- Submissions

Full Text

Forensic Science & Addiction Research

Intentional Handwriting Modifications. Disguise and Autoforgery

Anna Koziczak*

Kazimierz Wielki University, Poland

*Corresponding author:Anna Koziczak, Kazimierz Wielki University, Department of Law and Economics, Bydgoszcz, Poland

Submission: March 06, 2023;Published: March 15, 2023

ISSN 2578-0042 Volume6 Issue1

Abstract

The purpose of this article is to point out the need to order the inconsistent terminology regarding deliberate handwriting modifications and to discuss the merits of distinguishing autoforgery as a separate mode of action. Frequent use of the name “disguise” for any intentional attempt to alter one’s handwriting to prevent recognition, combined with insights that the disguise is rarely effective, can lead to too hasty judgments and errors in expert practice. It is necessary to sort out the terminology and distinguish autoforgery as a special, often difficult to detect mode of action. This article identifies main types of deliberate changes in handwriting according to the criterion of the writer’s purpose and not according to the criteria of the methods used by that person, as it has been done so far. The distinction of autoforgery as a special kind of disguise provides the necessary basis and starting point for experimental statistical research.

Keywords:Handwriting identification; Disguised handwriting; Autoforgery; self-forgery

Introduction

The nature of handwriting is such that, unlike many other forensic traces, it is modifiable: it can be deliberately changed-for example, to imitate someone else’s signature or handwriting or to make it challenging to identify the writer. The first type of activity is usually called forgery; the second type of action is most often referred to as disguise, but literature also includes the terms “autoforgery” [1], “self-forgery” [2], “self-disguise” [3], and others. The terminology regarding intentional modifications to handwriting is inconsistent and unordered. However, three key positions can be observed in the literature. Supporters of the first of them identify disguise as any intentional modification introduced to avoid handwriting identification (“disguised writing is any deliberate attempt to alter one’s handwriting to prevent recognition” - Koppenhaver [3]. Several other authors share this approach in their works [4-6].

Proponents of the second position find the term “disguise” too capacious and, therefore, try to introduce additional terms to describe intentional modifications of handwriting in a more precise way. For example, Pfanne [7] divides disguise into two types: “narrow disguise” (masking) and “any distortion of handwriting”. Based on medical terminology, Franck [8] introduces two other categories of disguise: “chronic” and “acute”. Ellen [9] distinguishes self-forgery as a particular type of signature disguise, noting that the methods of self-forgery activities vary, depending on whether the signature is to be subject to standard, routine benchmarking or not. According to Ellen [9], the main goal of the individual is to deny the authenticity of the signature later. However, he uses the term self-forgery in quotation marks, which may indicate some disbelief in this term.

Proponents of the third position also seem to find the term disguise insufficient to describe reality. They note the existence of a particular variety of disguise but consider the use of the terms self-forgery and autoforgery as incorrect. For example, Huber and Headrick [10] define autoforgery as “a forgery of one’s signature created by oneself”. They state that forgery by definition means an execution performed by another person, which must lead to the conclusion that something like autoforgery does not exist. A similar argument was previously made by Michel [11], who considered describing deliberate alterations to one’s signature by the term autoforgery to be “unfortunate”. He argued that, according to common language usage, forgery refers to the fraudulent intent of imitating an object; meanwhile, the doer, by distorting his/her signature, does not create a non-authentic signature. In addition to the three most common options mentioned, there is also a different understanding of basic terms in the literature. For example, Harrison [12] uses the term disguise to cover any “deliberate departure from normal handwriting habits”, including careful copying of someone else’s authentic signature. In turn, some authors, when writing about autoforgery, mean only modifications made in a situation where a person intending to deny the authenticity of the signature in the future must write it under control of the recipient, who can directly compare it with the specimen signature [13].

Lack of proper ordering of terminology regarding intentional handwriting changes can lead to confusion and more severe effects than just disputes in literature. An example of such a situation, which the author encountered in practice, is a handwriting expert opinion in which the expert described the questioned signature on the bill of exchange as an “inauthentic signature”. This led to an unjust accusation of the obligee, who was seeking the claim from the bill of exchange, for counterfeiting the document. During the subsequent hearing before the court, the expert explained that when writing about the “non-authentic signature” he meant a signature deviating from the specimen signature generally used by the person concerned. The reason for the misunderstanding was that the signature on the bill of exchange was illegible, and its writer most often used a legible signature. Regardless of the issue of terminology, in the author’s opinion, the recognition of autoforgery (no matter what it might ultimately be called) as a particular type of disguise is both advisable and necessary because the nature of the activities now commonly called disguise can vary greatly. The fundamental difference between disparate types of disguise comes down to the purpose with which the person writing takes action. This objective determines, among others, writing methods, scope and direction of modification, and their effectiveness, which translates into the possibility of detecting disguising actions. Assuming the criterion of the goal of activities, disguise can be divided into two basic types.

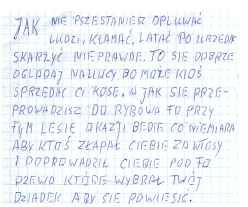

In some cases, the primary purpose of the writer is only to prevent him/her from being identified as the performer

For example, when writing an anonymous letter. By setting such a goal, the author of the handwriting can even afford the obvious unnaturalness of his/her writing, because it is irrelevant to him/ her. It is only essential that it is impossible to determine his/her performance. So, for example, he/she can use a template (Figure 1) or create letters only from simple, unbound lines (Figure 2). Such actions can be called depersonalisation of handwriting, “masking”, or, as Pfanne wrote, “narrow disguise”. Slightly simplified, it can be stated that the person who undertakes such activities adopts the assumption that “you will not prove to me that I have written it”. Where the purpose of the writer is depersonalisation, the mere statement of the unnatural character of handwriting does not pose the slightest difficulty. The ability to identify the writer depends on his/her skills and ingenuity, and above all on the adopted method of changing graphism. Some depersonalisation methods, such as using a template, actually minimise the likelihood of introducing the writer’s own characteristics to handwriting, and thus the ability to identify it. In general, however (e.g., when the method used by the writer boils down to a change in the type of writing), the writer’s efforts are not very effective. People trying to depersonalise their handwriting significantly overestimate the effectiveness of the conspicuous-but from the expert point of viewminor changes in the scope of the “picture effect” of writing. Tests of a suitable quantity and quality of comparative material (standards of comparison) typically detect such operations. Cases of effective depersonalisation are, therefore, not very common in practice.

Figure 1: Masked handwriting using a template - devoid of features that allow identification of the writer.

Figure 2:A typical example of a failed masking (depersonalisation) of writing. Contrary to popular belief, the use of print-like handwriting, simplified character design, and low impulse usually do not prevent identification of the writer.

Sometimes the writer’s goal is not only to prevent his/her identification as a doer but also to create the impression that this doer is some undefined third party

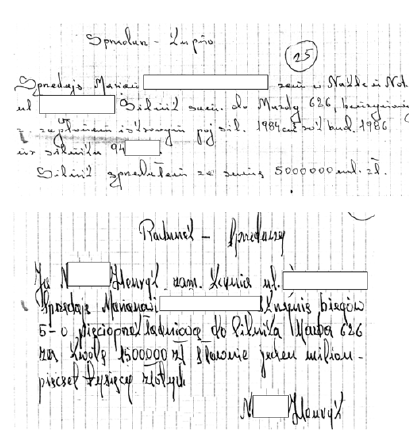

This is the case, for example, when a person modifies his/her signature on a check to later deny its authenticity and claim that the money from his/her account has been paid to someone else. In such cases, if the signature is to be accepted by the recipient, it should be drawn fairly freely and look natural. Whether this intended effect can be achieved depends on a number of factors, not only related to the writer him/herself (his/her knowledge, abilities, ingenuity), but also the object of his/her activities (the size of the sample and the degree of its saturation with characteristic features), and even factors related to the “recipient” of the handwriting. Whatever the final result, we are dealing with an action that can be called pseudo-personalisation. Such activities are sometimes referred to in the literature as autoforgery or self-forgery. The person who undertakes them strives to convince the environment that “I was not the one who wrote, someone else did it”. These activities usually concern signatures, but handwriting can also become an object of autoforgery. This is the case, for example, when a person making a signature autoforgery is forced to write some additional entries next to it, e.g. the date or annotations, such as “I confirm the receipt of documents” or “I guarantee this promissory note”. Placing both the signature and handwriting under autoforgery is a necessity in such cases because lack of consistency would expose the writer to the risk of being easily identified. Documents that are particularly vulnerable to autoforgery include bills, invoices, documents confirming the receipt of cash or merchandise, all kinds of contracts, bills of exchange, as well as request writing for expert analysis.

Of course, with pseudo-personalisation of the signature, the writer faces other requirements, when the recipient does not know what the authentic signature looks like, and different when he/she knows a specimen signature. In the first case, intentional modifications may include any graphic features, as long as the change in features does not cause the unnatural appearance of handwriting and as long as, at least according to the doer’s assessment, the change is sufficiently significant to prevent his/her identification (“free-form disguise strategy”). The second situation gives the writer far fewer opportunities to act because modifications that will enable him/her to deny the authenticity of the signature in the future cannot be serious enough to arouse the suspicion of the recipient (e.g., a bank employee). It is also different when the writer can practice the modifications him/herself and differently when he/ she is forced to modify his/her ad hoc writing. Different conditions for autoforgery not only mean a different degree of difficulty for the writer but also entail differences in the ability of the expert to detect deliberate modifications. The latter largely depend on the size of the samples tested. If pseudo-personalisation concerns a longer text, identifying the performer usually does not pose any significant difficulties. Avoiding the involuntary introduction of the writer’s own features into a deliberately changed handwriting is very difficult; the more difficult, the longer the prepared sample (Figure 3). There are, however, exceptions to this rule, especially if the writer is able to use several “handwriting styles” with equal skill [14]. In such cases, handwriting samples drawn by one person can vary significantly in graphism; this phenomenon has been described as “multi-individuality of writing” [15]. There is then a risk that the inexperienced expert, who does not discern in any of the examined samples signs of unnatural hand, will recognise them as coming from different people.

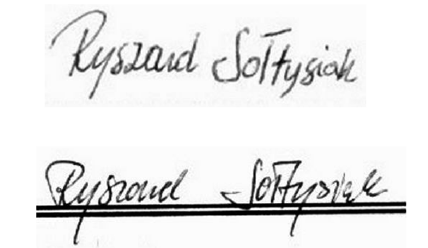

Figure 3:Two contracts drawn up by the same professional forger of documents, without clear signs of unnaturality, and at first glance they differ in graphism from each other.

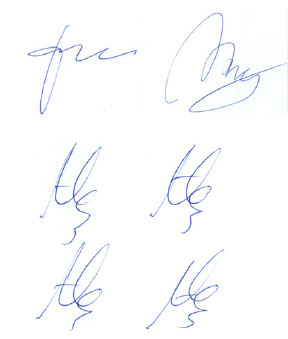

If changes in graphism have been introduced into small, multiletter graphics, e.g., signatures, identification of the performer is much more complicated and sometimes even impossible. In other words, along with the shortening of a deliberately modified sample, the chance decreases not only to indicate the actual doer but also to conclude that its graphic features are not natural, i.e., that they differ from those developed and fixed by habit (Figure 4). With regard to initials with a straightforward structure (Figure 5), the formulation by the expert of any categorical conclusions may involve high risk.

Figure 4:Completely different graphic features of two “signatures” invented and outlined ad hoc (top) and natural signatures of the same person (bottom).

Figure 5:The most simplified form of the initial may prevent both validation and exclusion of its authenticity.

A separate type of intentional modification of one’s writing are actions intended to create the appearance that handwriting-e.g., a signature on a contract or will comes from a specific third party in order to misidentify the performer. Such activities are commonly referred to as forgery, and this term does not cause controversy. The forger makes alter-personalisation: he/she changes the graphism of his/her writing, but of course, changes cannot go in any direction. The intentionally modified writing must be characterised by graphism maximally coinciding with the graphism of the imitated specimen (Figure 6). It should look natural, and more precisely it should not deviate from the imitated standard. This reservation is vital in cases where the specimen comes from, e.g. an elderly and sick person, and therefore contains signs of so-called unintentional unnaturalness. Then the writing of the person making the forgery should contain similar signs of unnaturality, but it will be intentional unnaturality. Also in this case, the person’s purpose implies methods that can be used for forgery. For the most part, they are not the same methods of operation that are used for autoforgery or disguise of handwriting. A more detailed discussion of forgery is beyond the scope of this work. The techniques used by individuals to modify their writing can be very different. Which one will be used in a particular case depends primarily on the main purpose of the writer’s actions. The final effect of the practical implementation of these changes largely depends on the individual abilities of the writer, and his/her skills and training options. A small proportion of people, when writing, can easily and smoothly change their graphism Harrison [12] without any technical procedures or any visible signs of unnaturalness, being able to change any or specific handwriting features depending on their needs.

However, most writers can intentionally change only a few

features of their writing for example:

A. type (from “regular” to “in a print-like pattern”),

B. pace, impulse (usually from higher to lower) or

C. slope (from right-oblique to left-oblique or vice versa).

Figure 6:Example of forgery (alter-personalisation) of the signature; top - a forged signature, bottom - an authentic signature. Because the signature is long, the forger failed to reach either sufficient convergence with the pattern features or avoid signs of unnatural hand.

The interdependence of the graphic attributes of writing means

that often making a deliberate change of one feature results in an

unintentional but usually beneficial from the writer’s point of

view – change in several other features. Regardless, most people’s

writing habits are strong enough that they need to use specific

writing techniques to change more features. These techniques

include the following:

A. for masking (depersonalisation)-e.g., writing with a

template or writing “on a ruler”,

B. for autoforgery (pseudo-personalisation) – e.g., writing

in an unusual position, on a movable pad, or on an unusually

arranged sheet of paper.

C. in the case of forgery (alter-personalisation) – copying,

e.g., through a glass pane or tracing paper.

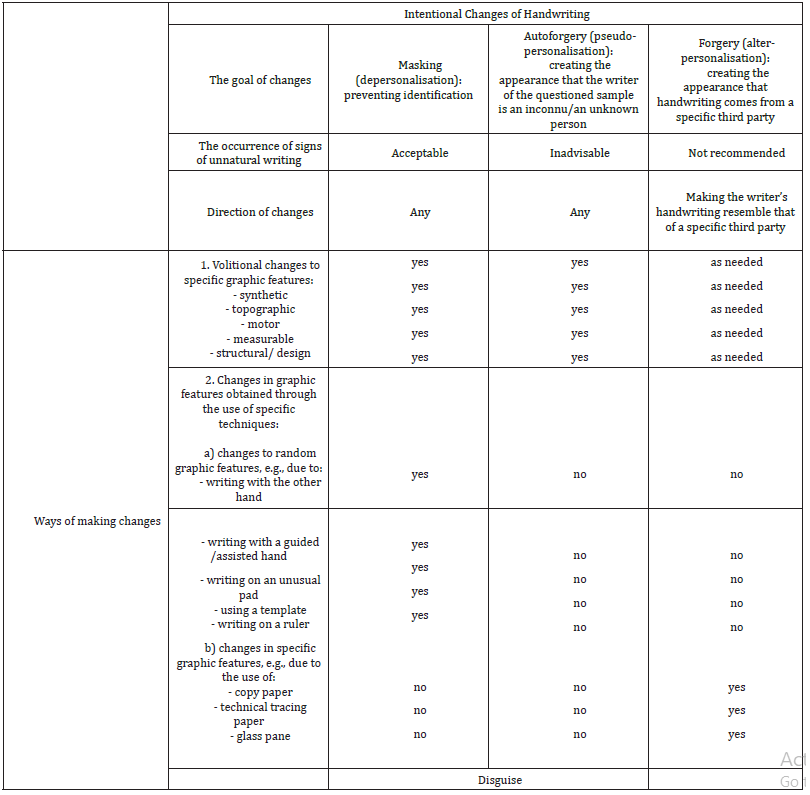

A summary of the above remarks can be seen in Table 1. It presents the similarities and differences between masking (disguise sensu stricto) and autoforgery in combination with the third type of intentional handwriting changes, i.e., forgery. As can be seen from the table, although both depersonalisation and pseudo-personalisation of writing rely on deliberately modifying its features, which allows to consider them as various forms of disguise, these actions clearly differ from each other. This justifies the need to distinguish autoforgery (under this or another name) as a separate mode of action. The solution to problems arising from the legal implications of the word forgery could be, for example, the replacement of autoforgery with the term “auto-simulation”, proposed in one of the articles Mohammed [13]. The term autoforgery does not affect the author. It may be because, in Polish law, forgery means not only counterfeiting of an object (that is, fraudulently imitating another real one) but also alteration, i.e., an unauthorised introduction of changes to an existing object created by an authorised person or institution. The nature of autoforgery is similar to forgery in the form of alteration.

Table 1:

Distinguishing autoforgery in the group of activities now termed disguise is essential not only for organisational but also for practical reasons. Almost all disguise publications, starting with Osborn’s book more than 100 years ago, state that disguise is rarely logical, consistent, and original, and therefore is infrequently effective [9,16,17]. Authors who write about intentional modifications of illegible signatures note that they often have clear connections with legible signatures of a given person [18], which, of course, makes identification easier. Such statements, although true, can have a calming effect on experts and convince them that all such procedures can be easily detected, which is no longer valid. Although some authors warn that some cases of disguise (autoforgery) can be a big challenge for the expert Harrison [12], practice shows that many experts do not take this to heart, which results in erroneous opinions. The risk of error occurs particularly in examinations of signatures made when the recipient does not have access to the specimen signature. Finding in such a signature neither signs of unnaturality nor significant common features with the standards, some experts too hastily exclude its authenticity. Meanwhile, the author’s years of research into autoforgery shows that the number of exceptions to typical, easy-to-detect cases of autoforgery is higher than one would expect.

These studies also indicate that difficulties in distinguishing between autoforgery and forgery as well as those from changes due to natural causes can occur not only in the case of short, simple signatures but also in the case of larger samples of handwriting. The number of instances of undetected autoforgery that were mistakenly considered to be forgery and ended in the discontinuation of the case due to a failure to identify the perpetrator, or even worse in the accusation of an innocent person of using a false document, may therefore significantly exceed the estimates. The possibility of autoforgery should always be taken into account when the circumstances of the case are such that the writer may be interested in avoiding the legal consequences of signing the document or writing down its content and when the recipient of the document does not know what the authentic signature of a given person looks like. In such cases, special care should be taken in examinations, regardless of whether they relate to short or long records, even if there are no signs of abnormality in the questioned or comparative samples.

References

- Levinson J (2001) Questioned documents. A Lawyer’s Handbook, Academic Press, San Diego, San Francisco, New York, Boston, London, Sydney, Tokyo, Japan.

- Koppenhaver KM (2002) Attorney’s guide to document examination. Quorum Books, Westport-London, UK.

- Koppenhaver KM (2002) Attorney’s guide to document examination. Quorum Books, Westport-London, UK.

- Purdy DC (2006) Identification of handwriting. In: Kelly JS, Lindblom BS, (Eds.), Scientific Examination of Questioned Documents, CRC Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton-London-New York, USA, pp. 47-74.

- Morris R (2000) Forensic Handwriting Identification. Fundamental concepts and principles, Academic Press, San Diego, San Francisco, New York, Boston, London, Sydney, Tokyo, Japan.

- Webb FE (1978) The question of disguise in handwriting. Journal of Forensic Science 23(1): 149-154.

- Pfanne H (1971) Manuscript adjustment, Bouvier Verlag Herbert Grundmann, Bonn, Germany.

- Pfanne H (1971) Manuscript adjustment, Bouvier Verlag Herbert Grundmann, Bonn, Germany.

- Ellen D (1997) The scientific examination of documents. Taylor & Francis, London, UK.

- Huber R, Headrick AM (1999) Handwriting identification: Facts and fundamentals, CRC Press, New York, USA.

- Michel L (1974) Disguising one's own signature. Archives of Criminology 154(1-2): 43-53.

- Harrison WR (1981) Suspect documents. Their Scientific Examination, Nelson-Hall Publishers, Chicago, USA.

- Mohammed LA, Found B, Caligiuri M, Rogers D (2011) The dynamic character of disguise behaviour for text‐based, mixed, and stylised signatures. J Forensic Sci 56(S1): S136-S141.

- Konstantinidis S (1987) Disguised handwriting. Journal of Forensic Science Society 27(6): 383-392.

- Moszczyński J (2019) The multi-individuality of handwriting. Forensic Sci Int 294: e4-e10.

- Osborn AS (1910) Questioned documents. The Lawyers’ Co-operative Publishing CO., Rochester NY, USA.

- Alford E (1970) Disguised handwriting. A statistical survey of how handwriting is most frequently disguised. J Forensic Sci 15(4): 476-488.

- Harris JJ (1953) Disguised handwriting. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 43(5): 685-689.

© 2023 Anna Koziczak. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)