- Submissions

Full Text

Forensic Science & Addiction Research

When Naloxone is Too Little, Too Late by the Numbers

Laura M Labay1*, Jolene J Bierly2, Charles A Catanese3 and Carol M Smith4

1Toxicology, NMS Labs, United States

2Toxicology, NMS Labs, United States

3Pathology, Westchester County Healthcare Corporation, United States

4Department of Health and Mental Health, United States

*Corresponding author: Laura M Labay, NMS Labs, 200 Welsh Road, Horsham, PA, United States

Submission: July 12, 2019;Published: August 22, 2019

ISSN 2578-0042 Volume5 Issue2

Introduction

Naloxone is an antagonist used to temporarily reverse the physiological effects associated with opioid overdose. Nearly every state has enacted legislation that permits pharmacists to distribute the medication without a prescription [1]. This practice provides those in the social or drug-using networks of an at-risk individual to administer naloxone for emergency treatment purposes, when the first signs and symptoms related to an overdose are recognized. Naloxone is touted in the media as a “miracle drug” that saves lives [2,3]. This is true; research demonstrates that when naloxone is available to community members, opioid related deaths decrease in that community [4]. It is important, however, to promote to the general public and public health decision makers that naloxone is not a panacea for drug addiction. Treatment options involve a range of strategies and are associated with variable effectiveness, but in the absence of comprehensive treatment programs, a steadfast social support network, prescription monitoring programs, and long-term clinical support that includes psychiatric care, medication management and substance abuse monitoring, the cycle of overdose and naloxone treatment continues [5-7].

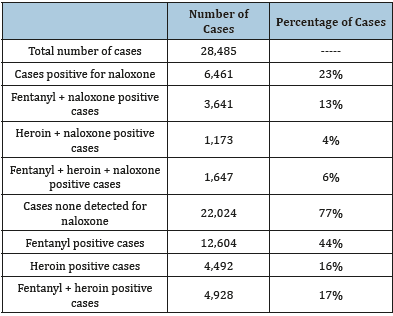

The inadequacy of naloxone as a drug epidemic remedy is all too apparent when postmortem toxicology results and individual case histories are examined. Medical Examiners and Coroners determine cause of death when a death is unnatural, unexpected or occurs under unusual or suspicious circumstances. A thorough medicolegal investigation includes the collection of biological samples for toxicological analysis where the analytical scope is dependent upon case-specific circumstances. NMS Labs is a national reference laboratory that performs toxicology testing for death investigation purposes. From 2017 to 2018, NMS Labs performed testing for 28,485 postmortem cases in blood where heroin, fentanyl, or both were confirmed, and naloxone was included in the scope of analysis. Naloxone was not detected in 77% of the total cases evaluated (Table 1). Potential reasons for the absence of naloxone in these cases are several-fold including unattended or non-witnessed death, the clinical decision that naloxone treatment would not be effective, or naloxone not being readily available when needed. Furthermore, where detailed case history was submitted to the laboratory, examples of emergency personnel or bystanders administering naloxone without successfully reversing opioid effects were identified. For example, in one case, a friend administered naloxone to a 36-year-old male shortly after he became unresponsive. Emergency personnel were contacted, and the individual was transported to the emergency room where he arrived in asystole and was pronounced dead a short time later. Toxicology testing showed the presence of several opioids including heroin, oxycodone, fentanyl, and a fentanyl-analogue in addition to ethanol, mirtazapine, alprazolam and cocaine. In a second case, emergency personnel were contacted for a 49-year-old male after he was observed collapsing at his home. According to the case history, two doses of naloxone were administered in the field with no response. The individual was transported to the hospital where he was pronounced dead shortly after arrival. Toxicology testing showed the presence of heroin, a nicotine metabolite, and a pharmacologically inactive breakdown product of cocaine. In a third case, a 39-year-old male was found unresponsive on the floor of his home. Resuscitation attempts were made with no success; the decedent remained unresponsive and death was pronounced upon arrival at the hospital. Further investigation revealed the individual had been treated for heroin overdoses on two previous occasions in the same month. Toxicology testing showed a combination of cocaine, heroin, and fentanyl.

Table 1:Naloxone in cases from 2017-2018*.

The presented data shows that naloxone reversal failed in 23% of the postmortem cases included in this study and no analytical indications of its use was present in the remaining 77% of cases. Two main reasons exist for lack of drug efficacy across these and other drug-related deaths. First, for naloxone to be effective administration must occur at an appropriate dosing regimen in a timely manner [8]. Illegally purchased drugs may contain harmful contaminants and adulterants or be manufactured with a non-wanted drug at an unknown dose [9,10]. Examples include counterfeit benzodiazepine tablets that contain fentanyl, or heroin surreptitiously mixed with a fentanyl analogue. It is important to recognize from a medical and public health perspective that these analogues and other opioid-related novel psychoactive substances have not been subjected to clinical trial assessments and, as such, their naloxone administration requirements not optimized or disseminated in any formal capacity. Once respiratory depression progresses to prolonged hypoxia and brain function becomes increasingly compromised, reversal without health consequence becomes less likely [11]. Second, not all drug deaths are related to opioid use. Deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants have increased in the United States in recent years; among 70,237 drug overdose deaths in 2017, nearly a third involved cocaine, psychostimulants, or both [12].

It is of pharmacological importance that naloxone via its action as an opiate-receptor antagonist will not be successful in reversal of an overdose precipitated by stimulants such as methamphetamine and cocaine or other depressants such as ethanol, benzodiazepines and antidepressants. In the absence of proper funding at local, state, and federal levels to treat the underlying causes of addiction and to educate opioid users and their care providers, there is minimal expectation that the current drug crisis will abate. In conclusion, while naloxone is an important front-line medication it is not by itself sufficient to correct addiction, halt the initiation of an overdose or relapse, stop the cycle of overdose and reversal, and in some cases prevent death. The numbers speak for themselves. Only cases where heroin, fentanyl, or both were confirmed, and naloxone was included in the scope of testing were included in these statistics. Other drugs may have been present.

References

- (2019) Prescription Drug Abuse Policy System-PDAPS.

- (2019) Naloxone: The life-saving opioid overdose antidote more Americans need-60 minutes-CBS news.

- (2019) The purdue case is one in a wave of opioid lawsuits. What should their outcome be? New York, USA.

- Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, Quinn E, Doe Simkins M, et al. (2013) Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in massachusetts: Interrupted time series analysis. BMJ 346: f174.

- Fink DS, Schleimer JP, Sarvet A, Grover KK, Delcher C, et al. (2018) Association between prescription drug monitoring programs and nonfatal and fatal drug overdoses: A systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine 168(11): 783-790.

- Kampman K, Jarvis M (2015) American society of addiction medicine (ASAM) national practice guideline for the use of medications in the treatment of addiction involving opioid use. Journal of Addiction Medicine 9(5): 358-367.

- Dugosh K, Abraham A, Seymour B, McLoyd K, Chalk M, et al. (2016) A systematic review on the use of psychosocial interventions in conjunction with medications for the treatment of opioid addiction. Journal of Addiction Medicine 10(2): 93-103.

- https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/opioids/how-administer-naloxone

- Arens AM, Vo KT, Lynch KL, Wu AHB, Smollin CG, et al. (2016) Adverse effects from counterfeit alprazolam tablets. JAMA Internal Medicine 176(10): 1554-1555.

- Dowell D, Noonan RK, Houry D (2017) Underlying factors in drug overdose deaths. JAMA 18(23): 2295-2296.

- Kiyatkin EA (2019) Respiratory depression and brain hypoxia induced by opioid drugs: Morphine, oxycodone, heroin, and fentanyl. Neuropharmacology 151: 219-226.

- Kariisa M, Scholl L, Wilson N, Seth P, Hoots B (2019) Drug overdose deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants with abuse potential-United States, 2003-2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 68(17): 388-395.

© 2018 Jesus Laura M Labay. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)