- Submissions

Full Text

Intervention in Obesity & Diabetes

Managing of Obesity and Diabetes of Elderly Inmates: Efficacy of Policy-Oriented Approaches

Heath D Harllee1* and Will Senn2

1University of North Georgia, USA

2Tarleton State University, USA

*Corresponding author:Heath Harllee, University of North Georgia, USA

Submission:February 08, 2025;Published: March 05, 2025

ISSN 2578-0263Volume6 Issue5

Abstract

The elderly inmate population has seen an exponential rise in population and is creating new and demanding challenges for the criminal justice system globally. Moreover, judicial policies for long-term incarceration have resulted in increasingly higher proportions of seniors living behind bars. The rise in elderly serving in the correctional system has been associated with a spike in obesity and diabetes prevalence among the prison population. Evidence shows that with proper dietary management, physical exercise, and stress management, the burdens of obesity and diabetes can be reduced in any population. However, it is unclear from the literature of research evidence how this would generalize to serving the elderly predisposed to obesity and diabetes from the aging process. Individuals incarcerated within penal systems globally appear to show an increase in obesity and diabetes consistently, and well-targeted judicial policies may be a solution. This study will examine the evidence for current judicial policies aimed at addressing obesity in prison populations, especially among the elderly serving.

Keywords:Elderly; Inmates; Obesity; Diabetes; Policy

Introduction

The elderly inmate population has seen an exponential rise in population and is creating new and demanding challenges for the criminal justice system globally. Moreover, judicial policies for long-term incarceration have resulted in increasingly higher proportions of seniors living behind bars. The rise in elderly serving in the correctional system has been associated with a spike in obesity and diabetes prevalence among the prison population. Evidence shows that with proper dietary management, physical exercise, and stress management, the burdens of obesity and diabetes can be reduced in any population. However, it is unclear from the literature of research evidence how this would generalize to serving elderly predisposed to obesity and diabetes from the aging process. Individuals incarcerated within penal systems globally appear to show an increase in obesity and diabetes consistently, and well-targeted judicial policies may be a solution. This study will examine the evidence for current judicial policies aimed to address obesity in prison populations, especially among the elderly.

The graying of the prison population poses unique challenges to the penal system as older prisoners present various custodial, healthcare, and social needs compared to their younger counterparts under the age of 50. To illustrate, a 50-year-old prisoner tends to represent the health burden of someone who is 10-15 years older in the community. In view of the fact that healthcare needs from degenerative and chronic conditions such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes are prevalent in inmates over the age of 50. In the United States, the population of inmates over the age of 50 has grown more than 400% since 1993 due to judicial policies for long-term incarceration rather than alternative custodial services. The prevalence of diabetes and obesity, along with its related comorbidities and complications, is projected to increase if current judicial policies continue [1]. For instance, the stringent judicial policy creating mandatory sentences, three-strike laws, and the so-called war on drugs have resulted in longer sentences [2]. Furthermore, the judicial policies in question come with an increase in the graying of prison populations, which carry a high risk for non-communicable diseases such as obesity and diabetes.

The proportion of U.S. adults who are overweight or obese now accounts for at least two-thirds of the adult population [3]. The mean body weight in the United States has gradually increased annually, and obesity continues to be among the top health concerns across the globe. Binswanger’s data suggest that among prison populations, obesity rates at the entry point of incarceration matched similar rates of those not incarcerated (Figure 1). Two of the most important risk factors for obesity are an individual’s diet and physical activity [4]. Incarcerated males in the United States have a 1.02 prevalence ratio of being overweight or obese compared with the general population [5]. Furthermore, nearly 80,000 of these inmates nationwide have diabetes, a prevalence of 4.8%, and at the point of intake, 29.8% of inmates nationwide are considered overweight or obese, requiring active management by correction services [6]. A deficiency of insulin characterizes type 1 diabetes due to destructive lesions of pancreatic B-cells. It typically occurs in young subjects, but it may occur at any age [7]. In contrast, Type 2 diabetes is caused by a combination of decreased insulin secretion and decreased insulin sensitivity. Type 2 diabetes, affecting over 90% of adults with diabetes, typically develops after middle age. The patients are often obese and physically inactive [8]. Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys indicate that people with diabetes have about two to three times the prevalence of inability to walk 400 meters, do housework, prepare meals, and manage money. With this taken into consideration, as well as the environment of prison, a heightened risk for obesity and diabetes has become a challenge within the penal system [9]. Without proper study of judicial policies and the potential effects on elderly inmates, we may not know how to address these largely avoidable non-communicable health conditions such as obesity and diabetes.

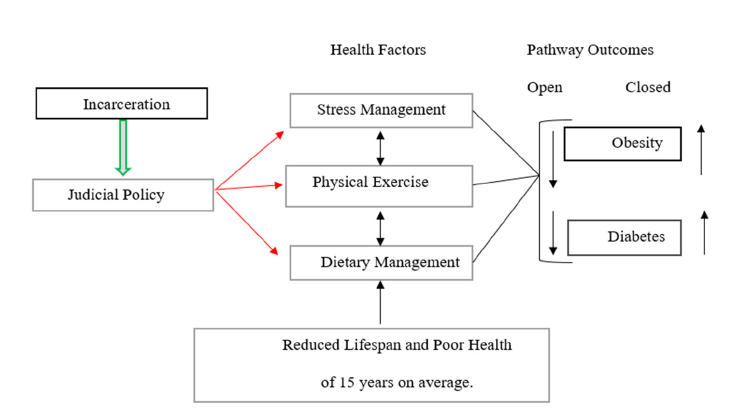

Figure 1:Obesity risk chain.

Judicial Policy Defined

Judicial policy refers to the process whereby judges “exercise power on the basis of their judgment that their decisions will produce socially desirable results” [10]. According to Feeley, this process occurs in two steps, with courts first invoking a legally authoritative text to establish their jurisdiction over an issue and then deriving the policy response to that issue from legally nonauthoritative sources. Judicial policies for health management vary by the nature and chronicity of disease acquired prior to and within the penal systems [11]. Judicial policy has played a critical role in the control of chronic diseases and the behaviors that lead to them; this is true for some health conditions rather than others [12]. Research suggests that judicial policy tends to focus on punishment and control more so than health and empathy [13].

Furthermore, judicial policy in 35 of the 50 states requires inmates to pay a medical copayment, which is applied to the prison budget [14]. This payment for services can be an obstacle as inmates have what may be other perceived needs than healthcare, such as alternative food sources and toiletries. Moreover, incarceration may also be a life event carried out in an intense and short period of time, thus affecting health in a manner consistent with the life events framework. Regardless, a majority of the illnesses being treated are related to metabolic conditions, and corrections systems’ judicial policies may be designed to address acute health conditions like heart disease and kidney disease rather than other chronic but less acute conditions like obesity and diabetes [15]. Preventive judicial policies may address metabolic conditions among prison populations in a multi-pronged way: physical exercise, dietary and glucose regimens, and stress management [16]. The use of judicial policy, legislation, regulation, and policy to address the multiple factors that contribute to obesogenic environments assists in the development and evaluation of a variety of policy approaches for obesity prevention and control within the correctional systems [17]. Three judicial policy instruments for health management with prison populations include physical exercise [18], dietary regiment [19], and stress management [20]. The aim of this review is to research the evidence on influences of judicial policies on the effective management of obesity and diabetes among the elderly population within the prison systems.

Physical Exercise for Obesity and Diabetes

Studies that have examined physical exercise for obesity and disabilities control have reported mixed findings. For instance, Edwards L [21] reported judicial policy restricted inmates from receiving proper exercise, which in turn creates obesity. Edwards also reported that historically, prison managers have felt that overweight, inactive inmates pose less of a security risk for corrections staff. Douglas and colleagues examined English women’s perceptions of the impact of incarceration on their physical health [22]. Women described few opportunities to be physically active within the prison, noting that existing exercise facilities were inadequate and that opportunities to use the prison’s gym conflicted with work schedules [22]. Physical activity within prisons is dictated by the prison regime, which controls what activity a prisoner can participate in and for how long. Moreover, the prison regime, and so the extent of potential physical activity, can vary in different prisons, typically depending on the security status of a prison and individual prisoner [23]. For instance, while gym equipment and recreational opportunities in prison used to be more extensive, a series of amendments (including U.S. Zimmer’s 1996 “No Frills Prison Act”) have limited the provision of and access to fitness equipment and/or instruction in federal prisons [24]. These restrictions have created a more sedentary environment, which in turn creates the ability to burn fewer calories and gain more weight. Several studies indicate that a substantial proportion of prisoners in the United States spend most of their time sedentary (locked down) and spend only a very limited amount of time out in the open air [25]. More study is needed to determine how physical exercise judicial policies have evidence for reducing the prevalence of obesity and diabetes among the elderly serving.

Dietary Judicial Policies and Obesity Control Among Inmates

Studies that have examined dietary polices for obesity and diabetes control have reported mixed findings. For example, Travis J [26] observed that “the nutritional value of prison meals in the United States is far from ideal because energy-dense (high-fat, high-calorie) foods are common” [26]. Moreover, the repetition of dishes also prevails, and reliance on processed and packaged foods is common [27]. Studies have also shown that the limited food choices provided in the prison were viewed as an important factor influencing unhealthy food choice, and the higher cost of healthy food in the prisons are felt to be driving prisoners toward cheaper, unhealthy food [23]. Despite the provision and storage of food that complies with prison general food-safety regulations and centrally pre-defined monthly menus, the final preparation and distribution of food are prisoners’ tasks. In this sense, the regulation of the distribution of a standard portion size is not established [28]. Thus, allowing for an accurate caloric count and nutritional value tracking is too inaccurate to maintain not allowing the inmate control over possible dietary restrictions and intake.

Given that inmates experience a higher prevalence of several chronic diet-related health conditions, such as obesity, compared to the general population [29], ensuring proper nutrition through a change of judicial policy for inmates might be beneficial to alter this trend. For example, caloric intake in corrections seldom includes fresh fruits, vegetables, or low fat and low sodium options; security concerns regarding offender and staff safety necessitate restricting and controlling of movement and diet [5]. In a 2013 study by the Healthy Food Access Project (HFAP), conducted with female inmates in Oregon, a diet and caloric intake change was made. The HFAP altered the food environment in the minimumsecurity facility primarily by implementing a reduced calorie menu that labeled the caloric content and incorporated garden produce into the meals [30]. The results were a 7% decrease in the number of inmates with reported Type 2 Diabetes and mixed results concerning BMI. Moreover, a study conducted by Binswanger et al. [29] found similar results as did Edwards study [21]. The question remains: Would inmates throughout all penal systems show similar results with this change in caloric intake?

Stress Management Judicial Policy and Obesity/ Diabetes Control

In the disease context, chronic stress could result in illness and disease as follows: stressor meaning stress imbalance susceptibility disease. In practice, however, early research efforts were largely confined to studying only the stressor disease relationship [31]. This might apply to how obesity and diabetes may occur in prison populations from the stress of incarceration. Massoglia & colleagues [32] reported on stress management in the prisons and found that the incarceration experience may differentially expose individuals to stressors over the life course. With incarceration, stress risk is heightened from needed behavioral adjustments in a relatively short period of time. Stressors and major life events have been linked to numerous negative health outcomes, such as obesity and diabetes [33]. Studies have shown that severe or chronic stress can weaken the body’s ability to respond to additional stressors and manage health [34] through a process known as the allostatic load.

The allostatic load can be defined as “the cumulative toll on the body from elevated use of physiologic systems” [35]. Empirical studies have demonstrated that allostatic load is patterned on incarceration experience [36]. In a 2014 study [23] conducted by nurses in the prisons of the United Kingdom, findings were that imprisonment was felt to affect the weight of prisoners due to stressors indirectly. Factors such as the stress from being away from family and friends and the realization that they were in prison caused overeating, resulting in weight gain. Studies are needed on judicial policies for stress management among prison populations to manage the risk for obesity and diabetes [37].

Theoretical Framing of the Study

A path dependency syndrome may explain judicial policy influences on obesity and diabetes control. In law, path dependency occurs when the “ideational constraints of liberal legal doctrine” [38] restrict the content of judicial decisions, which in turn “block one path of development while encouraging another” [39]. Three measures of United States social health that have attracted increasing attention in recent years are the incarceration rate, the obesity rate, and the prices of our homes. As regards elderly inmates at risk for diabetes, the question is how judicial policy might promote the health of elderly inmates regarding what it allows or disallows. Judicial policies occur in two steps, with courts first invoking a legally authoritative text to establish their jurisdiction over an issue and then deriving the policy response to that issue from legally nonauthoritative sources [10]. Figure 2 represents the direct correlation that judicial policy could have on an individual after incarceration.

Figure 2 shows the direct impact that judicial policy can have on an individual once incarcerated. Judicial policy can lead to a caveat of symptoms and issues leading to chronic disease and illness, such as obesity and diabetes. Figure 2 also shows a direct correlation between stress management, physical exercise, and dietary management to obesity and diabetes. Furthermore, Figure 2 shows that when certain pathways are closed within the penal system, obesity and diabetes rates have the tendency to go up, which, in turn, with the other health factors, or lack thereof, cause a reduced lifespan of 15 years for the average inmate [40].

Figure 2:A direct link via three modes of effect that cause long-term repercussions.

Significance of the Study

The literature on older inmates’ health is fragmented and insufficiently developed. A review of how current judicial policy affects the elderly inmate population is needed, as well as a theoretical review of models that can aid the change of judicial policy. Opportunities exist for impact studies focusing on a broader spectrum of judicial policies as well as for continued judicial policy actions at every level of incarceration. The extent to which current judicial policy on all levels of incarceration addresses the obesity or the diabetic among serving is less well understood. In the current context of an exploding prison population, there is urgent need for evidence on judicial policies for addressing obesity and diabetes among prison populations, and especially elderly serving.

Research Questions

The study will aim to address the following questions:

Physical exercise for obesity and diabetes

1. How does physical activity and dietary policies relate to obesity prevalence among elderly inmates?

Stress management judicial policy and obesity/diabetes control

2. How does stress management judicial policy influence the morbidity rate among elderly inmates?

Judicial policy

3. How does judicial policy effect the diabetes rate amongst elderly inmates?

Methods

Research design

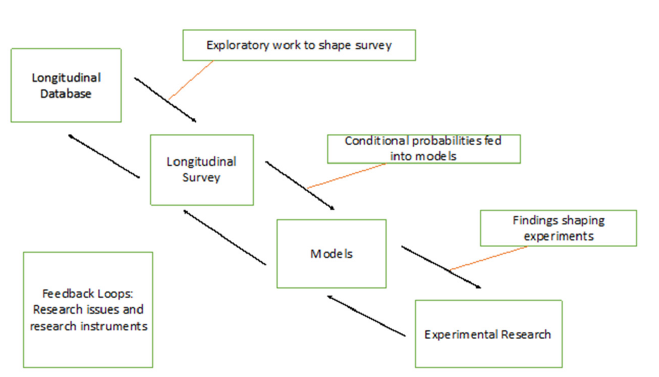

The research design will utilize a qualitative [41] approach to investigate how judicial policy affects the rate of obesity and diabetes amongst elderly inmates. The primary research method for this study is literature review and conceptual modeling. To answer the research questions before mentioned, this is the method of choice. An Accelerated longitudinal design will be used to gather data to answer the research questions and find additional gaps in literature and future research. In the accelerated longitudinal design, multiple panels are recruited and followed over a specified time interval. These panels have the quality of being uniformly staggered on key developmental stages [42]. Data such as BMI, diabetes negative or positive, previous incarceration, and age at entry point will be taken. This same information will be accounted for every 6 months up to the 5-year mark to measure changes in the elderly inmates throughout a given time period. Figure 3 shows research loops with experimental research using the longitudinal model.

Figure 3:Research loops with experimental research using the longitudinal model.

Sampling frame

The individuals chosen for this study will be subjected to similar measurements. All participants in the study will be: 1) 50 years-ofage or over the age of 50 either at the time of incarceration 2) or were incarcerated at an early date turned 50 inside the correctional system 3) All study subjects in the study are incarcerated in county or state prison and are at least the age of 50. 4) Comparisons made to younger cohorts refer to inmates under the age of 50 in similar incarceration units. 5)Comparisons made to their counterparts in the general public refer to individuals at least the age of 50 that have not been incarcerated.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Participants

The participants of the study to be chosen are individuals incarcerated in county and state prisons of the United States. Elderly inmates in this context will be assumed to be at least 50 years of age or older. An undetermined number of participants are subject to the study at this time, as future research will limit the number of participants to a manageable and accurate sampling. The participant selection for this study has been pulled from various archived data sets with the most recent dates available. Furthermore, the dependent variable concerning the participants will be obesity and diabetes as the independent variables of the study will be dietary management, physical exercise, and stress management. Participants included will be 50-years of age or older, incarcerated in a county or state facility, and suffering from either obesity or type two diabetes.

Exclusions

Individuals to be exclude will be those serving less than one year of incarceration and those who do not meet prior criteria.

Instruments

A questionnaire provided to the participants of the study will be an approved document of the University of North Georgia Research Integrity & Compliance Board. The questionnaire will require the socio-economic and demographic background of the inmate. Furthermore, questions asked will have to do with the inmate’s perception of nutritional and caloric intake as well as opportunities for physical exercise. Moreover, information concerning BMI during intake, current, and length of incarceration will also be examined. Positive or negative results for diabetes at intake, current status, and length of incarceration will need to be obtained. Information obtained through the Bureau of Statistics and the Department of Justice will be obtained as well to compare with the questionnaire results.

At no time will any financial incentive or false hope be given to the participants of release or early release at any time. The participants will be strictly volunteer and negative or positive consequences will not be garnered toward any inmate choosing to or declining to participate. All data obtained will be processed in an unbiased and scientific manner and collected by PhD candidates within the Health Services Research cohort at the University of North Texas. The primary investigator will be Heath Harllee, PhD assistant professor at the University North Georgia, Health Administration and Informatics department. The data collection will be retrieved from individual databases of the countries included in the study and various studies and research cited throughout the study. The evolution of data collection will begin with an article linked to a study on aging inmates and evolve to a collection of researches, studies, and data sets putting a spotlight on chronic illness of elderly inmates. An alteration of data search was done to narrow the research from chronic illness to judicial policy and the effect on obesity and diabetes. Through the data collection process, the judicial policy relating to the elderly inmate and disease was very illuminating as there appears to be a direct link to judicial policy and obesity and diabetes among the elderly inmates globally.

Procedure

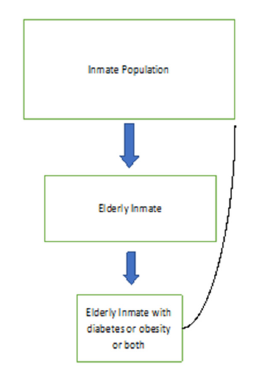

Figure 4:Multistage sampling.

The research sampling method that will be used in this study is multistage sampling. Please see Figure 4 for an example of multistage sampling. Multistage sampling is used when combining multiple methods for an appropriate and required sample [43]. Since the study will be looking at elderly inmates in various data sets in various geographic locations in various stages of obesity, diabetes, and time of confinement, the multistage sampling would appear to be the most logical method of sampling for this particular study. In simple terms, in multi-stage sampling, large population clusters are divided into smaller clusters in several stages to make primary data collection more manageable. This method allows for flexibility and is time-effective compared to most studies [43]. The samples will be taken from various studies and data sets consisting of inmates over the age of with the affliction of diabetes and obesity.

A maximum variation sampling method will be used to have a better understanding of how inmates globally are affected by similar conditions at different geographic locations under different judicial policies. Maximum variation sampling is what the name implies: a sample is made up of extremes. or is chosen to ensure a wide variety of participants [44].

Data analysis

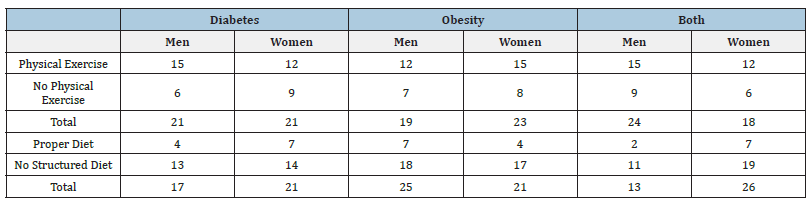

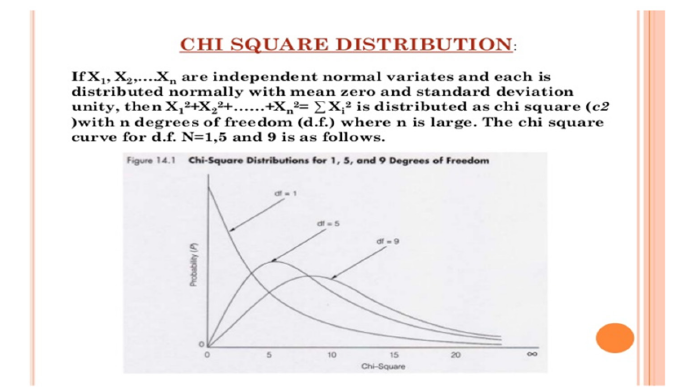

A multivariate qualitative analysis approach will be taken with the study. Multivariate analysis, in a broad sense, is the set of statistical methods aimed simultaneously to analyze datasets. Furthermore, discriminant analysis will provide rules for classifying new observations of the group of origin based on the information provided by the values it takes from the independent variables [45]. Moreover, the analysis completed through this approach will help determine the viability of future research as well as possible directions for future research. The Chi-squared test will be used to compare the different cohorts of the elderly inmates. The Chi-square statistic is a non-parametric (distribution-free) tool designed to analyze group differences when the dependent variable is measured at a nominal level. Advantages of the Chi-square include its robustness with respect to distribution of the data, its ease of computation, the detailed information that can be derived from the test, its use in studies for which parametric assumptions cannot be met, and its flexibility in handling data from both two group and multiple group studies (Table 1 & Figure 5) [46].

Table 1:Multivariate relationship: diabetes and obesity, age, and gender.

Figure 5:An example of the Chi-Squared test.

Summary

Finding will be critical for the future treatment recommendations and future research concerning the elderly inmates and diabetes and obesity. Theoretical validation is the most fundamental aspect of managing quality in interpretive research. Theoretical validation implies a continuous focus on the question of whether the theories or the knowledge produced appropriately correspond to the empirical reality observed [47]. This proposition also highlights that, while the notion of theoretical validation focuses on the generation of abstract knowledge, the consideration of this aspect needs to span the entire research process [48-60]. Furthermore, the theoretical validation that this study will seek is the direct correlation between judicial policies and the prevalence of diabetes and obesity. Moreover, with proper diet control, stress management, and physical exercise that a reduction within the penal system could possibly take place [61-71].

References

- ADA (2005) Diabetes management in correctional institutions. Diabetes Care 18(3): 151-158.

- Osborne (2015) The high costs of low risk: the crisis of America's aging prison population. Osborne Association.

- Ogden CC, Curtin L, Mcdowell M, Tabak C (2006) Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States. Advanced Data from Vital and Health Statistics.

- WHO (2018) Obesity. World Health Organization.

- Herbert K, Plugge E, Foster C, Doll H (2012) Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases in prison populations worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet 379(9830): 1975-1982.

- Wolff NS, Shi J, Fabrikant N, Schumann BE (2012) Obesity and weight-related medical problems of incarcerated persons with and without mental disorders. Journal of Correctional Care 18(3): 219-232.

- Laakso M, Pyörälä K (1985) Age of onset and type of diabetes. Diabetes Care 8(2): 114-117.

- Bruce DG, Chisholm DJ, Storlien LH, Kraegen EW (1988) Physiological importance of deficiency in early prandial insulin secretion in non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Diabetes 37(6): 736-744.

- Gregg EW, Beckles GL, Williamson DF, Leveille SG, Langlois JA, et al. (2000) Diabetes and physical disability among older U.S. adults. Diabetes Care 23(9): 1272-1277.

- Feeley MM, Rubin EL (1998) Judicial policy making and the modern state: How the courts reformed America's prisons. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, UK.

- Hammett TM (2006) HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases among correctional inmates: transmission, burden, and an appropriate response. American Journal of Public Health 96(6): 974-978.

- Liu B (2004) UCLA law review: A prisoner’s right to religious diet beyond the free exercise clause.

- Arnold H (2016) The prison officer. Arnold H (Ed.), Handbook on prisons. Routledge, Oxford, USA.

- Eisen L (2014) Paying for your time: How charging inmates fees behind bars may violate the excessive fines clause. Loyola Journal of Public Interest Law 15(2): 319.

- Booles K (2009) Breaking down barriers: diabetes care in prisons. Journal of Diabetes Nursing 13(10): 388.

- Weiner R (1982) Management strategies to reduce stress in prison - Humanizing correctional environments. In: Johnson R (Ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, UK.

- Dietz WH, Benken DE, Hunter AS (2009) Public health law and the prevention and control obesity. The Milbank Quarterly 87(1): 215-227.

- Lin X, Zhang X, Guo J, Roberts CK, McKenzie S, et al. (2015) Effects of exercise training on cardiorespiratory fitness and biomarkers of cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. American Heart Association 4(7): e002014.

- Anton SD, Karabetian C, Naugle K, Buford TW (2013) Obesity and diabetes as accelerators of functional decline: can lifestyle interventions maintain functional status in high-risk older adults? Exp Gerontology 48(9): 888-897.

- Napora J (2013) Managing stress and diabetes. American Diabetes Association.

- Edwards L (2005) Managing diabetes in correctional facilities. Diabetes Spectrum 18(3): 146-151.

- Douglas N, Plugge E, Fitzpatrick R (2009) The Impact of imprisonment on health: what do women prisoners say? Journal of Epidemiol Community Health 63(9): 749-754.

- Choudhry K, Armstrong D, Dregan A (2018) Systematic review into obesity and weight gain within male prisons. Obesity Research and Clinical Practice 12(4): 327-335.

- Carlson PG, Garrett JS (1999) Prison and jail administration: Practice and theory. Jones and Bartlett.

- Fazel S, Hope T, O'Donnell I, Piper M, Jacoby R (2001) Health of elderly male prisoners: worse than the general population, worse than younger prisoners. Age Ageing 30(5): 403-407.

- Travis J (2014) The growth of incarceration in the United States: Exploring causes and consequences. Atlanta: National Academics Press.

- Howe P (2003) Cash hungry states cutting prison fare. Seattle Times, USA.

- Silverman OL, Lopez-Ridaura R, Servan-Mori E, Bautista-Arredondo S, Bertozzi SM (2015) Cross-sectional association between length of incarceration and selected risk factors for non-communicable chronic diseases in two male prisons of Mexico City. PLOS One 10(9): e0138063.

- Binswanger IA, Merrill JO, Krueger PM, White MC, Booth RE, et al. (2010) Gender differences in chronic medical, psychiatric, and substance-dependence disorders among jail inmates. American Journal of Public Health 100(3): 476-482.

- Firth LC, Sazie E, Hedberg K, Drach L, Maher J (2015) Female inmates with diabetes: Results from changes in a prison food environment. Women's Health Issues 25(6): 732-738.

- Selye H (1956) The stress of life. McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, USA.

- Massoglia M (2008) Incarceration as exposure: The prison, infectious disease, and other stress-related illnesses. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 49(1): 56-71.

- Thoits PA (1995) Stress, coping, and social support process: Where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 35: 53-79.

- Fremont A (2000) Social and psychological factors, physological processes, and physical health. In: Bird CF (Ed.), Handbook of Medical Sociology. Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 5: 334-352.

- Halfon N, Hochstein M (2002) Life course health development: An integrated framework for developing health, policy, and research. Milbank Quarterly 80(3): 433-479.

- Karlamangla AS (2006) Reduction in allostatic load in older adults is associated with lower all-cause mortality risk. Psychosom Med 68(3): 500-507.

- Martins I (2016) Anti-aging genes improve appetite regulation and reverse cell senescence and apoptosis in global populations. Advances in Aging Research 5: 9-26.

- Paris M (2001) Legal mobilization and the politics of reform: Lessons from school finance litigation in Kentucky, 1984-1995. Law and Social Inquiry 26(3): 631-684.

- Schoenfeld H (2010) Mass incarceration and the paradox of prison conditions litigation. Journal of Law ad Society Assoc 44(3): 731-767.

- Wildeman C (2016) Incarceration and population health in wealthy democracies. Criminology 54(2): 360-382.

- Bailey G, Dunlop E, Forsyth P (2022) A qualitative exploration of the enablers and barriers to the provision of outpatient clinics by hospital pharmacists. International journal of clinical pharmacy 44(4): 1013-1027.

- Salkind NJ (2010) Encyclopedia of research design. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, USA.

- Setia MS (2016) Methodology series module 5: Sampling strategies. IJD 61(5): 505-509.

- WHO (2016) Variation sampling. World Health Organization.

- Mengual-Macenlle N, Marcos PJ, Golpe R, González-Rivas D (2015) Multivariate analysis in thoracic research. Journal of Thoracic Disease 7(3): E2-E6.

- Miller D (2021) A theory of a theory of the smartphone. International Journal of Cultural Studies 24(5): 860-876.

- Hammersley M (1992) Routledge revivals: What's wrong with ethnography? Methodological explorations (1st ), Routledge, UK.

- Auerhahn K (2002) Selective incapacitation, three strikes, and the problem of aging prison populations: Using simulation modeling to see the future. Criminology 1(3): 353-388.

- Binswanger IA, Krueger PM, Steiner JF (2009) Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among jail and prison inmates in the USA compared with the general population. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 63(11): 912-919.

- Carr AA, Amrhein C, Dery R (2011) Research protections for diverted mentally ill individuals: Should they be considered prisoners? Behavioural Sciences and the Law 29(6): 796-805.

- Cislo AM, Trestman R (2013) Challenges and solutions for conducting research in correctional settings: The U S experience. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 36(3-4): 304-310.

- Colditz G, Willett WC, Rotnitzky A, Manson JE (1995) Weight gain as a risk factor for clinical diabetes mellitus in women. Ann Intern Med 122(7): 481-486.

- Condon L, Gill H, Harris F (2007) A review of prison health and its implications for primary care nursing in England and Wales: The research evidence. J Clin Nurs 16(7): 1201-1209.

- Creswell J (2013) Review of the literature. In Creswell, research design. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA.

- Fazel S, Bains P, Doll H (2006) Substance abuse and dependence in prisoners: A systematic review. Addiction 101(2): 181-191.

- Fish JE, Ettner S, Ang A, Brown AF (2010) Association of perceived neighbourhood safety on body mass index. American Journal of Public Health 100(11): 2296-2303.

- lanagan PB (1996) Prison disease and blood transfusion. Transfusion Medicine 6: 213-215.

- Freudenberg N (2001) Jails, prisons, and the health of urban populations: A review of the impact of the correctional system on community health. Journal of Urban Health 78(2): 214-235.

- Gallagher D, Heymsfield SB, Heo M, Jebb SA, Murgatroyd PR, et al. (2000) Healthy percentage body fat ranges: An approach for developing guidelines based on body mass index. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 72(3): 670-694.

- Gates ML, Bradford RK (2015) The impact of incarceration on obesity: are prisoners with chronic diseases becoming overweight and obese during their confinement? Journal of Obesity.

- Harding G, Gantley M (1998) Qualitative methods: beyond the cookbook. Family Practice 15(1): 76-79.

- Kalist DE, Siahaan F (2013) The association of obesity with the likelihood of arrest for young adults. Economics of Human Biology 11(1): 8-17.

- Leddy AM, Schulkin J, Power ML (2009) Consequences of high incarceration rate and high obesity prevalance on the prison system. Journal of Correct Health Care 15(4): 318-327.

- Luallen J, Cutler C (2017) The growth of older inmate populations: How population aging explains rising age at admission. J Gerontol Psychol Sci Soc Sci 72(5): 888-900.

- Price GN (2009) Obesity and crime: Is there a relationship? Economic Letters 103(3): 149-152.

- Psick ZS, Simon J, Brown R, Ahalt C (2017) Older and incarcerated: Policy implications of aging prison populations. International Journal of Prisoner Health 13(1): 57-63.

- Schwartz MB, Puhl R (2003) Childhood obesity: A social problem to solve. Obesity Reviews 4(1): 57-71.

- Tariq S, Woodman J (2013) Using mixed methods in health research. JRSM 4(6): 2042533313479197.

- Wang HN (2016) Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388(10053): 1459-1544.

- Warren J (2008) One in 100: Behind bars in America 2008. Washington DC: The Pew Cgaritable Trusts.

- Zheng WM, McLerran DF, Rolland B, Zhang X, Inoue M, et al. (2011) Association between body-mass index and risk of death in more than 1 million Asians. New England Journal of Medicine 364(8): 719-729.

© 2025 Heath D Harllee. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)