- Submissions

Full Text

Gerontology & Geriatrics Studies

Health Vulnerability Factors of Asian Migrant Population

James Paul Pandarakalam*

Consultant Psychiatrist, PANMED Health Care, Nr Gandhi University, India

*Corresponding author:James Paul Pandarakalam, Consultant Psychiatrist, PANMED Health Care, Nr Gandhi University, Athirampuzha-686562, Kottayam, Kerala, India

Submission: November 18, 2024; Published: January 07, 2025

ISSN 2578-0093Volume9 Issue 3

Abstract

The migration of young people from Asian countries, especially India, to the UK, other European nations, Canada and the US is largely driven by dissatisfaction with local job prospects and the desire for better employment opportunities. Kerala, known for its high literacy rates and educational focus, has become a major source of migrants, many of whom work in healthcare and information technology. However, migration also brings significant health risks, especially related to cardiovascular diseases. Research indicates that South Indian migrants, unaccustomed to colder climates, may be more vulnerable to heart issues, with higher mortality rates in areas like the Northwest of the UK, which has a large South Asian population. Additionally, the migration process itself can exacerbate health challenges, including stress, dietary changes and complications during the adjustment period. Migrants from warmer climates, such as South India, may struggle with immune system adaptation to colder weather countries and limited sunlight exposure in the UK and other colder regions of the world increases the risk of vitamin D deficiency, further compounding health problems. These issues were particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, where South Asians faced worse health outcomes. Despite these challenges, Kerala migrants have significantly contributed to the UK’s healthcare sector, with over 32,000 Indian nationals working in the NHS as of 2021. The health risks faced by migrants highlight the need for informed decision-making and robust support systems to address health challenges, especially for elderly returnees. This paper examines health risks such as access to healthcare, mental health, infectious diseases and chronic conditions and emphasizes the importance of tailored public health interventions and policies to address these challenges so as to promote health equity for migrants everywhere in the world.

Keywords:Migration; Cardiovascular health; Cold weather; Immune system; Vitamin D deficiency; COVID-19

Introduction

Migration is a complex, multifaceted phenomenon that can lead to profound changes in the health and well-being of individuals. Asian migrants, a rapidly growing demographic globally, face a range of health challenges influenced by factors both pre-existing in their home countries and emerging in their new environments. These health vulnerabilities are often underrepresented in public health research and policy, contributing to disparities in health outcomes. This paper examines the key factors that influence the health of migrant populations and suggests strategies to address these challenges. The young people in Asia are enraged with the employment system in their countries and the employed people are frustrated that they do not get any job satisfaction. There are other mitigating factors for this exodus of migration of Asian youths. But all migrations should be an informed choice. Migrants should be made aware of what they will have to face in the host countries in the long run before they set off to foreign countries for greener pastures. Indian citizens have ranked the highest in number among non-EU immigrants in the UK for several years. This continued to be the case in spite of the Covid pandemic hitting the world in 2020. Part of the reason, Indians are welcomed in UK. is due to the non-violent image Gandhi has created among the British people. Indians in UK. were proud of their prime minister with an Indian ancestry. In general, Indian migrants have relatively a good reputation as hardworking people. Migrants from Kerala, a southern state of India, have been attracted to healthcare making valuable contribution to the NHS. There are more than 32,000 Indians as of September 2021 making Indians the largest foreign group working in UK.

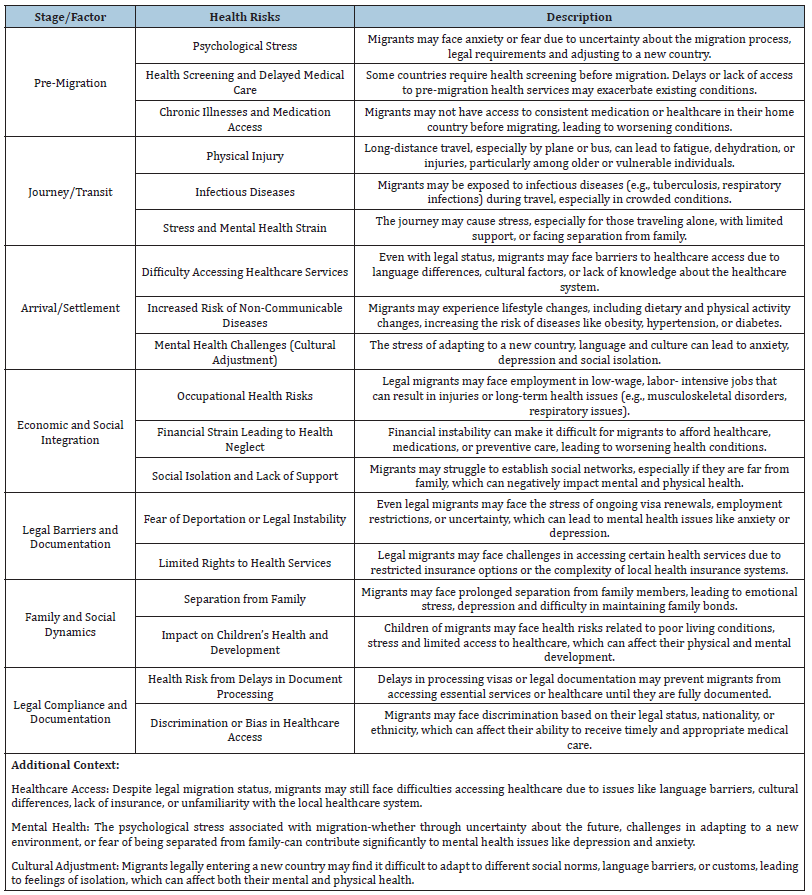

Asian migrants often experience lower socio-economic status, with limited access to stable employment, education and housing. These conditions can lead to poor health outcomes, including higher rates of chronic diseases like diabetes, hypertension and obesity. Poor living conditions, such as overcrowded housing and limited access to clean water and sanitation, further exacerbate these health risks. The interplay of income, employment and housing stability is crucial to understanding the health vulnerabilities in this group. While legal migration provides more opportunities for safety and stability than irregular migration, migrants still face significant health risks. These risks include challenges in accessing healthcare, adapting to new environments, dealing with mental health stress and facing economic insecurity (Table1). Addressing these risks requires targeted support, including healthcare access, mental health services and social integration programs. Access to healthcare is one of the most critical issues for Asian migrants. Language barriers, unfamiliarity with the healthcare system and financial constraints are major obstacles. Migrants may also face discrimination or fear of deportation, particularly those without legal status, which can deter them from seeking necessary medical care. Cultural differences in health beliefs and practices may also hinder effective communication between healthcare providers and migrant patients. Legal status significantly impacts the health of Asian migrants. Undocumented migrants are less likely to have access to health insurance.

Table 1:Vulnerabilities of Legal Migration

The illegal migrants are still at higher risks with psychological and medical health issues, The psychological impact of migration is often underreported. Migrants from Asian countries may experience stress, anxiety and depression due to displacement, cultural adjustment and isolation. The stigma surrounding mental health in some Asian cultures can prevent individuals from seeking help, further complicating the management of mental health disorders. The acculturation process, coupled with the stress of navigating a new society, can add to the stress migration may involve. Migrant populations are particularly vulnerable to infectious diseases, including tuberculosis, hepatitis and HIV/AIDS. These conditions are often linked to migration status, overcrowded living conditions and inadequate healthcare access. The prevalence of such diseases in both the home and host countries contributes to an elevated risk for Asian migrants. Health systems in host countries may lack the resources or knowledge to effectively address these diseases in migrant populations. Keralites belonging to a southern state of India comprise a significant percentage of Asian migrants, particularly due to the recent relaxation of visa rules. Kerala, the southernmost state of India, is known for its high literacy rates, making it one of the most educated regions in the country. Education plays a vital role in shaping the aspirations of children, fostering ambitions for better employment opportunities and improved living standards. This cultural emphasis on education and upward mobility contributes significantly to the trend of migration, with many Keralites seeking employment abroad [1]. In recent years, there has been a marked increase in the number of Keralites migrating to the UK. The UK, with its relatively easy visa policies and employment opportunities in healthcare, IT and other sectors, has become a preferred destination for migrants from Kerala [2]. However, Keralites planning migration should be aware of potential health risks associated with this process. Migration often involves changes in lifestyle, access to healthcare and exposure to new environmental factors, which can affect both physical and mental health [3].

Cardiovascular risks

Deaths due to heart disease are most common in the Northwest of the UK and increase during the cold winter season. Research indicates that colder temperatures exacerbate cardiovascular events due to the constriction of peripheral circulation, which increases the pumping load on the heart, a mechanism believed to contribute to the higher incidence of cardiovascular accidents in colder climates [4]. The mortality rate in Tameside and Glossop (Northwest of England) is almost four times that of Kensington and Chelsea in London. This regional disparity in mortality rates has been attributed to several factors, including socioeconomic conditions, lifestyle and environmental influences [5]. The incidence of heart disease may be even higher among South Indian migrants, particularly those from Kerala, as the cold weather in the Northwest of England could be a contributing factor. South India, being closer to the equator, has a warmer climate and the vascular system of South Indian migrants may not be adapted to the extreme cold [6]. In contrast, North Indians, who are more accustomed to colder winters, may be better equipped to handle the frigid temperatures, potentially reducing their risk of cold-induced cardiovascular events. People living in deprived communities are at greater risk of developing heart disease due to various risk factors such as poor diet, lack of exercise and limited access to health education and advice. Health inequalities are widely documented across the UK, with research highlighting that residents in more deprived areas experience higher rates of heart disease [7]. Geographical and racial health inequalities contribute to the regional variation in the incidence of heart disease. These disparities can be further influenced by cultural factors, including dietary habits and lifestyle choices, which vary across ethnic groups [8]. Kerala migrants may experience additional stress and dietary issues upon migration. Over-nutrition, sometimes due to a lack of knowledge about local dietary habits and food options, is common among migrants in the initial months [9]. The first six months of migration are often challenging for many migrants and they require intensive guidance and support, particularly in terms of adjusting to new dietary and health habits. Support programs that address these issues can significantly improve health outcomes during the adaptation period [10].

Three of the five worst death rates from coronary heart disease are found in the Northwest, while the South has the lowest rates of deaths through coronary heart disease. Among the areas with the highest deaths from coronary heart disease are Blackburn, Leicester City and Manchester [11]. Some of the lowest rates of death through heart disease are found in Westminster, East Sussex Downs and Weald, Dorset and Surrey [12]. Heart UK chief executive Jules Payne opined that no matter where people lived, they could reduce their risk of having a heart attack or stroke by being aware of the risk factors. “There are simple changes that people can make to improve their heart health. Those diagnosed with heart problems should take a proactive approach towards their healthknowing their cholesterol and blood pressure numbers and weight, going for regular check-ups and speaking to their doctor if they have any concerns. For those with a family history of heart disease, small changes to diet and lifestyle, for example, can help reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease” [13].

COVID-19 has provided valuable insight into the medical vulnerability factors of migrants from the Asian continent. The finding that the first 10 doctors in the UK to die from COVID-19 were from ethnic minorities [14], along with observational data from the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC), which showed that a third of COVID-19 patients admitted to critical care units were from ethnic minority backgrounds [15], raised significant concerns about the link between ethnicity and COVID-19 in the UK. Later research on the first British patients to contract COVID-19 further confirmed that Black, Asian and minority ethnic individuals were more prone to severe impacts than white British individuals [16].

Cold weather and weakening of immunity

The immune cells of individuals migrating from hotter climates are genetically adapted to function better in warm weather, which may explain why they perform less effectively in colder temperatures. Research suggests that the immune system of individuals from tropical regions, such as those in South Asia, is not optimized for cold weather and may respond more sluggishly to viral infections [17]. This could explain the observed improved immune response among white British individuals, who are adapted to colder climates. In cold weather, immune cells in people from warmer regions may become hypoactive, leading to increased vulnerability to diseases like COVID-19 [18]. While COVID-19 can thrive equally well in both hot and cold weather, the immune systems of Asian populations, including Keralites, may be less resilient during colder months due to their evolutionary adaptation to warmer environments [19]. This insight highlights the need for individuals from warmer climates to take special precautions during colder seasons. This geographical anomaly of COVID-19 could also be elucidated by other mitigating factors. Vitamin D receptors are found on almost all immune cells and they bind to vitamin D networks within the immune system, playing a crucial role in modulating immune responses [20]. Vitamin D helps to balance immune function, influencing both the innate and adaptive immune systems. It has been shown to reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are associated with pulmonary damage caused by acute viral respiratory infections, such as influenza and COVID-19 [21]. Research suggests that individuals with higher melanin levels in their skin, particularly those of Asian descent, may have lower vitamin D absorption, as melanin reduces the skin’s ability to synthesize vitamin D from sunlight [22]. This physiological factor puts Asian communities at an increased risk of vitamin D deficiency, which contributed to poorer outcomes in conditions like COVID-19 pandemic [23].

Vitamin D deficiency

Prolonged exposure to sunlight is required to accumulate the equivalent quantity of vitamin D produced in individuals with lighter skin. This issue is further intensified in colder countries with limited sunlight, such as the UK, where individuals spend more time indoors and have fewer opportunities to absorb vitamin D [24,25]. In clinical practice, the suggested daily amount of vitamin D is 400 International Units (IU) for children up to age 12 months and up to age 70, the recommended dose is 600 IU. For individuals over 70 years, the advised dose is 800 [26]. In my view, this vitamin D deficiency could be another contributing factor to the observed high rates of COVID-19 in migrant communities, particularly those from regions with higher melanin levels, which further reduce the skin’s ability to synthesize vitamin D [27]. It is important to note, however, that COVID-19 vaccinations have significantly altered the clinical outcomes of the disease in many populations, which should be considered when evaluating this issue [28]. There are also other confounding environmental factors-such as lifestyle, socioeconomic conditions and weather-that contribute to these disparities, which are more related to extrinsic factors than to intrinsic genetic predispositions [29]. Interestingly, the secondgeneration immigrant population seems less affected by these issues and mixed-race individuals, due to the diversity of their immune cells, appear to be more resilient to the viral pandemic [30].

British Malayali, a UK publication, has reported several premature deaths among Kerala migrants [31]. Many towns and villages in Kerala are being reduced to “ghost towns,” with elderly people living alone [32]. Some of these senior citizens migrate or visit abroad to be with their children and grandchildren, only to face additional health hazards, including those exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic [33]. After the COVID-19 pandemic, return migration has increased, but this return migration primarily consists of retired individuals, further adding to the population of the older generation in Kerala [34]. Awareness of one’s own limitations and predispositions prompts individuals to take measures to reduce health risks, a more prudent approach compared to adopting an “ostrich” policy, which avoids confronting potential [35].

SIRT1 and health conditions

The role of the anti-aging gene Sirtuin 1 may be an important factor that determines chronic diseases, COVID -19 and the mental health of migrant populations around the world. Sirtuin 1 is critical to prevent chronic diseases, mental problems and the severity of COVID-19 illness. Sirutin 1 activators are critical such as vitamin D for Sirtuin 1 function and are possibly important to public health interventions. Migrant population may become cognizant of the importance of Sirtuin 1. Sirtuins are a family of proteins that regulate various cellular processes, including aging, inflammation, DNA repair and metabolism. Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) is one of the most studied members of this family and is often referred to as an “antiaging gene” due to its critical role in maintaining cellular health and preventing age-related diseases [36]. Sirtuins are involved in cellular repair and longevity [37]. SIRT1 plays a significant role in repairing damaged DNA. It activates the repair mechanisms that fix DNA damage caused by environmental stressors like UV radiation, toxins and oxidative stress. By promoting DNA repair, SIRT1 helps maintain cellular integrity, reducing the accumulation of mutations that can lead to aging and age-related diseases, such as cancer [38]. Sirtuins have a key role in regulating metabolism as well [39]. SIRT1 is involved in regulating energy metabolism. It controls the activity of enzymes that manage fat, glucose and energy storage in the body. By enhancing mitochondrial function and increasing the body’s ability to burn fat, SIRT1 helps maintain a healthy metabolism and prevent metabolic disorders such as obesity and type 2 diabetes [40]. Chronic inflammation is a key driver of many age-related diseases, including cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative disorders and diabetes. SIRT1 has anti-inflammatory properties; it inhibits the activity of inflammatory proteins, which helps reduce the risk of chronic diseases associated with aging [41].

SIRT1 is known to enhance the cell’s ability to resist various stressors, such as oxidative stress, which occurs when there is an excess of free radicals in the body. Oxidative stress can damage cells and contribute to aging. By promoting the production of antioxidants and improving cellular defense systems, SIRT1 helps cells survive under stressful conditions, which contributes to longevity [42]. SIRT1 also plays a role in regulating programmed cell death (apoptosis). In healthy conditions, it helps prevent premature cell death by maintaining cellular homeostasis. However, when cells become damaged or dysfunctional, SIRT1 can promote apoptosis, removing damaged cells before they can accumulate and contribute to diseases like cancer [43]. SIRT1 has a role in immune system regulation. It helps balance the immune response, preventing excessive inflammation or immune suppression. This is particularly important in aging, as the immune system tends to weaken over time, leading to an increased risk of infections and chronic conditions [44]. SIRT1 is often associated with the concept of longevity because it has been shown in various studies to extend the lifespan of organisms like yeast, worms and mice. In humans, maintaining optimal levels of SIRT1 is believed to help delay One of the most potent activators of SIRT1 is caloric restriction, a wellknown method for extending lifespan in various organisms. Caloric restriction promotes the activation of SIRT1, which in turn enhances cellular repair, metabolism and stress resistance. This is why SIRT1 has become a key focus in aging research, as scientists explore ways to activate it without the need for drastic caloric restriction [45].

SIRT1 is linked to the prevention of various chronic diseases like heart disease, diabetes and neurodegenerative disorders (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease). By regulating inflammation, metabolism and cellular repair, SIRT1 helps protect the body from damage that leads to these conditions [46]. Some research suggests that Sirtuin 1 may play a role in moderating the severity of infections like COVID-19. SIRT1 has been shown to enhance immune response and reduce inflammation, which can be critical in managing the severe inflammatory reactions seen in COVID-19 patients. Defects in the function of SIRT1 could potentially increase the risk of severe disease [47]. There is evidence that SIRT1 is involved in mental health and neuroprotection. It may help prevent neurodegenerative diseases by protecting brain cells from stress and damage. Additionally, SIRT1 is involved in regulating mood and emotional behavior, potentially offering therapeutic benefits for mental health conditions like depression and anxiety [48].

Certain substances have been identified as SIRT1 activators. Resveratrol, found in red wine and certain fruits, is a well-known natural compound that can activate SIRT1 and has been studied for its potential to promote longevity [49]. Nicotinamide riboside and Nicotinamide mononucleotide are precursors to NAD+ (Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide), a molecule required for SIRT1 activity. It has been suggested that vitamin D can enhance the activity of SIRT1, potentially contributing to better immune function and lower inflammation [50]. By activating SIRT1, these substances may help improve health outcomes related to aging, chronic disease prevention and immune function. Sirtuin 1 is a critical gene that plays a central role in aging, chronic diseases and overall health maintenance. Its ability to regulate cellular processes like metabolism, DNA repair and inflammation makes it a key player in preventing age-related diseases and potentially extending lifespan. Ongoing research continues to explore ways to harness SIRT1 activators as therapeutic tools for improving health, particularly for aging populations and individuals at risk of chronic illnesses [51].

Genomics plays a key role in identifying genetic pathways that help treat chronic diseases by delaying programmed cell death. Nutritional interventions, especially very low-carb diets early in life, support the brain-liver connection, while unhealthy diets in aging can disrupt this, leading to liver disease, metabolic disorders and neurodegeneration [52]. Lifestyle changes, particularly low-calorie diets that upregulate SIRT1, promote anti-aging, enhance miRNA function and improve nuclear receptor signaling, may help reverse chronic diseases and prevent autoimmune conditions, potentially preventing Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS) [53].

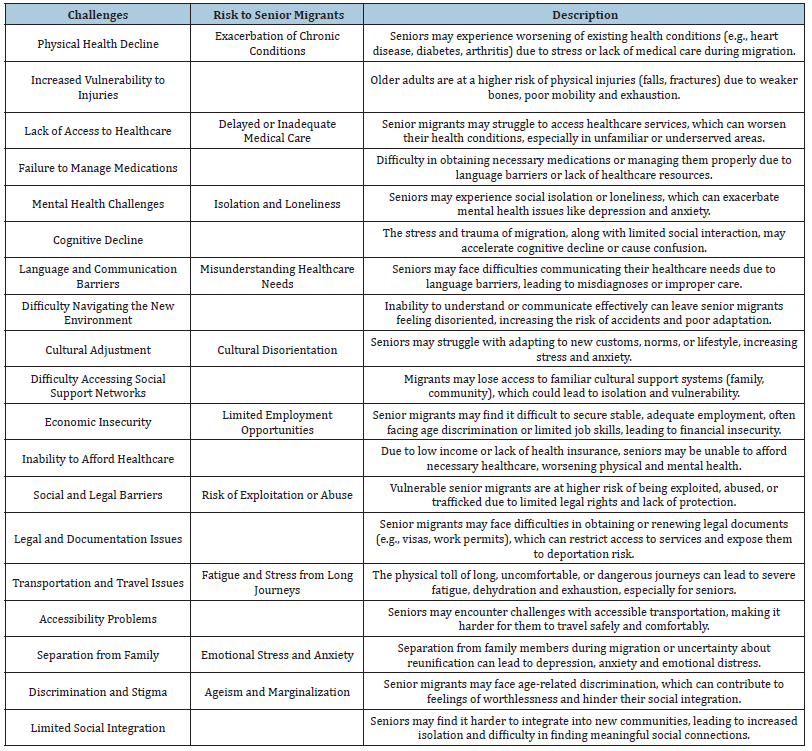

Senior migrants: challenges and additional problems

Chronic diseases are increasingly prevalent in Asian migrant populations, particularly among older migrants. Many come from countries with limited healthcare infrastructure, where prevention and early detection of chronic diseases may be inadequate. Furthermore, the aging migrant population faces additional barriers to healthcare, including language difficulties and lack of culturally competent care. The cumulative effect of aging and chronic disease may increase the overall health burden on both individuals and healthcare systems (Table 2). The global phenomenon of migration has led to significant demographic shifts, with millions of people crossing borders in search of better economic opportunities, safety and a higher quality of [54]. Among these migrants are a growing number of elderly individuals who, either independently or as part of family reunification efforts, are settling in new countries. The aging of elderly migrants presents a unique set of challenges, both for the individuals involved and for the societies that receive them. This essay will explore the multifaceted issues faced by elderly migrants, including social isolation, healthcare access, legal and economic barriers and the psychological and emotional impacts of migration in later life. One of the most pressing issues for elderly migrants is social isolation. Unlike younger migrants who often have more flexibility in integrating into the workforce and local communities, elderly individuals may struggle to build new social networks. Language barriers, cultural differences and unfamiliarity with local customs can prevent older migrants from forming meaningful connections with their neighbors or participating in community life [55]. Additionally, elderly people may experience a sense of disconnection from their country of origin, particularly if they were already living apart from their family members before [56].

Table 2:Additional problems of Senior Citizens.

Social isolation can exacerbate a variety of mental and physical health problems, leading to depression, anxiety and a decline in overall well-being). Without the emotional support of a close-knit community, elderly migrants may feel more vulnerable to economic hardship or physical illness. Furthermore, when elderly migrants are unable to communicate effectively with others or access local services, their sense of alienation intensifies, which can affect their quality of life and overall happiness in their new home. Access to healthcare is another critical issue for elderly migrants, who often face additional barriers when trying to obtain necessary medical services. These barriers include lack of insurance, unfamiliarity with the healthcare system, language difficulties and legal status issues [57]. In many cases, elderly migrants may not be eligible for government-funded healthcare programs in their host country, particularly if they arrived under temporary or irregular immigration statuses [58]. Even if they have legal status, navigating a new healthcare system-especially if it operates on a different model from what they are used to-can be overwhelming.

The medical needs of elderly people are generally more complex, as they often suffer from chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, arthritis, or heart disease. Migrants may not have access to appropriate care for these conditions due to a lack of resources or cultural differences in medical practices [59]. Furthermore, the stress and uncertainty of migration can exacerbate pre-existing health conditions, leading to a decline in physical and mental health. In countries with large migrant populations, the challenge of providing healthcare to elderly migrants becomes even more pronounced. Health services may be overwhelmed by the demand from a growing and diverse demographic and specialized services for elderly migrants are often underfunded or unavailable. This creates a situation where elderly migrants are disproportionately affected by poor health outcomes, including limited access to preventive care, poor treatment adherence and worse prognoses for chronic [60]. Legal and economic barriers are another set of challenges that disproportionately affect elderly migrants. Older individuals, particularly those who are not highly educated or who lack transferable skills, may have difficulty finding stable employment upon arrival. Without a reliable source of income, elderly migrants may experience poverty, which in turn can impact their ability to access housing, healthcare and social services [61]. Even those who have family support may find themselves financially dependent on their children or relatives, which can strain intergenerational relationships [62]. Many elderly migrants face difficulties in securing long-term residency or citizenship, especially if they are migrants without formal documentation or if their legal status is uncertain. In such cases, elderly individuals may live in a constant state of insecurity, fearing deportation or exclusion from essential social services [63]. This lack of legal protection can make it harder for them to access the rights and benefits they would be entitled to in their new country, including healthcare, pensions and social assistance programs. This uncertainty contributes to psychological stress and increases the vulnerability of elderly migrants.

Migration in later life can have significant psychological and emotional consequences for elderly individuals. For many, the decision to migrate is not one made from choice, but rather out of necessity, whether it is to join family members in another country or to escape political instability, economic hardship, or violence [56]. In such cases, elderly migrants may experience feelings of grief and loss, especially if they have left behind a well-established life or the ability to care for their personal needs in their home country [64]. The uprooting of one’s life at an advanced age can also lead to identity confusion and cultural dislocation. Older individuals may struggle with the sense that they no longer fit in with the new culture, while also feeling detached from the country of their origin [65,66]. This dual sense of alienation can lead to a loss of self-esteem and a sense of powerlessness. Moreover, elderly migrants who have been separated from their families or who experience a lack of intergenerational communication may suffer from loneliness and emotional distress, further intensifying mental health issues such as depression and [64]. Additionally, the caregiving needs of elderly migrants can be particularly complicated. In many cultures, it is common for adult children to provide support for aging parents. However, when children migrate to other countries in search of better opportunities, the elderly may be left behind without adequate care, or the children may not be able to offer regular emotional or physical support due to their own financial or legal difficulties in the host country [56].

Summary

Migration is a complex, multifaceted phenomenon that can lead to profound changes in the health and well-being of individuals. Asian migrants, a rapidly growing demographic globally, face a range of health challenges influenced by factors both pre-existing in their home countries and emerging in their new environments. These health vulnerabilities are often underrepresented in public health research and policy, contributing to disparities in health outcomes. This paper examines the key factors that influence the health of Asian migrant populations and suggests strategies to address these challenges. The migration of young people from Kerala to the UK has been driven by dissatisfaction with the local employment system and a desire for better job opportunities. Kerala’s high literacy rate and cultural emphasis on education contribute to the state’s significant outflow of migrants, particularly to the UK, where Indians are the largest group of non-EU immigrants. Many Keralites seek employment in healthcare and other sectors, contributing significantly to the UK economy. However, migration can expose individuals to health risks, particularly in the context of environmental changes, lifestyle adjustments and increased vulnerability to diseases. One notable health concern for Kerala migrants, especially in the colder regions of the UK, is the higher incidence of cardiovascular disease. Research shows that cold temperatures exacerbate heart-related issues, with a higher mortality rate from heart disease in colder areas like the Northwest of England. Migrants from warmer climates, such as Kerala, may be particularly susceptible due to their vascular systems being less adapted to the cold. Lifestyle changes and dietary adjustments during the migration period can also contribute to health challenges, especially in the first few months.

Another significant health risk for South Asian migrants is a weakened immune system in colder weather. Migrants from tropical climates may face immune system challenges in the UK, where their immune cells, adapted to warmer temperatures, perform less effectively in the cold. Additionally, vitamin D deficiency, common in migrants due to limited sunlight exposure in colder countries, may exacerbate health issues, including a higher susceptibility to respiratory infections like COVID-19. Research suggests that people with darker skin, common among South Asians, are at higher risk for vitamin D deficiency, which can further increase vulnerability to conditions such as COVID-19. Despite these challenges, the health risks associated with migration can be mitigated by proactive health management, including dietary adjustments, regular checkups and awareness of the impact of environmental factors. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the additional vulnerabilities of migrant populations, with ethnic minorities suffering more severe impacts. Additionally, return migration after the pandemic has led to an aging population in Kerala, raising concerns about the health of elderly returnees. Overall, the migration process, while offering economic opportunities, comes with significant health risks that require awareness, adaptation and support to ensure migrants’ well-being. The aging of elderly migrants is a growing global issue that requires careful attention from policymakers, healthcare providers and community leaders. These individuals face a unique set of challenges, including social isolation, healthcare access difficulties, legal and economic barriers and psychological stress. Addressing these challenges requires an integrated approach that includes providing adequate healthcare, ensuring legal protections, supporting social integration and offering targeted services to meet the needs of elderly migrants. By recognizing the vulnerabilities of elderly migrants and taking steps to alleviate their difficulties, societies can better support this demographic and ensure that the aging process is one of dignity and well-being, regardless of geographic or cultural background.

As the world continues to experience demographic changes and migration flows, it is crucial to create inclusive policies and community structures that enable elderly migrants to thrive in their new environments, promoting not just their physical health but also their emotional and social well-being. Migrants in general, face a complex set of health vulnerabilities shaped by socio-economic, cultural and policy-related factors. Addressing these challenges requires a multi-faceted approach, including improving healthcare access, increasing cultural competence among healthcare providers and implementing policies that reduce barriers to care. Ultimately, a more inclusive healthcare system, responsive to the specific needs of migrant populations, is key to improving the health and well-being of migrants globally. Further research into this underexplored area is essential to developing effective, evidencebased interventions that can mitigate health disparities and promote equity in healthcare for all.

References

- Govind R (2020) Education and migration: Trends from Kerala. Indian Journal of Migration Studies 34(2): 114-127.

- Kumar A (2021) Keralites abroad: Patterns of migration to the UK. Journal of South Asian Studies 45(1): 56-73.

- Patel R, Thomas G (2019) Health implications of migration: A study of Indian migrants in the UK. International Journal of Health Migration 12(4): 77-89.

- Bhatia P, Singh A, Sharma V (2018) Cold weather and cardiovascular disease: Mechanisms and epidemiological trends. Journal of Cardiovascular Research 29(4): 223-230.

- Mann A, Smith M, Langley J (2019) Regional health inequalities and cardiovascular mortality in the UK. British Journal of Public Health 40(5): 765-772.

- Reddy K, Sharma A (2020) Climate adaptation and its effects on cardiovascular health among South Asian migrants in the UK. Journal of Environmental Health 35(1): 44-51.

- Wilkins R, Johnson R, Patel A (2021) Deprivation and cardiovascular disease in the UK: A geographic and socioeconomic analysis. Public Health Review 51(3): 209-216.

- Smith G, Elvidge S, Clark M (2017) Racial and geographic health disparities in the UK: The case of heart disease. International Journal of Public Health 62(1): 98-107.

- Chakrabarti S, George C (2019) Health Challenges of Migrants: A Case Study of South Indians in the UK. Migration and Health Journal 15(2): 78-85.

- Patel R, Rajan M, Nair S (2020) Adjusting to life in the UK: A review of the health challenges faced by Kerala migrants. Journal of Migration and Health 22(3): 112-118.

- Public Health England (2022) Coronary heart disease mortality statistics: Regional breakdown. Retrieved from gov UK.

- NHS Digital (2023) Cardiovascular disease mortality rates: England by region. Retrieved from NHS Digital.

- Payne J (2024) Interview with heart UK. Heart Health Today Magazine.

- (2020) COVID-19 and Ethnic Minority Health: An Analysis of Impact on Health Professionals. British Medical Association UK.

- (2020) ICU Admissions and outcomes in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Ethnic disparities. Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC).

- (2020) COVID-19: Understanding the Impact on Ethnic Minorities. Public Health England UK.

- Mikulski M (2021) The influence of climate on immune system functionality in migrant populations. Global Health Review 12(4): 205-218.

- Sahoo M (2021) Cold weather and immune response in south Asian migrants: Implications for public health. Journal of Immunology and Migration 45(2): 134-145.

- Jha (2021) Immune system responses and adaptations in migrant populations from tropical climates. International Journal of Migration and Health 18(3): 97-105.

- Hewison M (2010) Vitamin D and the immune system: New insights and clinical implications. Journal of Endocrinology 207(3): 225-238.

- Prietl B (2013) Vitamin D and immune function: An Overview. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 67(6): 590-599.

- Holick MF (2007) Vitamin D deficiency. New England Journal of Medicine 357(3): 266-281.

- Pandarakalam James Paul (2021) Analysis of an epidemiological anomaly of COVID-19: Transcultural and immunological Psychiatry. Science Repository Clinical Microbiology and Research.

- Bishnoi A (2020) Vitamin D deficiency and its role in COVID-19 Outcomes: A review of current literature. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 78: 108296.

- MacLaughlin JA, Holick MF (1985) Disorders of Vitamin D metabolism. Journal of Clinical Investigation 76(4): 1382-1392.

- Institute of Medicine (2011) Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. National Academies Press.

- Vieth R (2009) Vitamin D toxicity, policy and science. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 24(3): 507-514.

- Fernando PP, Stephen JT, Nicholas K, Judith A, Alejandra G, et al. (2020) Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine 383(27): 2603-2615.

- Chung R (2021) Environmental and Socioeconomic Factors in COVID-19 Outcomes. Journal of Global Health 11: 04008.

- Mouhieddine TH (2021) Resilience of mixed-race individuals to viral pandemics: A study on immune diversity. Frontiers in Immunology 12: 656840.

- British Malayali (2021) Premature deaths among Kerala migrants: A growing concern. Retrieved from britishmalayali.com

- Kumar S (2022) The impact of emigration on rural Kerala: Population aging and economic shifts. Journal of South Asian Studies 43(1): 88-103.

- Chandran D, Thomas J (2021) Health hazards and migration: the case of Kerala’s senior citizens post-covid-19. Indian Journal of Public Health 65(2): 146-150.

- Bose A (2022) Return migration and its implications on Kerala’s aging population. Migration and Development Journal 13(2): 250-264.

- Smith J (2020) Health awareness and risk management: A practical approach for older adults. Journal of Geriatric Health 15(4): 322-331.

- Haigis MC, Sinclair DA (2010) Sirtuins in health and disease. Trends in Cell Biology 20(12): 144-151.

- Santos JH (2010) Role of sirtuins in DNA repair and aging. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 20(4): 380-386.

- Lin SJ (2000) Caloric restriction extends yeast life span by inducing genes related to stress resistance and metabolism. Cell 92(4): 527-538.

- Canto C (2010) Sirtuin 1 is essential for health and longevity. Nature 466(7306): 138-142.

- Haigis MC (2006) Sirtuin 1 and the regulation of inflammation. Nature Medicine 12(9): 1155-1157.

- Finkel T (2005) The regulation of cellular responses to oxidative stress by sirtuins. Nature 434(7022): 16-17.

- Onyango IG (2007) SIRT1 protects cells from stress-induced apoptosis. Cell Death and Differentiation 14(8): 1448-1457.

- Choi JM, Park JH (2018) The role of sirtuins in immune system regulation. Immunology 154(3): 251-260.

- Tissenbaum HA, Guarente L (2001) It’s all in the sirtuins: Aging, metabolism and longevity. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2(7): 387-394.

- Mattson MP (2004) Caloric restriction and intermittent fasting: Two potential diets for successful brain aging. Ageing Research Reviews 3(3): 130-144.

- Yang T (2007) SIRT1 regulates energy metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Nature 450(7170): 227-232.

- Koh HY (2021) Role of SIRT1 in the modulation of immune response in COVID-19. Frontiers in Immunology 12: 750-758.

- Fischer FW (2015) The role of sirtuins in neuroprotection. Trends in Neurosciences 38(5): 254-265.

- Baur JA (2006) Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet. Nature 444(7117): 337-342.

- Yoshino J (2018) Nicotinamide mononucleotide: A potential therapy for age-related diseases. Cell Metabolism 27(3): 432-443.

- Dillin A (2002) Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism. Nature 419(6905): 222-228.

- Martins IJ (2016) Anti-Aging genes improve appetite regulation and reverse cell senescence and apoptosis in global populations. Advances in Aging Research 5: 9-26.

- Martins IJ (2019) Body temperature regulation determines immune reactions and species longevity. Heat Shock Proteins in Neuroscience pp. 29-41.

- United Nations (2019) International Migration Report 2019. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

- Schans D (2016) Social networks and the integration of elderly migrants in Europe. International Journal of Migration Studies 14(3): 29-42.

- López JL (2018) The migrant experience: Health, education and family life. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.

- Rechel B (2013) Migration and health in Europe. World Health Organization.

- King R (2019) The global migration crisis: Challenge to the international system. Springer: London.

- Pottie K (2011) Health care for migrants and refugees in Canada: A public health approach. Canadian Family Physician 57(2): 169-176.

- Luntamo M (2018) Health and migration: The global challenge of migrants' health in the 21st Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- Düvell F (2010) Irregular migration: The political economy of migration control. Palgrave

- Kofman E (2018) Gender and migration: The political economy of migrant women’s work. Palgrave Macmillan.

- O'Neil C (2013) Immigration and legal rights: A global perspective. Policy Press.

- Moro D (2021) Psychosocial effects of migration and aging: The case of older migrants in Europe. European Journal of Public Health 31(5): 981-987.

- Harris J, Vickers T (2019) Migration and identity in Later Life. Routledge.

- Victor CR (2002) The prevalence and impact of loneliness in later life. Ageing & Society 22(1): 19-40.

© 2025 James Paul Pandarakalam. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)