- Submissions

Full Text

Modern Concepts & Developments in Agronomy

Food, Energy and Values: Reflections on the Global Food Issue

Walter Leimgruber*

Department of Geosciences, University of Fribourg, Switzerland

*Corresponding author: Walter Leimgruber, Department of Geosciences, University of Fribourg, Geography Unit, University of Fribourg/CH, Switzerland

Submission: August 18, 2017; Published: December 07, 2017

ISSN: 2637-7659 Volume1 Issue1

Abstract

The problem of food supply has been the object of discussions since Malthus. Usually, the roots of and the solutions to this problem are exclusively sought in environmental and technical fields: harvest failures, inadequate food distribution, food prices etc. in other words, quantitative arguments dominate the debate. While these factors doubtlessly play an important role, they are not the only reasons for the fact that about one billion people on our Planet suffer from hunger and/or malnutrition. This paper reflects on the superficial and on the deeper reasons for the food problem. It argues that we are confronted with a complex situation that is linked to the close relationship between environmental and societal problems. Agriculture (the food provider) is not only dependent on physical conditions (soil, water, weather etc.) but is anchored in cultural practices, both on the producer and the consumer side. Besides, the lust for power and the greed for material profit along the entire food chain have transformed this field into a political and neoliberal playground with dire consequences for the underprivileged and the poor. The answer to the global food crisis lies therefore not only with technological solutions but in human attitudes towards food and nutrition.

Keywords: World hunger; Food; Nutrition; Energy; Value systems

Introduction

The importance of food and nutrition

Eating and drinking are the most basic needs of every living being, they are part of what [1] calls subsistence needs (which include, among others, also health, shelter, work and others). It is therefore understandable that food and nutrition have become increasingly central issues in our time, given the rising world population and the shrinking land surfaces available for food production, to say nothing of the increasing consumption of unhealthy food. In countries of the 'North', food has increasingly been marginalized in people's minds, as can be seen from the small percentage it occupies in their budgets. If in the early forties, people spent up to 30-40% of their income on food, this Figure lays nowadays around 10% or even less. Food, like everything else, is connected to ideas, values, perceptions, whatever social phenomena we study, we also have to consider their immaterial side. The global food issue is thus related to the way nutrition (a qualitative notion) has been marginalized for the benefit of food stuffs and the profits to be made out of them (the quantitative side). What is essential for survival (what we eat), has been replaced by the superficial idea of how much we devour.

Discussions on hunger and malnutrition mainly refer to countries of the 'South', particularly Africa, to some extent also parts of Asia and Latin America. Pictures of children dying from lack of food mark the headlines, symbolically accusing the 'North' of not doing enough to solve the problem. According to this perspective, this same 'North' has no hunger problem. The 'South', on the other hand, constitutes a vast marginal region when it comes to food and nutrition. While this statement is basically true, it is too general and requires a wider perspective. The food issue is in reality a global problem that has to be tackled from different sides. Hunger is only one aspect of it, and it is the one most frequently publicized. "Despite some improvements over the last several decades, far too large a portion of the world's population suffers from poor health brought on by hunger, malnutrition, poor diet and unsafe food and water"[2].

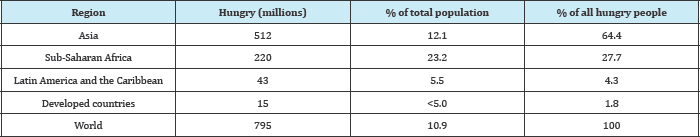

We are confronted not with a statistical issue but with a social one. Even in countries with a high percentage of undernourished people, the rich are usually well nourished , and in the seemingly rich 'North', there are persons at the lower end of the social ladder who do not always get enough to eat (Table 1). The situation of Africa is complex: since 1990-92, under nourishment in Sub- Saharan Africa has declined from 33.2% to 23.2% in 2014-16, although the number of hungry has gone up over the same period from 176 to 220 million [3].

We therefore face a problem of inequality: on the one hand millions across the Planet have not enough to eat, and their food is often of a low nutritional value, on the other hand, other millions have too much to eat and often consume the wrong food. While from a quantitative perspective, the 'North' may be well served, it is suffering from a quantitative and qualitative problem (consuming too much of the wrong food), as the increase of obesity [2], strokes and heart-related diseases show [4]. The food issue is not only a (quantitative and qualitative) lack of eatables but a skewed image of which food is essential nutrition-it is a matter of the mind as much as a matter of substance.

Table 1: Hungry (undernourished) people in the world, 2014-16.

Source: FAO 2015, p.8.

From a wider perspective, food furnishes the energy we need to live and work, but it has both a quantitative and a qualitative side. Quantitatively, the amount of food we have to consume in order to survive in a particular lifestyle (type of work, place of living) is determined by the Basic Metabolic Rate (BMR), the number of calories our body requires every day at complete rest. It amounts to about 25 kcal per kg body weight per day. In reality, because everybody is practising some physical activity, the figure lies much higher, varying from one individual to the other according to age, gender, activity level, size and weight. If we do not get enough energy, our body will no longer be able to function correctly, if we consume too much, it will store the excess calories in the tissue, and obesity will eventually result. The FAO has adopted a threshold level of 2,700 kcal per day "as an indicator of the level of satisfaction of food security requirements' [5]. Qualitatively, our diet has to comprise different substances which are essential for the functioning of our metabolism (proteins, carbohydrates, fats, vitamins, tracer elements, micronutrients). There should be a balance among them, because the over consumption of carbohydrates, for example, will also result in obesity.

The marginalization of food - and ways out

While we all have to eat and drink in order to survive, our attitude has changed. What was once considered an indispensable part of daily life and expenditure has become almost quantite negligeable in our minds. Particularly in the 'North' we take it for granted that the shelves in shops and supermarkets are always full with fresh produce, for which we are no longer ready to pay a fair price. Indeed, prices are under pressure: customers demand cheap food, which reduces farmers' incomes, but for them the usual prices for all consumer goods apply. Food and nutrition have been relegated to the margins of our thinking: they are deemed quantitatively essential, but the quality is still of little concern. The relations between health and nutrition are known in the scientific world [6] International Assessment, 2009, pp.17-20) but have still been poorly understood by many people.

In the light of the many problems facing humanity, it is essential to put food and nutrition back into the centre of our preoccupations: population growth and urbanization mean that more mouths have to be fed, and cities and infrastructure devour increasing areas of arable land. As a consequence, more food has to be produced on diminishing surfaces. Also, eating habits change as a consequence of urbanization (meat instead of vegetables, convenience and fast food instead of natural products). These problems have been building up in the 'South' with its accelerated population growth and rampant urbanization that not only reduces the amount of arable land for food production, but also results in changes in taste that force the producers to continuously adapt to new requirements. More urban dwellers equal more meat eaters (PECC 2003-04, p.8f.). "Urban residents in the Philippines, for example, eat twice as much "prestige foods" - meat, poultry, eggs, and dairy products -as do their rural counterparts who eat more rice, corn, roots and tubers, and vegetables." (ibid., p.9). However, meat production requires many vegetable calories that could be consumed directly by humans [3].

The food issue has two sides. On the one hand nutrition is largely marginalized in both politics and economy in the 'North', it is more important to produce ever increasing quantities of all kind of food than to concentrate on the qualitative aspect. Qualitative means food free from chemical. On the other hand, a large part of the world population is simply marginalized for the sake of 'northern' comfort and economic profit. What is the sense of growing cash crops in the 'South' for the 'northern' market if the local populations are starving because of a lack of land? Hunger concerns primarily rural populations [7]. They face multiple problems: lack of land or access, little information or knowledge how to use existing resources, ignorance of their legal possibilities etc., and they are often marginalized in the political discourse, as is the case of pastoralists in Kenya [8].

Food Production: Material Aspects

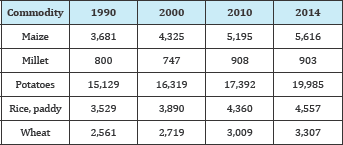

It has been said above: the food crisis is a complex phenomenon and has a large variety of material and spiritual roots [9]. While we prefer to look at the agricultural production statistics with their emphasis on the material side, we forget about the non-quantifiable immaterial side; the food issue has also an ethical aspect. Measures to tackle the food issue have therefore to be taken on several levels and by a variety of agents, and they will not meet with universal approval. On the purely technical side, a substantial increase in production is not urgent as there is enough food for the global population. Agricultural output has been steadily rising over the past 18 years [10], as the increase of the yields per hectare for selected years show (Table 2).

Table 2: Yields per hectare (in kg) of five essential crops, 1990-2010.

Source: FAOSTAT-Agriculture (http://www.fao.org/corp/ statistics/en/; 17.08.2017).

Bearing this in mind, [11] notes, "Today, the reason why nearly a billion people are undernourished is not that there is insufficient food to go round. If the world's food production were added up and then divided equally between the world's population, then each person would have 2,700 calories a day-an average easily sufficient to eradicate hunger." We have to bear in mind, however, that about one third of the cereal production is used for animal fodder [10]. Those calories are spoilt: animals need between 3 and 12 vegetal calories to produce one animal calorie.

While these statistics may give rise to hope, the quantitative increase does not solve the problem. According to the FAO, "achieving food security requires:

I. An abundance of food

II. Access to that food by everyone

III. Nutritional adequacy

IV. Food safety."

FAO 2001, emphasis in the original [2]. The first factor can be measured statistically, but the others are of a qualitative nature and difficult to assess. The figures given above are therefore only one part of the reality. To supply everybody on Earth with enough food of a good nutritional value to ensure good health is next to impossible under current conditions. We have to dig deeper and look behind what really drives the food and nutrition problem, turning to a less materialistic side of humans.

The Ethical Side of the Food Issue

Ethics and values

Human decisions and actions are guided by the dominating way of thinking or paradigm, which determines our attitudes. Up to the Industrial Revolution, humans were very much at the mercy of nature; they were subject to natural forces, largely helpless in the case of catastrophes, and used to adapt themselves to local circumstances. After the Enlightenment 'revolution' of the 17th century, Europeans began to dominate nature, seeing it as the bountiful and unlimited source of wealth (and the bottomless sink for waste), exclusively at the service of Man. The prevalent world-view changed from the ocentric to anthropocentric within a few hundred years [12]. Nowadays we are going through a painful learning process as we have to rethink our value system with respect to our attitude towards nature. "Man is still a 'fragile' biological being and will remain so for the foreseeable future" [13].

Figure 1: The value continuum (Source: Leimgruber 2004b, p.71).

Resource exploitation is based on economic reasoning and on the prevalent value system. Values are guiding principles and the basis of all our considerations, decisions, and actions, and every individual and every society has its own set of values. They are not static but evolve over time, oscillating on a continuum between the two extremes of 'secular' and 'sacred' [14], Figure 1. Cunha et al. [15] speaks of the existentialist and productivist paradigms, whereas Fernandes and [16] use the terms eco centrism and techno centrism. The latter authors arrive at the same conclusion as Cunha and the author by affirming that every evolution is cyclic and oscillates between extremes. Whatever terminology we use, it certainly questions the idea of an unlimited growth of the economy, consumption and production-growth and decline are normal phenomena. Dynamics occur following migration or information exchange through the various media of communication [14], and value change is responsible for social change [17]. Because our western civilization has privileged secular values over the past centuries, we must now increasingly include sacred values in our actions and strike a balance between the two. Depending exclusively on secular values (such as innovation, exploitation, arrogance etc.) will lead us as much into a dead end as concentrating solely on sacred values (such as conservation, sustainability, humility etc.).

Value shifts have been common throughout history, from early human societies totally dependent on nature to our industrial society seemingly free from it. The old Greek civilizations (in particularly Athens) deforested their territories, and so did the European civilizations of the middle. Ages and the Renaissance, and certain native tribes and civilizations in the Americas [18]. Inconsiderate ecological behaviour has been provoked by the perception that the resources (such as forests, but also fish) were available in seemingly unlimited quantities and could therefore be used at liberty-linear thinking dominated the human mind. We call such resources 'renewable', but we forget that renewal requires both time and an intact ecosystem. A look at the many societies in history that have collapsed and disappeared because of erroneous perceptions of the environment [19] illustrates the fact that humans are often unable to learn from the past and from others-something that continues into the 21st century.

However, since the 1970s we have been experiencing a gradual turnaround. The limits to growth have been demonstrated [20], and organic agriculture is on the way to become main stream. The organic food market has been growing substantially all over the world [21,22]. The benefits of vegetables grown without the application of synthetic fertilizers and the use of pesticides have been recognized. Opposition to genetically modified food has been growing steadily because of the unknown long-term risks to humans and the environment. Conventional methods of animal husbandry are questioned, and the impetuous use of antibiotics is posing problems to human health [23]. Attitudes are changing, and it is the consumer who has the power to induce this change. This is precisely what has been happening in the past few decades, parallel to the seemingly boundless increase of so-called conventionally grown food. It is a shift away from extreme secular to more sacred values, not a return to the Middle Ages, but a correction of the way humanity has been going [24], calls it a shift from a technologically minded A-society to an ecologically driven B-society. We have learnt that the Earth is an ecosystem, a living being, Gaia, as [25] called it and whatever humans do to it will eventually backfire-in the positive as well as in the negative sense [4].

The value shift and its consequences

A value shift is occurring with producers and consumers. Until now, nutritional experts discussed the food crisis from the health perspective, agronomist proposed new farming techniques, seed, fertilizer, and pesticide producers emphasized their key role in providing solutions, and politicians continued to make nice speeches and sign meaningless declarations. All these groups have been looking exclusively at the material (technical) side of the hunger and malnutrition issue, based on reductionist or linear thinking, but ignoring the complex relationships that exist in the global and in every regional ecosystem. The Indian ecologist Vandana Shiva calls this way of thinking 'monocultures of the mind' [26], thereby advocating not only biodiversity but also diversity of thinking.

Geographers have no problem in following Shiva's reasoning. They know the benefits of a holistic approach, that everything is connected to everything. This can be summed up in the notion of ecosystem: everything is connected to everything in a dynamic way, and the whole is more than the sum of its parts. System thinking is non-linear, and therefore more complex and more difficult. It is also a way of thinking that can lead us back from an overemphasis on secular values towards a balance between the two extremes. Complexity, however, is not limited to the relationships between the elements of a material system but also concerns our ways of thinking, e.g. when it comes to find solutions to a problem (such as the food crisis). There is a general tendency among politicians and economic leaders to evoke the TINA syndrome (There Is No Alternative) when it comes to push through specific interests. However, "alternatives do exist, but are often excluded.” [27]. The simple call for more production, genetically modified seeds, more pesticides and synthetic fertilizers falls short of the reality of a complex phenomenon.

Farmers are at the beginning of the food chain, and they always operate under circumstances of uncertainty, in particular as concerns weather conditions. The answer to such uncertainty is flexibility, the "adaptability to changing conditions of production, whatever those changes may turn out to be” [28]. Short-term flexibility will have to be completed by a long-term strategic outlook when it comes to live with the consequences of global warming (ibid.). Farmers are among those producers who have to look for alternatives all the time. These include sustainable agricultural practices that may reach from minor changes (reduction of synthetic inputs) to extremely radical transformations (organic or even biodynamic systems, [29]. Such a shift in the value system will gradually improve environmental conditions and influence certain segments of industry (for example, less or no synthetic input improves soil quality and entails a reduction in the production of these substances). While in the beginning of this century there was "little evidence at a global level that sustainable agriculture is being promoted widely.” (ibid., p.211), the market for organic products has been growing steadily. Consumer demands are a powerful force [3].

Following the shift towards extreme secular values, farmers have become industrial (mono cultural) nentrepreneurs, inevitably losing touch with the ecological reality. They became dependent on a limited range of products, the price policy of their wholesale customer (which often included fixed harvesting times), and the whims of the market. However, droughts or thunderstorms can reduce their harvest to nought, a disease may wipe out their livestock-uncertainty is much greater than when they cultivate multiple crops with different harvesting times, which can buffer extreme events. The input of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides and their indiscriminate use (abuse) result in a rapid degradation of the soils and decreasing yields [30,31] and in the killing of animals that were not targeted but died of poisoning [32]. In the manner of the boomerang effect the consequences even touched human beings: the spraying of dieldrin "in Illinois wiped out robins, brown thrashers and meadow-larks, killed sheep in the pastures, and contaminated the forage so that cows gave milk containing poison” [3].

Food, nutrition, and the energy question

Food and nutrition are part of the energy cycle, a relationship that has been discussed since the 1970’s, [3,34-38]. On the one hand, they provide the consumers with the energy needed for survival (dietary energy), on the other hand they are the result of a considerable energy input during the production and transportation process [39]. Part of this input is direct (primary) solar energy, but a major part is secondary energy (electricity, fossil fuel).

The nutritional problem: dietary energy

As has been emphasized before the food problem is a quantitative and qualitative issue. It is true that global food production is sufficient to supply us with the minimum energy requirement, but energy (as measured in calories or joules) is only one of the ingredients of our nutrition. Vitamins, proteins, tracer elements, and drinking water are as much part of nutrition as rice, potatoes or bread. In order to eliminate malnutrition, a balanced diet, if possible of genuine (organic) products consumed at regular intervals is necessary to remain in good health. This includes physical, social, and psychic factors, qualitatively good and balanced nutrition, sufficient drinking water, physical exercise, a healthy environment, good social relations, self-consciousness, etc. In its Constitution, the World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as "a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of diseases or infirmity." The importance of health is such that it is immediately afterwards declared "one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition” [40].

The food issue is therefore intimately related to people's physical and psychic wellbeing. We can safely say that the attitude towards food is also the attitude towards one’s health (and ultimately towards life). This has been largely forgotten because access to food has been taken for granted in the 'North’. It is also mirrored in the percentage of people's income that is spent on food. Swiss citizens spent 35 per cent of their salaries on edibles in 1945, but only 7 per cent in 2009 [41]. Food had become so common that it was treated like any other commodity and increasingly ended up in the dustbin. For the author, born before World War II and having lived through years of rationing, this is a scandal. It is not only morally wrong, it is also a waste of energy.

The issue of food (and energy) waste

In periods of dearth food takes a significance that differs from periods of plenty. Nobody wasted food during World War II, but when the food situation improved along with the economic boom of the 1950s and 1960s, attitudes became more relaxed and food was treated as a common good like everything else. The morality had changed within a short period, although not everywhere and with everybody. The environment was seen as an inexhaustible source of food, and, in a similar line of thinking, as the bottom less sink for all our waste. A wakeup for the latter call was a report of the British government’s Waste and Resources Action Programme [42]. Researchers had sampled the dustbins of 2,138 private households (no restaurants or canteens) and discovered that people throw away food that would cost an average family £420 annually, a family with children even £610 (ibid.). Obviously, most people still have enough money to afford such waste.

What held good for Britain obviously also holds good for Switzerland, for example. Research published by the WWF showed that in 2012 about one third of all food produced for Swiss consumers was discarded somewhere along the food chain, with households accounting for roughly 45% of that waste. This means that "every person buys on average 1.5 kg of food per day (excluding non-edible components such as peels and bones) and throws away about one fifth. This is the equivalent of 320 grams per persons or almost one entire meal per day” [43]. This translates into considerable costs for families. "Every Swiss household discards food that costs between 500 and 1,000 Swiss Francs per year. The Swiss invest several billion Francs in food that will never end on the plate." (ibid., p.5). These figures do not take the environmental costs into account.

Everybody agrees that rotten or mouldy food must be discarded for health reasons, but food remains after a meal can usually (especially in private households) be re-used, i.e. warmed up or made into another dish. This is a sign of respect. When this is not possible, alternative uses can be cooking the remains up for pig feed, dump them onto a compost (eventually through a public service), or transport them to a biogas plant. This may be defendable as the energy contained will be returned into the cycle. Food leftovers that are simply thrown away with all other garbage, however, are food waste, a practice to be condemned. Since food production requires an energy input, and our diet provides us with energy, food waste is also a waste of energy. In the US, this has been calculated as the equivalent of about 300 million barrels of oil per year [44], i.e. roughly one barrel per person. In energy terms, the evolution over the last 30 years of the 20th century has been catastrophic. "In 1972 approximately 900 kcal per person per day was wasted whereas in 2003 Americans wasted ~1400 kcal per person per day or —150 trillion kcal per year. "(ibid.). This means "that food waste has progressively increased from about 30% of the available food supply in 1974 to almost 40% in recent years.” (ibid.). The figure of 1400 kcal is only little below the minimum daily caloric requirement of a man of 70 kg body weight. In other terms: with the food waste of two Americans, another person could survive! However, we have to assume a differentiated perspective. Food waste as studied includes peels, bones, stones and kernels, and other inedible parts of vegetable and fruits unavoidable food waste [45], substances that can be composted and are therefore not really waste (ibid., p.209)-they will return into the energy cycle. Depending on the type and size of household, unavoidable food waste ranges between 2.6 kg/week (140 kg/year) for families with children under 16, and 1.3 kg/week (70 kg/year) for single occupancy households (ibid., p.173)-average figures, of course. The weight translates into cost. Looking simply at average figures, every household spends about £590 on food that is being thrown away (all categories combined), £170 (29 %) of which are unavoidable (ibid., pp.23, 27).

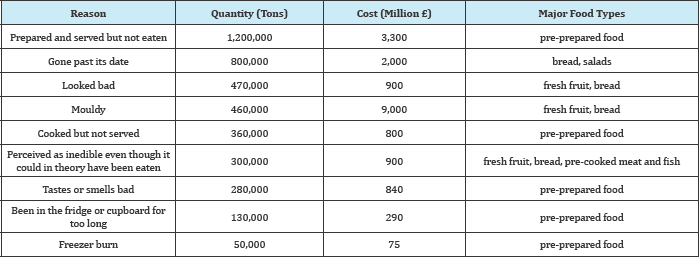

Why do people throw food away which would in fact be avoidable food waste (81% of all food waste belongs to this category)? The reasons are quite diverse (Table 3). Improper management of the food purchased leads the list before many others (ibid., pp.27, 168). Most of the waste is food left on the plate after a meal-the quantities were too big. Leftovers, however, can be eaten at home, a practice obviously followed less nowadays than in former times.

Table 3: Reasons for throwing away food that could have been eaten (avoidable food waste).

(Source: WRAP 2008, p.168).

The second most important reason is the date printed on the packages (sell by ..., consume by ...). Discarding food simply for this motive shows to what extent many people have dumped common sense. The reference dates printed on the packages are there to ensure that the shops do not sell old and decaying food. They do not mean that a product is bad and inedible on the day after. But most people have become addicted to the precision of a date and will throw entire packages away, without reflecting a second. A test by the alliance of Swiss consumer organizations has revealed that even perishables like milk, yoghurts, cooked ham, desserts etc. can be consumed up to four weeks beyond the date [45].

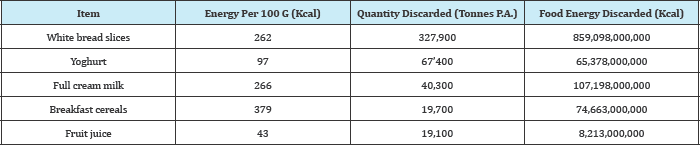

The third reason shows the impact of perception, food looks bad or is perceived as inedible. Again, most consumers choose the simple way, instead of trying to overcome this problem. Eventual bad parts can be removed (oranges or apples do not rot in their entirety at a single moment), dry bread can be soaked in milk and eaten like this or used to prepare another meal, to quote just two examples. Only where mould is involved, discarding is justified for health reasons. How much energy is being lost in this way? This question cannot be fully answered in the present context, but a small attempt will be made to illustrate it. A complete answer would have to include the energy used for the production, eventual processing, transportation, and for disposing of the waste-we might call this 'external energy', apart from the nutritional energy contained in the products themselves ('internal energy'), [44] have studied this question with reference to the US (see above), but their figures are not based on actual food waste counts. We want to be more modest and take a few of the British figures to calculate only the internal energy of the food waste registered. The Figures are approximations, not to be taken at face value, but they serve to demonstrate the waste of just one energy aspect of our diet. The energy input into the growing and production of this food remains a mystery, and so is the energy needed to do away with the waste.

Table 4: Food energy thrown away in household waste Based on WRAP 2008.

(The energy content was sampled during a voyage on a containership, January 2012).

The figures of Table 4 have to be read with care because in each category there are items with differing energy content (full fat milk vs. skimmed milk, dark bread vs. white bread etc.), but they are indicative of the many calories that are often thoughtlessly discarded. Many people could have been fed with this food, less food would have to be produced (and less 'external' energy used for production) if only a part of this waste had been consumed. The clue to the solution of the global food crisis also lies with 'northern' attitudes to food. It is still taken for granted that we always have enough to eat, that famines are something of the past. We have adopted a one-way (or throw-away) mentality, characteristic for "shopping as a social practice" [46], which is the result of a value shift towards the secular extreme of the value continuum. This resulted in a surplus society that became totally estranged from nature [47] and in the creation of large quantities of waste. Mono- cultural farming geared towards profit has replaced traditional farming methods that tried at least to be in harmony with nature [48].

Conclusion

Many questions remain open in the end, and new ones arise. Is the global food crisis just a crisis in our minds, i.e. does it exist in our imagination only? Is it only a natural and inevitable consequence of population growth? Or is mine simply a crazy interpretation of a phenomenon that is largely independent of Man and is related exclusively to natural causes (such as climate)? Indeed, this issue is "not only economic, social and political in nature, it is also an ethical and spiritual crisis that can only be overcome through different ways of thinking, new strategies for action, and changed patterns of living" [49]. To solve this scourge is therefore first and foremost a social task and requires a radical change of attitude. Such changes have occurred throughout time and will continue to happen. While the productivist paradigm in agriculture is gradually giving way to a new (post-productivist) outlook [48], more action is needed, especially in the field of consumer behaviour.

The most important step is to replace the current materialist and technocratic view by a holistic approach. Many policy recommendations still concentrate on food prices, climate, water, competition for land, etc. [11,50,51] although other programmes have put the focus on an improved interaction between humans and nature [52]. Such programmes are directed towards rural populations and their natural environment; however, it is the urban population that should learn more about such interactions. People in cities have become alienated from nature and the countryside, and they should understand where our food comes from. Women can play an important role in such a learning process, in particular in cities of the 'North' [53].

It is also a challenge for agriculture, the root for our food supply, and which bears a high responsibility for human health. It has for many decades been under the influence of the 'secular' values of profitability and efficiency, but in recent years farmers have begun to feel the negative impacts [30,31]. The current value shift towards the 'sacred' side includes acknowledging that traditional farmers have a good knowledge of their agro-ecosystem and of the plant varieties suitable for nutrition [54,55,56], and re-appreciating subsistence farming, which is uneconomic by capitalist standards, but economic from the ecological perspective. Traditional must not be confused with old-fashioned, as has been done in the euphoria of progress and technological advancement. It would be wise to trust the holistic knowledge of farmers and promote their activities rather than privileging industrial practices that ultimately destroy the very basis of farming, the soil. The experience by farmers in northern Malawi demonstrates that such a holistic approach, coupled with local expertise, helps to enhance food production and to promote social change [57].

The food issue is above all a moral issue and related to our attitudes towards farmers and food. Farmers, and with them rural communities, have often been considered marginal groups because they participate less in the so-called progress of the industrial world [58-69]. As a consequence, an attitude of condescendence has developed. While they continued to provide us with the food we need, some of them became victims of the productivist philosophy, producing for a market that was dictated by the food industry, life-style trends, and by consumer demands for more and cheaper products. In this context, food has become little more than a commodity that was bought and consumed (and discarded) just like any other consumer object (e.g. tooth brushes). Its value as nutrition has been marginalized because quantity was considered more important than quality.

References

- Max-Neef M (1982) From the outside looking in: experiences in barefoot economics, Uppsala, Dag Hammarskj Old Foundation

- FAO (2001) Ethical issues in food and agriculture. Rome: FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization), Italy.

- FAO (2015) The state of food insecurity in the world. Rome: FAO (Food and Agricultural Organisation), Italy

- Lovelock J (2006) The revenge of Gaia. Why the Earth is fighting back - and how we can still save Humanity. London: Allan Lane/Penguin Books, UK.

- FAO (2003), Agriculture, food and water, A contribution to the World Water Development Report. Rome: FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization), Italy

- Hels O, Hassan N, Tetens I, Haraksingh TS (2003) Food consumption, energy and nutrient intake and nutritional status in rural Bangladesh: changes from 1981-1982 to 1995-96. Eur J Clin Nutr 57(4): 586-594.

- SDC (2007) Securing enough food for all, Swiss Development Corporation. Bern, Switzerland.

- Wako F (2007) The politics of marginalization: the case of the pastoralist communities in Kenya. Paper presented at the World Social Forum in Nairobi, 20 - 24th January

- Leimgruber W (2011) Organic farming-a promising future for humanity. The Malaysian Journal of Tropical Geography 35,1+2 (year 2004), pp.1- 15

- FAO (2009) The state of food and agriculture. Rome: FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization)

- Evans A (2009) The feeding of the nine billion. Global food security for the 21st century. A Chatham House report, London: The Royal Institute of International Affairs

- Leimgruber W (2004a) Values, migration, and environment. An essay on driving forces behind human decisions and their consequences, in Environmental change: implications for human migrations, Dordrecht: Kluwers 20: 247-266.

- Gustafsson G (1992) Future lifemodes and regional development: life philosophies, spatial organizations and the use of natural resources, in Gade O. (Ed.), Spatial dynamics of highland and high latitude environments, Occasional Papers in Geography and Planning 4: 89-97, Department of Geography and Planning, Appalachian State University, Boone (North Carolina).

- Leimgruber W (2004b) Between global and local. Marginality and marginal regions in the context of globalization and deregulation. Aldershot: Ashgate

- Cunha A (1988) Systemes et territoire: valeurs, concepts et indicateurs pour un autre developpement. in: L'Espace Geographique 3: 181-198

- Fernandes JLJ, Carvalho P (2001) Conservation, development and the environment: a conflictual relationship or a different view for new geographies? in Jones G, Leimgruber W & Nel E (Eds. 2007), Issues in Geographical Marginality. Development and Environment, CD-Rom, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, 46-54.

- Welzel C, Inglehart R (2010) Agency, values, and well-being: a human development model. Soc Indic Res 97(1): 43-63.

- Krech III S (1999) The ecological Indian. Myth and history, New York/ London: W.W. Norton, Newyork.

- Diamond J (2005) Collapse. How societies choose to fail or survive. London: Allen Lane

- Meadows D, Zahn E, Milling P (1972) The limits to growth, Universe Books, New York, USA.

- Hope A (2012) Bio on the increase. More organic farmland needed as one in five people buys bio products regularly, Flanders Today 27.04.2012.

- Kreuzer K (2012b) Organic sector in Switzerland continues to grow, Oneco News 18.04.2012

- Schiffman R (2012) Scientists cry fowl over the FDA's regulatory failure, The Guardian.

- Gustafsson G (2012) Ostmark, Marginalized in a Globalized World - Some Future Possibilities, Papers presented during the 32nd IGC, Cologne

- Lovelock J (1988) The age of Gaia. A biography of our living Earth, New York/London: WW Norton

- Shiva V (1993) Monocultures of the mind. Perspectives on biodiversity and biotechnol-ogy, London and New York: Zed Books, Penang: Third World Network, USA.

- Shiva V (1996) The war against species, in Miller G.T., Living in the environment. Prin-ciples, connections, and solutions, (9th edn.), pp. 298299, Belmomnt CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company

- Aase TH, Chaudhary RP, and Vetaas OR (2009) Farming flexibility and food security under climatic uncertainty: Manang, Nepal Himalaya. Area 42(2): 228-238.

- Bowler I (2002) Developing sustainable agriculture, Geography 87(3): 205-212.

- Aubert C (1996) Chinese agriculture, the limits of growth, Itineraires No. 46, Graduate Institute of Development Studies, Geneva 3-34

- Tilman D (1998) The greening of the green revolution, Nature 396, p. 211 f.

- Carson R (2000) Silent spring, London: Penguin (originally published in 1962)

- Carson R (1998) A new chapter to Silent Spring, in Lear L (ed.), Lost Woods. The discov-ered writings of Rachel Carson, Boston: Beacon Press, pp.211-222

- Hirst E (1974) Food-related energy requirements. Science 184(4133): 134-138.

- Chancellor WJ, Goss JR (1976) Balancing energy and food production, 1975-2000. SciTech Connect 192(4236): 213-218.

- Leach G (1975) Energy and food production, Food Policy 1(1): 62-73.

- Nonhebel S (2005) Renewable energy and food supply: will there be enough land? Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 9(2): 191-201.

- Tilman D, Socolow R, Foley JA, Hill J, Larson E, Lynd et al. (2009) Beneficial biofuels-the food, energy, and environment trilemma. Science 325(5938): 270-271.

- Pirog R, Benjamin A (2003) Checking the food odometer: Comparing food miles for local versus conventional produce sales to Iowa institutions, Leopold Centre for Sustainable Agriculture, Iowa State University, Ames

- WHO, 1946, Constitution of the World Health Organization, New York: United Nations

- Swiss Statistics (2011) Household budget Survey 2009, Press Release 15.11.2011, Neuchatel, Swiss Federal Statistical Office.

- WRAP, 2008, The food we waste, Banbury: Waste and Resources Action Programme, http://www.wrap.org.uk/retail/case_studies_research/ report_the_food_we.html (accessed 20.07.2010)

- WWF Schweiz & foodwaste.ch, n.d. [2012], Lebensmittelverluste in der Schweiz - Ausmass und Handlungsspielraum, http://foodwaste.ch/wp- content/uploads/2012/10/12_10_04_WWF-foodwaste-ch_final1.pdf (12.10.2012

- Hall KD, Guo J, Dore M,CC Chow (2009) The Progressive Increase of Food Waste in America and Its Environmental Impact. PLoS ONE 4(11): e7940.

- Stiftung fur Konsumentenschutz (2012) Lebensmittel uber dem Ablaufdatum: haufig noch gut, Medienmitteilung 03.05.2012 (available online at http://konsumentenschutz.ch/medienmitteilungen/ archive/2012/05/03/lebensmittel-ueber-dem-ablaufdatum-haeufig- noch-gut.html; accessed 07.05.2012)

- Everts J, Jackson P (2009) Modernisation and the practice of contemporary food shopping, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 27: 917-935.

- Maude B (1975) The turning tide. Towards the post-surplus society, London: Faber & Faber

- Leimgruber W (2001) In Harmony with Nature - the importance of the productivist cycle for rural areas. in: Pelc S. (ed.): Developmental problems in marginal rural areas: local initiative versus national and international regulation. Proceedings of the Marginal Areas Research Initiative Meeting. Ljubljana/Preddvor, 25-29 June 2000, pp. 15-26. Ljubljana: Faculty of Education

- Mann P, Lawrence K (1999) Rebuilding our food system: the ethical and spiritual challenge, in: UNEP, ed., Cultural and spiritual values of biodiversity, Nairobi: United Nations Environmental Programme, pp.321-323.

- Fan S, Rosegrant MW (2008) Investing in agriculture to overcome the World food crisis and reduce poverty and hunger, IFPRI Policy Brief 3, Washington DC: International Food Policy Research Institute

- Von Braun J, Meinzen DR (2009) "Land grabbing" by foreign investors in developing countries: risks and opportunities, IFPRI Policy Brief 13, Washington DC: International Food Policy Research Institute

- Spielman DJ, Pandya LR (2009) Highlights from millions fed. Proven successes in agricultural development, Washington DC: International Food Policy Research Institute IFPRI

- Buckingham S (2005) Women (re)construct the plot: the regen(d) eration of urban food growing, Area 73(2): 171-179

- Plenderleith K (1999) The role of traditional farmers in creating and conserving agro biodiversity. In: UNEP, edn, Cultural and spiritual values of biodiversity, Nairobi: United Nations Environmental Programme, pp.27-291.

- Brokenshaw D (1999) What African farmers know, in: UNEP, (Ed.), Cultural and spiritual values of biodiversity, Nairobi: United Nations Environmental Programme 309-312

- Kabuye C (1999) The cultural values of some traditional food plants in Africa, In: UNEP, edn., Cultural and spiritual values of biodiversity Nairobi: United Nations Environmental Programme 312-315.

- Msachi R, Dakishoni L, Bezner Kerr R (2009) Soils, food and healthy communities: working towards food sovereignty in Malawi. Journal of Peasant Studies 36(3): 700-706.

- Everts J, Jackson P (2009) Modernisation and the practice of contemporary food shopping, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space vol. 27: 917-935

- FAO (2011b) The state of food and agriculture, 2010-11, Rome: FAO

- International Assessment (2009) International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development (IAASTD), Global Summary for Decision Makers, Washington, Island Press (online availble under www.agassessment.org, accessed 27.04.2012)

- Kreuzer K (2012a) Tanzania: wave of conversions in Kilimandjaro area, Oneco News 12.04.2012 (http://oneco. biofach.de/en/news/?focus = 9c8e9e14-ab6f-4d59-ad80- dd0edeb13e9c&fromnewsletter=true; accessed 27.04.2012)

- Nellemann C, MacDevette M, Manders T, Eickhout B, Svihus B, et al. (eds. 2009) The environmental food crisis-The environment's role in averting future food crises, UNEP

- PECC (2003-04) Where demographics will take the food system. Pacific food system outlook 2003-2004, Pacific Economic Cooperation Council, Singapore

- Spiegel online (2017) LebensmittelskandalMindestens 28 Millionen Fipronil-Eier nach Deutschland geliefert, 16.08.2017 (http://www. spiegel.de/wirtschaft/service/fipronil-mindestens-28-millionen- belastete-eier-nach-deutschland-geliefert-a-163044.html; accessed 17.08.2017)

- In Sub-Saharian Africa, about 15.3% of the children in the richest households are qualified as underweight, as against 28.8% in the poorest (defined by wealth quintiles; FAO 2011b, p.125, Table A6)

- Overweight among adults (15 years and more) In Switzerland, for example, has increased from 30.3% in 1992 to 41.1% in 2012 (https:// www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/themes-transversaux/ monitoring-programme-legislature/tous-les-indicateurs/ligne- directrice-3-securite/surcharge-ponderale.html9)

- To obtain one pound of beef requires about 16 pounds of soybeans and grains, producing animal proteins uses about 15 times the amount of water it takes for plant proteins (http://www.alternate-energy-sources. com/vegetarian-nutrition.html; accessed 25.01.2010). Almost half the global cereal production is used for animal feed (Nellemann et al. 2009, p.17).

- The global market for organic food and beverages is an estimated 54.9 billion US$ (c. 40 billion Euros) in 2009. More than 1.8 million producers operate on 37.2 million hectares (http://www.organic-world.net/ yearbook-2011-presentations.html?&L=0; accessed 07.05.2012).

- The recent egg scandal (eggs contaminated with an insecticide) in Western Europe demonstrates that not everybody has learnt from past experiences (Spiegel online 2017).

© 2017 Walter Leimgruber. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)