- Submissions

Full Text

Forensic Science & Addiction Research

Gender Differences in Suicide Rates

Mustafa Demir*

Department of Criminal Justice, State University of New York at Plattsburgh, USA

*Corresponding author: Mustafa Demir, Department of Criminal Justice, State University of New York at Plattsburgh, 101 Broad Street, Plattsburgh, NY-12901, USA

Submission: March 01, 2018; Published: March 19, 2018

ISSN: 2578-0042 Volume2 Issue5

Abstract

Objective: There is limited research on the trends in suicide rates by gender in Turkey. The purpose of the study is to examine suicide rates by gender over time and whether suicide rates by gender differ significantly.

Method: The data on suicide from 2007 to 2016 were obtained from the Turkish Statistical Institute. The number of suicide cases was 28,760 (72.5% male, 27.5% female). Direct standardization method was used to calculate gender specific suicide rates. Numerical (correlation) and graphical (line charts) methods were used to reveal the trends in suicide rates by gender. Then, paired-sample t-test was conducted to determine whether suicide rates significantly differed by gender.

Results: The increase in suicide rates among males was not statistically significant while there was a statistically significant decrease in suicide rates among females over time. The ratio of male to female suicide rate increased significantly over time. In addition, the difference in suicide rates between males and females was statistically significant. Male suicide rates were 2.5 times higher than that of female.

Conclusion: Suicide rates differ by gender.

Keywords: Suicide; Gender

Introduction

Suicide is defined as killing oneself deliberately [1-3]. Suicide is a very serious public health problem and one of the top 20 leading causes of death in the world [4]. For instance, in 2015, about 800,000 people ended their lives by committing suicide [5]. It is important to note that the global suicide rate per 100,000 populations is 10.7 [6]. Although the suicide rate in Turkey is about 2.5 times lower than the global suicide rate [7], similar to the other countries, it has been recognized as a public health issue requiring attention. To address this problem, this study focuses on investigating the trend in suicide rates by gender over time in Turkey and whether suicide rates by gender differ significantly.

A number of previous studies conducted in different countries examined gender differences in suicide rates. All of them have found that males commit suicide more than females [8-19]. One study found that the global male to female suicide ratio is about 3.6, which means that males committed suicide about 3.6 times as high as females [8].

The ratio of male to female suicide rates may vary by countries. For instance, the past research found that compared to female suicide rates, the suicide rates for males were higher 5 times in Europe [20], 3.6 times in the US [10], 3 times in the UK [21] and 2.5 times in the Republic of Korea [20]. Similar to the other countries, one study conducted in Turkey found that the average suicide rate between 1987 and 2011 for males was 1.8 higher than that for females [22]. In fact, compared to the other countries, the male to female ratio is lower in Turkey.

Although compared to female suicide rates, the suicide rates for males has remained constantly higher, suicide trends by gender may vary over time. For instance, in the most recent years between 2014 and 2015, in England, female suicide rates increased while male suicide rates decreased since 2014 [21]. However, in Scotland, and the Republic of Ireland, both female and male suicide rates decreased whereas both male and suicide rates increased in Northern Ireland, and Wales between 2014 and 2015 [21]. Similar to the trend in Northern Ireland and Wales, in the US, there was an increasing trend in both male and female suicide rates between 1999 and 2014 [10]. The results of the study conducted in Turkey showed that, between 2002 and 2011, female suicide rate has a decreasing trend since 2003 while male suicide rate increased until 2009 and decreased between 2009 and 2011 [4].

It is important to note that there may be differences in suicide rates by gender across countries. However, there is scant research that investigated suicide rates by gender in depth by using statistical analyses, particularly in Turkey [4,22]. In addition, the studies conducted in Turkey did not use the most recent data on suicide rates by gender over time, and did not test whether suicide rates by gender differed significantly. There might be changes in suicide rates by gender over time, which requires new research. In addition, analysis of the most recent data may help to identify the recent trends in suicide rates in males and females and to develop specific suicide intervention programs [23]. To fill the gap in the literature in the context of Turkey, the present study focused on investigating suicide rates by gender, and the trends in suicide rates in males and females using the most recent data and various statistical analyses. More specifically, the study was designed to address the following research questions and hypotheses:

1. Is there any variation in suicide rates by gender over time?

Hypothesis 1: Suicide rates increase in males while female suicide rates decrease.

2. Does male to female suicide ratio differ significantly over time?

Hypothesis 2: The ratio of male to female suicide rate increases significantly over time.

3. Do suicide rates differ by gender significantly?

Hypothesis 3: Male suicide rates are significantly higher than that of females.

It is important to examine suicide rates between females and males to determine the risky groups. Based on the findings, policy makers may focus on them and take necessary steps to prevent further suicides.

Method

Data

The data on suicide between 2007 and 2015 were extracted from the Turkish Statistical Institute (TUIK) website. TUIK collects official statistics from the other governmental agencies [24]. All suicide or undetermined deaths are referred to medical examiners in Turkey.

Two different data for each year from 2007 to 2016 were extracted from the TUIK website: number of suicide cases by gender [25] and population data by gender [26]. Afterward, the data were combined together for each year based on gender.

Measures

Suicide rates depend on population. Due to difference in population size, only looking at the number of suicides may be misleading as to where suicide is more prevalent [27]. Thus, to control for the effects of population differences in specific groups, direct standardization method was used to calculate gender specific suicide rates for each year [27] . Specifically, gender-specific suicide rate was obtained by dividing the number of suicide cases for each gender group by the corresponding population in that gender group, and then multiplying by 100,000. The above mentioned calculations were made for each year separately. Then, gender specific suicide rates (male and female specific suicide rates) were put side by side per year for the analysis. The level of measurements of the obtained gender specific suicide rate was continuous.

Analytical strategy

Data analysis was performed using Stata 14.2 software. For descriptive analysis, the categorical variables of gender, and for all other analysis, the new created variables on "gender specific suicide rate" (male suicide rate and female suicide rate) were used. The analyses consisted of several stages: First, descriptive statistics about suicide by gender was provided. Second, the Shapiro-Wilk W test was used to test whether the data for each variable was normally distributed. If the results of Shapiro-Wilk W test are statistically significant (p<0.05), then the data are not normally distributed. Normality test is important to determine whether Pearson correlation test is appropriate. Third, Pearson's correlation test between the examined years and the gender specific suicide rates (e.g., correlation between the years and male suicide rate; correlation between the years and female suicide rate) and graphical methods (line charts) were used to reveal the trends in gender specific suicide rate. Finally, paired sample t-test was conducted to determine whether there was a statistically significant difference between male specific suicide rate and female specific suicide rate [28] . In addition, the male-to-female ratio was reported to examine how much difference there was between males and females in terms of suicide rate. Results were classified as significant at a level of p<0.05.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1. The results indicated that 28,760 people committed suicide between 2007 and 2016. The majority of them were males (72.5%).

Table 1: Descriptive statistics.

Note. N=28,760.

Trends in suicide rates by gender

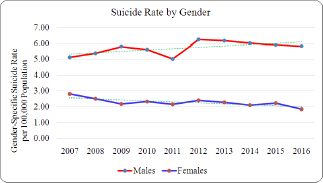

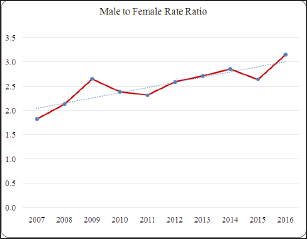

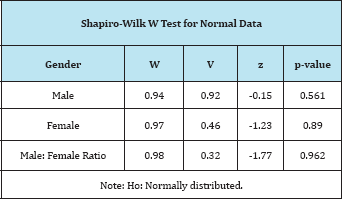

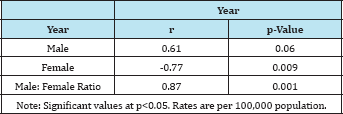

Figure 1 shows the trends in suicide rates by gender and Figure 2 shows the ratio of male to female rate between 2007 and 2016. Table 2 shows the results of the normality test, and Table 3 shows the correlation coefficients of gender specific suicide rates and years.

The results of the normality test showed that male suicide rate, female suicide rate, and the ratio of male to female suicide rate were all normally distributed. Thus, Pearson's correlation (r) was performed to determine the relationship between gender specific suicide rate and years, and between male to female ratio and years.

Figure 1: Trends in suicide rates by gender between 2007 and 2016.

Note: Dot lines show the trend line

Figure 2: Trends in male to female suicide rates ratio between 2007 and 2016.

Note: Dot lines show the trend line. Rates are per 100,000 populations

Table 2: Results of normality test.

Table 3: Correlation coefficients of gender specific suicide rates and years.

During the ten-year period, overall, there was an increase in suicide rates among males and in the ratio of male to female rate whereas suicide rates among females decreased over time. The increase in suicide rates among males (r=0.61, p=0.060) was not statistically significant. However, the increase in male to female rate ratio (r=0.87, p=0.001) and the decrease in suicide rates among females (r=-0.77, p=0.009) were statistically significant. The suicide rates among males were always higher than the suicide rates among females over time.

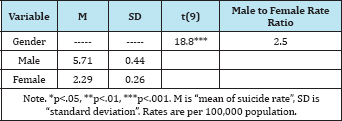

Table 4: Results of paired sample t-test.

Table 4 shows the results of the paired sample t-test and the ratio of male to female rate. The results indicated that there was statistically significant difference in suicide rates between males and females (t(8)=18.8, p<.001). More specifically, the suicide rate for males (M=5.71, SD=0.44) was higher than the suicide rate for females (M=2.29, SD=0.26). The ratio of male to female suicide rate showed that male suicide rates was 2.5 times as high as female suicide rates.

Discussion

The current study examined suicide rates by gender between 2007 and 2016 by using various statistical analyses. More specifically, the study focused on two points: First, the trends in suicide rates by gender. Second, whether there was statistically significant difference in suicide rates between females and males.

The results showed that, with respect to the trends in suicide rates by gender, there was an increase in suicide rates among males (Figure 1). However, the increase was not statistically significant (Table 3). In contrast to males, there was decline in suicide rates among females over time, and the decrease was statistically significant (Table 3). The results confirmed the first hypothesis that suicide rates increase in males while female suicide rates decrease. These findings are consistent with the previous research, which found that male suicide rates increased in Northern Ireland, Wales [21], in the US [10], and female suicide rates decreased and male suicide rates increased in Turkey [4].

However, the findings are inconsistent with the previous research, which found that in England, female suicide rates increased while male suicide rates decreased, and male suicide rates decreased in Scotland, and in the Republic of Ireland [21]. The results also indicated that there was a statistically significant increase in male to female suicide rate ratio (Figure 2 and Table 3). The findings confirmed the second hypothesis that the ratio of male to female suicide rate increases significantly over time. The findings are similar to the findings of the past research, which found that the difference in suicide rates between males and females increased [4]. In addition, the results indicated that there was a statistically significant difference in suicide rates between males and females (Table 3). Specifically, the ratio of male to female suicide rate showed that males committed suicide 2.5 times as high as females. These findings confirmed the third hypothesis that male suicide rates are significantly higher than that of females. The findings are similar to the male to female suicide ratio in the Republic of Korea [20] . However, the male to female ratio in Turkey was lower than the male to female ratio in Europe [20], in the US [10], and in the UK [21] . The result also showed that the male to female ratio increased from 1.79 between 1987 and 2011 [22] to 2.5 between 2007 and 2016 in Turkey.

Suicide rate being higher in males than in females may be attributed to the intent on dying or the lethality of suicide method used [29]. However, the past research has shown that males and females have equal intent to die [29-31]. This suggests that the difference in suicide rates between males and females is a result of method choice, rather than intent. The previous research have shown that females use less lethal suicide methods such as drug overdose and poisoning, while males use more lethal suicide methods such as firearms and hanging [31-38]. This could explain the differences in suicide rates between males and females.

The present findings have a number of practical policy implications. For males in particular, different programs should be implemented to increase their coping skills with stressful life events. Parents should be trained about how they can help their children to overcome difficulties. In schools, educational programs should be organized to increase the coping skills of students. Social services may also be beneficial to support those who are at risk of committing suicide.

The study has some limitations. First, the data was based on the agency data, which may contain some errors. Finally, the data just include the reported suicide cases, and thus, may be underestimated. It is important to note that reliable and accurate data about suicide is essential for identifying those most at risk, developing, and evaluating the effectiveness of suicide prevention programs.

Conclusion

The future studies should focus on investigating the causes of suicide by gender, and examining suicide rates by gender and age to develop more specific intervention plan. In addition, an international comparative study on suicide rates by gender should be conducted to understand better the differences across countries.

To conclude, there is an increasing trend in the ratio of male to female suicide rate, and there is a decreasing trend in female suicide rates.

References

- Crosby AE, Ortega L, Melanson C (2011) Self-directed violence surveillance: uniform definitions and recommended data elements, Version 1.0. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Atlanta, Georgia.

- Shneidman E (1977) Definition of suicide. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, USA.

- Hill D (2011) What is It to commit suicide? ratio: An International Journal of Analytic Philosophy 24: 192-205.

- Aktajand SG, Kantar YM (2016) A study of suicide mortality in turkey (2002-2011). Journal of EU Research in Business, 2016 (2016): 1-16.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2016) Global health estimates 2015: Deaths by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, Geneva, Switzerland.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2017) World health statistics 2017: monitoring health for the SDGs, Sustainable development goals. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Bilginer C, Cop E, Goker Z, Hekim O, Sekmen E, et al. (2017) Overview of young people attempting suicide by drug overdose and prevention and protection services . Suicide statistics 30: 243-250.

- Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A (2002) A global perspective in the epidemiology of suicide. Suicidology 7: 6-8.

- Cibis A, Mergl R, Bramesfeld A, Althaus D, Niklewski G, et al. (2012) Preference of lethal methods is not the only cause for higher suicide rates in males. Journal of Affective Disorders 136(1-2): 9-16.

- Curtin SC, Warner M, Hedegaard H (2016) Suicide rates for females and males by race and ethnicity: United States, 1999 and 2014. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

- DeJong TM, Overholser JC, Stockmeier CA (2010) Apples to oranges? A direct comparison between suicide attempters and suicide completers. Journal Affective Disorders 124(1-2): 90-97.

- Durkheim E (1897) Suicide. J A Spaulding & G Simpson, Free Press, New York, USA.

- Fushimi M, Sugawara J, Saito S (2006) Comparison of completed and attempted suicide in Akita, Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 60(3): 289295.

- Giner L, Fontecilla BH, Rodriguez M, Nieto GR, Giner J, et al. (2013) Personality disorders and health problems distinguish suicide attempters from completers in a direct comparison. Journal Affective Disorders 151(2): 474-483.

- Wang S, Kim T, Seo H, Jeong J, et al. (2016) Factors associated with suicide completion: A comparison between suicide attempters and completers. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry 8(1): 80-86.

- Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R (2002) World report on violence and health. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Oner S, Yenilmez C, Ayranci U, Gunay Y, Ozdamar K (2007) Sexual differences in the completed suicides in Turkey. European Psychiatry 22(4): 223-228.

- Uribe PI, Fontecilla BH, Pares GG, Batalla MG, Capdevila ML, et al. (2013) Attempted and completed suicide: not what we expected? Journal of Affective Disorders 150(3): 840-846.

- Suicide Awareness Voices of Education (2013) Suicide facts, USA.

- World Health Organization (2015) Global health observatory (GHO) data. Suicide Rates, USA.

- Scowcroft E (2017) Samaritans. Suicide statistics report 2017.

- Doğan N, Toprak D (2015) Trends in suicide mortality rates for Turkey from 1987 to 2011: A join point regression analysis. Arch Iran Med 18(6): 355-361.

- Kreitman N (1976) The coal gas story: United Kingdom suicide rates, 1960-71. Br J Prev Soc Med 30(2): 86-93.

- TUIK (n.d.b) Duties and authorities, Turkey

- TUIK (n.d.c.) Vital statistics, Turkey

- TUIK (n.d.c) Address based population registration system, Turkey

- Anderson RN, Rosenberg HM (1998) Age standardization of death rates: Implementation of the year 2000 standard. National Vital Statistics Reports 47(3): 1-17.

- De Winter JC (2013) Using the student's t-test with extremely small sample sizes. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation 18(10): 1-12.

- Canetto SS, Sakinofsky I (1998) The gender paradox in suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav 28(1): 1-23.

- Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, Mulder RT, Fergusson DM, Nightingale SK (1996) Prevalence and comorbidity of mental disorders in persons making serious suicide attempts: A case-control study. American Journal of Psychiatry 153(8): 1009-1014.

- Denning DG, Conwell Y, King D, Cox C (2000) Method choice, intent, and gender in completed suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav 30(3): 282-288.

- Baker SP, Hu, G, Wilcox HC, Baker TD (2013) Increase in suicide by hanging/suffocation in the US, 2000-2010. Am J Prev Med 44(2):146- 149.

- Cantor CH (2000) Suicide in the western world. In: Hawton K, van Heeringen K (Eds.), The international handbook of suicide and attempted suicide, John Wiley & Sons, Sussex, UK, pp. 9-28.

- Chehil S, Kutcher S (2012) Suicide risk management: A manual for health professionals (2nd edn), John Wiley & Sons, Sussex, UK.

- Demir M (2017) Gender differences in suicide methods in Turkey Forensic Res Criminol Int J 4(6): 00133.

- Demir M (2018) Suicide methods by gender and age in Turkey. J Forensic Res Anal 2(1).

- Shenassa ED, Catlin SN, Buka SL (2003) Lethality of firearms relative to other suicide methods: a population based study. Journal of epidemiology and community health 57(2): 120-124.

- Varnik A, Kolves K, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Marusic A, Oskarsson H, et al. (2008) Suicide methods in Europe: a gender-specific analysis of countries participating in the European alliance against depression. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 62(6): 545-551.

___________________________

1Crude or unadjusted suicide rate is simply the number of suicides divided by the population at risk, and multiplied by generally 100,000. Gender specific suicide rate is simply a crude suicide rate for a specific gender group.

2 Pearson's correlation assesses linear relationships between continuous variables.

3 The paired sample t-test can be used to test either a "change" or a "difference" in means between two sets of observations.

4This study shows that a t-test is feasible with extremely small sample sizes.

© 2018 Mustafa Demir. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)