- Submissions

Full Text

Modern Research in Dentistry

Vascular Malformation: Unusual and Rare Presentation

Pramod John*1, Anwesha Biswas2 and Jayesnee VM3

1Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Director of Research, Professor, Guru Nanak Institute of Dental Sciences, Formerly, Professor and Head, Amrita School of Dentistry, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham University, India

2Assistant Professor in Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Guru Nanak, institute of Dental Sciences, India

3Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, PSM Dental College and Hospital, India

*Corresponding author: Pramod John, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Director of Research, Professor, Guru Nanak Institute of Dental Sciences, Formerly, Professor and Head, Amrita School of Dentistry, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham University, Kerala, India

Submission: July 21, 2025;Published: August 01, 2025

ISSN:2637-7764Volume8 Issue4

Abstract

Background: Lymphangioma Circumscriptum (LC) is a well circumscribed lymphatic malformation

characterized by small clusters of vesicles like frogspawn. Intra oral LC is commonly seen on the dorsum

of the tongue. The clinical significance of the lesion is the tendency for bleeding.

Case presentation: Two patients reported with similar looking lesions on the tongue. One was 51-yearold

female patient and the other 52-year-old male patient. Both complained about bleeding tendency on

cleaning the tongue.

Conclusion: Oral lymphangiomas are rare with no risk of malignant transformation. There is no racial

predominance and show equal sex predilection. Present at any age, mainly at birth or early in life. Infection

is the most common complication. If traumatized, it can cause minor bleeding. However, sometimes it can

cause a diagnostic challenge especially to the inexperienced clinicians.

Keywords:Lymphangioma circumscriptum; Vascular malformation; Bleeding; Hemangioma; Hematoma

Introduction

Lymphangioma Circumscriptum (LC) is a benign lymphatic malformation that is superficial and well-defined, classified as a hamartoma. Hamartoma is defined as tumorlike malformation characterized by histologic tissue in improper proportion and distribution with prominent excess of one type over the other. A hamartoma is a tumorlike malformation characterized by the disorganized arrangement of normal histological tissues, often with one tissue type being more prevalent than others. LC was initially described by Redenbacher in 1828 [1,2] further elaborated by Fox and Fox in 1878, and the term ‘lymphangioma circumscriptum’ was introduced by Malcolm Morris in 1889 [3]. The precise cause of LC is not fully understood, although lymphatic obstruction has been proposed as a potential contributing factor. Cases of LC linked to conditions such as filariasis, previous surgeries, or radiotherapy have been reported in the literature. Typically, LC manifests either at birth or during childhood, with frequent locations being the axillary folds, shoulders, neck, proximal limbs, perineum, tongue, and buccal mucosa. The pathogenesis of LC was thoroughly investigated by Whistler in 1976 [4], who suggested that the condition arises from the formation of lymphatic cisterns in the deep subcutaneous layer, which remain disconnected from the normal lymphatic system but connect to the superficial vesicles via dilated vertical lymphatic channels. It was proposed that these cisterns may develop from primitive lymph sacs that do not form connections during embryonic development, although the cause of this disconnection is unknown. The rhythmic contractions of the muscle coat and increased intramural pressure within these cisterns are thought to cause the dilated channels to protrude towards the skin or mucosa, resulting in the characteristic vesicles of LC. Imaging and lymphangiographic studies have corroborated these observations, revealing multilobulated cisterns extending deep into the dermis, often extending beyond the clinically visible lesions, while showing no communication with adjacent normal lymphatics.

Lymphangiomas, which include Lymphatic Malformations (LC), are uncommon and typically do not present a significant risk for malignant transformation. They can manifest in individuals of any age, although they are most often detected at birth or in early childhood, with no racial bias and an equal incidence in both genders. Nonetheless, instances of late-onset LC have also been documented. Lymphangiomas can be categorized into four types: [5] lymphangioma simplex (also known as capillary lymphangioma or LC), cavernous lymphangioma, cystic lymphangioma (cystic hygroma), and benign lymphangioendothelioma (acquired progressive lymphangioma). Among this classification, LC is the most commonly prevalent type, usually appearing as clusters of small vesicles that resemble frog spawn. Frog spawns are jelly-like eggs laid by frogs in shallow waters. These vesicles may contain clear, pink, or dark red fluid and are generally asymptomatic, although there can be spontaneous occurrences of minor bleeding or the leakage of clear fluid from ruptured vesicles often associated with traumatic events. LC typically affects extra oral areas such as the axillary folds, shoulders, neck, proximal limbs, perineum, tongue, and buccal mucosa, but it has also been observed in deeper locations such as the intestines, pancreas, and mesentery. Oral lymphangiomas are rare, most commonly affecting the anterior two-thirds of the tongue on the dorsal surface and usually range in size from 1 to 5mm.

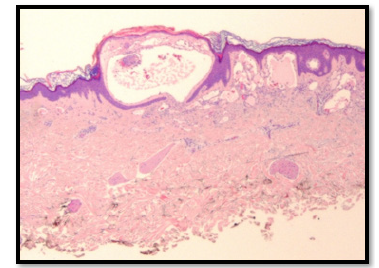

A classification system for lymphangiomas located in the head and neck region, based on their anatomical distribution, was introduced by De Serres LM et al. [6], categorizing them into stages from Class I (infrahyoid unilateral lesions) to Class VI (infrahyoid bilateral lesions), which assists in treatment planning and prognosis [6,7]. The other stages being Class II (suprahyoid bilateral lesions), Class III (suprahyoid or infrahyoid), Class IV (suprahyoid bilateral lesions), Class V (suprahyoid or infrahyoid bilateral). Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) plays a crucial role in evaluating the extent and anatomical involvement of Lymphatic Malformations (LC). Immunohistochemical analyses are instrumental in differentiating lymphangiomas from hemangiomas, while dermoscopy can aid in the diagnosis of cutaneous LC. The diagnosis is primarily based on clinical history and physical examination, supplemented by histopathological assessment. Microscopically, LC is identified by the presence of dilated lymphatic vessels within the superficial dermis, which often leads to the expansion of the papillary dermis, along with additional features such as acanthosis and hyperkeratosis. The dilated vessels, which are lined by flat endothelial cells and encircled by smooth muscle, may contain lymphatic fluid, red blood cells and inflammatory cells including lymphocytes, macrophages and neutrophils [8].

Surgical excision is considered the preferred treatment, particularly for larger lesions [9]. Other treatment options include radiofrequency ablation and palliative coagulation utilizing radiofrequency currents, CO₂ laser vaporization and flash lamp pulsed dye laser therapy [10,11]. Additional techniques such as suction-assisted lipectomy and intralesional sclerotherapy with agents like 1% sodium tetradecyl sulphate or hypertonic saline have been used with varying degrees of success. Despite these interventions, recurrence may occur in about 15% of cases, especially due to the persistence of deeper lymphatic channels that are difficult to completely excise during surgical procedures. Vascular malformations, despite being distinct in their pathological origins, often exhibit similar clinical appearances, making their differentiation challenging in practice. Accurately identifying and categorizing these lesions requires careful clinical evaluation and at times, additional imaging and histopathological assessment to avoid misdiagnosis. This overlap in presentation frequently poses a diagnostic dilemma for clinicians, emphasizing the need for a systematic approach while evaluating such lesions.

Case Presentations

Case-1

Figure 1:Image showing facial profile (Case 1).

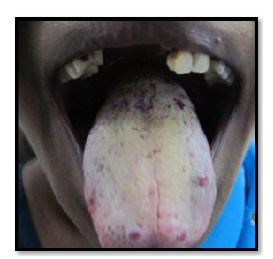

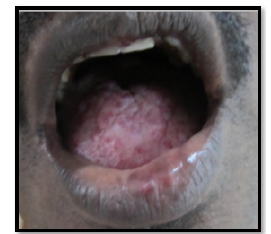

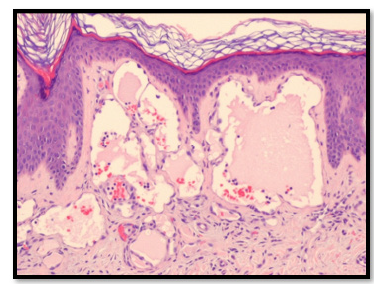

The 51 years old female patient came to the department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Amrita School of Dentistry, Cochin with a complaint of reddish patches on the tongue without any symptoms since many years. Bleeding was present on vigorous cleaning of the tongue. No known drug allergies or any medical problems. No history of any disease running in the family. Medical history revealed no systemic illnesses. On examination, the right submandibular lymph node was palpable, firm and non-tender. Intra-orally, coated and fissured tongue with tiny reddish, depopulated, elevated, circular spots, 6-8 in number and 2-4mm in diameter, located towards the anterior part of the tongue and in front of circumvallate papillae (Figure 1 & 2). These are non-tender and compressible with no bleeding tendency on palpation. Diascopy demonstrated blanching and was thus confirmed as vascular lesion. Differential diagnosis of lymphangioma circumscriptum, Hemorrhagic blebs, hematoma, hemangioma were considered. Based on the unique presentation of the lesion and long duration of existence as an asymptomatic lesion, lymphangioma circumscriptum was considered as the most probable diagnosis (Figure 3). No medicines were given for the lesion as it was asymptomatic. Patients were advised not to vigorously clean their tongue to prevent bleeding.

Figure 2:Clinical photograph showing a coated tongue with yellowish discoloration and patchy depopulation, along with prominent fissuring and erythematous areas.

Figure 3:Histopathologic examination showing Lymphangioma Circumsciptum (Case 1).

Case-2

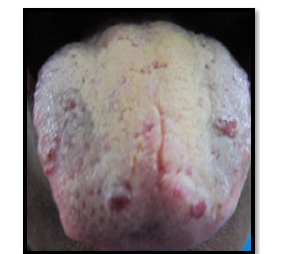

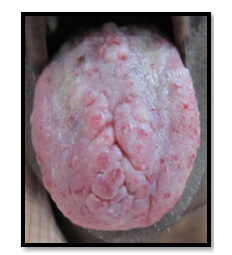

The 52-year-old male patient reported with burning sensation of the tongue while eating hot and spicy food for 2 weeks on the same day to the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Amrita School of Dentistry, Cochin. He noticed a single red spot on the tongue 4 years back. There was bleeding from the tongue on having hard food and burning sensation for 2 weeks. 4 years back he underwent an intracranial surgery for some ailment, the nature of which was not known to the patient. Epistaxis was reported since childhood and family history of the same. He has been a smoker for 20 years (15 cigarettes per day). On examination, pallor present. Labial mucosa showed 4 circular red macular spots of 2mm diameter. More than 10 erythematous macular spots 2-4mm in diameter with a tendency to bleed on applying digital pressure and clear fluid filled 1mm vesicles are seen on the dorsum of the tongue. Fissured tongue and macroglossia seen (Figure 2,4 & 5). Palate showed irregular reddish areas and smoker’s palate Figure 4 & Figure 5. Diascopy showed blanching suggestive of vascular lesion. Smear stained with H&E revealed candidal hyphae. The hemogram revealed Hb: 5.78g/dl, and HCT: 22 % (Figure 6).

Figure 4:Image showing Clinical Profile (Case 2).

Figure 5:Clinical photograph showing an enlarged, lobulated, and fissured tongue with nodular surface changes, suggestive of scrotal tongue (fissured tongue) in an adult patient.

Figure 6:Histopathologic examination showing Lymphangioma Circumsciptum (Case 2).

Differential diagnosis of lymphangioma circumscriptum, hemorrhagic telangiectasia, oral candidiasis, iron deficiency anemia, Moeller’s or Hunter’s glossitis, granular cell myoblastoma were considered. Unique clinical presentation was in favor of lymphangioma circumscriptum and macroglossia, smoker’s palate and superadded candidiasis. No treatment was advised for the lesion on the tongue; Patient was advised to stop smoking. Topical clotrimazole twice daily for 10 days was advised for superadded candidiasis. Hematinic agents were prescribed. On the followup visit, there was no burning sensation and palatal lesion also subsided. Erythematous areas disappeared, probably attributable to the superadded candidal infection. The reddish macular lesions remained as they were noted on the first visit and there was no bleeding on applying digital pressure (Figure 7).

Figure 7:Intraoral photograph showing erythematous areas on the hard palate suggestive of smoker’s palate.

Discussion

Lymphangioma Circumscriptum (LC) is an uncommon, benign lymphatic malformation distinguished by groups of translucent vesicles on the skin, which represent dilated lymphatic channels located in the superficial dermis. It generally appears at birth or during early childhood, with more than 90% of instances occurring within the first two years of life; However, cases that present later, as seen in our second patient, are rare and often associated with factors such as trauma, infections, or localized lymphatic obstruction that may reveal a subclinical congenital abnormality [12,13]. In both of our cases, diascopy demonstrated blanching, thereby confirming the vascular nature of the lesions. This straightforward clinical tool assists in distinguishing LC from non-blanching lesions such as angiokeratomas and hemorrhagic vesicles, thereby supporting the diagnosis when utilized in conjunction with clinical assessment [3]. The vessels contained either clear or blood-tinged fluid and were asymptomatic apart from occasional oozing, which is consistent with the classic presentation of LC [14]. In contrast to inflammatory or infectious vesicular dermatoses, LC typically follows a chronic, non-inflammatory course, which aids in clinical differentiation.

An atypical aspect in the second case was the occurrence of Iron Deficiency Anemia (IDA), which is not typically linked with LC but may arise from chronic, low-grade blood loss due to vesicle rupture or ongoing oozing over time [15]. Although instances of IDA secondary to LC are uncommon, a comparable case was reported by Bittencourt et al. underscoring the necessity for clinicians to monitor hemoglobin levels in patients with bleeding-prone LC [16]. An unusual aspect in the second instance was the occurrence of Iron Deficiency Anemia (IDA), which is not typically linked with Lymphatic Malformation (LC) but may arise from chronic, lowgrade blood loss due to vesicle rupture or ongoing oozing overtime [17]. Although instances of IDA secondary to LC are infrequent, a comparable case was reported by Bittencourt et al. underscoring the necessity for clinicians to monitor hemoglobin levels in patients with bleeding-prone LC [18]. From a pathophysiological perspective, LC is regarded as a microcystic lymphatic malformation resulting from the sequestration of lymphatic tissue during embryonic development, leading to clusters of dilated lymphatic channels that connect with the superficial dermis [19]. Histologically, it is defined by thin walled, dilated lymphatic spaces lined by a single layer of endothelial cells, which may sometimes extend into the epidermis [8]. Although histopathological confirmation was not achieved in our cases due to the typical clinical features, it remains the diagnostic gold standard when the presentation is atypical.

The treatment of LC presents challenges due to the deep extension of lymphatic channels, which complicate complete surgical excision and contribute to a high recurrence rate [20]. A variety of treatment options, including surgical excision, CO₂ laser ablation, radiofrequency ablation, and sclerotherapy, have been utilized with differing degrees of success, aiming to reduce lesion size, manage bleeding and enhance cosmetic results [21,22]. In our cases, conservative management with regular monitoring was selected due to the localized nature of the lesions and patient preference, with counseling provided regarding the potential for recurrence and the chronic nature of the condition. In comparison, Patel et al. [2] documented a lower limb manifestation of LC characterized by distinct vesicular lesions, akin to our initial case. They emphasized that although the lower limb is an infrequent location, it should be included in the differential diagnosis of chronic vesicular eruptions [23]. Furthermore, Amaral et al. [13] & Agarwal et al. [14] brought attention to late-onset LC in adults, which aligns with our second case, illustrating that while uncommon, LC can manifest in adulthood, frequently linked to bleeding episodes that may lead to IDA [12,13]. These instances highlight the necessity of considering LC when assessing vesicular lesions with vascular features, even in adult patients, to avoid misdiagnosis and unnecessary treatments [24]. Timely identification, suitable counseling and tailored treatment strategies are crucial for effectively managing symptoms, reducing complications such as bleeding and anemia and addressing the aesthetic concerns of patients.

Conclusion

Vascular Lesions are relatively uncommon. However, it must be kept in that vascular malformations can have unusual presentation, lymphangioma circumscriptum is one among such manifestation is one among them. Clinical presentation of lymphangioma circumscriptum helps in confirming.

References

- Reynaldo JSP, De Souza, Luiz G Tone (2001) Treatment of lymphangioma with alpha-2a-interferon. J Pediatr (Rio J) 77(2): 139-142.

- Patel JN, Sciubba J (2003) Oral lesions in young children. Pediatric Clinics of North America 50(2): 469-486.

- Mohanty S, Gandhi V, Sing A (1998) Lymphangioma circumscriptum of scrotum of late onset. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 64(6): 289-290.

- Whimster IW (1976) The pathology of lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol 94(5): 473-486.

- Meher R, Garg A, Raj A, Singh I (2005) Lymphangioma of tongue. The Internet Journal of Otorhinolaryngology 3(2):

- De Serres LM, Sie KC, Richardson MA (1995) Lymphatic malformations of the head and neck: A proposal for staging. Archives of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery 121(5): 577-582.

- Ligia Stănescu (2006) Lymphangioma of the oral cavity-case report. Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology 47(4): 373-377.

- Marissa H, Stephanie M (2008) Lymphangioma circumscriptum. Dermatology Online Journal 14(5): 27

- Browse NL (1986) Surgical management of lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Surg 73(7): 585-588.

- Lapidoth M (2006) Treatment of lymphangioma circumscriptum with combined radiofrequency current and 900nm diode laser. Derm Surg 32(6): 790-794.

- Eliezri YD, Sklar JA (1988) Lymphangioma circumscriptum: Review and evaluation of carbon dioxide laser vaporization. J Derm Surg Oncol 14(4): 357-364.

- Bikowski JB, Dumont AMG (2005) Lymphangioma circumscriptum: Treatment with hypertonic saline sclerotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 53(3): 442-444.

- Amaral MB, Marchiori E, Costa F (2010) Adult-onset lymphangioma circumscriptum: A rare presentation. Radiol Bras 43(1): 59-61.

- Agarwal S, Sharma S, Singh S (2002) Lymphangioma circumscriptum: An unusual presentation. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 68(6): 336-337.

- Greene AK, Perlyn CA, Alomari AI (2011) Management of lymphatic malformations. Clinics in Plastic Surgery 38(1): 75-82.

- Mulliken JB, Glowacki J (1982) Hemangiomas and vascular malformations in infants and children: A classification based on endothelial characteristics. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 69(3): 412-220.

- Giguère CM, Bauman NM, Sato Y, Burke DK, Greinwald JH, et al. (2002) Treatment of lymphangiomas with OK-432 (Picibanil) sclerotherapy: A prospective multi-institutional trial. Archives of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery 128(10): 1137-1144.

- Horbach SE, Lokhorst MM, Saeed P, Rothová A, Van der Horst CM (2016) Sclerotherapy for low-flow vascular malformations of the head and neck: A systematic review of sclerosing agents. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery 69(3): 295-304.

- Redondo P (2007) Vascular malformations (I) Concept, classification, pathogenesis and clinical features. Actas Dermosifiliogr 98(3): 141-158.

- Zaballos P, Del Pozo LJ, Argenziano G, Karaarslan IK, Landi C, et al. (2018) Dermoscopy of lymphangioma circumscriptum: A morphological study of 45 cases. Australas J Dermatol 59(3): e189-e193.

- Leboulanger N, Bisdorff A, Boccara O, Dompmartin A, Guibaud L, et al. (2023) French national diagnosis and care protocol (PNDS, protocole national de diagnostic et de soins): Cystic lymphatic malformations. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 18(1): 10.

- Perkins JA, Manning SC, Tempero RM, Cunningham MJ, Edmonds JL, et al. (2010) Lymphatic malformations: Review of current treatment. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 142(6): 795-803.

- Smith RJ, Burke DK, Sato Y, Poust RI, Kimura K, et al. (1996) OK-432 therapy for lymphangiomas. Archives of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery 122(11): 1195-1199.

- Patel GA, Schwartz RA (2009) Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum: Frog spawn on the skin. International Journal of Dermatology 48(12): 1290-1295.

© 2025 Pramod John. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)