- Submissions

Full Text

Global Journal of Endocrinological Metabolism

Socio-Demographic Characteristics Differences between Pregnant Women Living with Disability and Able Bodied in Kakamega County, Kenya

Consolata Namisi Lusweti*, Peter Wisiuba Bukhala and Gordon Nguka

Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology, Kenya

*Corresponding author: Consolata Namisi Lusweti, Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology, Kenya

Submission: September 22, 2018; Published: October 03, 2018

ISSN: 2637-8019Volume2 Issue4

Abstract

Objective: This study set out to compare the antenatal health and demographic factors as well as the pregnancy and delivery outcomes in women with disability and those without disability in Kakamega, Kenya.

Design: A population-based prospective case control study.

Setting: The study was done in 12 Sub County in Kakamega County.

Sample: The study used a multistage probability sampling design to identify the sub counties that would be case and control groups and purposeful and snow balling sampling technique to identify the pregnant women living with disability who in turn identified an able-bodied pregnant woman that she is accessible to (n=117).

Analysis: Data was analyzed through descriptive characteristic and chi-square tests of significance.

Main outcome measures: Health and socio-demography, issues of reproductive health and issues of access, safety and comfort with regards to antenatal care.

Result: A higher proportion of women with disability had spouses (57% vs. 100%), were of the age bracket 25-29 years (30.1% vs. 12.5%) and had primary education (53.8% vs. 75%) compared with women without disability, and pregnancy in women with disability was not planned (68.8% vs. 25%). Women with disability had experienced major maternal health problems (54.8% vs. 37.5%), attended antenatal clinic in their current pregnancy (69.9% vs. 91.7%) and had visited the antenatal clinic only once during current pregnancy (21.5% vs. 12.5%). Chi square tests showed that there was significant relationships between marital status χ2 (2, N=117)2.578, p=0.001, education χ2 (2, N=117) =3.912, p=0.097 and income χ2 (2, N=117)=7.404, p=0.039 with the status of disability.

Conclusion: Pregnant women with disability should be considered a risk group suggesting that better tailored pre- and intrapartum care and support are needed for these women because of low level of education, distorted family and longer time taken to access health facility.

Keywords: Disability; Maternity care; Pregnancy; Birth; Maternity survey

Introduction

According to Kenya’s Persons with Disabilities Act of 2003, “disability” means a physical, sensory, mental or other impairment, including any visual, hearing, learning or physical incapability, which impacts adversely on social, economic or environmental participation. Other types of disabilities are albinism and autism. The results from the 2009 Census (KNBS, 2010), indicate that the number of people with disabilities in Kenya at the time was 647,689 (3.4%) males and 682,623 (3.5%) females [1]. Some health conditions associated with disability result in poor health and extensive healthcare needs. Franklin [2] these special healthcare needs are due to the fact that WWDs are under-served by health programmes and promotions, for example screening for breast and cervical cancer, thereby increasing the risk of further disability mat later stages in life. This contravenes Article 25 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) which was adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2006 which reinforces the right of persons with disabilities to attain the highest standard of health care, without discrimination.

A woman with disability tends to be judged and found wanting in appearance, in comparison to the conventional stereotypes of ‘beauty’ in her culture. Franklin [2] states that women with disabilities are less likely to be married than men with disabilities. This is largely due to negative attitudes and stereotypes about what WWDs can or cannot do, particularly in societies where marriages are arranged by the elders and is a contract between the concerned families rather than the individuals. There are misconceptions that a woman with physical disability may not be competent in most spheres such as learning or being able to be in a gainful employment. World Bank [3] there is a strong link between poverty and disability. Poor people have a higher risk of acquiring a disability; they are more exposed to disabling diseases and conditions. At the same time, disability increases the possibility of falling into poverty by being excluded from participation of development initiatives. This cycle of disability and poverty must and can be broken. The World Bank estimates that 20 per cent of the world’s poorest people have some kind of disability and tend to be regarded in their own communities as the most disadvantaged. Women with disabilities are recognized to be multiply disadvantaged, experiencing exclusion on account of their gender and their disability [3].

To ensure a safe pregnancy and a healthy baby it is argued that healthcare professionals should focus more on women’s abilities than their disabilities and that care and communication should be about empowering women. Evidence from qualitative research suggests that maternity care needs have not been met for many pregnant disabled women. Many women with disabilities say they feel invisible in the healthcare system, stressing that their problems are not simply medical, but also social and political, and that access means more than mere physical accessibility. WHO [4] Because many women with disabilities face a great deal of unpredictability in their daily lives, they want care that is well planned, and which helps to eliminate the unexpected. Demographic factors of the both the women living with disability and normal women has to be considered when looking at maternal and neonatal health indicators. These included age, level of education, religious affiliation, number of pregnancies, her occupation status. According to Olsen et al. [5], the older women appeared to have an increased risk independent of number of pregnancies. This was not necessarily explained by obstetric factors alone, but also be due to other factors. There could have been a decrease of the general state of health among older women, or less active health-seeking behaviour, rendering them more at risk. This seemed reasonable when we looked at the causes of death among the cases. Of seven women struck by maternal death in the older age group, six died of malaria, while one died of other indirect obstetric causes. All had five or more pregnancies. In addition, younger women might have had husbands of higher educational level or with less reluctance to using modern health facilities.

PWDs in Kenya live in a vicious cycle of poverty due to stigmatization, limited education opportunities, inadequate access to economic opportunities and access to the labour market. The women with disabilities are more vulnerable to human rights violations through neglect and exclusion from political, sociocultural, civil and economic activities. They face discrimination in access to and utilization of public health facilities and services and are under-served in terms of healthcare information [6]. There are no special services to provide assistance to mothers with disabilities. They are often forced to rely on their families or engage someone whom they must pay for by themselves, to care for their children. The position of mothers with disabilities in the rural communities is even worse. There are no strategies or activities by state bodies or health care institutions that take into account the specific health needs of young girls and women with disabilities. Unfortunately, because of this, women do not receive even the basic primary health care services that are necessary for all children and young women [6]. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare socio-demographic characteristics of pregnant women living with disability and able-bodied pregnant women.

Theoretical Framework

Critical disability theory (CDT)

This study was guided by the critical disability theory (CDT) which was propounded by Oliver M [7]. This is an emerging theoretical framework for the study and analysis of disability issues. Hosking [8] This theory evolved from the work of scholars who formed the Frankfurt School, a term which refers to a group of Western Marxist social researchers and philosophers originally working in Frankfurt, Germany. Critical theory sees problems of PWDs explicitly as the product of an unequal society. It ties the solutions to social action and change. Notions of disability as social oppression mean that prejudice and discrimination disable and restrict people’s lives much more than impairments do. For example, the problem with public transport is not the inability of some people to walk but that buses are not designed to take wheelchairs. Such a problem can be “cured” by spending money to ensure that public transport is designed in such a way that it becomes accessible to persons with disabilities [9]. The impact of this critical theory on healthcare and research has tended to be indirect. It has raised political awareness, helped with the collective empowerment of PWDs and publicized their critical views on healthcare. It has criticized the medical control exerted over the lives of PWDs, such as repeated and unnecessary visits to clinics for impairments that do not change and are not illnesses in need of treatment. Finally, it suggests a more appropriate societal framework for providing health services to PWDs.

This radically different view is called the social model of disability, or social oppression theory. While respecting the value of scientifically based medical research, this approach calls for more research based on social theories of disability if research is to improve the quality of lives of the people with disabilities. The theory views the problems of people with disabilities explicitly as products of an unequal society. The discrimination aspects in the theory helped to explain the experiences of women with physical disabilities in accessing and utilizing healthcare services. This theory finds relevance in the factors that hinder women with physical disabilities from accessing and utilizing health services from public facilities.

Materials and Method

The study adopted quantitative methods. This was community based Prospective case control study. Data was collected using a structured questionnaire. The study targeted a sample of 117 women living with and without disability who are confirmed pregnant. The study used a multistage probability sampling design to identify the sub counties that would be case and control groups. Purposeful and snow balling sampling technique were used to identify the pregnant women living with disability who in turn identified an able-bodied pregnant woman that they are accessible to. Household surveys were done using structured questionnaires. Ten enumerators who were all Community Health Volunteers with previous experience on similar research were recruited and trained by the researcher for two days on how to use the research instrument and the easier way to collect data from the respondents. The inclusion criteria were all pregnant women in their first and second trimester age between 15-49 years and live in Kakamega County. Approval to carry out the study was obtained from Kakamega County Health director of health. Only those mothers, who met the study requirements, verbally consented and voluntarily signed the consent forms were enrolled into the study. Participants who could not write indicated their consent by a fingerprint. All mothers were assured of confidentiality.

Statistical Analyses

Schlomer et al. [10] outlined guidelines for best practices regarding the handling and reporting of missing data within research. Visual inspection of the data illustrated that missing data appeared to be missing at random. After visual inspection, in order to further examine the pattern of missing data, the researcher evaluated whether the data was missing completely at random (MCAR). The researcher utilized Little’s MCAR test which employs a chi-square statistical analysis and assumes the null hypothesis, that missing data is missing completely due to randomness [10]. In this case, failing to reject the null hypothesis indicates that the data was most likely not missing in a random way. For this study, Little’s MCAR test results showed that socio-demographic characteristics (χ2[112] =86.447, p=.965) was not significant indicating that the variables were missing completely at random, the researcher proceeded to address the missing data. To avoid reducing the variances of the scores by replacing missing items using subscale means, the missing data items were instead imputed using the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm within SPSS 23.

Data collected using the questionnaire was checked for consistency and accuracy of the responses, coded and analyzed using the version 23 of the SPSS statistical programme. Sociodemographic characteristics of both disabled and non-disabled women of reproductive age in Kakamega Central Sub county, Kenya was analyzed through descriptive statistics in which central tendencies and Chi-square tests of significance, extent of data dispassion and variability were calculated and presented on bar graphs and pie charts. Women who did not complete the questions in the survey relating to disability were excluded. For all comparisons between a specific disability group and non-disabled women the statistical significance level was set at p=< 0.01 Cross tabulations were undertaken to establish linkages between different variables.

Result

The summary of the findings of the study was based on the objective of the study. A total of 117comprising of 93 pregnant women living with disability and 24 able bodied pregnant women who reside within the twelve sub counties of Kakamega County, Kenya.

Household Characteristics

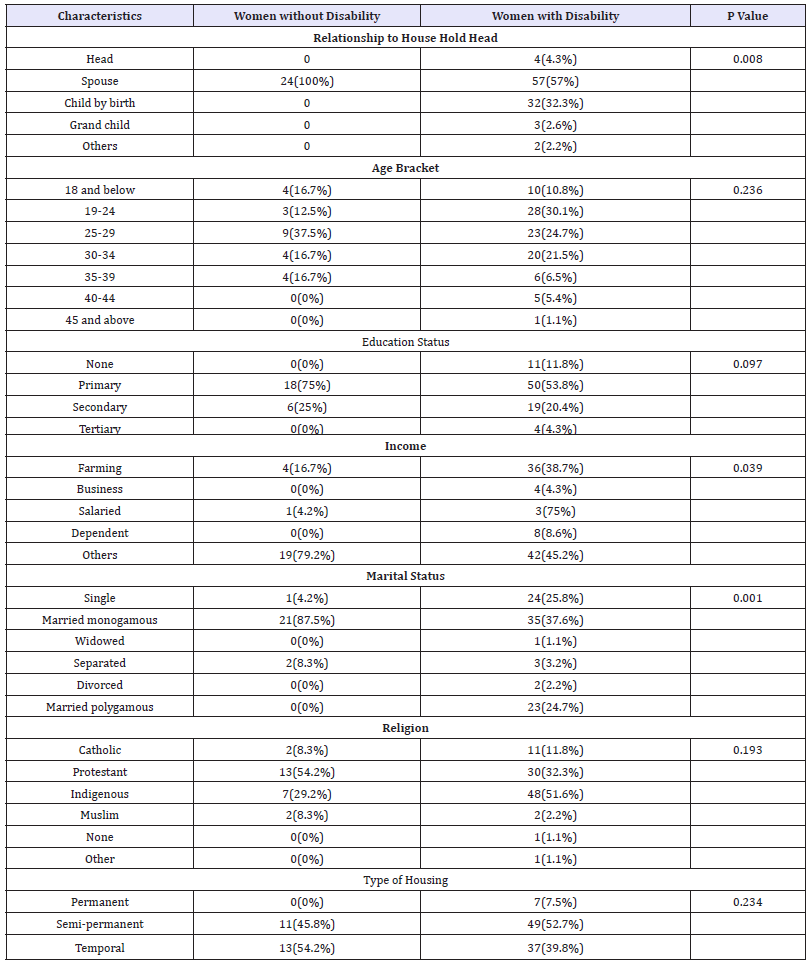

Table 1:Household characteristics.

*P values in bold are statistically significant.

Both the able-bodied women and women living with disability were spouses to the household head at 31.2% (24) and 68.8% (53) (Table 1) respectively of all the respondent. However, all the ablebodied women were spouses unlike 57% of the women living with disability were spouses while of the women living with disability, 32.3% relationship was child by birth and 4.3% were the heads, 3.2% were grandchildren, 2.2% children by other relationship and 1.2% were other. This indicates that this study established that unlike the able bodies women, women living with disability have distorted families. According to the χ2 test of independence, the difference was statistically significant with a χ2 (5, N=117) =6.463, p=0.008 so we can conclude that there is a difference in the relationship with the household head between the pregnant women living with disability and able-bodied women. Majority of the ablebodied women and women living with disability attained primary education at 26.5% (18) and 76.5% (50) (Table 1) respectively of all the respondent. This was also the findings within the status whereby among the able-bodied women 75% attained primary education while among the women living with disability it was 58.1% However among the women living with disability, 9.4% did not have any form of education unlike all the able-bodied women had some education. This study established that women living with disability had lower level of education than the able-bodied women. According to the χ2 test of independence, the difference was statistically insignificant with a χ2 (4, N=117) 0.887, p=0.097 so we can conclude that there is no a difference in the education status between the pregnant women living with disability and ablebodied women in Kakamega County.

Majority of both the able-bodied women and women living with disability were at the age bracket of (25-29) at 37.5% (9) and 24.7% (23) respectively for all the respondent. However, below 18years of age, 71.4% (Table 1) of women living with disability unlike 28.65 of able-bodied women were already pregnant. Both the able-bodied women and women living with disability were majorly dependent on their source of income However the women living with disability had a bigger percentage of dependents 52.1% (61) than the ablebodied women 31.1% (19). Majority who were not dependents on both statuses were farmers at 38.7% (36) for people living with disability and 16.7% (4) for able bodied women while within the status, none of the women living with disability was a business woman. This indicates that this study established that unlike the able bodies women, majority of women living with disability are dependents. According to the χ2 test of independence, the difference was statistically significant with a χ2(4, N=117)=6.462, p=0.039 so we can conclude that there is a difference in the sources of income between the pregnant women living with disability and able-bodied women.

Majority of the able-bodied women and women living with disability are married monogamous at 37.5% (21) and 62.5% (35) respectively of all the respondent. This was also the findings within the status whereby among the able-bodied women 87.5% were in a monogamous marriage while among the women living with disability it was 62.5% However none the able bodied was widowed, divorced nor even in a polygamous marriage unlike women living with disability 25.8% were single parents, 2.2% of them were divorced. 3.2%, separated and even 24.7% polygamous marriage. 54.2% (13) able bodied women lived in temporal houses while majority 81.7% (71) women living with disability were living in Semi-permanent houses (Table 1).

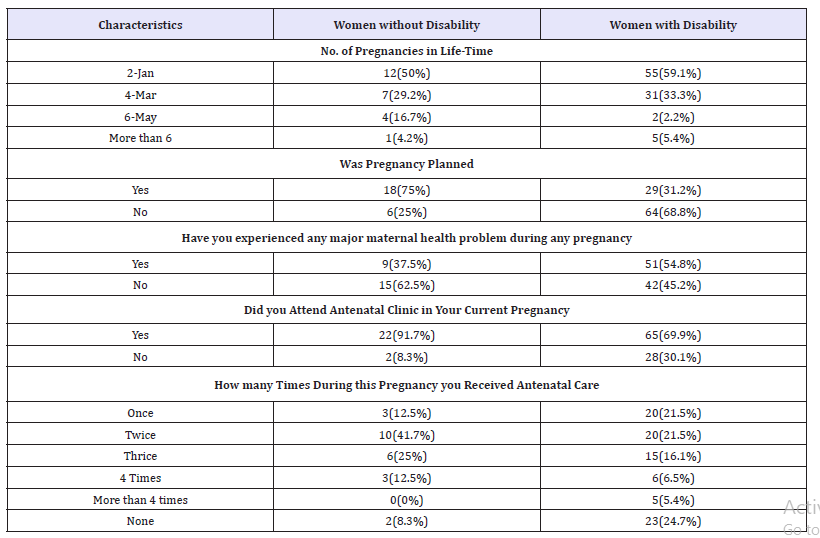

None one the able-bodied women lived in a permanent house unlike 7.5% (7) lived in permanent houses. However, from the previous findings 79.2% (19) of women living with disability were dependents, it is an indication that the houses might not be really theirs, but the houses belong to their bread winner. This study established women living with disability have a higher living standard than the able-bodied women. According to the χ2 test of independence, the difference was statistically insignificant with a χ2 (2, N=117)2.578, p= 0.234, so we can conclude that there is no a difference in the type of housing between the pregnant women living with disability and able-bodied women. Of the total respondents, among the able-bodied women, 38.3 (18) had planned for the pregnancy while 8.6% (6) had unplanned pregnancies unlike the women living with disability, 61.7% (29) had planned pregnancy while 91.4% (64) had unplanned pregnancy. Within the status, majority of the able-bodied women had planned pregnancy at 75% (18) unlike majority of women living with disability who had unplanned pregnancy at 68.8% (64).

The researcher also asked questions of preparatory service and reproductive health. Of the total respondents, among the ablebodied women, 38.3% (18) had planned for the pregnancy while 8.6% (6) had unplanned pregnancies unlike the women living with disability, 61.7% (29) had planned pregnancy while 91.4% (64) had unplanned pregnancy (Table 2). Within the status, majority of the able-bodied women had planned pregnancy at 75% (18) unlike majority of women living with disability who had unplanned pregnancy at 68.8% (64). This study established women living with disability have unplanned pregnancies unlike the able-bodied women. According to the χ2 test of independence, the difference was statistically highly significant with a χ2 (1, N=117) 15.240, p< 0.001 so we can conclude that there is a difference in planned pregnancy between the pregnant women living with disability and able-bodied women. Majority of both the able-bodied women and women living with disability confirmed to have attended ANC at 25.3% (22) and 74.4% (87) respectively of all the respondent. However, within the status, 91.7% of able-bodied women and 69.9% of the women living with disability confirmed to have attended ANC. This study established that more able-bodied women unlike women living with disability confirmed to have attended ANC.

Table 2:Reproductive health.

*P values in bold are statistically significant

Of the total respondent, 33.3% (3) were the able-bodied women while 66.7(6) were women living with disability Both the able-bodied women and women living with disability. None of the able-bodied women attended more than four times unlike 5.4% (5) who attended ANC clinic more than four times. Majority of the able-bodied women Attended ANC clinic twice which was 41.7% (10) while majority of women living with disability attended ANC clinic once or twice at 21.5% both. This indicates that this study established that both the able-bodied women, women living with disability attend to ANC clinic. According to the χ2 test of independence, the difference was statistically insignificant with a χ2(6, N=117) =10.278, p=0.113 so we can conclude that there is no difference in the relationship with the number of ANC attendants between the pregnant women living with disability and able-bodied women. Majority of able-bodied women take between 31mins-1hr to reach the nearest health facility on foot at 31.3% (15) unlike majority women living with disability who take over one hour at 82.6% (38) (Table 3).

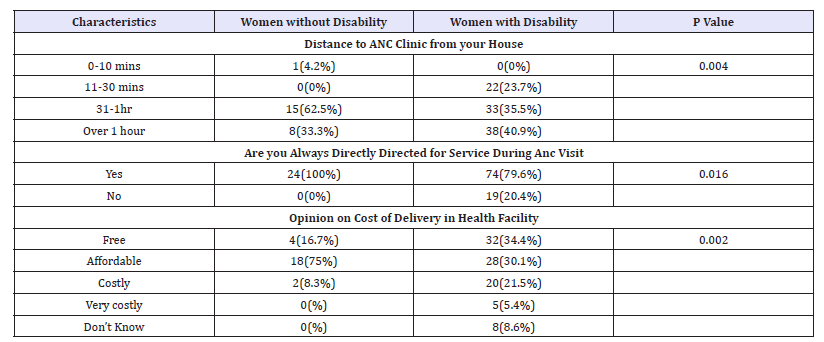

Table 3:Safety and comfort.

*P values in bold are statistically significant

Also, within the status, 62.5% able bodied women take between 31mins-1hr to reach the nearest health facility while 40.9% the women living with disability take over one hour at 82.6% (38). Also, within the status, 62.5% able bodied women take between 31mins-1hr to reach the nearest health facility. However, none of the women living with disability take 0-10mins to the nearest health facility unlike 4.2% of the able-bodied women who use similar time of 1-10mins to reach the nearest health facility. This indicates that unlike the able-bodied women, women living with disability take longer time to reach the nearest health facility. According to the χ2 test of independence, the difference was statistically significant with a χ2(3, N=117)=13.221, p=0.004 so we can conclude that there is a difference in the relationship in time taken to reach the nearest health facility on foot between the pregnant women living with disability and able-bodied women.

Both the able-bodied women and women living with disability confirmed that were always correctly directed for service in ANC visits during the pregnancy at 24.5% (24) and 75.5% (74) respectively of the entire respondent (Table 3). However, all the ablebodied women were always correctly directed for service in ANC visits during the pregnancy at 100% (24) unlike only 79.6% (74) of the women living with disability were always correctly directed for service in ANC visits during the pregnancy. This study established that unlike the able bodies women, women living with disability sometimes were not always correctly directed for service in ANC visits during the pregnancy with 20.4% (19). According to the χ2 test of independence, the difference was statistically significant with a χ2 (1, N=117) =5.854, p=0.016 so we can conclude that there is a difference in the relationship with correct direction for service in ANC visits during the pregnancy between the pregnant women living with disability and able-bodied women. While the majority of able-bodied women hold on opinion that the cost of delivery in the health facility is affordable at 39.1% (18), Majority of women living with disability have the opinion that the cost of delivery in the health facility is free at 34.4% (32) of the total respondent.

However, within the status all the able-bodied women seem to have an opinion on cost and none of them believe that it is very costly unlike women living with disability where 8.6% (8) did not have an opinion on cost of delivery whereas 5.4% (5) believed that health facility delivery was very costly. According to the χ2 test of independence, the difference was statistically significant with a χ2 (4, N=117) =16.845, p=0.002 so we can conclude that there is a difference in opinion on the cost of delivery in the health facility the pregnant women living with disability and able-bodied women.

Discussion

This study shows several differences between women with disability and women without disability during pregnancy and childbirth. The current study found that, 55% of the disabled women reported to have experienced major maternal health problems during pregnancy. This is consistent with a study in USA by Lisa et al. that found out across all women, regardless of pregnancy, women with disability are significantly more likely to report fair or poor general health than are other women: 35.0% versus 4.6%. In agreement also, is a study by Monika Mitra et al. 2015 that revealed women with disabilities reported significant disparities in their health care utilization, health behaviors and health status before and during pregnancy and during the postpartum period. Compared to nondisabled women, they were significantly more likely to report stressful life events and medical complications during their most recent pregnancy, were less likely to receive prenatal care in the first trimester, and more likely to have preterm births (13.4%; 95% CI, 11.6-15.6 compared to 8.9%; 95%CI, 8.5-9.3 for women without disabilities) and low birth weight babies (10.3%; 95% CI, 9.4-11.2 compared to 6.8%; 95% CI, 6.8-6.9). In agreement also, is a study by Christine et al. 2017 that showed that all women with disability who have had the experience of giving birth to a child or children faced immense challenges in childbearing.

The current study found significant association between disability and number of pregnancies, with majority of women reporting to have had one or two pregnancies in their lifetime. This is consistent with a study done by Gudlavalleti [11] that found a significantly lower proportion of women with disability experienced pregnancy (36.8%) compared to women without a disability (X2-16.02 P< 0.001). However, this study found that women with disability had more living children compared to women without a disability. The current study also found that 62.5% of the disabled women lived an hour from the health facility. These findings are consistent with the findings by John et al. [12] that found although women with disability do want to receive institutional maternal healthcare, their disability often made it difficult for such women to travel to access skilled care, as well as gain access to unfriendly physical health infrastructure.

The study found that majority of women living with disability were dependents 52.1% (61). This is consistent with the findings of Titaley et al. [13], that found poverty was a major factor influencing people’s decision-making about health services. However, with regard to the cost of delivery, majority of women living with disability 34.4% (32) had the opinion that the cost of delivery in the health facility is free. An interesting finding is that majority of the able-bodied women 54.2% (13) lived in temporal houses while majority 81.7% (71) women living with disability were living in Semi-permanent houses. The study also found that majority of the able-bodied women and women living with disability attained primary education at 26.5% (18) and 76.5% (50) respectively. A study done by Gabrysch et al. [14] found out that; lower level of mother’s education, mother’s occupation other than office work, lower yearly income, lower amenity score status and the long distance to maternity hospital with facilities for caesarean section, are all statistically significantly associated with a higher prevalence proportion of home delivery.

The current study also found that majority of the able-bodied women and women living with disability are married monogamous at 37.5% (21) and 62.5% (35) respectively. In addition, the current study found that majority of women with disability were of age 25-29 years and slightly older than their counterparts who were of age bracket 19-24. These findings are consistent with finding from a study done by Grue & Tafjord L [15] that found out, women with disabilities were slightly older and less likely to have partners. Similar findings have also been described in a review. The current study found that only 5.4% of women living with disability attended the ANC clinic more than four times. A few studies have tried to give reasons for this observation. Findings from a study in Norway, involving 21 women with physical disabilities, addressed the social barriers that faced such women, suggesting that negative attitudes and limited knowledge and experience among health care professionals prevent women from receiving the perinatal care to which they are entitled [15]. This increases the risk of women with disability to experience adverse pregnancy outcomes. Studies have found that Increased risks of instrumental delivery and adverse pregnancy outcomes have been reported in women with physical disabilities and longstanding conditions [16,17]. Finally, the current study found that both the able-bodied women and women living with disability received advice on where to deliver at 28.2%(24) and 71.8% (61) respectively. However, a study that was done found that services providing maternity care may not be equipped to deal with the needs of women with disabilities, both practically and in organizational terms [18]. This could be a possible explanation why low rates of ANC attendance were noted.

Conclusion and Recommendation

The findings will contribute to maternity services more satisfactorily pinpointing the required actions in caring for pregnant women with different types of disability and in training staff to support women with a wide range of conditions [19]. The findings from this study may enable maternity service providers to more satisfactorily pinpoint the required actions in caring for pregnant women with disability. Further research should target the experience, use of services and needs of women with different and multiple disabilities from diverse groups, using qualitative as well as quantitative methodologies. It could also include research on the role of partners and level of engagement. Audit and review of maternity services by healthcare providers should include a focus on the needs of women with disabilities represented by the different groups in this study. The implications for practice include taking the opportunities for training staff and improving aspects of maternity care for disabled women, namely in support and communication and infant feeding. This could contribute to improved outcomes for both women and babies and which could facilitate greater empowerment of the women receiving care.

References

- Republic of Kenya (2010) Constitution of Kenya 2010.

- Franklin P (1977) Impact of disability on the family structure. Social Security Bulletin 40(5): 3-18.

- World Bank Report (2010).

- WHO (2013) Health Report.

- Olsen BE, Hinderaker SG, Bergsjø P, Lie RT, Olsen OH (2002) Causes and characteristics of maternal deaths in rural northern Tanzania. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 81(12): 1101-1109.

- NGO Shadow Report to the UNCEDAW Committee (2004) On the implementation of CEDAW and women’s human rights in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

- Oliver M (1996) Understanding disability: From theory to practice. The Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare 23(3): 1-3.

- Hosking D (2008) Critical disability theory, paper presented at the 4th Biennial Disability Studies Conference, Lancaster University, UK.

- Devlin R, Pothier D (2005) Introduction: Toward a critical theory of dis-citizenship. In: Devlin R, Pothier D (Eds.), Critical Disability Theory: Essays in Philosophy, Politics, Policy, and Law, University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver, Canada.

- Schlomer GL, Bauman S, Card NA (2010) Best practices for missing data management in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology 57(1): 1-10.

- Gudlavalleti VSM, Neena J, Jayanthi S (2014) Reproductive health of women with and without disabilities in South India, the SIDE study (South India disability evidence) study: a case control study. BMC Women’s Health 14: 146.

- John KG, Easmon O, Bernard O, Anthony KE, Augustine A, et al. (2016) Challenges women with disability face in accessing and using maternal healthcare services in Ghana: A qualitative study. Plos One 11(6): e0158361.

- Titaley CR, Hunter CL, Dibley MJ, Heywood P (2010) Why do some women still prefer traditional birth attendants and home delivery? A qualitative study on delivery care services in West Java Province, Indonesia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 10: 43.

- Gabrysch S, Campbell OM (2009) Still too far to walk: literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 9(1): 34.

- Grue L, Tafjord LK (2002) Doing motherhood: some experiences of mothers with physical disabilities. Disabil Soc 17(6): 671-683.

- Signore C, Spong CY, Krotoski D, Shinowara NL, Blackwell SC (2011) Pregnancy in women with physical disabilities. Obstet Gynecol 117(4): 935-947.

- Chen YH, Lin HL, Lin HC (2009) Does multiple sclerosis increase risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes? A population-based study. Mult Scler 15(5): 606-612.

- Gavin N, Benedict M, Adams M (2006) Health service use and outcomes among disabled medicaid pregnant women. Womens Health Issues 16(6): 313-322.

- Canti V, Castiglioni MT, Rosa S, Franchini S, Sabbadini MG (2012) Pregnancy outcomes in patients with systemic autoimmunity. Autoimmunity 45(2): 169-175.

© 2018 Consolata Namisi Lusweti. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)