- Submissions

Full Text

Modern Concepts & Developments in Agronomy

Major Weeds of Ecuador. III. Plantains

Ricardo Labrada*

Ex-FAO Technical Officer, Plant Protection Service, Rome, Italy

*Corresponding author:Ricardo Labrada, Ex-FAO Technical Officer, Plant Protection Service, Rome, Italy

Submission: June 23, 2021Published: July 23, 2021

ISSN 2637-7659Volume9 Issue 2

Abstract

Plantain (Musa paradisíaca or Musa AAB) is a tropical fruit cultivated in Canton El Carmen, Ecuador in 41650ha. Local population of Ecuadorian Coast and Eastern part of the country consume its fruit cooked or also raw when it is ripe. One of the constraints to its production is weed incidence, which reduces crop yields and compels farmers to spend on weeding practices throughout the year. Knowledge of weed species with the highest frequency/abundance and the factors that determine their presence in the crop is a way to better design weed management strategy. A weed survey was carried out in in 135ha of plantains during the period of September 2014 and May 2015. Half of the fields checked during winter or rainy period (December-May), while the rest during summer or dry season (June to November). Selected fields were plantations of var. Barraganete mainly planted in rows spaced 3m and 1 or 1,5m between plants on of medium-textured soils, aerated, with good water retention and medium fertility. Fertilization of the plantations was with NPK formula 10-30-10 at unknown rates. Weed cover was visually assessed using a scale 0-5, where 1- up to 5% weed cover and 4-more than 50%. These values were processed to determine Absolute and Relative Frequencies, average weed cover and finally Severity Infestation (SI). Field evaluations resulted in grand total 44 weed species belonging to 22 families. Overall weed cover was an average of 2,5 during rainy period, where perennial Geophila macropoda (Ruiz & Pav.) DC. is the prevailing species. Total weed cover was 0,35 during dry period, where the prevailing species were grasses R. cochinchinensis and Panicum trichoides Sw., and several dicots. Weed flora changes according to herbicide use in both seasons, but G. macropoda is again the prevailing species in paraquat-treated fields during the rainy season and in glyphosate-treated and hand-weeded areas during dry season. The result suggests the convenience to evaluate G. macropoda as possible cover to smother weeds in plantains of El Carmen combined with other control measures.

Introduction

The Canton “El Carmen”, called the Golden Gate of Manabí, is located in the coastal region of Ecuador in an extensive plain crossed by the Suma River, in the foothills of the Western Mountain Range of the Andes, at an altitude of 236 meters above sea level. Tropical savanna climate characterizes this area with annual rainfall of more than 2000 mm, of which 90% corresponds to the rainy season (January-June), and an average temperature of 23 °C.

Plantain (Musa paradisíaca or Musa AAB) is a tropical fruit relative to banana also originated in Southwest Asia, it is a staple in the diet of the Ecuadorian population, especially the inhabitants of the Ecuadorian Coast and Eastern part of the country. Its fruit contains less sugar and more starch, usually consumed cooked or also raw when it is ripe. In El Carmen this crop is cultivated in 41 650ha. The main varieties are valuable Barraganete and to a lesser degree Harton. Main exports are to the USA and to the south of Colombia [1].

Crop management in plantains mainly consists of weeding and desuckering, deleafing is common in areas affected by black sigatoka disease, fertilization is not often practiced in plantations, and pest control is hardly done. It is for this reason that the potential yields are rarely achieved [2].

One of the major constraints to the plantain production is weed incidence, which affects the crop shortly after its planting, and may reduce yields in already established plantations. In El Carmen hand- weeding is the most common control method, but some farmers also use foliar-applied herbicides without any particular system and/or schedule.

The best way to control weeds is through previous knowledge of those species with the highest frequency/abundance and the factors that determine their presence in the crop during the two seasons of the year (dry and rainy) in the coastal zone of Ecuador. This information helps to integrated control measures with an adequate expenditure of the farmer’s available resources. The present study conducted throughout the 2014 dry period and the 2015 rainy period in plantain of El Carmen focused this purpose.

Material and Methods

A weed survey was carried out in 135 ha of plantains during the period of September 2014 and May 2015. Half of the fields checked during winter or rainy period (December-May), while the rest during summer or dry season (June to November). Selected fields were plantations of var. Barraganete mainly planted in rows spaced 3 m and 1 or 1,5m between plants on of medium-textured soils, aerated, with good water retention and medium fertility. Fertilization of the plantations was with NPK formula 10-30-10 at unknown rates.

Visual evaluation of weed cover was conducted using the same scoring system (see below) and data processing reported previously [3]. This time field route was going in two diagonal crossing directions of each field. Evaluation consisted of the cover of each species present and the total weed cover. Sites chosen for evaluation were 8-12 depending on the total area of each field.

Scale-cover

0- 0 weeds

1-1-5%

2- 6-25%

3- 26-50%

4- More than 50%.

Data processed to determine Absolute Frequency (FA), i.e. the number of times each species was found in each site, and Relative Frequency (F) in %:

F=FA/no. sites in each field infested by a species x 100

Then with ΣI- Sum of the cover values and its average IM:

Im = ΣI/N

Where N is the number of fields infested by any species

Finally, Severity Infestation (SI) as:

SI=F*IM

Obtained SI results were grouped in major weeds in each season (rainy and dry) as well as plantations receiving single treatments of either paraquat (1,1’-dimethyl-4,4’-bipyridinium dichloride) or glyphosate (N-(phosphonomethyl)glycine) or hand-weeding.

Result and Discussion

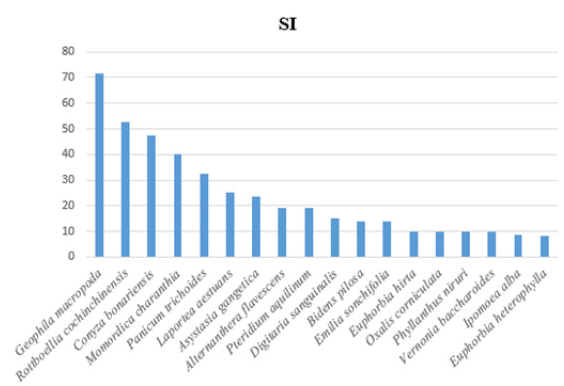

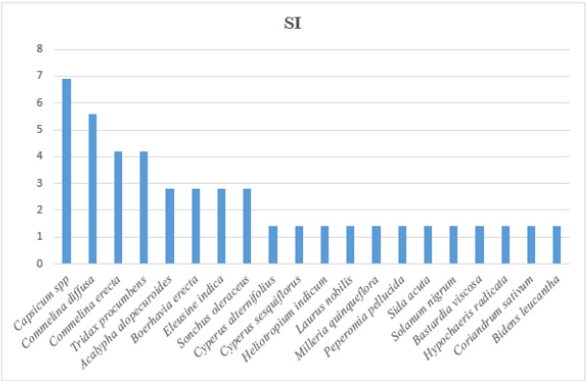

Field evaluations resulted in grand total 44 species belonging to 22 families. Prevailing species were dicots of C3 photosynthesis, but a few grasses were present in spots with lack of plantain leaf shade (Figures 1 & 2).

Figure 1:Abundant species in plantains of El Carmen.

Figure 2:Less abundant weed species in plantains of El Carmen.

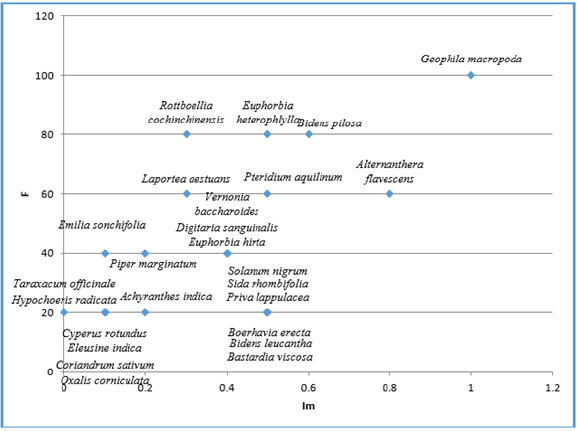

Overall weed cover was an average of 2,5 in inspected fields during rainy period, where perennial Geophila macropoda (Ruiz & Pav.) DC. is the prevailing species (Figure 3). This plant grows with slender creeping stems rooting at the nodes under plantain leaf shade. It also has fibrous roots. The other plants present with high SI are annual grass Rottboellia cochinchinensis (Lour.) Clayton, and broad-leaved Bidens pilosa L., Alternanthera flavescens (Mart.) Kunth, Laportea aestuans (L.) Chew, Euphorbia heterophylla L., and common bracken Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn. Some other species show a medium SI values, such as annual grass Digitaria sanguinalis (L.) M. Scop, and broad-leaved Emilia sonchifolia (L.) DC ex Wight, Vernonia baccharoides Kunth and Euphorbia hirta L.

Figure 3:Prevailing weeds in plantains during the rainy (winter) period.

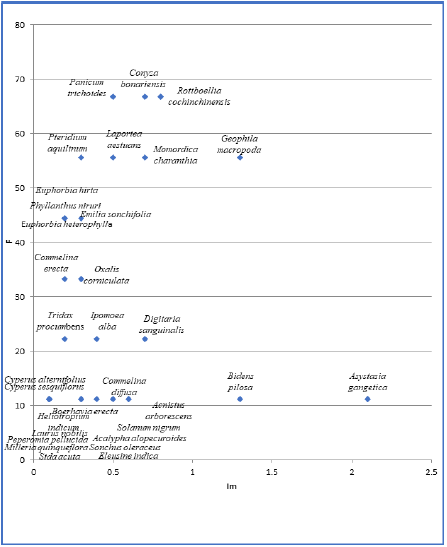

Total weed cover was only 0,35 during dry period. The weed stand and composition differ from the ones recorded during rainy season (Figure 4), where two grasses appear among the prevailing plants, such as R. cochinchinensis and Panicum trichoides Sw., as well as dicots Conyza bonariensis (L.) Cronquist, G. macropoda, L. aestuans, annual climbing Momordica charanthia L., and common bracken. Other plants as E. hirta, E. heterophylla, Phyllanthus niruri L. and E. sonchifolia show medium SI values.

Figure 4:Prevailing weeds in plantains during the dry (summer) period.

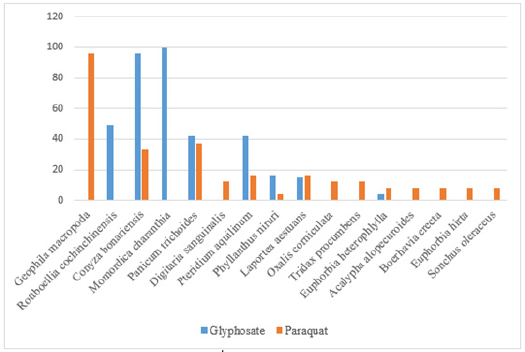

Farmers of El Carmen eventually uses herbicides once a year, such as glyphosate or paraquat, mostly applied during rainy season. Others only rely on hand weeding. Weed composition varies according to herbicide use. G. macropoda stand is high with paraquat application during the rainy season (Figure 5). Conversely R. cochinchinensis, M. charanthia, C. bonariensis and P. aquilinum show high SI values in areas treated with glyphosate.

Figure 5:Weed SI according to herbicide use in plantains during rainy season.

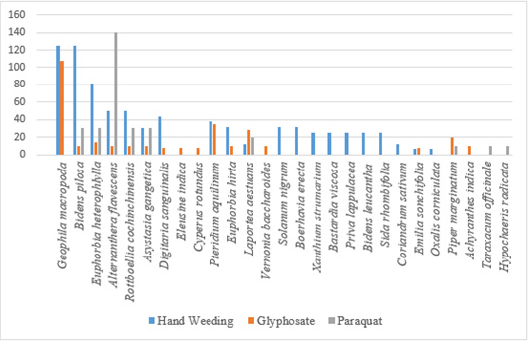

One can expect to have the same weed stand during the dry season. However, A. flavescens, not recorded during rainy period, shows the highest SI value in paraquat-treated fields (Figure 6), while G. macropoda did the same with the application of glyphosate or hand weeding in the fields. B. pilosa and E. heterophylla were more abundant in hand-weeded fields.

Figure 6:Weed SI according to herbicide use in plantains during dry season.

R. cochinchinensis and A. gangetica show medium SI values in fields treated with either paraquat or glyphosate. R. cochinchinensis stand should not be underrated; it is a C4 photosynthesis plant susceptible to shade, so its presence is an indicator of infested spots by low dense plantain leaf canopy probably due to intense sigatoka disease infection. The stand of C. bonariensis in fields treated with glyphosate is not new. Several authors [4-7] have reported glyphosate-resistant biotypes of this plant and other species of the same genus, but it is difficult to assert the existence of such biotypes due to the lack of systematic herbicide application in El Carmen. Repeated glyphosate use brings about problems of resistance. Therefore, a relevant test of resistance is pertinent. The lack of schedule for the use of the already-mentioned herbicides makes difficult to determine a pattern of the weed composition in plantains. Fields have shown a variable weed cover in both seasons. Although weed abundance was much lower during rainy season, none of the fields show outstanding weed control.

The root system of Musaceae plants is shallow, hence any weeding practice should avoid harm it [8]. Annually four handweeding operations are required in established plantains or bananas fields to obtain high yields [9]. This situation changes when it is a weed control in a new plantation, where weeding is carried out within 7-9 months after planting [10].

The solutions to the problem of weeds has been the use of herbicides, initially with foliar-applied paraquat, later with systemic glyphosate. Herbicides became a suitable alternative to reduce weed stand and save farmers’ labor, but at present, there are concerns about the human safety of both compounds. Breathing in paraquat may cause lung damage and can lead to a disease called paraquat lung [3]. It also causes damage to the body when it touches the lining of the mouth, stomach, or intestines. In the case of glyphosate, its repeated application during the last three decades also causes serious health consequences in food, water and air [1].

The use of soil-acting pre-emergence herbicides, such as diuron (1,1-dimethyl, 3-(3’,4’-dichlorophenyl) urea) and simazine (1,3,5-Triazine-2,4-diamine, 6-chloro-N-ethyl-N’-(1-methylethyl) could be options [11]. Although these herbicides are not leachable, slightly uneven relief in the fields of El Carmen is not suitable for the use of such compounds, which may accumulate in soils.

Therefore, the most convenient option for weed control is the use of cover crops, which is recommended by various authors for bananas and plantains plantations [6,8,12]. The main finding in this study has been the predominance of G. macropoda in different areas even in herbicide-treated fields. Cover of this plant reduces erosion in all soil types in banana plantations of Limón in Costa Rica and is useful for weed smothering; it also reduces the reliance on herbicides for weed control [13]. In Ecuador G. macropoda seems to be useful as cover in cocoa plantations since the plant is rich in macro elements (NPK) and stimulates bacteria population growth in soil [5]. However, more research is required to determine the usefulness of this plant as cover for suppressing weeds [14-18]. In plantain areas of Rocafuerte in Ecuador other than El Carmen, some stand of G. macropoda treated with paraquat showed scorched and chlorotic leaves, a sign of tolerance to this herbicide. G. macropoda may well prevent part of weed infestation possibly complemented with other weeding operations.

A major emphasis on weed management in plantains of El Carmen may bring about increased crop yields and net return of the produce.

Conclusion

Results clearly indicate the need to study and validate Geophila macropoda cover for smothering weeds. Such a cover may also stimulate growth of bacterial population in soil as to prevent problems of erosion.

Studies of the use of alternative foliar and soil-acting herbicides in plantains of El Carmen should be carried out with a risk assessment of possible environmental problems and likely effects on human being.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to show his appreciation to Engs. Julio Alberto Mero, Jefferson Bertín Vélez and FENAPROPE (Group of Plantain Producers of El Carmen) for their support and guidance in selecting the fields for weed evaluation; to Eng. María Fernanda Santillán and Ms Marlene Labrada for assistance in weed identification and data processing, respectively.

References

- Anon (2015) 15 Health problems linked to Monsanto's roundup. Ecowatch.

- Kasasian L, Seeyave J (1968) Chemical weed control in bananas-a summary of eight years' experiments in the West Indies. In: Proceedings of the 9th British Weed Control Conference, Brighton, UK, pp: 768-773.

- Labrada R (2021) Major weeds of Ecuador. I. Rice. EC Agriculture 7(2): 18-23.

- Cañizares G, Fabian B, Villafuerte Vargas MA (2021) Geophila macropoda como alternativa de cobertura vegetal en plantaciones de cacao (Theobroma cacao ), BSc. Thesis, Cotopaxi University, La Maná, Ecuador, p. 62.

- Fouré E, Picq C, Frison E (1999) Bananas and food security: International symposium, Douala, Cameroon.

- Travlos I, Chachalis D (2010) Glyphosate-resistant hairy fleabane (Conyza bonariensis) is reported in Greece. Weed Technology 24(4): 569-573.

- Urbano JM, Benjumea Ana B, Vanessa T, León JM (2007) Glyphosate-resistant Hairy Fleabane (Conyza Bonariensis) in Spain. Weed Technology 21(2): 396-401.

- Murillo J, Méndez Estrada VH, Brenes Prendas S (2016) Efecto de Geophila macropoda (Rubiaceae) como arvense de cobertura en la erosión hídrica en bananales de Guápiles, Limón, Costa Rica. UNED Research Journal 8(2): 217-223.

- Anon (2021) Paraquat poisoning. Medline plus, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, D.C., USA.

- Fongod AGN, Focho DA, Mih AM, Fonge BA, Lang PS (2010) Weed management in banana production: The use of Nelsonia canescens (Lam.) Spreng as a non-leguminous cover crop. African Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 4(3): 167-173.

- Tixier P, Lavigne C, Alvareza S, Gauquier A, Blanchard M, et al. (2011) Model evaluation of cover crops, application to elevens pecies for banana cropping systems. European Journal of Agronomy 34(2): 53-61.

- Rodríguez R, Martell M (1987) Período crítico de competencia de las malezas en el cultivo del plátano (Musa spp). Agrotecnia de Cuba 19(2): 13-23.

- Aves C, Broster J, Weston L, Gill GS, Preston C (2020) Conyza bonariensis (flax-leaf fleabane) resistant to both glyphosate and ALS inhibiting herbicides in North-Eastern Victoria. Crop and Pasture Science 71(9): 864-871.

- Dorel M, Tixier P, Dural D, Zanoletti S (2011) Alternatives aux intrants chimiques en culture bananiè Innovations Agronomiques 16: 1-11.

- (1971) Pest control in bananas. Feakin SD (Ed.), PANS Manual No. 1. PANS, 56 Gray's Inn Road, London, UK, p.128.

- Kumar V, Jha P, Jhala AJ (2017) Confirmation of glyphosate-resistant horseweed (Conyza canadensis) in Montana cereal production and response to post herbicides. Weed Technology 31(6): 799-810.

- Simmonds NW (1959) Bananas. Longmans, Londres, R.U., UK, p. 466.

- Terry PJ (1992) Weed management in bananas and plantains. In: “Weed Management for Developing Countries”, Labrada R, Parker C, Caseley JC (Eds.), FAO Plant Production and Protection Paper, 120: 311-315.

© 2021 Ricardo Labrada. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)