- Submissions

Full Text

Modern Research in Dentistry

The Dental Frontline: Identifying Gastrointestinal Pathologies Through Oral Symptoms

Muhammad Anas1*, Muhammad Farrukh2, Sajid Ali3, Muhammad Usman Sultan1, Ihsan Ullah3 and Mohammed Aizaz Khan1

1BDS Bachelor of Dental Surgery, Bacha Khan College of Dentistry Mardan, Pakistan

2BDS Bachelor of Dental Surgery, Margalla Institute of Health Sciences Rawalpindi, Pakistan

3PGR Department of Prosthodontics, Bacha Khan College of Dentistry Mardan, Pakistan

*Corresponding author: Muhammad Anas, BDS Bachelor of Dental Surgery, Bacha Khan College of Dentistry Mardan, Pakistan

Submission: April 22, 2025;Published: May 27, 2025

ISSN:2637-7764Volume8 Issue2

Abstract

Objective: In this review, various gastrointestinal diseases that can have oral manifestations are

emphasized and discussed, given dental practice.

Data source: To find gastrointestinal diseases that manifest in the oral cavities, a thorough search was

carried out on PubMed, Cochrane, and Google Scholar.

Study selection: This narrative review synthesizes findings from key studies on oral manifestations of

Gastrointestinal (GI) diseases, selected based on clinical relevance, impact and expert consensus. Below.

A total of 57 studies were reviewed, encompassing clinical reports, observational studies and systematic

reviews published between 2000 and 2024.

Conclusion: Dentists must take care when treating individuals with gastrointestinal ailments with

periodontal therapy or dental implants because they risk increased bleeding, infection, or malnutrition.

Although the frequency and specificity of oral manifestations vary across GIDs, they can precede the

underlying disease, facilitating timely diagnosis and interdisciplinary care. Also, the pharmacological

management of these individuals might need personalization.

Keywords:Oral manifestations; Gastrointestinal diseases; Systemic diseases and oral health; Dental implications of GI disorders; Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and oral health; Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) and oral symptoms

Clinical Significance

Oral manifestations of gastrointestinal diseases often serve as early diagnostic indicators, enabling timely intervention and improved patient outcomes. Dentists play a crucial role in identifying these signs, which may precede systemic symptoms, prompting referral to gastroenterologists for comprehensive evaluation. Recognizing these associations enhances interdisciplinary collaboration, optimizing patient care through early detection, tailored treatment, and preventive strategies.

Introduction

The oral cavity and Gastrointestinal (GI) tract share a complex and interconnected relationship, with oral lesions occasionally serving as indicators of underlying GI diseases [1]. These lesions can manifest at various stages of the disease process, including preceding the onset of GI symptoms, persisting during disease progression, or remaining even after disease resolution [1]. The shared embryological origins of the oral cavity and GI tract provide a plausible explanation for the frequent observation of oral manifestations in various GI disorders [2]. Systemic diseases, including Gastrointestinal Disorders (GIDs), are globally prevalent and on the rise and can impact the oral cavity [3]. While GI symptoms are usually paramount, oral manifestations may also occur and sometimes serve as early indicators of an underlying GID [3]. A wide range of GIDs, including those of inflammatory, infectious, genetic and other origins, can lead to hard and soft oral tissue changes [3]. Examples of GIDs that can affect the oral cavity include Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, celiac disease, and gastroesophageal reflux disease [3]. Common oral manifestations of GI diseases include dental erosion, erythema in different areas of the oral cavity, oral ulcers, gingivitis, periodontitis, and glossitis [4]. Many systemic diseases, including Gastrointestinal Disorders (GIDs), can affect the oral cavity [5-20]. Despite the primary presentation of gastrointestinal symptoms, oral manifestations can occur, serving as a potential early warning sign for underlying GIDs [21-35].

Materials and Methods

Study design

This narrative review aims to synthesize and critically evaluate existing literature on the oral manifestations associated with Gastrointestinal Diseases (GIDs). By exploring the complex interplay between oral health and systemic gastrointestinal conditions, this review seeks to provide dental practitioners with a deeper understanding of the topic, ultimately informing the development of effective management strategies and improving patient care.

Search strategy

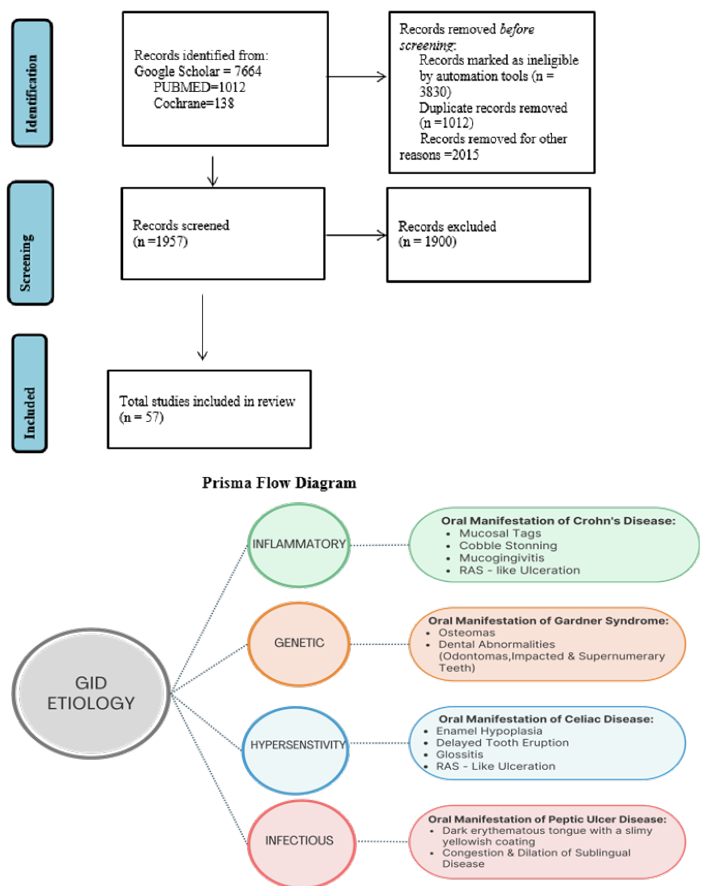

A systematic search of major databases, including PubMed, Cochrane and Google Scholar, was undertaken to identify relevant studies and reviews investigating oral manifestations of gastrointestinal diseases. A tailored search strategy employed a combination of keywords and phrases, such as “oral manifestations,” “gastrointestinal diseases,” “systemic diseases and oral health” and specific terms related to inflammatory bowel disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease and celiac disease. The search was restricted to English-language publications, with no limitations on publication date. A two-step screening process was applied to identified studies, consisting of a title and abstract review, followed by a full-text examination for those meeting the specified criteria. The selected studies were then carefully examined and integrated to provide an in-depth overview of the oral manifestations associated with gastrointestinal diseases, as illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram.

Eligibility criteria Inclusion criteria:

a. Studies discussing oral manifestations of gastrointestinal

diseases in human subjects.

b. Original research articles, clinical studies, and reviews have

been published in peer-reviewed journals.

c. Studies published in English from 2000 to 2024.

Exclusion criteria:

a. Studies focus solely on animal models or in vitro experiments.

b. Articles without specific mention of oral manifestations

related to gastrointestinal diseases.

c. Letters to the editor, case reports, commentaries, and nonpeer-

reviewed publications.

Study selection and data extraction

A dual-review process was employed, where two separate reviewers evaluated the titles and abstracts of identified articles. Relevant studies underwent full-text assessment for eligibility. The extracted data encompassed study methodology and demographic characteristics, the specific gastrointestinal disease under investigation, detailed descriptions of oral manifestations, hypothesized mechanisms connecting GI diseases to oral lesions, and recommendations for dental management and implications.

Data synthesis

Since this is a narrative review, no statistical meta-analysis was performed [16-23]. Findings were synthesized thematically, summarizing key oral manifestations associated with gastrointestinal diseases, their diagnostic significance and clinical management considerations.

Result

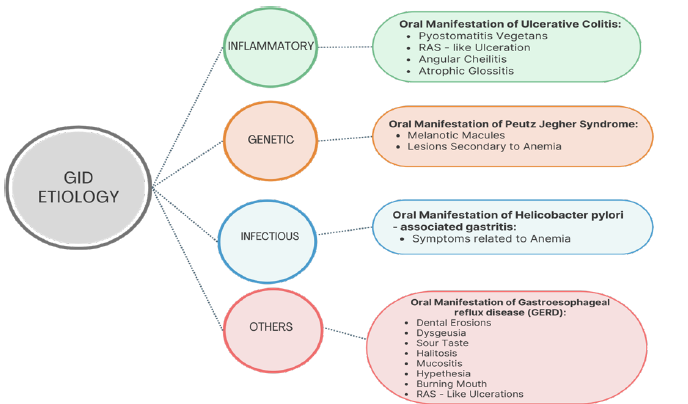

This narrative review synthesizes findings from key studies on oral manifestations of Gastrointestinal (GI) diseases, selected based on clinical relevance, impact and expert consensus. Below, we present major themes and patterns identified in the literature. A total of 57 studies were reviewed, encompassing clinical reports, observational studies and systematic reviews published between 2000 and 2024. A thorough review of the literature revealed that various Gastrointestinal Diseases (GIDs) manifest with distinct oral symptoms, often preceding systemic signs. These oral manifestations vary in presentation, severity and frequency depending on the underlying gastrointestinal condition. The major findings from the reviewed studies are summarized as follows (Figure 1a&b).

Figure 1a:Summary of oral manifestations of gastrointestinal diseases.

Figure 1b:Summary of oral manifestations of gastrointestinal diseases.

RInflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) is a category of chronic inflammatory disorders affecting the gastrointestinal tract, predominantly impacting the intestines, with an uncertain underlying cause [36]. The two main subtypes of IBD are Crohn’s Disease (CD) and Ulcerative Colitis (UC) [2,5]. Although symptoms typically arise from intestinal damage, some individuals may exhibit oral symptoms, which can precede the development of gastrointestinal problems [3,8].

Crohn’s disease

Crohn’s disease is distinguished by persistent inflammation and the development of non-caseating granulomas, which can occur anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract, with a particular affinity for the distal ileum and colon [5,37]. The primary symptoms include diarrhea and abdominal pain, although some patients may also exhibit extraintestinal symptoms affecting various organs, such as the eyes, joints, skin, and oral cavity [7].

Epidemiology: Crohn’s disease predominantly affects males in their third decade of life, though it can occur across various age groups, including young children [36]. Its incidence fluctuates depending on the studied population, with a notably higher prevalence among pediatric patients. Geographical variations exist in disease prevalence, with estimates ranging between 319 and 322 cases per 100,000 individuals [37].

Etiopathogenesis: The precise cause and underlying mechanisms of Crohn’s disease remain unclear [38-47]. It is hypothesized that individuals with a genetic predisposition may develop an abnormal immune response when exposed to various environmental triggers, such as stress, smoking and dietary factors, as well as microbial agents [37]. This immune dysregulation leads to a persistent pro-inflammatory state, ultimately resulting in tissue damage characteristic of the disease [37]. Oral lesions in Crohn’s disease: Oral lesions in Crohn’s disease are more frequently observed in young male patients [5], with a reported prevalence ranging from 20% to 50% [5,7,8]. These lesions are commonly present as ulcers, papules, and swelling, predominantly affecting the lips, gingiva and vestibular sulci [37]. Notably, oral lesions can serve as an early diagnostic indicator of systemic Crohn’s disease [5]. Patients with Crohn’s disease are more likely to develop oral lesions [7], the specific type of lesion does not appear to correlate with disease activity or treatment modality [5,7,8]. Furthermore, multiple lesion types may coexist in the same patient, and histopathological examination categorizes them as either specific or non-specific based on the presence or absence of granulomas [5,7].

Specific oral lesions in Crohn’s disease:

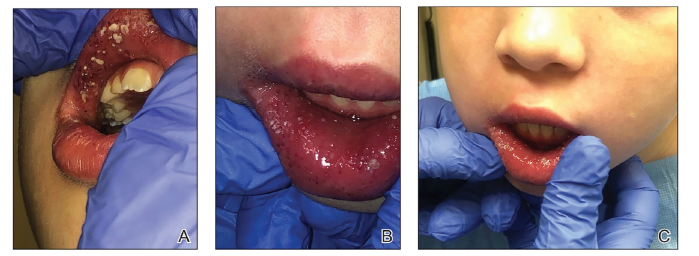

A. Labial swelling and fissuring: Characterized by persistent enlargement of the lips, often accompanied by vertical fissures, cracks, or crusting along the vermilion border [5-7,37] (Figure 2).

Figure 2:Labial mucosa swelling with confluent white pustules and plaques on the upper and lower lips, as observed in this 7-year-old female patient, is a distinctive clinical presentation in Crohn’s diease. Adopted from Pazheri et al. [6].

B. Mucosal tags: Also referred to as epithelial tags or folds, these

appear as whitish or normal-colored reticular projections,

typically found in the vestibular and retromolar regions [5,8].

C. Cobble stoning: The buccal mucosa develops slightly raised,

normal-colored plaques separated by shallow depressions or

fissures, creating a cobblestone-like texture. In some cases,

these lesions may interfere with normal functions such as

mastication [5,36,37].

D. Mucogingivitis: Characterized by hyperplastic and granular

gingival tissue, involving both the free and attached gingiva

[48-51]. In some instances, this condition extends to the

mucogingival junction [7,8,52-63].

E. Linear ulcerations: These elongated ulcers typically develop

in the buccal sulci and are often accompanied by hyperplastic

mucosal borders [5,7,8,61,64] (Figure 3).

Figure 3:Corrugated vestibular mucosa with linear ulceration is a clinical finding consistent with Crohn’s disease. Adopted from Plauth et al. [61].

Non-specific oral manifestations: Recurrent Aphthous

Stomatitis (RAS)-like ulceration is a common oral manifestation

in patients with Crohn’s disease, affecting up to 27% of cases [38].

Clinically, these ulcers present as recurring episodes of multiple,

round or oval-shaped superficial lesions with well-defined borders

and an erythematous halo, closely resembling RAS. However, RASlike

ulcerations must be distinguished from RAS, as the latter occurs

in otherwise healthy individuals [39]. The oral lesions associated

with this condition do not carry the same clinical significance as

intestinal ulcers [7]. Notably, RAS-like lesions are not exclusive

to Crohn’s disease and can be found in various other conditions,

including AIDS, celiac disease, Behcet’s syndrome, and anemia [39].

A. Angular cheilitis: Recurrent fissures and indurated

erythematous plaques may develop at the commissure and

surrounding skin, which are not necessarily linked to Candida

infection. According to Lisciandrano et al. [8], this is the

predominant oral lesion in patients with Inflammatory Bowel

Disease (IBD).

B. Pyo stomatitis vegetans: Even so recognized as an oral

manifestation in Crohn’s Disease (CD) [40], Pyo stomatitis

vegetans are more commonly seen in patients with ulcerative

colitis and will therefore be discussed in the relevant section.

Other non-specific oral findings reported in the literature: Crohn’s disease can present with a variety of oral symptoms, including swollen lymph nodes, dry mouth, tooth decay, bad breath, fungal infections, swallowing difficulties and gum disease. Some patients may also experience changes in taste, tongue inflammation and skin discoloration [5,7]. While many of these symptoms are mild, some individuals may experience more severe effects, such as facial changes and debilitating pain, which can impact on their emotional well-being and quality of life [8].

Ulcerative Colitis (UC)

Ulcerative Colitis (UC) is grouped with Crohn’s Disease (CD) under the umbrella of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IBDs), yet it presents distinct clinical and histopathological characteristics. Unlike CD, UC is characterized by mucosal (inner most lining) involvement in the rectum and colon, with occasional upper GI tract involvement (small intestine) [6,42]. Additionally, UC is characterized by the absence of granulomas, a hallmark of CD [41]. The disease typically follows a pattern of flare-ups and periods of remission and in severe cases, it can involve the entire depth of the intestinal wall, potentially leading to significant bleeding. Common digestive symptoms include chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss and fatigue [41].

Epidemiology: Ulcerative Colitis (UC) is more common in males and occurs at a rate approximately twice as high as Crohn’s Disease (CD) [42]. Unlike CD, UC is typically diagnosed in individuals who are somewhat older, with a mean age of 32 years [41]. The incidence of UC follows a bimodal distribution, with peaks in early adulthood and again between the sixth and seventh decades of life. Europe has the highest incidence, with 24.3 new cases per 100,000 people annually [42].

Etiopathogenesis: As with Crohn’s Disease (CD), the development of Ulcerative Colitis (UC) is believed to be influenced by a combination of microbiological, genetic, and environmental factors, which interact with one another to trigger the onset of the disease [36].

Oral manifestations:

A. Pyo stomatitis Vegetans (PV): Pyo stomatitis vegetans is a distinctive oral manifestation closely linked to Ulcerative Colitis (UC) and pyoderma gangrenosum. Notably, it serves as a specific indicator of disease activity, unlike many other oral lesions [5,6]. Characterized by chronic inflammation, PV involves the formation of multiple pustules filled with white or yellowish content, often on an erythematous and edematous base [6]. These lesions can rupture or coalesce, resulting in a unique ‘snail track’ appearance. Associated symptoms, such as fever, submandibular lymphadenopathy and pain, may occur, although their severity does not always correspond to the extent or size of the ulcers. Lesions have been reported on various oral sites, including the tongue, lips, gingiva, tonsillar pillars, buccal mucosa, and both the soft and hard palate [6]. Despite research efforts, the exact etiology of PV remains unclear, and no specific microbiological agent has been identified as a causative factor [6,63], (Figure 4).

Figure 4:Ulcerative Colitis: Typical clinical features of one patient with Pyo stomatitis Vegetans in a clinic due to

Ulcerative Colitis, Widespread yellow or white pustular lesions as well as its secondary ulcers were observed on the

palate.

(A) the labial gingivae, (B) the anterior floor of mouth, (C) and the lower lip, (D) of the patient PSV, Pyo stomatitis

vegetans due to Ulcerative Colitis. Adopted from Li et al. [13].

B. Other oral lesions: Some patients with ulcerative colitis may present with oral lesions commonly seen in Crohn’s disease, including RAS-like ulcers (affecting up to 13% of cases), glossitis, cheilitis, stomatitis, mucosal ulcers and gingival inflammation [5,8,37]. These oral manifestations are often related to malabsorption of essential nutrients, such as iron, folate, or vitamin B12, resulting from gastrointestinal disease or as an adverse effect of UC [8].

Celiac disease

Celiac disease, also known as coeliac sprue, is an autoimmune

disorder characterized by an adverse immune response to gluten in

genetically susceptible individuals. This reaction leads to damage

to the small intestine’s villi [6]. Diagnosis is based on clinical and

histological findings, which categorize the disease into four main

forms: classical, atypical, silent and latent [43].

Etiopathogenesis: Gluten, a protein in various grains, is

incompletely broken down by digestive enzymes, allowing peptides

to pass through the intestinal lining due to increased permeability.

These peptides are then altered by tissue transglutaminase, making

them more recognizable to immune cells [44]. This triggers an

immune response, where CD4+ lymphocytes react to the peptides,

leading to inflammation and tissue damage through the release of

signaling molecules and enzymes [43].

Epidemiology: Celiac disease affects approximately 1% of the

global population, with a notable increase in prevalence in recent

years, impacting 1 in 85 to 300 individuals [44]. The condition is

more prevalent in European countries and developing regions,

including South America, South Asia and South Africa. While

traditionally diagnosed in childhood, recent studies indicate a

growing number of adult cases. Women are disproportionately

affected, with a female-to-male ratio of 7:1 [44].

Oral manifestations: Celiac disease can be manifested orally

in various ways, which is significant given that 50% of patients

may not exhibit gastrointestinal symptoms at diagnosis [28]. Oral

lesions can serve as an early indicator of atypical celiac disease, the

most frequent form of the condition [44].

A. Dental enamel defects: Individuals with celiac patients are

more likely to experience enamel developmental defects,

particularly enamel hypoplasia [45]. In primary dentition,

second molars are most frequently involved, while in

permanent dentition, central incisors are more commonly

involved. Enamel hypoplasia typically appears symmetrically

on both sides of both dental arches [44,45].

B. Atrophic glossitis and glossodynia: Some individuals with

celiac disease may experience oral symptoms, including

inflammation of the tongue (atrophic glossitis) and a burning

sensation (glossodynia) [44]. Research has shown that the

tongue is often affected, with some patients reporting pain and

changes in appearance, such as redness or shrinkage. These

symptoms are likely related to nutritional deficiencies and

anemia [46].

C. Salivary flow and composition: Reduced salivary flow rates

are associated with active celiac disease, leading to dry mouth

and a burning feeling on the tongue [44].

D. Caries: Several research have shown a higher rate of dental

decay in individuals with celiac patients, likely due to the

susceptibility of hypoplastic enamel to decay and variations in

saliva flow and chemical makeup [44,47].

E. RAS-like oral ulceration: The connection between Recurrent

Aphthous Stomatitis (RAS) and celiac disease remains

controversial, with some studies supporting an association

and others not [48,49]. Ulcers resembling RAS-like ulcers may

be also due to anemia and hematinic deficiencies [50,51].

F. Bleeding tendency: Celiac disease has been linked with

coagulation abnormalities, leading to a higher risk of bleeding

in affected patients. This coagulopathy is primarily caused by

prothrombin abnormalities due to inadequate absorption of

vitamin K [52].

G. Dermatitis herpetiformis: This skin condition, closely

linked to celiac disease, can present with oral lesions,

including erythematous-purpuric macules, erosions, ulcers,

and vesicles on the tongue, buccal mucosa and alveolar ridge

[53]. On a clinical basis, it is difficult to distinguish dermatitis

herpetiformis from other blistering diseases, so histological

and immunofluorescence testing is crucial for diagnosis.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Stomach contents naturally flow back into the esophagus,

typically neutralized and cleared by the body’s protective

mechanisms, which are known as Gastroesophageal Reflux

(GER) [15]. However, in some individuals, this reflux can lead to

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD), identified by symptoms

primarily affecting the esophagus. GERD can also impact other

areas, including the pharynx, larynx, respiratory system, and

oral cavity, known as extra-esophageal syndrome [16]. Common

symptoms include heartburn, sour taste, dysphagia, sore throat,

odynophagia, globus sensation and nausea [15,16,54,55].

Epidemiology: GERD is a prevalent issue worldwide, becoming

increasingly common among both children and adults. It typically

presents in their 30s, with a higher incidence in women [54], and

affects up to 20% of the population in Western Europe and North

America [55].

Etiopathogenesis: The balance of various physiological and

mechanical mechanisms, such as salivary flow, swallowing, and

esophageal peristalsis, typically regulates GER. Disruptions in these

regulatory factors, along with increased stomach acid reflux into

the esophagus and upper gastrointestinal tract, can contribute to

the development of GERD [55].

Oral manifestations:

a. Dental erosion: One of the most prevalent extra-esophageal

effects of GERD, affecting up to 44% of patients [20,23,24]. It

typically impacts the lingual or palatal surfaces of the anterior

teeth [25]. The severity of dental erosion varies, ranging from

mild enamel loss to significant dent in exposure [25].

b. Xerostomia: Dry mouth is a common side effect of medications

used to treat GERD, rather than a direct result of the condition

itself. Proton pump inhibitors, commonly prescribed for GERD,

are known to cause dry mouth [25].

c. Halitosis: While halitosis is primarily linked to certain oral

health issues (such as periodontal disease or tongue coating),

there is a higher risk of bad breath in individuals with GERD.

This may be due to a weakened lower esophageal sphincter,

which allows gases and gastric contents to enter the esophagus,

resulting in foul-smelling breath [56].

d. Mucositis: Mucositis can occur when acidic substances or their

fumes meet the oral mucosa. This typically presents erythema

on the palate and uvula, accompanied by a burning feeling or

discomfort [54]. Sometimes, the damage is visible only under

microscope, without any visible clinical signs or symptoms,

though patients may still report symptoms such as a burning

feeling [54].

e. Other Manifestations: Other reported oral symptoms in GERD

patients include Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis (RAS)-like

ulcers, sour taste, and burning mouth [23,56]. RAS-like ulcers

are likely secondary to anemia or deficiencies in hematinic

nutrients, which are common in GERD patients. Additionally,

some individuals may experience heightened sensitivity in the

oral tissues (hyperesthesia), which are likely caused by local

irritation from gastric reflux./p>

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection

Some studies indicate a potential association between Helicobacter pylori infection and various oral conditions, including recurrent aphthous ulcers, glossitis, and halitosis. The identification of H. pylori bacteria in dental plaque and saliva suggests that the bacterium may contribute to the development of oral lesions, either through direct colonization or because of systemic effects [14,19]. This presence highlights the potential role of H. pylori in oral pathology and underscores the need for further research to establish its significance in oral health and disease.

Other GI disorders and their oral presentations

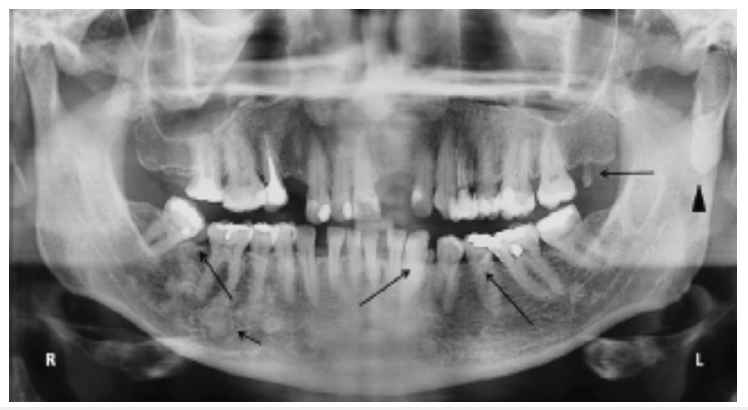

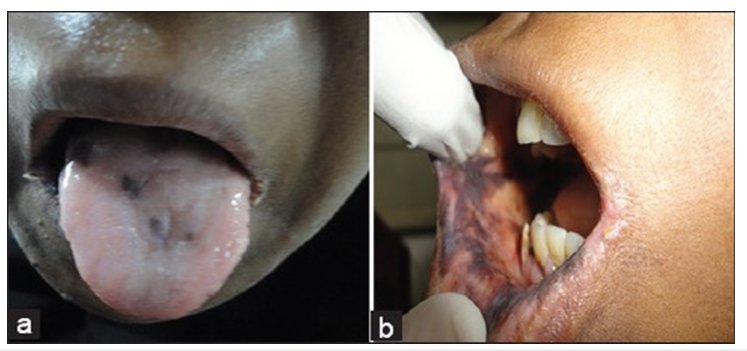

a. Liver cirrhosis-Associated with jaundiced mucosa, petechiae, spontaneous gingival bleeding and glossitis [57,58]. b. Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD)-Linked to recurrent oral ulcers and burning mouth syndrome. Dark erythematous tongue with a slimy yellowish coating, congestion and dilatation of sublingual veins [13,19]. c. Pancreatic disorders-Some cases report xerostomia and taste disturbances due to pancreatic insufficiency [59,60]. d. Gardner’s syndrome: Characterized by the presence of osteomas and various dental anomalies, including odontomas, impacted teeth and supernumerary teeth [10,64] (Figure 5). e. Plummer-Vinson syndrome: Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) may be accompanied by lesions resulting from iron deficiency anemia, including stomatitis, recurrent aphthous stomatitislike ulcerations, angular cheilitis, mucosal pallor and atrophic glossitis [22,29-31] (Figure 6).

Figure 5:Gardner syndrome; Gardner syndrome. Panoramic radiographic a patient. The presence of osteoma in the left condylar region (arrowhead). Note supernumerary teeth in the mandible and maxilla (long arrow). Osseous dysplasia can also be observed throughout the mandibular body (short arrow). Adopted from Pereira et al. [64].

Figure 6:(a) The patient presented with notable atrophy of the tongue, accompanied by angular cheilitis, characterized by inflammation and fissuring at the corners of the mouth. (b) Additionally, marked intraoral pigmentation in Plummer Vinson syndrome. Adopted from Samad et al. [22].

f. Hiatal hernia: Oral manifestations related to GERD and anemia

[21,32,33].

g. Pernicious anemia: Characterized by inflammation of

the tongue (atrophic glossitis), burning tongue sensation

(glossodynia) and ulcers resembling recurrent aphthous

stomatitis (RAS-like ulcerations) [21,26-28].

Discussion

The findings from this review suggest the significant role of oral manifestations in identifying underlying gastrointestinal diseases. In several cases, oral lesions serve as the first clinical signs, necessitating early interdisciplinary collaboration between dentists and gastroenterologists.

Clinical relevance

a. Dentists should remain vigilant in recognizing persistent oral

lesions that do not respond to conventional treatment, as they

may be indicative of a systemic condition [61].

b. The presence of recurrent aphthous stomatitis, cobblestone

mucosa, or unexplained enamel defects should prompt a

referral for gastrointestinal evaluation [62].

c. In patients with GERD, dental erosion may progress despite

good oral hygiene, necessitating both medical and dental

interventions [62].

d. Screening for celiac disease in individuals with unexplained

enamel defects or recurrent ulcers can aid in early diagnosis

and management [63].

Implications for dental management

a. Personalized treatment planning is crucial, considering the

increased risk of bleeding (liver disease), infection (IBD), or

delayed healing (celiac disease) in affected individuals [64].

b. Preventive strategies, such as fluoride application for GERDinduced

dental erosion and proper dietary counseling for

celiac disease, should be incorporated into routine dental care

[64].

c. Dentists should be aware of the potential drug interactions in

patients on long-term GI medications, including corticosteroids

and proton pump inhibitors [64].

Future directions

Despite the growing evidence linking gastrointestinal disorders with oral manifestations, further longitudinal studies are necessary to establish cause-and-effect relationships and develop oral biomarkers for GI diseases. Additionally, raising awareness among healthcare professionals about oral-systemic connection will improve patient outcomes through early intervention and multidisciplinary collaboration [34,35,64].

Conclusion

This review highlights the connection between gastrointestinal diseases and oral health, emphasizing the need for early recognition of oral symptoms. Given that oral lesions often precede systemic signs, dentists perform a crucial part in the early diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal disorders. Although the prevalence of oral manifestations varies among gastrointestinal disorders and is often non-specific (e.g., RAS-like ulceration, stomatitis, burning sensation), these symptoms may appear before the onset of the fundamental condition, potentially aiding in early diagnosis. Collaboration between dental and medical professionals will enhance comprehensive patient care and improve clinical outcomes.

References

- Daley TD, Armstrong JE (2007) Oral manifestations of gastrointestinal diseases. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 21(4): 241-244.

- White SJ, Carey FA (2020) The gastrointestinal system. Muir's Textbook of Pathology, CRC Press, Florida, USA, pp. 231-266.

- Jajam M, Bozzolo P, Niklander S (2017) Oral manifestations of gastrointestinal disorders. J Clin Exp Dent 9(10): e1242-1248.

- Al-Zahrani MS, Alhassani AA, Zawawi KH (2021) Clinical manifestations of gastrointestinal diseases in the oral cavity. Saudi Dent J 33(8): 835-841.

- Lankarani KB, Sivandzadeh GR, Hassanpour S (2013) Oral manifestation in inflammatory bowel disease: A review. World J Gastroenterol 19(46): 8571-8579.

- Pazheri F, Alkhouri N, Radhakrishnan K (2010) Pyo stomatitis vegetans as an oral manifestation of Crohn's disease in a pediatric patient. Inflamm Bowel Dis 16(12): 2007.

- Greenstein AJ, Janowitz HD, Sachar DB (1976) The extra-intestinal complications of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: A study of 700 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 55(5): 401-412.

- Lisciandrano D, Ranzi T, Carrassi A, Sardella A, Campanini MC, et al. (1996) Prevalence of oral lesions in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 91(1): 7-10.

- Salek H, Balouch A, Sedghizadeh PP (2014) Oral manifestation of Crohn's disease without concomitant gastrointestinal involvement. Odontology 102(2): 336-338.

- Boffano P, Bosco GF, Gerbino G (2010) The surgical management of oral and maxillofacial manifestations of Gardner syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 68(10): 2549-2554.

- Korsse SE, Van Leerdam ME, Dekker E (2017) Gastrointestinal diseases and their Oro-dental manifestations: Part 4: Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Br Dent J 222(3): 214-217.

- Lucchese A, Di Stasio D, De Stefano S, Nardone M, Carinci F (2023) Beyond the gut: A systematic review of oral manifestations in celiac disease. J Clin Med 12(12): 3874.

- Li C, Wu Y, Xie Y, Zhang Y, Jiang S, et al. (2022) Oral manifestations serve as potential signs of ulcerative colitis: A review. Front Immunol 13: 1013900.

- Gravina AG, Priadko K, Ciamarra P, Granata L, Facchiano A, et al. (2020) Extra-gastric manifestations of helicobacter pylori infection. J Clin Med 9(12): 3887.

- Ranjitkar S, Kaidonis JA, Smales RJ (2012) Gastroesophageal reflux disease and tooth erosion. Int J Dent 2012: 479850.

- Silva MA, Damante JH, Stipp AC (2001) Gastroesophageal reflux disease: New oral findings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 91(3): 301-310.

- Pace F, Pallotta S, Tonini M, Vakil N, Bianchi Porro G (2008) Systematic review: Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dental lesions. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 27(12): 1179-1186.

- Vinesh E, Masthan K, Kumar MS, Jeyapriya SM, Babu A, et al. (2016) A clinicopathologic study of oral changes in gastroesophageal reflux disease, gastritis and ulcerative colitis. J Contemp Dent Pract 17(11): 943-947.

- Corrêa MC, Lerco MM, Henry MA (2008) Study in oral cavity alterations in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Arq Gastroenterol 45(2): 132-136.

- Talley N (2008) Self-reported halitosis and gastro-esophageal reflux disease in the general population. J Gen Intern Med 23(3): 260-266.

- Jurge S, Kuffer R, Scully C, Porter SR (2006) Mucosal disease series. Number VI. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Oral Dis 12(11): 1-21.

- Samad A, Mohan N, Balaji RS, Augustine D, Patil SG (2015) Oral manifestations of plummer vinson syndrome: A classic report with literature review. J Int Oral Health 7(3): 68-71.

- Limdiwala PG, Shah JS, Parikh SJ, Pillai JP (2023) Oral manifestations in patients with gastro-esophageal reflux disease: A hospital-based case-control study. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol 35(1): 56-60.

- Tan CXW, Brand HS, De Boer NKH, Forouzanfar T (2016) Gastrointestinal diseases and their Oro-dental manifestations: Part 1: Crohn's disease. Br Dent J 221(12): 794-799.

- Kumar KS, Mungara J, Venumbaka NR, Vijayakumar P, Karunakaran D (2018) Oral manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children: A preliminary observational study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 36: 125-129.

- Boukssim S, Chbicheb S (2024) Oral manifestations of vitamin B12 deficiency associated with pernicious anemia: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 121: 109931.

- Chang JY, Wang YP, Wu YC, Cheng SJ, Chen HM, et al. (2015) Hematinic deficiencies and pernicious anemia in oral mucosal disease patients with macrocytosis. J Formos Med Assoc 114(8): 736-741.

- Sun A, Chang JY, Wang YP, Cheng SJ, et al. (2016) Do all the patients with vitamin B12 deficiency have pernicious anemia? J Oral Pathol Med 45(1): 23-27.

- Karthikeyan P, Aswath N, Kumaresan R (2017) Plummer vinson syndrome: A rare syndrome in male with review of the literature. Case Rep Dent 2017: 6205925.

- Silva BS, Souza DP, Fernandes AC, Rodrigues LR, Kujan O, et al. (2025) Manifestations of head and neck cancer in patients with Plummer Vinson syndrome: A Systematic Review. Oral Dis.

- Bakshi SS (2016) Plummer-Vinson syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc 91(3): 404.

- Goodwin ML, Nishimura JM, D Souza DM (2021) Atypical and typical manifestations of the hiatal hernia. Ann Laparosc Endosc Surg 6: 39.

- Durazzo D, Lupi G, Cicerchia F, Ferro A, Barutta F, et al. (2020) Extra-esophageal presentation of gastroesophageal reflux disease: 2020 update. J Clin Med 9(8): 2559.

- Anas M, Ullah I, Sultan MU (2025) Public health interventions targeting maternal nutrition and oral health: A Narrative Review. Jordan J Dent 2(1): 60-67.

- Anas M, Ullah I, Sultan MU (2024) Enhancing pediatric dental education: A response to curriculum shifts. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 26(2): 401-402.

- Ponder A, Long MD (2013) A clinical review of recent findings in the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Epidemiol 5: 237-247.

- Laass MW, Roggenbuck D, Conrad K (2014) Diagnosis and classification of Crohn's disease. Autoimmun Rev 13(4-5): 467-471.

- Aghazadeh R, Zali MR, Bahari A, Amin K, Ghahghaie F, et al. (2005) Inflammatory bowel disease in Iran: A review of 457 cases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 20(11): 1691-1695.

- Atarbashi MS, Lotfi A, Atarbashi MF (2016) Pyo stomatitis vegetans: A clue for diagnosis of silent Crohn's disease. J Clin Diagn Res 10(12): ZD12-ZD13.

- Farmer RG, Easley KA, Rankin GB (1993) Clinical patterns, natural history and progression of ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci 38(6): 1137-1146.

- Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, et al. (2012) Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 142(1): 46-54.

- Pastore L, Campisi G, Compilato D, Lo Muzio L (2008) Orally based diagnosis of celiac disease: Current perspectives. J Dent Res 87(12): 1100-1107.

- Costacurta M, Maturo P, Bartolino M, Docimo R (2010) Oral manifestations of coeliac disease: A clinical-statistic study. Oral Implantol 3(1): 12-19.

- Mantegazza C, Paglia M, Angiero F, Crippa R (2016) Oral manifestations of gastrointestinal diseases in children. Part 4: Coeliac disease. Eur J Paediatr Dent 17(4): 332-334.

- Dahele A, Ghosh S (2001) Vitamin B12 deficiency in untreated celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol 96(3): 745-750.

- Avşar A, Kalayci AG (2008) The presence and distribution of dental enamel defects and caries in children with celiac disease. Turk J Pediatr 50(1): 45-50.

- Cheng J, Malahias T, Brar P, Minaya MT, Green PH (2010) The association between celiac disease, dental enamel defects and aphthous ulcers in a United States cohort. J Clin Gastroenterol 44(3): 191-194.

- Robinson N, Porter SR (2004) Low frequency of anti-endomysia antibodies in recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Ann Acad Med Singap 33(4): 43-47.

- Sedghizadeh PP, Shuler CF, Allen CM, Beck FM, Kalmar JR (2002) Celiac disease and recurrent aphthous stomatitis: A report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 94(4): 474-478.

- Lopez-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Martos N (2014) Hematological study of patients with aphthous stomatitis. Int J Dermatol 53(2): 159-163.

- Halfdanarson TR, Litzow MR, Murray JA (2007) Hematologic manifestations of celiac disease. Blood 109(2): 412-421.

- Nicolas ME, Krause PK, Gibson LE, Murray JA (2003) Dermatitis herpetiformis. Int J Dermatol 42(8): 588-600.

- Vakil N, Van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R (2006) The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: A global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol 101(8):1900-1920.

- Aberg F, Helenius HJ (2022) Oral health and liver disease: Bidirectional associations-A narrative review. Dent J 10(2): 16.

- Carrozzo M, Scally K (2014) Oral manifestations of hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol 20(24): 7534-7543.

- Miulescu R, Balaban DV, Sandru F, Jinga M (2020) Cutaneous manifestations in pancreatic diseases: A review. J Clin Med 9(8): 2611.

- Uc A, Fishman DS (2017) Pancreatic disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am 64(3): 685-706.

- Lockhart PB, Hong CH, Van Diermen DE (2011) The influence of systemic diseases on the diagnosis of oral diseases: A problem-based approach. Dent Clin North Am 55(1): 15-28.

- Awal D, Lloyd TW, Petersen HJ (2014) The role of the dental practitioner in diagnosing connective tissue and other systemic disorders: A case report of a patient diagnosed with type III Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Oral Surg 8(2): 96-101.

- Rashid M, Zarkadas M, Anca A, Limeback H (2011) Oral manifestations of celiac disease: A clinical guide for dentists. J Can Dent Assoc 77: b39.

- Inchingolo AD, Dipalma G, Viapiano F, Netti A, Ferrara I, et al. (2024) Celiac disease-related enamel defects: A systematic review. J Clin Med 13(5): 1382.

- Mozaffari S, Mousavi T, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M (2023) Common gastrointestinal drug-drug interactions in geriatrics and the importance of careful planning. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 19(11): 807-828.

- Plauth M, Jenss H, Meyle J (1991) Oral manifestations of Crohn's disease: An analysis of 79 cases. J Clin Gastroenterol 13(1): 29-37.

- Pereira DL, Carvalho PA, Achatz MI, Rocha A, et al. (2016) Oral and maxillofacial considerations in Gardner's syndrome: A report of two cases. Ecancermedicalscience 10: 623.

© 2025 Muhammad Anas. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)