- Submissions

Full Text

Modern Concepts & Developments in Agronomy

Long-Time Fire Effects in Native Woody Species from Argentine Chaco Region

Sandra J Bravo*

Faculty of Forest Sciences, Argentina

*Corresponding author: Sandra J Bravo, Faculty of Forest Sciences, Santiago Del Estero, Argentina

Submission: September 15, 2022;Published: September 23, 2022

ISSN 2637-7659Volume11 Issue 4

Introduction

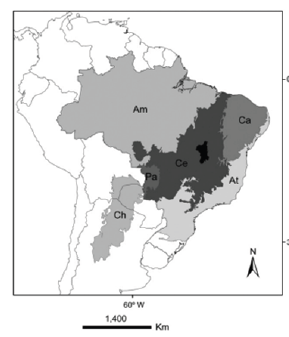

Chaco region is the second forest area in South America after Amazonia that forms a diagonal of arid to semiarid vegetation formations with the Caatinga and the Cerrado from Brazil (Werneck 2011). The Chaco region contains tree species of ecological and productive importance and several endemic species that becoming a high-priority conservation area. This region comprises a mosaic of seasonally dry forests, grasslands, savannas, and shrublands [1-3]. The biomass of native vegetation follows the annual rainfall model reaching higher NDVI values during summer months [4]. Fire season extends from Abril to October, and from pre-Colombian times, both aborigines and farmers burnt grasslands and savannas to promote the growth of grasses [5]. The fires are considered a common disturbance in grasslands and savannas of the Chaco region, despite their origin being mainly anthropogenic [6,2]. Chaco savannas and pyrogenic grasslands need fire recurrence to maintain their species composition and structure, and these areas support the native birds and mammal populations with high conservation priority [3]. Grassland or savanna fires are incoming to forests when unusual environmental conditions, such as extreme droughts combined with high temperatures and low moisture content of fuels [5] (Figure 1).

Figure 1:Georeferenced localization of Chaco region (ch), Cerrado (Ce) and Caatinga (Ca) relative to other South American biomes (Amazonia Am, Atlantic Forest (At) and Pantanal (Pa). taken from Werneck (2011).

The native vegetation of forests has remarkable resilience to fires through the resprouting strategy [7-9], whereas sexual regeneration seems to be difficult due to the hardness of environmental conditions of the Chaco region and the disturbance patterns [10] and Ibáñez-Moro et al. 2021. On the other hand, the forestry management plans in the Chaco region include silvopastoral systems in which prescribed fires are used to reduce the shrubby stratum Kunst et al. [5]. Wildfires combined with prescribed fires, unplanned forestry exploitation, overgrazing, and mechanical removal of the understory strongly altered structure, provoke changes in species composition of shrubby strata and ecosystems services provision (Figure 2); [2,3,6]. An aspect scarcely considered yet is the effect of wildfires and prescribed fires on the health of forests and secondary mortality of both tree and shrub species. Wildfires can produce tree mortality during the event or generate fire wounds on wood called scars or marks that constitute an access window to pathogens such as fungi and insects after fires (Figure 3); [11,12,6]. The process of fire scars and marks formation has been described for native tree species of Argentina (Medina, 2003; [13-16]) but their long-time effect on health and tree mortality has not been analyzed yet. The formation of decolored wood, white and brown rots, and insect galleries on the bole and shoots are the signals often observed in burnt trees and shrubs (Figure 3). The compartmentalization of fire wounds and aptitude for healing is greater among tree species than shrubby species [13]. Among anatomical responses to fire damage have mentioned the increase in parenchyma proportion and the diminishing in vessels and fibber proportion, which could be related to higher susceptibility to pathogens, and the deterioration of health conditions after fires [12-17].

Figure 2:Chaco region forest with mechanical removal of shrubby stratum (A). Fire wound in Schinopsis lorentzii (Anacardiaceae) (B).

Figure 3:Altered wood by fire scar and insect galleries in Prosopis nigra (Fabaceae) (A). White and brown rots and Fusarium species attack in Aspidosperma quebracho-blanco (Apocynaceae) wood (B).

Short-time post-fire evaluations (six months) indicated a low mortality percentage (<10%) after experimental fires among the most representative tree species such as Aspidosperma quebracho- Blanc, Schinopsis lorentzii and Sarcomphalus mistol, even among pole-sized individuals [7]. Similar results were obtained after experimental burns in shrubby species such as Senegalia gilliessii, Schinus fasciculatus and Celtis erhenbergiana [8]. The main tree native species of Chaco have high-density wood and good technological properties with potential for industrial use [18]. The presence of fire scars diminishes the wood volume suitable for higher value uses, which limits the exploitation profit. The law regulating native forest exploitation in the Chaco region establishes a minimum cutting diameter of 35cm diameter because higher diameter individuals of the most forestry valuable species usually present regular or poor healthy state. Therefore, ecological and economic factors justify the study of the fire effects on tree species from Chaco region forests. This information could contribute to fitting the regimes of prescribed fires in forests with more sustainable criteria, improving the potential of native trees for higher value uses.

Argentina needs international cooperation and to participate in academic and technological networks to carry out the abovementioned research line. In the current scenery of climate change, an increasing fire frequency is expected. This fact could become the native Chaco forests into a highly susceptible vegetation unit since accentuated dryness and higher average temperatures in fire season are considered possible. These environmental conditions could hamper the recruitment from the soil seed banks [19], limit the genetic variability, and reduce the vegetative regeneration by resprouts since they are unfavorable for plant and seedlings’ growth [10]. Therefore, the conservation of Chaco region forests requires more studies about the intermediate to a long-time fire effect to accurate its significant role in global ecosystem services.

References

- Fernández PD, Baumann M, Baldi G, Natalia BR, Bravo S, et al. (2020) Grasslands and open savannas of the dry Chaco. Encyclopedia of the World's Biomes, pp.562-576.

- Loto D, Bravo S (2020) Species composition, structure and functional traits in Argentine Chaco forests under two different disturbance histories. Ecological Indicators 113: 106232.

- Coria D, Kunst C, Bravo SJ (2021) A contribution to the understanding of the woody encroachment of grasslands/savannas from South American Semiarid Chaco. Ecología Austral.

- Zerda H, Tiedemann J (2010) Temporal dynamics of the NDVI of the forest and natural grassland in the Dry Chaco of the Province of Santiago del Estero, Argentina. Ambiência Guarapuava 6(1):13-24.

- Kunst C, Bravo S, Ledesma R, Navall M, Anríquez A, et al. (2014) Ecology and management of the dry forests and savannas of the western Chaco region, Argentina. In Dry Forests: Ecology, Species Diversity and Sustainable Management.

- Bravo S (2010) Anatomical changes induced by fire-damaged cambium in two native tree species of the Chaco region, Argentina. IAWA Journal 31(3): 283-292.

- Bravo S, Kunst C, Leiva M, Ledesma R (2014) Response of hardwood tree regeneration to surface fires, western Chaco region, Argentina. Forest Ecology and Management 326: 36-45.

- Ledesma R, Kunst C, Bravo S, Leiva M, Lorea L, et al. (2018) Developing a prescription for brush control in the Chaco region, effects of combined treatments on the canopy of three native shrub species. Arid Land Research and Management 32(3).

- Jaureguiberry P, Cuchietti A, Gorné LD, Bertone GA, Díaz S (2020) Post-fire resprouting capacity of seasonally dry forest species - Two quantitative indices. Forest Ecology and Management 473: 118267.

- Lipoma L, Cabrol D, Cuchietti A, Enrico L, Gorné L, et al. (2021) Low resilience at the early stages of recovery of the semi-arid Chaco forest-Evidence from a field experiment. Journal of Ecology 109(9): 3246-3259.

- Bravo S, Kunst C, Gimenez A, Moglia G (2001a) Fire regime of an Elionorus muticus Spreng. savanna, western Chaco region, Argentina. International Journal of Wildland Fire 10(1): 65-72.

- Bravo S, Giménez A, Moglia J (2001b) Effects of fire on the wood of Prosopis alba Griseb. and Prosopis nigra (Griseb.) Hieron, Mimosaceae. Bosque 22(1): 51-63.

- Bravo S (2006) Fire regime in a Western Chaco savannah and its morphological effects on woody species. Doctoral Thesis, Faculty of Natural Sciences, National University of Tucumán, Argentina, p. 117.

- Bravo S, Giménez A, Moglia J (2006) Anatomical characterization of the log and evolution of growth in specimens of Acacia aroma and Acacia furcatispina in the Chaco Region, Argentina. Bosque 27(2): 146-154.

- Bravo S, Kunst C, Grau R (2008) Suitability of the native woody species of the Chaco region, Argentina, for use in dendroecological studies of fire regimes. Dendrochronologia 26(1): 43-52.

- Bravo S, Kunst C, Grau R, Aráoz E (2010) Fire-rainfall relationships in Argentine Chaco savannas. Journal of Arid Environments 74(10): 1319-1323.

- Bravo S, Bogino S, Leiva M, Lepiscopo M, Cendoya M, et al. (2021) Wood anatomy, fire wounds and dendrochronological potential of Prosopis pugionata (Fabaceae) in arid argentine Chaco. IAWA Journal.

- Giménez A, Moglia J (2003) Trees of the Argentine Chaco. Guide for dendrological reconnaissance. Editions Faculty of Forest Sciences, National University of Santiago del Estero and Secretariat of Environment and Sustainable Development, Ministry of Social Development of the Nation, p. 307.

- Ocampo-Zuleta K, Bravo SJ (2019) Recruitment of woody species in tropical forests wildland fires: an overview. Ecosistemas 28(1): 106-117.

© 2022 Sandra J Bravo. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)