- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Practices in Medical Study

Beyond the Thermometer: Navigating the Heat- Driven Links between Climate Change and Women’s Health in Pakistan

Farhana Tabassum*, Zayaan Delawalla, Shafaq Nami, Aadarsh Arif and Jai Das

Institute for Global Health and Development, Aga Khan University, Pakistan

*Corresponding author:Farhana Tabassum, Institute for Global Health and Development, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan

Submission: August 01, 2024;Published: August 30, 2024

NPMSVolume1 Issue4

Abstract

Pakistan faces a complex intersection of climate change, maternal and child health, and extreme heat, demanding urgent action. The continuous combustion of fossil fuels and exploitation of natural resources drive climate change, posing severe global threats. The resulting impacts, such as extreme heat events, rising sea levels, and intensified weather phenomena, heighten the vulnerability of nations. In this context, Pakistan, ranked as the 5th most climate-vulnerable country, stands out in the South Asian landscape, experiencing climate-related challenges across economic and human development aspects, including variations in precipitation, heatwaves, floods, and glacial melt. Extreme heat has emerged as a growing threat to community well-being, exacerbating health conditions and facilitating disease transmission, with maternal and child health vulnerabilities exacerbated. Furthermore, the intersectionality of climate change, gender, and cultural factors amplifies challenges, with pregnant women, particularly those with lower socioeconomic status, facing heightened vulnerability due to gender inequities, restricted resources, and cultural norms. Addressing these challenges necessitates urgent climate policies and funding, with a specific focus on pregnant women and infants. Prioritizing women in interventions is essential, considering resource disparities and gender imbalances. Swift and comprehensive efforts on a global scale are imperative to mitigate the impact of climate change on vulnerable populations.

Keywords:Climate change; Heatwaves; Fossil fuels

Introduction

Climate change, stemming from the continuous combustion of fossil fuels for power generation, global transport, construction, industrial applications and the exploitation of natural renewable resources through deforestation, overfishing, and mining has emerged as a grave threat to both human well-being and global environmental stability [1]. Its repercussions are far-reaching, encompassing a spectrum of detrimental impacts, notably extreme heat events, escalating sea levels, and a surge in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather phenomena such as hurricanes, droughts, and floods. The cumulative effect of detrimental human activities has already led to a discernible 1.1 °C rise in global temperatures from preindustrial levels, with a projected 1.5 °C increase between 2030 and 2052, which would be devastating for human life [2]. Climate change intersects public health not only through a rise in diseases and fatalities as a result of extreme weather events but also by eroding social determinants of health through economic instability and food insecurity [3,4]. The urgency of this impending crisis underscores the imperative for swift and comprehensive climate mitigation efforts on a global scale.

It is crucial to contextualize these challenges within the broader framework of Asia, a region disproportionately vulnerable to the ravages of a changing climate. In the South Asian landscape Pakistan, ranked the 5th most climate vulnerable country according to Global Climate Risk Index, stands out as particularly susceptible, grappling with a myriad of climate-related issue [5]. The climate crisis characterized by variations in precipitation, heatwaves, floods, and glacial melt, permeates every facet of Pakistan’s economic and human development [6]. As we navigate the intricate intersections of climate change and public health, it is imperative to develop a nuanced understanding of the specific challenges that confront Pakistan, recognizing its vulnerability within the broader Asian and global context [7]. One such challenge are the soaring temperatures and extreme heat events in Pakistan, particularly during the months of May to July, creating a high-risk environment for heat-related emergencies. These heat related health risks, such as dehydration, heat cramps, heat exhaustion, heatstroke, and even fatalities, disproportionately affect the most vulnerable populations including women and children [8].

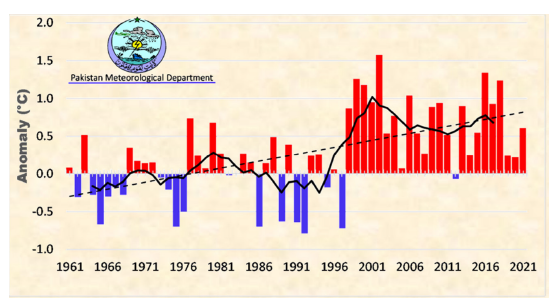

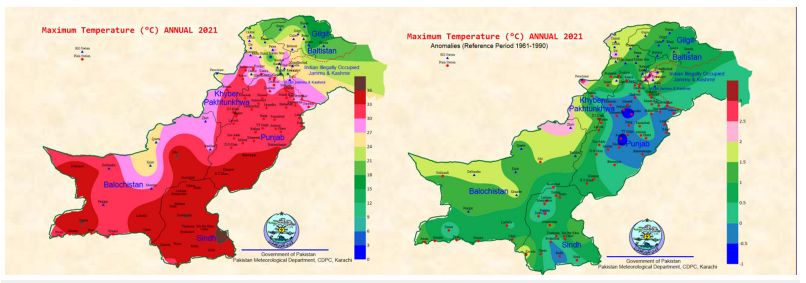

Over the period 1980-2007, Pakistan experienced a notable increase in the number of heat wave days annually, at a pace of 11 days per decade. The occurrence of heat wave incidents decreased in frequency between 1961 and the 1990’s. Nonetheless, a rise in the frequency of these occurrences is noted between 1990 and 2011. Long-term high temperatures are predicted to cause heat waves to become more often and strong everywhere in the world, including Pakistan [9]. The 2015 heatwave in Karachi, claiming over 1200 lives in four days, exemplifies the severity of heat-related emergencies in the region (Figure 1) [9,10]. Despite 2023 being the warmest year on record globally and temperatures showing a consistent annual upward trend, political manifestos for the 2024 Pakistan elections overlook heatwaves and chronic heat impacts in their strategies to combat climate change [11]. Against this backdrop, the urgency of addressing the impact of climate change on vulnerable populations in particular on maternal and child health in Pakistan becomes even more pronounced (Figure 2).

Figure 1:Pakistan annual mean temperature anomalies (with 1961-1990 the base period) for the period 1961-2021. The blackline indicates the 7-year moving average. The value for 7-year average is positioned over the middle year of each 7-year block. The black dotted line shows the trend over the period [10].

Figure 2:Spatial distribution of annual maximum temperature in Pakistan for 2021[10].

Heatwaves Unleashed: A Growing Threat to Community Well-being

Pakistan’s vulnerability to weather-related events intensifies climate risks, impacting maternal and newborn health, high fertility rates, and healthcare gaps. Despite some progress, comprehensive interventions and sector coordination are essential. Heat stress during pregnancy leads to adverse outcomes, including preterm births, neonatal mortality, and cardiovascular issues [12,14]. High temperatures are linked to emergency hospital admissions, gestational diabetes, and increased cardiovascular risks during labor [15]. Prolonged heat exposure compromises fetal health, reducing uterine blood flow and oxygen transfer [16]. Children bear long-term consequences, with estimates attributing up to 88% of climate-related disease burdens. Infants, especially in lowincome settings, face excess mortality during extreme heat [17]. Addressing this requires healthcare programs with sustainable systems, encompassing home-based care, referral facilities, and maternal health initiatives.

Intersectionality and Climate Justice: Examining the Nexus of Women, Culture, and Environment

Pregnant women in Pakistan are especially vulnerable to natural disasters as a result of entrenched gender inequities in society [15,16] . Women, especially those with lower socioeconomic status, have less access to valued resources, restricted decision-making authority, insufficient knowledge and fewer coping mechanisms [18]. They are further hampered by frequent load shedding and power outages, poor infrastructure facilities, and strained access to healthcare facilities, even in life-threatening situations. Furthermore, malnutrition and food security are significantly exacerbated by severe droughts and frequent heavy precipitation events [19]. This is only exacerbated by the gendered differences in access to cool spaces due to modesty reasons: While men enjoy the privilege of venturing out of the house to hotels and community centers in the evenings, women remain within the confines of the household, which are often built without adhering to building codes leading to no considerations for protection against extreme heat. Furthermore, the traditional practice of chilla, a practice where women do not bathe for 40 days after childbirth, removes another avenue for cooling and acutely impacts their overall health and well-being [8].

Additionally, the role of women in agriculture is sorely undervalued. Women in rural Sindh labor an average of 12-14 hours every day in the hot outdoors [20]. Working in the fields does not exempt them from the traditional duties of childcare and their young children are also exposed to the extreme heat with no protection measures in place. Pregnant women in rural areas are expected to carry out their responsibilities till term which can adversely affect the physical and mental health of both pregnant women and children, leading to an increased risk of preterm birth, problems with breastfeeding, increased risk of infant mortality, and long-term developmental issues for the children [8,21].

Conclusion

Pakistan faces challenges at the intersection of climate change, maternal and child health, and extreme heat. Urgent climate policies and funding, especially for pregnant women and infants, are needed for effective adaptation. Prioritizing women in interventions is essential due to resource disparities and gender imbalances.

References

- (2024) International Energy Agency (IEA).

- Seneviratne S, Zhang X, Adnan M, Badi W, Dereczynski C, et al. (2021) Weather and climate extreme events in a changing climate. In: Delmotte VM, Zhai P, Pirani A, Connors SL, Péan C, et al. (eds.), Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, USA, pp. 1513-1766.

- Laurent JGC, Williams A, Oulhote Y, Zanobetti A, Allen JG, et al. (2018) Reduced cognitive function during a heat wave among residents of non-air-conditioned buildings: An observational study of young adults in the summer of 2016. PLoS medicine 15(7): e1002605.

- Shah KG, Rashid M, Moazzam M, Nizami SF. An analysis of the national health vision Pakistan (2016-2025).

- (2023) United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) Country report Islamabad, Pakistan.

- (2022) Pakistan Floods 2022: Post-Disaster Needs Assessment (PDNA).

- Cabrera AMV, Scovronick N, Sera F, Royé D, Schneider R, et al. (2021) The burden of heat-related mortality attributable to recent human-induced climate change. Nature climate change 11(6): 492-500.

- (2023) A burning emergency extreme heat and the right to health in Pakistan.

- Chaudhry QUZ (2017) Climate change profile of Pakistan: Asian development bank.

- (2022) Pakistan meteorological department CDPC, Karachi director, climate data processing centre, Government of Pakistan, Pakistan.

- (2024) Climate crisis, main slider, Pakistan general elections, Pakistan general elections 2024 turning up the 'heat' on manifestos of political parties.

- Zhao Q, Guo Y, Ye T, Gasparrini A, Tong S, et al. (2021) Global, regional, and national burden of mortality associated with non-optimal ambient temperatures from 2000 to 2019: A three-stage modelling study. The Lancet Planetary Health 5(7): e415-e25.

- (2024) Relief, rehabilitation and settlement department government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa: Heat wave action plan.

- Abbas F, Kumar R, Mahmood T, Somrongthong R (2021) Impact of children born with low birth weight on stunting and wasting in Sindh province of Pakistan: A propensity scores matching approach. Scientific Reports 11(1): 19932.

- Samuels L, Nakstad B, Roos N, Bonell A, Chersich M, et al. (2022) Physiological mechanisms of the impact of heat during pregnancy and the clinical implications: Review of the evidence from an expert group meeting. International Journal of Biometeorology 66(8): 1505-1513.

- Bonell A, Sonko B, Badjie J, Samateh T, Saidy T, et al. (2022) Environmental heat stress on maternal physiology and fetal blood flow in pregnant subsistence farmers in the Gambia, west Africa: An observational cohort study. The Lancet Planetary Health 6(12): e968-e76.

- Bhutta ZA, Aimone A, Akhtar S (2019) Climate change and global child health: What can paediatricians do? Arch Dis Child 104(5): 417-418.

- Zachariah M, Arulalan T, AchutaRao K, Saeed F, Jha R, et al. (2022) Climate change made devastating early heat in India and Pakistan 30 times more likely. World Weather Attribution.

- Blom S, Bobea AO, Hoddinott J (2022) Heat exposure and child nutrition: Evidence from West Africa. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 115: 102698.

- (2022) Government of Sindh Environment, Climate Change and Coastal Development Department Directorate of Climate Change, Pakistan.

- Shankar K, Hwang K, Westcott JL, Saleem S, Ali SA, et al. (2023) Associations between ambient temperature and pregnancy outcomes from three south Asian sites of the global network maternal newborn health registry: A retrospective cohort study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 130 (Suppl 3) : 124-33.

© 2024. Farhana Tabassum. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)