- Submissions

Full Text

Investigations in Gynecology Research & Womens Health

Cerebral Sinus Venous Thrombosis in Postpartum Period: A Case Report

Minoo Movahedi1, Farnaz Baba Haji Meybodi1* and Narjes Khalili2

1Department of Gynecology and Obstetrician, Iran

2Department of Community and Family Medicine, Iran

*Corresponding author:Farnaz Baba Haji Meybodi, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrician, Iran

Submission:February 02, 2022;Published: March 22, 2022

ISSN: 2577-2015 Volume4 Issue3

Abstract

A 24-year-old woman at 41 weak gestational age underwent epidural anesthesia and normal vaginal delivery. After 7 days of delivery, patient referred to our hospital with severe headache, left paresthesia, and tonic-clonic seizure. During this period, the patient suffered a headache that was attributed to the epidural anesthetic. Radiologic assessments showed thrombosis at superior sagittal sinus. Cerebral Sinus Venous Thrombosis (CSVT) is a rare disease. The annual incidence is estimated to be about 5 per million, which is affected by age, sex, and areas. Pregnancy, postpartum, use of oral contraceptive and abortions are major risk factors. It is difficult to diagnose the disease from eclampsia during pregnancy and puerperium. Due to the high mortality rate of this disease, timely diagnosis and treatment should be considered. Treatment with anticoagulants should be done immediately.

Keywords: Anti-coagulant; Cerebral thrombosis; Postpartum; Pregnancy

Introduction

Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis (CVST) is a rare condition. Although its precise incidence rate is unknown, its annual incidence is estimated at 5 per 1,000,000, with reports varying by age, gender and location [1]. Research reported an estimated annual incidence of 12.3 per 1,000,000 in Iran [2]. Currently, over 20,000 individuals in the United States are suffering from the complications and morbidities associated with CVST [3]. Numerous causes may result in sinus thrombosis, most notably infectious causes (microbial, viral, fungal and parasitic) followed by hormonal causes (pregnancy, postpartum period, use of oral contraceptives, androgen intake, abortion), malignancies, blood disorders, systemic diseases (nephrotic syndrome, polyarteritis nodosa, Wegner’s granulomatosis, Bechet’s disease, ulcerative colitis), trauma, medications, and dehydration. In 30% of cases, however, the etiology remains unidentified [4].

CVST occurs in 0.004-0.01 of pregnancies, accounting for 2% of all pregnancy-related strokes; its incidence is higher in the third trimester and the postpartum period [3]. This condition encompasses a wide spectrum of clinical symptoms, and the onset of symptoms varies greatly. In general, the most prominent clinical symptoms include headache, seizure, focal neurologic symptoms, papilledema, and lowered level of consciousness [5]. Because of the similarity symptoms of eclampsia and CSVT, it may be difficult to differentiate them, and so timely diagnosis and treatment of this potentially deadly disease is important [6].

Case Report

A 24-year-old woman (G1L1) referred at midnight to the hospital with mild pain for the purpose of termination of pregnancy. Her gestational age was 41w±4d according to sonography report and Last Menstrual Period (LMP). Her vital signs were normal. On physical examination, cervical dilation was 1 cm, effacement was poor, and the amniotic sac was intact. The patient underwent Oxytocin Challenge Test (OCT). As the result was negative, induction of labor with serum oxytocin was started. With 5cm cervical dilation and 50% effacement, the patient underwent epidural anesthesia. After the injection, the patient complained of severe headache which lasted about thirty minutes. Eventually, with the repetition of epidural anesthesia and continuation of induction, vaginal delivery with episiotomy was accomplished. The 1- and 5-minute Apgar scores of the newborn were 9 and 10, respectively. In the obstetric ward she complained again of severe headache which was relieved with analgesics.

The patient was discharged in good general condition. She occasionally suffered from mild headaches at home which were alleviated with analgesics. She had been diagnosed with hypothyroidism since a few years prior to her pregnancy, which was controlled by levothyroxine, and she was euthyroid. She did not have a history of other diseases, and other than supplements, she did not take any medication in the perinatal period. All clinical and para clinical examination was normal during her pregnancy. On the fifth day post labor, the patient referred to hospital with severe headache and perspiration. Vital signs were normal, and she was discharged with negative proteinuria and platelet count of 276,000. On the seventh day post labor, she suffered from paresthesia in the left hand, followed by two episodes of seizure one hour apart. The seizures were tonic-clonic in nature, involving the left side with upward gaze. She was admitted with a diagnosis of postpartum eclampsia and treated with magnesium sulfate.

As the seizures were repeated three more times, the patient received magnesium sulfate (2g/Kg), intravenous depakine (600mg), intravenous phenytoin (750mg), and intravenous phenobarbital (200mg) and she was transferred to another hospital, with an obstetric team and an anesthesiology technician. Her Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was 15/15 and her vital signs were blood pressure: 115/70mmHg, temperature: 37.7 ˚C, pulse rate: 105/min, respiratory rate: 26/min, and SpO2: 95%.

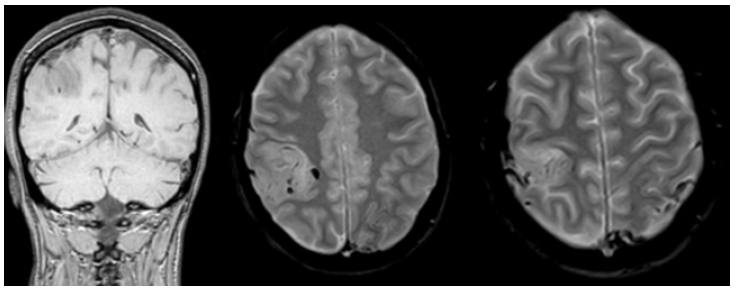

Magnesium sulfate was continued, and she was visited by neurology and neurosurgery services. Vital signs and all tests, including hematological, hepatic, renal and urinary, and coagulation tests as well as her abdominal and pelvic sonography findings were normal. Following consultation with the neurology service, the patient underwent emergency brain MRI and MRV±GAD with a CPR team, and subcutaneous heparin injection (5000 units twice a day) was prescribed for her. MRI and MRV revealed thrombosis in the superior sagittal sinus and both transverse sinuses. Thus, a diagnosis of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis was established (Figure 1). The patient was admitted to the neurology ward and treated with enoxaparin (60 units twice a day).

Figure 1: MRI showed evidence of thrombosis at superior sagittal sinus and partial thrombosis of both transverse sinuses. Bilateral superficial vein thrombosis at partial convexity is seen.

Discussion

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis poses a diagnostic challenge as clinical symptoms vary greatly. Severe headache in 70%, motor weakness in 38%, and coma in 45% of cases are observed [7]. Moreover, CVST is much more difficult to diagnose in patients who have received epidural anesthesia during labor and complain of headache immediately after delivery. With this clinical presentation, the patients are often treated with hydration and analgesics for headache induced by epidural anesthesia, which may delay the diagnosis of CVST until more severe and ominous symptoms manifest [3]. In our patient, the severe headaches were attributed to epidural anesthesia until she presented with tonicclonic seizures. Another group of patients with potentially delayed diagnosis are those with preeclampsia and CVST who present with seizures [8]. Such patients are empirically treated with magnesium sulfate and an MRI is requested only after more severe clinical symptoms begin to manifest.

The prognosis of CVST is quite diverse, ranging from complete recovery to death [9]. One review study indicated that clinical symptoms on admission are associated with prognosis and longterm outcomes. In patients presenting with headache alone at the time of treatment, the probability of better outcomes is 3.9 times, whereas for patients presenting with altered consciousness or coma, the risk of long-term complications is 3.6 times [3]. Indeed, the prognosis is highly influenced by the patient’s conditions and the etiology of the disease. Even optimal intervention or treatment may fail to save the life of a patient with poor prognosis [10]. Approximately 85% of patients who receive appropriate treatment will be discharged without neurologic complications. Mortality rate varies from 2.5% to 20% [1].

The sagittal sinus is the most frequently involved site in CVST. Depending on the location of the thrombosis, patients experience different neurologic symptoms. Seizures occur in 40% of cases, of which 50% are focal. [11]. Lowered level of consciousness is associated with poorer prognosis and higher mortality [1]. CVST is more common in women and affects women aged 25-35 years. Use of oral contraceptives (54.3%), hereditary hypercoagulability state (22.4%), and the postpartum period (20.1%) have been proposed as causative factors [7]. Women are at risk of thromboembolic events during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Chronologically, CVST is more frequent in the third trimester and the postpartum period. In postpartum period, dehydration and trauma may promote the hypercoagulable state. The risk of thrombosis in pregnancy is increased due to Cesarean section, delivery with instruments, trauma to the birth canal, or infection [12]. In our patient, the postpartum period was identified as a major risk factor.

Diagnosis based on clinical findings and imaging. Headache is the most common symptoms which is due to increased intracranial pressure. The headache pattern is different, range from cluster headache, migraine-like headache, exploding headache, chronic tension headache. Sometimes the headache in CSVT mimics subarachnoid hemorrhage, and idiopathic intracranial hypertension [13]. Radiologic findings play a critical role in diagnosing CVST. MRI (Magnetic resonance imaging) and MRV (Magnetic resonance venography) are recommended for pregnant women. CVST is most commonly observed in the superior sagittal sinus as well as the right and left transverse sinuses [1] as in the case of our patient.

Treatment includes anticoagulants and anticonvulsants in case of seizure. Heparin appears to be relatively safe for use during pregnancy, which does not pass through the placenta barrier. Serious side effects is heparin induced thrombocytopenia. Warfarin is contraindicated in pregnancy, as it passes through the placental barrier and may cause bleeding in the fetus. Enoxaparin is a low molecular weight heparin, which binds to and accelerates the activity of antithrombin III. It also reduces the risk of preeclampsia/ eclampsia recurrence, and does pass through the placenta [3,14]. Our patient was first treated with heparin and then enoxaparin. Due to repeated seizures, anticonvulsants were prescribed for this patient. In cases of progressive disease, lack of response to anticoagulant therapy, or risk of death, more invasive treatments, such as endovascular thrombolysis or surgical thrombectomy, are indicated. However, data is scarce on these invasive treatments in pregnancy or the postpartum period [3]. Vitamin K antagonists, such as warfarin, are recommended as long-term maintenance therapy. The duration of anticoagulant therapy is three months in case of present risk factors, or 6-12 months in idiopathic cases as well as patients with mild hereditary thrombophilia. For patients with recurrent venous sinus thrombosis or those who have experienced one episode but have severe thrombophilia, long term therapy is recommended [15].

Conclusion

CSVT is a rare condition with a wide spectrum of symptoms. Headache and seizures in postpartum period emphasize the importance of considering and evaluating differential diagnoses. Therefore, appropriate diagnostic modalities will guide correct diagnosis and treatment.

References

- Soydinc HE, Ozler A, Evsen MS, Sak ME, Turgut A, et al. (2013) A case of cerebral sinus venous thrombosis resulting in mortality in severe preeclamptic pregnant woman. Case Reports in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2013: 402601.

- Janghorbani M, Zare M, Saadatnia M, Mousavi S, Mojarrad M, et al. (2008) Cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis in adults in Isfahan, Iran: frequency and seasonal variation. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 117(2): 117-121.

- Kashkoush AI, Ma H, Agarwal N, Panczykowski D, Tonetti D, et al. (2017) Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in pregnancy and puerperium: A pooled, systematic review. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 39: 9-15.

- Saadatnia M, Fatehi F, Basiri K, Mousavi SA, Mehr GK (2009) Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis risk factors. International Journal of Stroke 4(2): 111-123.

- Munira Y, Sakinah Z, Zunaina E (2012) Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis presenting with diplopia in pregnancy: A case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports 6(1): 336.

- Tillery KMA, Belfort MA (2005) Eclampsia: morbidity, mortality, and management. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 48(1): 12-23.

- Ferro JM, Canhão P, Stam J, Bousser MG, Barinagarrementeria F (2004) Prognosis of cerebral vein and dural sinus thrombosis: results of the International Study on Cerebral Vein and Dural Sinus Thrombosis (ISCVT). Stroke 35(3): 664-670.

- Savage H, Harrison M (2008) Central venous thrombosis misdiagnosed as eclampsia in an emergency department. Emergency Medicine Journal 25(1): 49-50.

- Cantu C, Barinagarrementeria F (1993) Cerebral venous thrombosis associated with pregnancy and puerperium. Review of 67 cases. Stroke 24(12): 1880-1884.

- Renowden S (2004) Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. European Radiology 14(2): 215-226.

- Stam J (2005) Thrombosis of the cerebral veins and sinuses. New England Journal of Medicine 352(17): 1791-1798.

- Farzadfard MT, Foroughipour M, Yazdani S, Juibary AG, Rezaeitalab F (2015) Cerebral venous-sinus thrombosis: Risk factors, clinical report, and outcome. A prospective study in the Northeast of Iran. Caspian Journal of Neurological Sciences 1(3):27-32.

- Botta R, Donirpathi S, Yadav R, Kulkarni GB, Kumar MV, et al. (2017) Headache patterns in cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice 8(Suppl 1): S72-S77.

- Saposnik G, Barinagarrementeria F, Brown RD, Bushnell CD, Cucchiara B, et al. (2011) Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke 42(4): 1158-1192.

- Marwah S, Shailesh GH, Gupta S, Sharma M, Mittal P (2016) Cerebral venous thrombosis in pregnancy-a poignant allegory of an unusual case. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 10(12): QD08-QD09.

© 2022 Farnaz Baba Haji Meybodi. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)