- Submissions

Full Text

Modern Research in Dentistry

Nasoalveolar Molding- Graysons Technique

Shafees Koya* and Akhter Husain

Department of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopaedics, Yenepoya Dental College, Yenepoya University, India

*Corresponding author: Shafees Koya, Assistant Professor, Department of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopaedics, Yenepoya Dental College, Yenepoya University, Mangalore, Karnataka, India

Submission: October 20, 2017; Published: November 30, 2017

ISSN:2637-7764Volume1 Issue3

Introduction

Since centuries neonatal maxillary orthopaedics is a treatment modality in which distorted and displaced maxillary segments at birth are repositioned by series oforthopaedic appliances to produce a normal appearing maxilla while reducing the cleft space in the alveolus and palate. Nasoalveolar molding got popularised because of its enabled nasal molding capability. Presurgical neonatal nasal remodeling with an infant plate was first described by Dogliotti et al. [1]. The first treatment protocol for nasoalveolar molding (NAM) was described and popularized by Grayson et al. [2]. This technique was different from the previous techniques of infant orthopedics where in a nasal stent was added to the intra oral plate enabling nasal and alveolar molding simultaneously. The combined oral plate and nasal stent produced a nasoalveolar molding appliance. The oral plate is used shortly after birth (approximately a week) and the nasal stent is added when the alveolar cleft is less than 0.5cm. The patient is usually treated with nasoalveolar molding therapy for 3 to 4 months until the alveolar cleft is less than 3mm and the nostril rim on the affected side had been repositioned. When the patient completes nasoalveolar molding therapy, primary lip, alveolar, and nasal surgery is performed.

Objectives

The principle objective of presurgical nasoalveolar molding is to reduce severity of the initial cleft deformity. This enables the surgeon to enjoy the benefits associated with repair of an infant that has a minimal cleft deformity. The goals include achieving lip segments that are almost in contact at rest, symmetrical lower lateral nasal cartilages, up righting of the columella and adequate nasal mucosal lining that permits postsurgical retention of the projected nasal tip. Additional objectives of nasoalveolar molding include reduction in the width of the alveolar cleft segments until passive contact of the gingival tissues is achieved. As reduction of the alveolar gap width is accomplished, the base of the nose and lip segments achieves improved alignment. All these are achieved using a nasal stent, intraoral molding plate, and surgical tape.

In infants with bilateral clefts of the lip, alveolus, and palate, the objective of presurgical nasoalveolar molding includes the nonsurgical elongation of the columella, centring of the premaxilla along the midsagittal plane, and retraction of the premaxilla in a slow and gentle process to achieve continuity with the posterior alveolar cleft segments. Additional objectives include reduction in the width of the nasal tip, improved nasal tip projection, and decrease in the width of nasalalar base.

Procedure

There are many modifications been done to the original Grayson's technique. Figueroa et al. [3], Iino Mitsuyoshi et al. [4], Cenkdoruk & Banu kilic [5], Ricardo et al. [6], Amornpong et al. [7], Abida Ijaz et al. [8], Quan Yu et al. [9] are some of them who tried to improvise the technique.

Grayson’s Technique

Figure 1: Making of impression in a cleft baby in inverted position.

A heavy-bodied impression material is used to take the initial impression as soon after birth as possible [10]. Impression is taken with the infant in the lap of the guardian in an inverted position (Figure 1). Once the impression material is set, the tray is removed and the mouth is examined for residual impression material that may be left behind. A cast or model of the alveolar anatomy is made by filling the impression with a dense plaster material (dental stone). The molding plate is fabricated on the dental stone model. It is made of hard clear acrylic and lined with a thin coat of soft denture material. Care is taken to reduce the border of the plate in the labial frenum attachments and other areas that may be likely to ulcerate. A 5mm diameter hole is made in the centre of the acrylic palatal vault to provide an airway if the posterior border of the plate drops down onto the tongue.

Parents are instructed to keep the plate in full time, and to take it out for cleaning as needed, at least once a day. Initially, it may take longer to feed the infant with the plate in place, but the child quickly adjusts and parents report that they soon will not eat without it (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Patient sleeping comfortably with the plate.

The appliance is secured extra orally to the cheeks, bilaterally by surgical tapes, which have an orthodontic elastic band at one end. The elastics loop over a retention arm extending from the anterior flange of the plate.

Figure 3: Patient with the lip taping and NAM appliance with nasal stent.

The retention arm is positioned approximately 40° down from the horizontal plane to achieve proper activation and to prevent unseating of the appliance from the palate (Figure 3). The tapes and elastics are changed once a day. Appointments should be given every 2 Weeks to modify the molding plate to guide the alveolar cleft segments into the desired position. Care should be taken not to add the nasal stent before achieving laxity of the alar rim, as an increase of the nostril circumference may result. Only one retention arm is attached to the appliance for treatment of the unilateral cleft patient. Parents are instructed to place tapes to approximate the cleft lip segments. The tape should be applied at the base of the nose (nasolabial angle) and not low on the lip near the vermillion border. The tape should be applied to the noncleft side first, then pulled over and adhered to the cleft side, trying to bring the philtrum and columella to the midline.

Figure 4: NAM plate with nasal stent added.

When the cleft alveolar gap is reduced to 5mm or less, the nasal stent is added. The stent is made of .036 gauge round stainless- steel wire and takes the shape of a "swan neck” with a kidney beanshaped nasal bulb (Figure 4). The kidney bean-shaped nasal bulb has 2 parts: a relatively larger upper lobe that lies beneath the alar dome and a lower lobe that lies just beneath the nostril rim. Incremental addition of soft denture reline material to the upper lobe and controlled activation of the upper neck portion of the nasal stent support and gently mold the collapsed alar dome, which is clinically reflected by its mild tissue blanching.

Appliance Adjustments

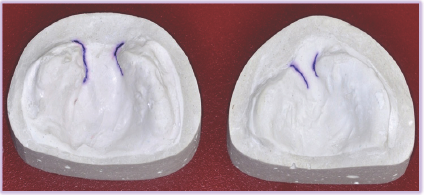

The baby is seen weekly to adjust the moulding plate to bring the alveolar segments together. These adjustments are made by selectively removing the hard acrylic and adding the soft denture base material to the moulding plate. No more than 1mm of modification of the moulding plate should be made at one visit (Figure 5 & 6).

Figure 5: Addition of soft tissue liner.

Figure 6: Relined NAM plate.

The alveolar segments should be directed to its final and optimal position. Care must be taken to prevent the soft denture material from building up on the height of the alveolar crest as this will prevent complete seating of the moulding plate.

Instructions for the Parents

a. Parents should be motivated & educated properly.

b. They should be instructed to keep the plate in full time, and to take it out for cleaning as needed, at least once a day.

c. Tapes and elastics are changed once a day.

d. Ask to apply baby cream over cheeks while changing tapes.

e. They are asked to examine the child's mouth regularly for any ulceration.

Duration of Therapy

NAM therapy is done till the objectives are met. Surgical closure of the lip and nose is performed from 3-4 months of age [11-14]. Bilateral cleft patients tend to take one to two additional months to achieve presurgical clinical objectives. The duration of moulding therapy could also vary depending on the severity of the initial cleft deformity.

Case Report

Figure 7: Pre, with NAM % Post surgery comparison extra oral photographs of a unilateral cleft lip & palate case.

Figure 8: Pre and Post NAM comparison of the cast in the unilateral cleft lip & palate case.

Patient named Hafeefa (Figure 7 & 8) aged 20 days reported to the craniofacial centre of our university with complete unilateral cleft lip and palate in the right side. On measurement she showed 10mm cleft in the lip and 13mm cleft between the 2 segments of the palate. NAM therapy was initiated immediately and the appliance was discontinued once the cleft of the alveolus was reduced to 3-4mm along with sufficient amount of lip and nasal molding. Patient was recalled every 14 days and adjustments were made to the appliance allowing molding of alveolus and nose. Post NAM good amount of molding of nose, lip and alveolus was obtained. This was followed by cheiloplasty in the centre for craniofacial anomalies, Yenepoya University. Nasal molding can be noticed by increased columellar length and improved nostril form in the submental view of post NAM. Post-surgery result was excellent with a good lip and columella. Approximation of the alveolus can be noticed in the study model.

Benefits

a. Since the cleft deformity is reduced in size before surgery; a better and more predictable surgical result can be expected.

b. It reduces the number of surgical revisions for excessive scar tissue, oronasal fistulas, and nasal & labial deformities.

c. Improved long-term nasal esthetics & reduced number of nasal surgical procedures.

d. Permanent teeth have a better chance of eruption due to the approximation of alveolus.

Conclusion

Long-term studies of NAM therapy indicate that the change in the nasal shape is stable with less scar tissue and better lip and nasal form [15-19]. Even though NAM pauses disadvantage of regular appointments and cost factors, the benefits surpass the drawbacks. With proper training and clinical skills, NAM has demonstrated tremendous benefit to the cleft patients as well as to the surgeon performing the primary repair.

References

- Dogliotti PL, Bennun RD, Losoviz E, Ganiewich E (1991) Non-surgical treatment of nasal deformity in the cleft patient. Rev Ateneo Arg Odont 27: 31-35.

- Grayson BH, Cutting CB, Wood R (1993) Preoperative columella lengthening in bilateral cleft lip and palate. Plast Reconstr Surg 92(7): 1422-1423.

- Figueroa, Reisberg DJ, Polley JW, Cohen M (1996) Intra oral modification to retract the premaxilla in patients with bilateral cleft lip. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 33(6): 497-500.

- Mitsuyoshia I, Masahiko W, Masayuki F (2004) Simple modified preoperative nasoalveolar moulding in infants with unilateral cleft lip and palate. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 42(6): 578580.

- Doruk C, Kilic B (2005) Extraoral nasal molding in a newborn with unilateral cleft lip and palate: a case report. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal 42(6): 699-702.

- Bennun R, Figueroa A (2006) Dynamic presurgical nasal remodeling in patients with unilateral and bilateral cleft lip and palate: modification to the original technique. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal 43(6): 639-648.

- Vachiramon AT, Groper JN, Gamer S (2008) A rapid solution to align the severely malpositioned premaxilla in bilateral cleft lip and palate patients. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal 45(3): 229-231.

- Abida I, Arsalah R, Junaid I (2010) Nasoalveolarmolding of bilateral cleft of the lip and palate infants with orthopaedic ring plate. JPMA 60(7): 527-531.

- Quan Yu, Gong X, Wang GM, Yu ZY, Qian YF, et al. (2011) A novel technique for presurgical nasoalveolar molding using computer-aided reverse engineering and rapid prototyping. J Craniofac Surg 22(1): 142-146.

- Grayson BH, Cutting CB (2001) Presurgical nasoalveolar orthopaedic molding in primary correction of the nose, lip, and alveolus of infants born with unilateral and bilateral clefts. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 38(3): 193-198.

- Cutting CB, Grayson BH, Brecht LE, Santiago P, Wood R, et al. (1998) Presurgical columellar elongation and primary retrograde nasal reconstruction in one-stage bilateral cleft lip and nose repair. Plast Reconstr Surg 101(3): 630-639.

- Cutting CB, Grayson BH (1993) The prolabial unwinding flap method for one-stage repair of bilateral cleft lip, nose, and alveolus. Plast Reconstr Surg 91(1): 37-47.

- Cutting CB (1994) Cleft nasal reconstruction. In: Rees T, Trenta GL (Eds.), Aesthetic plastic surgery, Saunders, Philadelphia, USA, pp. 497-532.

- Cutting CB, Bardach J, Pang R (1989) A comparative study of the skin envelope of the unilateral cleft lip nose subsequent to rotation- advancement and triangular flap lip repairs. Plast Reconstr Surg 84(3): 409-417.

- Bennun RD, Langsam AC (2009) Long-term results after using dynamic presurgical nasoalveolar remodeling technique in patients with unilateral and bilateral cleft lips and palates. The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery 20(1): 670-674.

- Ingrid B, Wojciech D, Stephen W, Cutting CB, Grayson B (2009) Nasoalveolar molding improves long-term nasal symmetry in complete unilateral cleft lip-cleft palate patients. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 123(3): 1002-1006.

- Clark S, Teichgraeber J, FleshmanR, Chavarria C, Kau C, et al. (2011) Long-term treatment outcome of presurgical nasoalveolar molding in patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate. The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery 22(1): 333-336.

- Garfinkle JS, King TW, Grayson BH, Brecht LE, Cutting CB (2011) A 12- year anthropometric evaluation of the nose in bilateral cleft lip-cleft palate patients following nasoalveolarmolding and cutting bilateral cleft lip and nose reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 127(4): 1659-1667.

- Liou EJW, Subramanian M, Chen PK, Huang CS (2004) The progressive changes of nasal symmetry and growth after nasoalveolarmolding: a three-year follow-up study. Plast Reconstr Surg 114(4): 858-864.

© 2017 Shafees Koya, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)