more commonly in the UPLMCA NSTEMI group compared to the UPLMCA STEMI group (64% vs 40%).

In-hospital outcomes

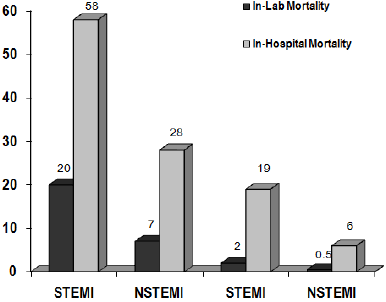

Figure 2: The In-lab and In-hospital Mortality Rates among the 4 Groups of LMCA AMI PCI.

NSTEMI: Non ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction; PLMCA: Protected Left Main Coronary Artery; STEMI: ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction; UPLMCA: Unprotected Left Main Coronary Artery

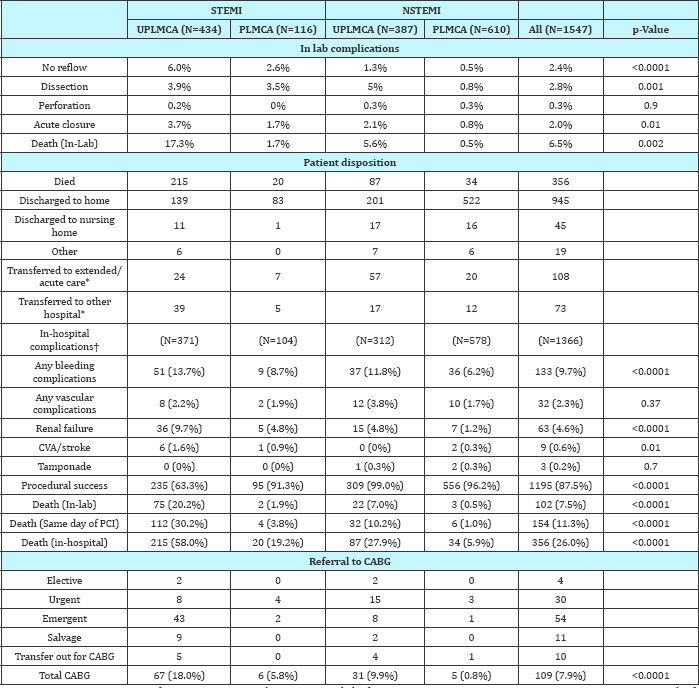

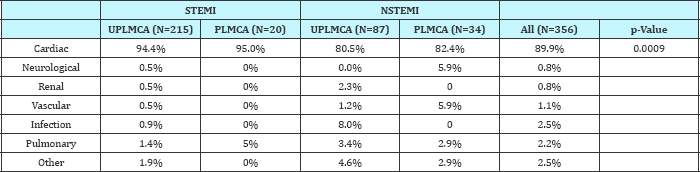

The in-hospital outcomes are listed in Table 4 & 5 and Figure 2. No reflow, dissections, and acute closures were common in the UPLMCA STEMI group (Table 4). The in-lab mortality rate was 17% in the UPLMCA STEMI patients compared to 5.6% in the UPLMCA NSTEMI patients and 1.7% in the PLMCA STEMI patients (Table 4). The in-hospital mortality rate approached 60% in the UPLMCA STEMI group (Table 4). Cardiac death accounted for 94% of the deaths in the UPLMCA STEMI group compared to 80% of the deaths in the UPLMCA NSTEMI group. Of the total cohort of the 434 UPLMCA STEMI patients, 32% of patients were discharged to home. Referral to CABG occurred in 18% of patients with UPLMCA STEMI compared to 10% of the UPLMCA NSTEMI patients who underwent PCI. CABG referral includes patients undergoing PCI who were referred to CABG following the PCI procedure and does not include patients who were referred to CABG after coronary angiography only.

Table 4: Adverse outcomes.

CABG: Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting; NSTEMI: Non ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction; PCI: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention; PLMCA: Protected Left Main Coronary Artery; STEMI: ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction; UPLMCA: Unprotected Left Main Coronary Artery

excluded from in-hospital analysis.

†patients who were transferred out were excluded from in-hospital analysis (the number of patients in each category is less than on admission).

Correlates of in-hospital mortality

The significant univariate factors associated with in-hospital mortality in the UPLMCA STEMI group were age ≥65 years, cerebrovascular disease, GFR <60, cardiogenic shock, NYHA class of 4, salvage PCI, IABP use, total LM occlusion, LAD and LCX occlusions, <3 pre and post PCI TIMI flow, ≥50% residual diameter stenosis, bifurcation lesions, and no-reflow. Beta blocker and statin use, thrombin inhibitor and glycoprotein inhibitor use and stent use were associated with improved in-hospital survival. The significant univariate factors associated with in-hospital mortality in the UPLMCA NSTEMI group were GFR <60, cardiogenic shock, NYHA class of 4, salvage PCI, IABP use, total LM occlusion, bifurcation lesions, <3 pre and post PCI TIMI flow, and ≥50% residual diameter stenosis. Beta blocker and statin use, thrombin inhibitor use and stent use were associated with improved in-hospital survival.

Table 5: Causes of death.

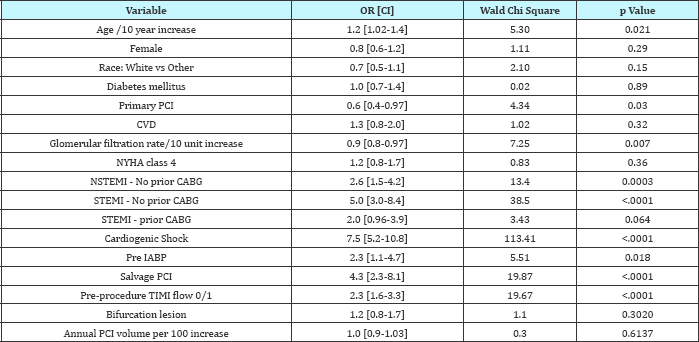

In a multivariate model the significant factors associated with in-hospital mortality were increasing age, primary PCI, decreasing GFR, class 4 NYHA, UPLMCA STEMI and NSTEMI, cardiogenic shock, IABP use, salvage PCI, pre PCI TIMI 0/1 flow, and bifurcation lesions.Cardiogenic shock, STEMI presentation, and salvage PCI were associated with highest odds ratio (OR) of in-hospital mortality of 7.5, 5.0, and 4.3 respectively (Table 6).

Table 6: Multivariate factors associated with in-hospital mortality.

CI: Confidence Interval; CVD: Cerebrovascular Disease; IABP: Intraaortic Balloon Pump; NSTEMI: non ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction; NYHA: New York Heart Association; NSTEMI: non ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction; OR: Odds Ratio; PCI: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention; STEMI: ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction; TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction

Discussion

The current study represents the largest cohort of patients undergoing contemporary PCI of UPLMCA AMI. Although AMI due to a LMCA culprit lesion is a rare event, it carries a very poor inhospital prognosis especially with a STEMI presentation. Patients with UPLMCA STEMI had a high prevalence of cardiogenic shock (66%), NYHA Class 4 CHF (75%) and cardiac arrest (15%) on presentation and consequently had an in-hospital mortality that approached 60%. Also these patients tended to have lower procedural success rates, lower rates of pre and post PCI TIMI 3 flow and higher rates of residual post PCI stenosis all of which are known factors that affect survival post PCI for AMI. A presentation with NSTEMI was associated with better outcomes compared to a STEMI presentation. A history of CABG prior to presentation for LM PCI further conferred better outcomes in the STEMI and NSTEMI groups.

Table 7: Summary of Studies of UPLMCA PCI for AMI.

AMI: Acute Myocardial Infarction; STEMI: ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction.

*54% mortality rate in those who presented with shock.

†32% mortality rate in those who presented with shock (no details on those who presented with STEMI and shock).

The results ofthe current study confirm what has been observed in smaller studies of LMCA AMI. The reported mortality rate of PCI for UPLMCA AMI has ranged from 8% to 82% (Table 7). Cardiogenic shock was present in 24% to 100% of patients (Table 7). In one study, patients with UPLMCA MI who presented with cardiogenic shock had very high in-hospital mortality rates that approached 94% irrespective of management strategy that included medical management, CABG or PCI compared to an in-hospital mortality rate of 6% in those who did not have cardiogenic shock [6]. The AMIS Plus study included 348 patients with STEMI who underwent PCI of UPLMCA [20]. In the AMIS Plus study the frequency of cardiogenic shock was only 12.2% whereas it was 66% in our study and their in-hospital mortality rate was 10.9% [20]. However, the subset of patients who presented with cardiogenic shock had a 54.8% in-hospital mortality rate which is not much different from the mortality rate in our study.

Similar to our study, the small observational studies have reported that patients who had PCI for UPLMCA MI had high rates of TIMI 0 flow pre PCI (46-58%), low rates of post PCI TIMI 3 flow (83%), low angiographic success rates (75-82%), high procedural mortality rates (16-33%) and high rates of IABP use (75-100%) [11,12,15,21,22]. However, stent use in the UPLMCA PCI group in our study was lower (71%) compared to what has been reported (90-100%) [15]. In the ULTIMA registry of UPLMCA PCI in 40 patients who presented with AMI (70% with STEMI), the in-hospital mortality rate was 55% for the entire cohort, 70% for patients who had PTCA only and 35% for the patients who underwent stenting [9]. Stent use in our study was a significant covariate for decreasing in-hospital mortality by 50%.

In previous studies, the univariate predictors of in-hospital mortality were shock, preceding cardiac arrest, and angiographic failure in one study [15] and mechanical ventilation, IABP use, shock, distal LMCA stenosis, RCA occlusion, and incomplete revascularization in another study [11]. Other reported univariate predictors of survival were the presence of intercoronary collaterals, dominant RCA, incompletely occluded LMCA, absence of cardiogenic shock, absence of no-reflow and successful reperfusion [5-9,17]. Shock and incomplete revascularization were the only significant multivariate predictors of in-hospital mortality in 1 study [11] and shock was the most powerful multivariate predictor of in-hospital mortality in 2 other studies [6,20]. The most significant and strongest (OR >2) multivariate correlates of inhospital mortality in our study were salvage PCI, pre PCI TIMI 0/1 flow, UPLMCA PCI and cardiogenic shock that had the highest OR of 7.5. Our study also compared the outcomes of UPLMCA PCI based on type of MI presentation. Patients with UPLMCA PCI for STEMI had higher rates of cardiogenic shock, worse presenting angiographic characteristics and worse outcomes compared to a non STEMI presentation, which has also been reported in smaller observational studies. The Western Denmark Heart Registry studied 344 patients who underwent UPLMCA. PCI (71 STEMI, 157 NSTEMI/unstable angina, 116 stable angina) [23]. Cardiogenic shock was present only in 40% of the STEMI patients who had the lowest pre PCI TIMI 3 flow (62%) [23]. The 30-day mortality rate was 31% in the STEMI group, 6.4% in the NSTEMI/unstable angina group and 3.4% in the stable angina group [23]. The 30-day mortality rate was 55.2% in the STEMI patients who had cardiogenic shock compared to 26.2% in those without cardiogenic shock [23]. In a large multicenter and observational study of 1101 patients who had UPLMCA PCI, 611 patients had unstable angina or NSTEMI [24]. The 2-year cardiac survival was 97% in stable patients, 88% in patients with unstable angina and 82% in patients with NSTEMI [24]. The subset of patients with ACS and UPLMCA revascularization from the GRACE registry included 1799 patients of whom 514 underwent PCI, 612 underwent CABG and 673 underwent no revascularization [25]. STEMI or new LBBB presentation occurred in 35% of patients. Cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest was present in only 3.4% of patients. More patients with STEMI underwent PCI compared to CABG (57% vs 23%) [25]. Patients who underwent PCI also had higher prevalence of cardiac arrest, cardiogenic shock or Killip 4 class [25]. In-hospital death occurred in 11% of patients who had PCI, in 5.4% of patients who had CABG and in 7.6% of patients who were treated medically [25]. The in-hospital death rate was 34% in those patients who presented with cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest (40% in the PCI group and 30% in the CABG group) [25]. Revascularization was associated with an early hazard of hospital death compared to no revascularization that was significant for PCI and not for CABG. However, from discharge to 6 months, both PCI and CABG were significantly associated with improved survival compared to no revascularization [25]. Although our study is not intended to compare outcomes of PCI and CABG, 18% of the 371 patients with UPLMCA PCI underwent CABG. The details regarding CABG referral are not available though around 78% of CABG referrals were emergent or salvage procedures.

Contemporary outcomes of PCI for AMI from the CathPCI Registry have been recently reported [26]. In a contemporary mortality risk prediction model for PCI from the CathPCI Registry, cardiogenic shock and PCI for STEMI (particularly when done emergently or as salvage) were among the factors that had the highest point score or weight [27]. In our study, the unadjusted inhospital mortality rates of PCI of UPLMCA PCI remain substantial and are mainly driven by the high incidence of cardiogenic shock. The outcomes are similar to those of the shock registry where the overall 30-day survival with surgery was 40% in the surgical group when the left main was culprit artery compared to 16% in the PCI group [13]. The use of IABP in our study was not associated with improved survival. A possible explanation is that patients stable enough to undergo CABG for UPLMCA STEMI and shock have better outcomes than those who are resigned to PCI. The outcomes of PCI of UPLMCA STEMI have not changed over the years. It is not known if percutaneous LV assist devices such as Tandem Heart or Impella could provide more support and improve survival in this high risk patient population.

Study Limitations

The CathPCI Registry does not represent all practices in the USA. Moreover, the accuracy of the reported data depends on the accuracy of the individual reporting hospitals without angiographic adjudication. The outcomes of the patients who underwent PCI and subsequently transferred out from the participating hospitals were not available for study. Excluding these patients from the in-hospital analysis reduced the overall sample size. Additionally, it is difficult to assess if there was a bias with the exclusion of these patients. Prior CABG was taken as a surrogate for the degree of LM protection from bypass grafts as there was no routine angiographic review and as it was not possible to define UPLMCA from the available data in the NCDR registry. The frequency of patients who presented with LM instent thrombosis as the culprit for the MI, the strategy for LM PCI (provisional LM stenting, bifurcation stenting technique) and long term outcomes were not available in our database. The number of patients who were referred to CABG after coronary angiography only was not available thus limiting the comparison of the outcomes between PCI and CABG for AMI due to UPLMCA. Furthermore, although we looked at associated outcomes, we could not determine causality from observational data.

Conclusion

PCI for UPLMCA AMI is a rare event that carries a very high in-hospital mortality rate. Patients with a STEMI presentation compared to a non STEMI have worse clinical and angiographic characteristics, higher rates of cardiogenic shock, and higher procedural and in-hospital mortality rates. Patients with CABG and a presumed protected LM have overall a lower risk profile and better in-hospital survival.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the American College of Cardiology Foundation's NCDR (National Cardiovascular Data Registry). The views expressed in this manuscript represent those of the author(s), and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NCDR or its associated professional societies identified at www.ncdr.com

References

- Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Bailey SR, Bittl JA, et al. (2013) 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 82(4): E266-E355.

- Morice MC, Serruys PW, Kappetein AP, Feldman TE, Stahle E, et al. (2010) Outcomes in patients with de novo left main disease treated with either percutaneous coronary intervention using paclitaxel-eluting stents or coronary artery bypass graft treatment in the Synergy Between Percutaneous Coronary Intervention with TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery (SYNTAX) trial. Circulatio 121(24): 2645-2653.

- Naik H, White AJ, Chakravarty T, Forrester J, Fontana G, et al. (2009) A meta-analysis of 3,773 patients treated with percutaneous coronary intervention or surgery for unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2(8): 739-747.

- Park DW, Kim YH, Yun SC, Lee JY, Kim WJ, et al. (2010) Long-term outcomes after stenting versus coronary artery bypass grafting for unprotected left main coronary artery disease: 10-year results of bare- metal stents and 5-year results of drug-eluting stents from the ASAN- MAIN (ASAN Medical Center-Left MAIN Revascularization) Registry. J Am Coll Cardio 56(17): 1366-1375.

- De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Thomas K, van 't Hof AW, de Boer MJ, et al. (2003) Outcome in patients treated with primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction due to left main coronary artery occlusion. Am J Cardiol 91(2): 235-238.

- Quigley RL, Milano CA, Smith LR, White WD, Rankin JS, et al. (1993) Prognosis and management of anterolateral myocardial infarction in patients with severe left main disease and cardiogenic shock. The left main shock syndrome. Circulation 88(5 Pt 2): II65-1170.

- Tang HC, Wong A, Wong P, Chua TS, Koh TH, et al. (2007) Clinical features and outcome of emergency percutaneous intervention of left main coronary artery occlusion in acute myocardial infarction. Singapore Med J 48(12): 1122-1124.

- Yip HK, Wu CJ, Chen MC, Chang HW, Hsieh KY, et al. (2001) Effect of primary angioplasty on total or subtotal left main occlusion: analysis of incidence, clinical features, outcomes, and prognostic determinants. Chest 120(4): 1212-1217.

- Marso SP, Steg G, Plokker T, Holmes D, Park SJ, et al. (1999) Catheter- based reperfusion of unprotected left main stenosis during an acute myocardial infarction (the ULTIMA experience). Unprotected Left Main Trunk Intervention Multi-center Assessment. Am J Cardiol 83(11): 1513-1517.

- Yap J, Singh GD, Kim JS, Soni K, Chua K, et al. (2017) Outcomes of primary percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction due to unprotected left main thrombosis: The Asia-Pacific Left Main ST- Elevation Registry (ASTER). J Interv Cardiol.

- Hurtado J, Pinar Bermudez E, Redondo B, Lacunza Ruiz J, Gimeno Blanes JR, et al. (2009) Emergency percutaneous coronary intervention in unprotected left main coronary arteries. Predictors of mortality and impact of cardiogenic shock. Rev Esp Cardiol 62(10): 1118-1124.

- Lee MS, Sillano D, Latib A, Chieffo A, Zoccai GB, et al. Multicenter international registry of unprotected left main coronary artery percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents in patients with myocardial infarction. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 73(1): 15-21.

- Pyxaras SA, Hunziker L, Chieffo A, Meliga E, Latib A, et al. (2016) Longterm clinical outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting for acute coronary syndrome from the DELTA registry: a multicentre registry evaluating percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting for left main treatment. EuroIntervention 12(5): e623-e631.

- Lee SW, Hong MK, Lee CW, Kim YH, Park JH, et al. (2004) Early and late clinical outcomes after primary stenting of the unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis in the setting of acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 97(1): 73-76.

- Prasad SB, Whitbourn R, Malaiapan Y, Ahmar W, MacIsaac A, et al. (2009) Primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction caused by unprotected left main stem thrombosis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 73(3):301-307.

- Ramos R, Patricio L, Abreu A, Soares C, Mamede A, et al. (2008) Left main percutaneous coronary intervention in ST elevation myocardial infarction. Rev Port Cardiol 27(7-8): 965-973.

- Uretsky BF, Mathew J, Ahmed Z, Hakeem A (2016) A Percutaneous management of patients with acute coronary syndromes from unprotected left main disease: A comprehensive review and presentation of a treatment algorithm. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 87(1): 90-100.

- Tan CH, Hong MK, Lee CW, Kim YH, Lee CH, et al. (2008) Park SW, Park SJ. Percutaneous coronary intervention with stenting of left main coronary artery with drug-eluting stent in the setting of acute ST elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 126(2): 224-248.

- Weintraub WS, McKay CR, Riner RN, Ellis SG, Frommer PL, et al. (1997) The American College of Cardiology National Database: progress and challenges. American College of Cardiology Database Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol 29(2): 459-465.

- Pedrazzini GB, Radovanovic D, Vassalli G, Surder D, Moccetti T, et al. (2011) Primary percutaneous coronary intervention for unprotected left main disease in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction the AMIS (Acute Myocardial Infarction in Switzerland) plus registry experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 4(6): 627-633.

- Lee MS, Dahodwala MQ (2015) Percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction due to unprotected left main coronary artery occlusion: status update 2014. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 85(3): 416-420.

- 22. Yamane M, Inoue S, Yamane A, Kinebuchi O, Yokozuka H (2005) Primary stenting for left-main shock syndrome. EuroIntervention 1(2): 198-203.

- Jensen LO, Kaltoft A, Thayssen P, Tilsted HH, Christiansen EH, et al. Outcome in high risk patients with unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 75(1): 101-108.

- Palmerini T, Sangiorgi D, Marzocchi A, Tamburino C, Sheiban I, et al. (2010) Impact of acute coronary syndromes on two-year clinical outcomes in patients with unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis treated with drug-eluting stents. Am J Cardiol 105(2): 174-178.

- Patel N, De Maria GL, Kassimis G, Rahimi K, Bennett D, et al. (2014) Outcomes after emergency percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with unprotected left main stem occlusion: the BCIS national audit of percutaneouscoronary intervention 6-year experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 7(9): 969-980.

- Roe MT, Messenger JC, Weintraub WS, Cannon CP, Fonarow GC, et al. (2010) Treatments, trends, and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction and percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 56(4): 254263.

- Brennan JM, Curtis JP, Dai D, Fitzgerald S, Khandelwal AK, et al. (2013) Enhanced mortality risk prediction with a focus on high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention: results from 1,208,137 procedures in the NCDR (National Cardiovascular Data Registry). JACC Cardiovasc Interv 6(8): 790-799.

- Wang LF, Xu L, Yang XC, Ge YG, Wang HS, et al. (2006) [Primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction induced by left main artery occlusion or severe stenosis]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi 34(1): 5-7.

- Christiansen EH, Lassen JF, Andersen HR, Krusell LR, Kristensen SD, et al. (2006) Outcome of unprotected left main percutaneous coronary intervention in surgical low-risk, surgical high-risk, and acute myocardial infarction patients. EuroIntervention 1(4): 403-408.

- Pappalardo A, Mamas MA, Imola F, Ramazzotti V, Manzoli A, et al. (2011) Percutaneous coronary intervention of unprotected left main coronary artery disease as culprit lesion in patients with acute myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 4(6): 618-626.

© 2018 Gilbert J Zoghbi, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)