- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Reviews & Research

Effects of School Menstrual Hygiene Management, Water and Sanitation Interventions on Girls’ Hygiene Knowledge, Services and Hygiene Practices: Lasta District, Amhara Region, Ethiopias

Fisseha Atale Andargie1* and Tinuola Femi Rufus2

1School of Public Health, University of Central Nicaragua, Nicaragua

22Department of Sociology, Federal University, Gusau. Zamfara State, Nigeria

*Corresponding author:Fisseha Atale, University of Central Nicaragua, Managua, Nicaragua

Submission: May 24, 2025; Published: June 10, 2025

ISSN 2639-0590Volum4 Issue5

Abstract

This study evaluated the effects of school-based Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM), water and sanitation (WASH) interventions on hygiene knowledge, access to services and hygiene practices among menstruating girls. Using a combination of cross-sectional and experimental designs, along with mixed methods, quantitative and qualitative, the research identified significant improvements across multiple domains. Key findings revealed that peer-to-peer education and teacher involvement played a critical role in enhancing girls’ hygiene knowledge, which had previously been predominantly shaped by family members, particularly mothers and sisters. Girls from intervention schools exhibited significantly higher levels of MHM knowledge compared to their peers in non-intervention schools. The intervention also led to notable improvements in access to essential hygiene facilities and services within schools, including the availability of sanitary products, gender-segregated latrines, menstrual hygiene management rooms and safe drinking water. Consequently, a higher proportion of girls in the intervention schools reported using disposable sanitary pads and practicing genital hygiene during school hours compared to those in nonintervention schools. In conclusion, school-based MHM education and WASH interventions significantly improve girls’ menstrual hygiene knowledge and knowledge sources, access to hygiene facilities and services and overall hygiene practices.

Keywords:Menstrual hygiene management education; Hygiene knowledge; Access to hygiene services; Hygiene practices/behaviour; Menstruation; Water; Sanitation and hygiene (Wash) services

Introduction

Menstruation is a physiological process involving the monthly shedding of the uterine lining, occurring among pubertal girls and pre-menopausal women who are not pregnant [1,2]. Menstrual hygiene management, by contrast, entails the hygienic handling of menstrual blood flow through appropriate sanitary products and practices, including the use of absorbent materials, soap, water and safe disposal of used products [1-3]. Improving hygiene knowledge and practices among menstruating girls has posed a longstanding challenge in developing countries, largely due to the stigmatization of menstruation, which has kept it off the public agenda [4]. However, since the early 21st century, this issue has gained attention in school settings, thanks in part to the involvement of private and non-governmental organizations [5]. Despite these efforts, the impact of school-based menstrual hygiene and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) interventions on female students remains under-researched.

Over the past two decades, research has underscored the significant challenges of menstrual hygiene management as a public health issue, revealing that inadequate hygiene education has led to unsafe practices among girls. For instance, a systematic review on menstruation and Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) in Ethiopia found that approximately 50% of girls did not practice safe hygiene management [6]. Similarly, studies conducted in Ambo Town in Western Ethiopia and the Gedeo Zone in Southern Ethiopia indicated that 53% and 60.3% of girls, respectively, engaged in unsafe hygiene practices [7,8]. In Bangladesh and India, the situation was equally concerning, with 69% of girls relying on old or unsafe clothing and many using no absorbent materials at all [9]. Significant disparities exist in hygiene knowledge and practices between urban and rural female students, largely due to differences in resource access and information. For example, a study on urban girls in Ethiopia found that hygiene knowledge ranged from 50% to 75% [10,11]. Similarly, research in urban Nigeria indicated that hygiene knowledge and practice rates among girls were 76% and 70%, respectively [12]. These disparities not only impact hygiene practices but also increase girls’ vulnerability to issues like unwanted pregnancies [13].

To improve hygiene practices among female students, studies recommend that schools provide comprehensive hygiene education and access to adequate water, sanitation and hygiene services. Such measures are essential for fostering a supportive environment that promotes girls’ health and well-being during menstruation [7,8,10]. For instance, studies in Kenya and Ethiopia on school-based WASH interventions show that access to these services not only improves hygiene practices but also positively influences girls’ class attendance [14-16]. Most studies on girls’ hygiene knowledge and practices have primarily been non-pilot studies, focusing on female students’ knowledge, attitudes and hygiene behaviours, mainly in urban settings [10-12,15]. Although these studies highlight the importance of school-based WASH interventions, they have not assessed their impact on girls’ hygiene knowledge, service access, or hygiene practices.

Evaluations by UNICEF and Emory University in the Philippines found that school WASH interventions empower girls by enhancing their hygiene knowledge and self-confidence [17]. Similarly, UNICEF and Columbia University highlight WASH interventions as empowering tools for female students in their annual reports [18]. However, these evaluations primarily focus on qualitative findings without quantifying the impact of WASH interventions on girls’ hygiene knowledge and practices. Pilot studies conducted in Kenya, Ethiopia and Nepal have examined the impacts of school WASH interventions on female students. The Ethiopian and Kenyan studies reported that WASH interventions not only improve hygiene practices but also class attendance among girls [14,16]. Conversely, the Nepal study found that while WASH interventions were positively associated with improved hygiene practices, they did not significantly affect class attendance [19].

However, none of these pilot studies fully considered comprehensive school WASH service provision to assess their effect on menstruating female students. For example, the Ethiopian study included MHM education, sanitary products and underwear supply but lacked access to water and latrines [16], The Nepal study provided only sanitary products and instructions for use, without access to water, gender-segregated latrines, or hygiene education [19]. In Kenya, the intervention lacked access to sanitary product, hygiene education and direct access to potable water, offering disinfectants only [14]. These limitations suggest that existing pilot studies do not sufficiently evaluate the influence of comprehensive school WASH interventions on menstruating girls. Moreover, neither pilot nor non-pilot studies have adequately considered external factors, such as policy influence, community dynamics and peer influences, which affect girls’ hygiene knowledge and practices [10-12,14-16,19]. Both school and external environments are key to influence girls’ hygiene behaviours [20].

As a result, currently there is a lack of strong evidence on the effects of school MHM education and WASH interventions on girls’ hygiene knowledge, access to services and hygiene behaviour [21]. However, previous findings have laid the groundwork for further studies. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of both external factors (policy and social relationships) and internal factors (school menstrual hygiene management education and access to WASH services, including school social dynamics) on girls’ menstrual hygiene knowledge, access to services and hygiene practices. The study was based on a six-year school menstrual hygiene management education that integrated comprehensive WASH services and actively involving both girls and boys, as well as teachers. This full package school-based interventions would help close knowledge gaps noted in previous studies, improve the design of school WASH intervention and initiate further studies on school programs.

Methods

Study setting

The researcher conducted the study in Lasta District, situated in North Wollo Zone of Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. Plan International Ethiopia, a nongovernmental organization, implemented the school-based MHM education and WASH interventions in 10 primary second-cycle schools in the district from July 2018 to March 2024. While Plan International Ethiopia implemented the school interventions, the Government of Netherlands, through its Foreign Affairs Office, based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, funded the school WASH interventions. For the study, six primary second-cycle schools were sampled: -three from the intervention schools and another three from control/nonintervention schools.

Components of school MHM and WASH interventions

The intervention comprised MHM education, distribution of sanitary pads and soap and access to water and gender-segregated toilets. It also constructed MHM rooms where girls could rest, change pads, prepare sanitary products and engage in peer-led education. In contrast, control schools lacked these facilities and received only basic MHM awareness from the District Women and Children Affairs Office. Due to the local government budget limitation and the absence of external WASH service provision support, most schools in the district, including control schools, did not receive MHM and WASH services. Regarding frequency of support by the program, long-term infrastructures, such as latrines and MHM rooms, have been built for sustained use, while consumables like pads and soap required ongoing replenishment.

Girls received sanitary materials twice, including fabric for making reusable pads and soap on two occasions. To cope with shortages, they contributed small monthly amounts to buy additional soap. Girls received MHM education until all students, including boys, were trained. The school MHM clubs continued monthly monitoring, supported new female students and organized yearly trainings. The program aimed to build local capacity among girls, teachers and education officials to sustain MHM practices independently and reduce reliance on external support. Spanning from July 2018 to March 2024, Plan International was implementing the school program primarily during school terms, with some interruptions during breaks, the COVID-19 pandemic and local conflicts. Plan International Ethiopia, together with district officials and teachers, conducted regular follow-ups to strengthen girls’ MHM skills and address service gaps.

Study design

The study employed a cross-sectional design because the school interventions began in July 2018, while the study began in April 2023. This timing made a longitudinal design impractical, as it prevented baseline data from being compared with intervention outcomes. Instead, the study compared intervention schools with control schools that had not received similar interventions. Although random sampling was used to select both schools and participants, neither schools nor girls could switch groups. Girls in intervention schools had no opportunity to be included in the control group and the same applied to girls in control schools. As a result, the study followed a quasi-experimental design.

Methods and data collection instruments

The study triangulated qualitative and quantitative methods to address limitations of a single approach. Qualitative data collection instruments, including focus group discussions, key informant interviews and observations, were conducted first and informed the quantitative phase while the quantitative data were collected through questionnaires.

Study population

The study aimed to assess the effects of school interventions on menstruating girls, who formed the main study population. To explore the influence of communities, peers and policies on girls’ MHM practices, male students, mothers and district office heads were included in the qualitative data collection.

Ethical issues

Participant Assent: Girls were briefed on the study a day before participation and gave written assent the next day after discussing with parents and peers.

Guardian Consent: Two days prior, schools and the Parent and Teachers Association (PTA) held a meeting with parents, who gave verbal consent. Parents in focus group discussions provided written consent.

Institutional Consent: Written approval was also obtained from the study district: -Lasta District Education Office.

Sampling method and sample size

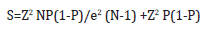

The study used stratified sampling to group schools based on access to MHM education and WASH services. From 10 intervention and 25 control schools, three schools were randomly selected from each group. A multi-stage sampling approach was used to select participants. Of the 1,214 total students across six schools, 626 were menstruating girls, 333 from intervention and 293 from control schools. Using a sample size formula, an initial sample of 240 was determined. To account for potential nonattendance due to the wedding season and local security concerns, the sample was increased by 19% (120 girls), resulting in a final sample of 360: 192 from intervention and 168 from control schools. All selected participants were present, yielding a 100% response rate. Within schools, a proportional sample was allocated and participants were randomly selected using a lottery method from lists of menstruating girls. The study used 95% confidence level, 5% margin of error, 0.5 variance and finite population formula, detailed as follows [22]: -

Where;

S: Stands for sample size

N: Population size of students

P: Population proportion, with an expected variance of 0.5

Z: Z score, which is 1.96 in this case;

e- Margin of error/degree of accuracy, which is 0.05 (5%);

Data quality control

To minimize contamination risk in control schools, the study used geographical isolation as its primary strategy. Both intervention and control schools were located in rural areas with sparse populations and substantial distances between them. Due to concerns about gender-based violence and safety, girls in these regions rarely travelled far for school; so only, those living nearby could continue their education. This isolation effectively limited the spread of MHM knowledge from intervention to control schools.

Additionally, before selecting control schools, the research team confirmed that no MHM knowledge was transferred and that no other WASH interventions were present in or near them. Contamination was therefore mitigated by choosing rural schools with similar characteristics, verifying the absence of related programs and ensuring no intentional knowledge exchange occurred. To limit potential data collector bias, the research team provided training with a strong focus on maintaining neutrality. To control the researcher’s bias, the study employed a mixed-methods approach; analysed the data using the independent samples t-test and employed socio-ecological perspective that helped avoid confirmation bias.

Moreover, the following strategies were set to mitigate the

effects of extraneous variables:

A. Restriction: The sample was limited to the girls, aged 13-15

in Grades 7 and 8, ensuring similar age and educational levels.

B. Matching: Intervention and control groups were matched

based on family background, income, technology exposure

and school setting. All schools were in remote rural areas with

similar socioeconomic conditions.

C. Transportation & Academic Performance: Nearly all

students walked to school on foot and mid-year 2024 academic

data was used to control for prior performance.

D. Teaching Quality: All schools had limited resources and no

advanced training, minimizing differences in teaching quality.

E. Cultural & Religious Similarity: Most participants were

Amhara (98%) and Orthodox (84%), reducing cultural and

religious variability.

Data collection

After data collectors’ training and pilot testing on March 7 and 8, 2024, respectively, the data collector team conducted data collection from March 11 to 15, 2024.

Statistical methods used

After organizing the data, the researchers performed cleaning, coding and entry into spreadsheets. Qualitative data were analysed thematically, while quantitative data were processed using SPSS. Descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) summarized the responses and independent samples t-tests were used to assess statistical significance. Finally, qualitative and quantitative findings were integrated to evaluate the research hypotheses.

Results and Discussion

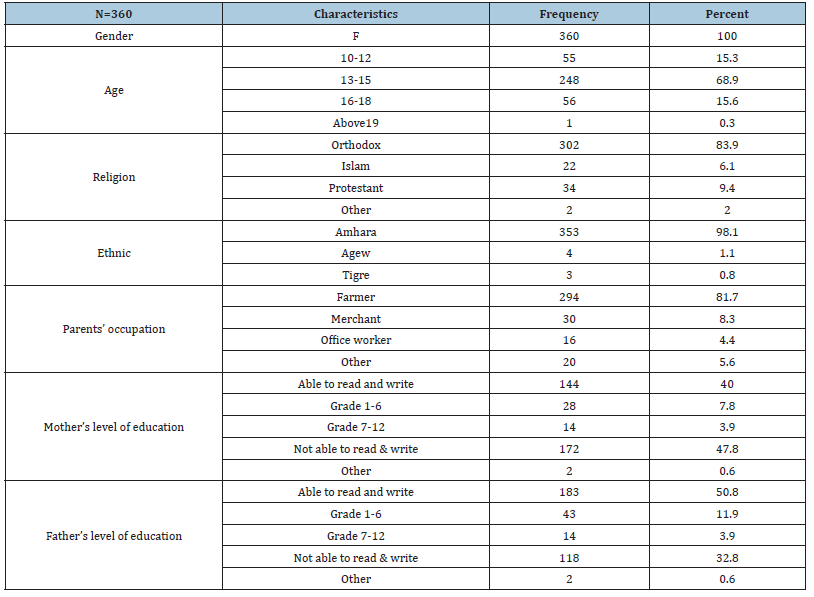

Result Demographic characteristics

The majority of menstruating students were aged 13 to 15 years (68.9%), followed by those aged 16 to 18 years (15.6%) and 10 to 12 years (15.3%). Among the surveyed girls, 97.8% identified as Amhara, while 1.1% identified as Agew and 0.8% as Tigre. In terms of religious affiliation, 83.9% identified as Orthodox, 9.4% as Protestant and 6.1% as Muslim (Table 1).

Regarding parental education, 66.2% fathers were able to read and write versus 51.7% of mothers; while the illiteracy rate among mothers was 47.8% compared to 32.8% of fathers. Economically, agriculture contributed 81.7% of parents’ income and only 8.3% of the family income came from business (Table 1).

Table 1:Demographic characteristics of the sample.

Sources of girls’ menstrual hygiene knowledge Qualitative findings

A. School clubs and government support: In accordance with national policy, government schools operate various student clubs, including girls’ clubs. These clubs aim to raise awareness on key topics such as Menstrual Health Management (MHM). To support these efforts, the district-level Women and Children Affairs Office provides training for selected teachers, equipping them to lead and facilitate MHM-related activities within these clubs.

B. Sources of MHM knowledge: Girls reported receiving MHM information from a range of sources, including mothers, sisters, peers and teachers. Mothers in both treatment and control schools commonly stated: “We discuss menstruation and menstrual hygiene management with our daughters openly.” Girls acknowledged the important role of mothers, sisters and teachers. However, those in treatment schools highlighted school-based promotion and peer-to-peer education as their primary sources of knowledge.

C. Differences in Teacher Observations: Teachers in treatment schools believed that girls were well informed about MHM and felt comfortable discussing menstruation with both teachers and peers. In contrast, teachers in control schools noted that girls lacked adequate knowledge and were reluctant to discuss the topic, with one remarking: “Girls do not have adequate knowledge of MHM and are afraid to discuss it with others.”

Quantitative findings

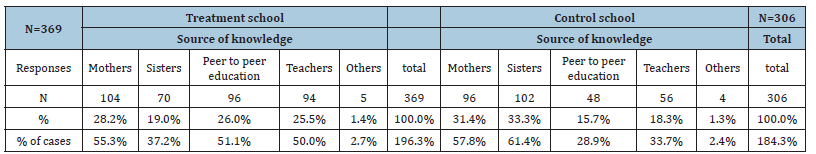

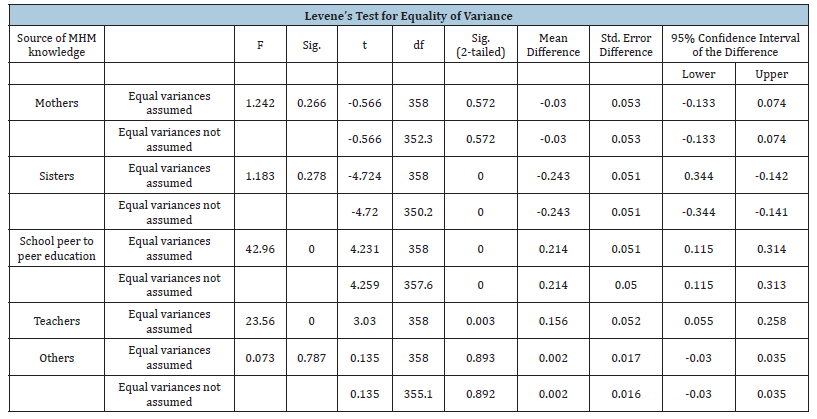

In treatment schools, 55.3% of girls reported their mothers as a primary source of MHM knowledge, followed by 51.1% who cited peer-to-peer education and 50.0% who mentioned teachers. By contrast, 61.4% of the girls in the control schools cited their sisters, 57.8% their mothers and 33.7% mentioned teachers (Table 2). To assess the significance of differences in sources of MHM knowledge between treatment and control schools, a t-test was conducted. The results (Table 3) showed statistically significant differences, with p-values of 0.001 for peer-to-peer education, 0.001 for sisters and 0.003 for teachers. All p-values were below the alpha level of 0.05 (0.001 < 0.05 and 0.003 < 0.05).

Table 2:Girls’ source of menstrual hygiene knowledge.

Table 3:T test results on girls’ source of menstrual hygiene knowledge.

Girls’ menstrual hygiene knowledge

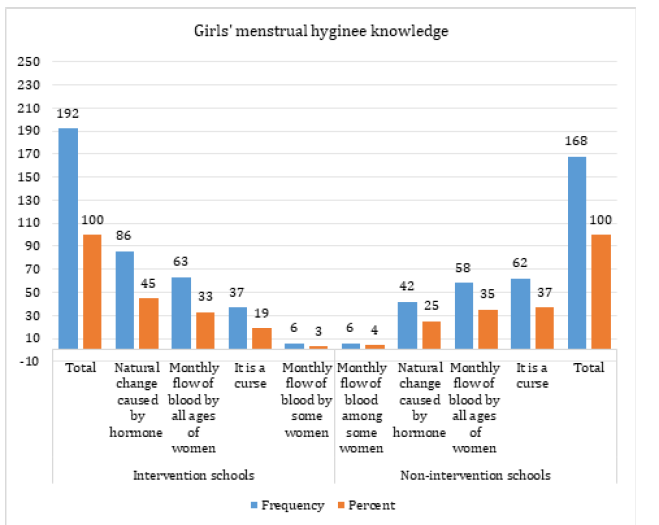

While all girls reported general awareness about menstruation, primarily through government initiatives and school clubs, differences in understanding were observed between girls from intervention and non-intervention schools. As shown below (Figure1), 44.8% of girls in treatment schools perceived menstruation as a natural biological process caused by hormones, compared to 25.0% in control schools. In contrast, 36.9% of girls in control schools viewed menstruation as a curse, whereas only 19.3% of girls in treatment schools held this belief.

Figure 1:Disparities in perceptions of menstruation among schoolgirls.

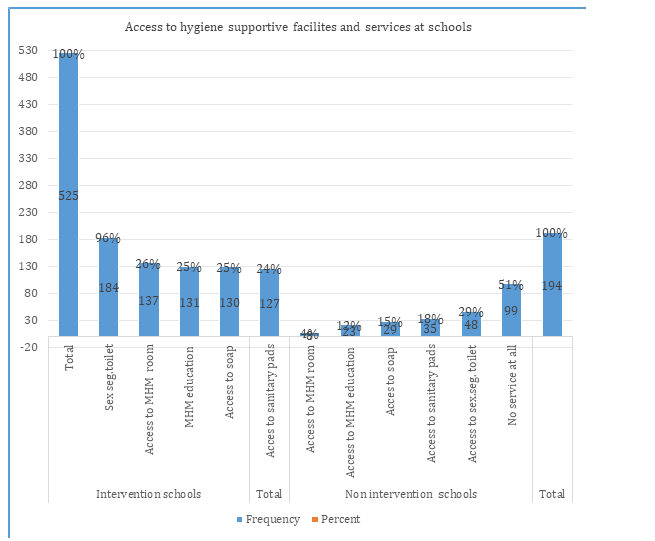

School facility and resource availability

Qualitative observations of school facilities indicated that while

all treatment and control schools had washable toilets, only the

treatment schools had sex-segregated toilets with internal locks and

handwashing facilities. Furthermore, girls’ clubrooms were present

in all treatment schools, but none were found in control schools.

Mothers and girls from treatment schools reported the availability

of sanitary products, water and soap within the school environment.

In contrast, participants from control schools-both girls and their

mothers-expressed concerns about the lack of sanitary pads, soap

and access to water. Quantitative data supported these findings.

Among girls surveyed, 26.1% in treatment schools recognized the

availability of girls’ clubrooms, compared to only 4.1% in control

schools. Reports of access to key menstrual hygiene resources were

consistently higher in treatment schools:

a) Access to soap: 25% (treatment) vs. 15% (control)

b) Availability of sanitary pads: 24% (treatment) vs. 18%

(control)

c) Access to MHM education: 25% (treatment) vs. 12% (control)

(Figure 2)

Figure 2:Comparison of hygiene management facilities and resource availability between intervention and nonintervention schools.

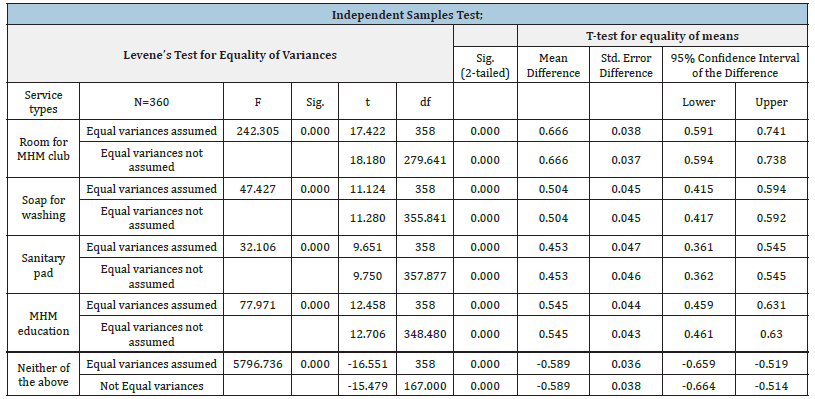

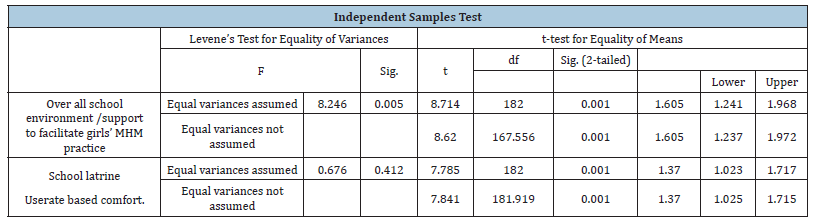

A significant difference in access to hygiene management facilities and service availability was observed based on an independent samples test, with all services yielding p-values of 0.001. This is well below the 0.05 significance threshold (p < α; 0.001 < 0.05), as shown in Table 4.

Table 4:T-test results on hygiene supportive school facilities and services.

Menstrual hygiene management practices among schoolgirls Sanitary products in use

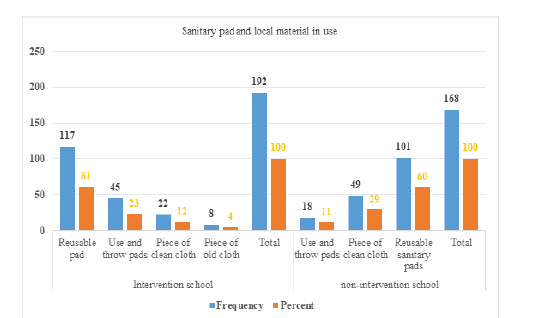

In terms of menstrual hygiene product utilization, girls in treatment schools, 23.4%, reported using disposable sanitary pads compared to 10.7% of the girls in control schools. In contrast, 29.2% of the girls in control schools used non-fabric cloths against 11.5% of the girls in treatment schools (Figure 3). However, the use of reusable sanitary pads was nearly the same rate in both groups, 60.9% in treatment schools and 60.1% in control schools. This quantitative finding, however, stands in contrast to qualitative data from interviews, where both mothers and girls denied using reusable sanitary products.

Figure 3:Comparison of sanitary product and local material use among girls in intervention and non-intervention groups.

Genital hygiene management practices among girls

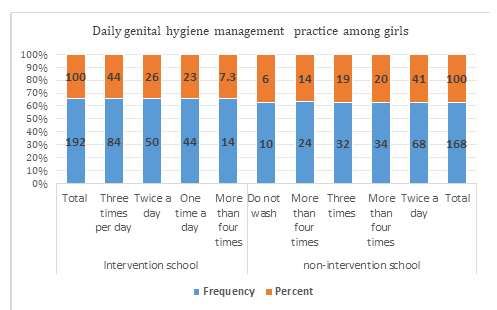

The study found that 43.8% of girls in treatment schools practiced genital hygiene three times per day during menstruation, compared to 19% in control schools. In contrast, 40.5% of girls in control schools practiced genital hygiene twice per day, while 26% of girls in treatment schools did the same. Overall, 51.1% of girls in treatment schools reported practicing genital cleaning three to four times per day, compared to 33.3% in control schools (Figure 4).

Figure 4:Comparison of daily genital hygiene practices among menstruating girls in intervention and nonintervention schools.

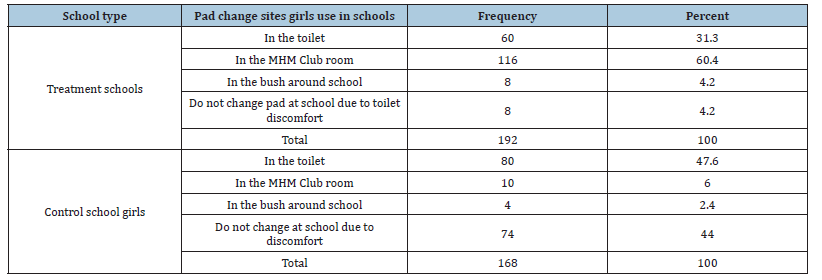

Menstrual hygiene management facilities used by girls for changing sanitary pads in schools

One of the key objectives of the school MHM and WASH interventions was to empower girls to manage their menstrual hygiene at school, thereby reducing absenteeism. The findings show that 91.7% of girls in treatment schools changed their sanitary pads using MHM clubrooms and toilets, compared to 53.6% of girls in control schools. In contrast, 44% of girls in control schools did not change their sanitary pads at school, whereas only 4.2% of girls in treatment schools skipped this practice (Table 5). The difference in menstrual hygiene management practices between girls in intervention and non-intervention schools was statistically significant, as shown by an independent samples t-test (p=0.001), which is below the 0.05 significance threshold (p < α; 0.001 < 0.05) (Table 6).

Table 5:Significance of school MHM clubrooms and sex segregated latrines to facilitate girls’ sanitary pad change in schools.

Table 6:T- test results on school facility comfort for MHM.

Discussion

The demographic analysis indicated that the majority of participants were girls aged 13-15 years, comprising 69% of the sample. This was followed by girls aged 16-18, who made up 16% and those, aged 10-12, accounting for 15%. Ethnically, 98% of the participants identified as Amhara, with smaller percentages identifying as Agew (1%) and Tigre (0.8%). Regarding religion, 84% of the girls identified as Orthodox, 9% as Protestant and 6% as Muslim. The analysis of parental education levels revealed low literacy rates, with 66% of fathers able to read and write, compared to 52% of mothers. Household income was predominantly derived from agriculture (82%), while a smaller portion (8.3%) relied on business ventures (Table 1). Therefore, the study population is highly homogeneous, particularly in terms of ethnicity, religion and economic activity, highlighting the importance of controlling for variables that could influence research outcomes beyond the intervention.

Menstrual hygiene knowledge among menstruating girls

The study revealed that girls obtained menstrual hygiene knowledge from both home-based and external sources. At home, primary sources included sisters and mothers and other female relatives. Externally, knowledge was acquired through local government initiatives driven by policy, peer-to-peer education in schools and instruction from teachers. However, the degree of reliance on these sources differed between girls attending intervention schools and those in control schools. Girls from intervention schools primarily relied on mothers (55.3%), peerto- peer education (51.1%) and teachers (50.0%). Conversely, girls from non-intervention/control schools turned to their sisters (61.4%), mothers (57.8%) and least to teachers (33.7%) (Table 2).

Thus, girls from non-intervention schools relied more heavily on home-based sources, such as their sisters, followed closely by their mothers and were less likely to consult teachers than girls from intervention schools. Reliance on sisters and mothers differed significantly (61.4% vs. 57.8%). In contrast, girls in intervention schools drew on a broader range of menstrual hygiene sources both at home and outside the home, including mothers, peer-topeer education and teachers, with more balanced use across these sources. This variation may be attributed to access to Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) education in schools. Girls in the control schools, who did not receive MHM education, relied more on their sisters and mothers, with a stronger dependence on sisters, suggesting a lack of confidence in discussing such topics with their mothers. In contrast, girls in the treatment schools drew proportionally on peer-to-peer education, teachers and their mothers as sources of menstrual hygiene knowledge. This more balanced reliance likely resulted from the MHM education provided at school, which facilitated open discussions with peers and teachers in addition to mothers.

The variation in the sources of MHM knowledge significantly influences girls’ understanding of menstruation. For example, 44.8% of girls in intervention schools identified menstruation as a natural process caused by hormonal changes, compared to only 25% in control schools. Conversely, 36.9% of girls in nonintervention schools perceived menstruation as a curse, whereas this belief was held by just 19.3% of girls in intervention schools (Figure 1). This disparity may stem from the broader range of MHM information available in intervention schools, where peerto- peer education and teachers who support school MHM clubs help fill the knowledge gaps often left when girls rely solely on their mothers and sisters. The difference in sources of menstrual hygiene knowledge between the two groups of female students was further supported by t-test results, with p-values of 0.001 and 0.03-both below the significance level of 0.05. Thus, the results are statistically significant (p < α), confirming a meaningful difference between the groups (Table 3). Moreover, the findings align with studies from Nigeria and Ethiopia, which highlighted that girls with diverse sources of MHM information and from educated families have a better understanding of menstruation and menstrual hygiene management [10,12,15].

Availability of menstrual hygiene management facilities and services in schools

To enable menstruating girls to practice safe Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) in schools, it is crucial to provide appropriate hygiene facilities, foster a supportive social environment and implement targeted educational initiatives. Both qualitative and quantitative findings indicated that girls in intervention schools had significantly better access to MHM resources. Quantitative data revealed that 26.1% of girls in intervention schools had access to designated MHM clubrooms, compared to only 4.1% in control schools. Similarly, 24.8% had access to soap versus 14.9% and 24.2% had access to sanitary pads compared to 18%. Notably, 51% of girls in control schools reported a complete lack of essential MHM services, including access to soap, sanitary products, dedicated girls’ spaces and hygiene education (Figure 2).

T-test results on access to hygiene-supportive school facilities and services yielded p-values below 0.05, indicating that schoolbased MHM and WASH interventions significantly improved girls’ access to essential menstrual hygiene management facilities and services and contributed to a supportive social environment in schools (Table 4). Access to essential MHM facilities and services had a direct impact on girls’ menstrual hygiene practices at school, which in turn positively influenced their class attendance (Figure 4). While previous studies did not directly quantify the impacts of school interventions on girls’ access to hygiene facilities and services, they consistently suggested that such hygiene services at schools enhance girls’ hygiene behaviour. For example, a study in the Philippines identified WASH facilities as key determinants in empowering menstruating girls [17]. Similarly, research in Niger emphasized the role of school infrastructure and access to WASH services in promoting positive hygiene behaviours among girls [23].

Menstrual hygiene management practice among girls at school: The earlier discussions on Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) facilities and services, along with knowledge levels, revealed a significant disparity between girls in intervention and non-intervention schools. Girls in intervention schools had notably better access to MHM services and demonstrated greater menstrual hygiene knowledge, which contributed to a marked difference in hygiene practices between the two groups. Qualitative insights from mothers and girls indicated a strong preference for disposable sanitary pads, largely due to maternal concerns about potential health risks associated with reusable options. Teachers in intervention schools observed that girls actively used sex-segregated toilets and dedicated MHM clubrooms to manage their hygiene during menstruation. In contrast, teachers in control schools reported that girls were reluctant to change sanitary products at school due to the absence of clean water, sanitary supplies and fears of ridicule or negative comments from male peers.

Quantitative data further underscored these disparities. In intervention schools, 23.4% of girls used disposable sanitary products, compared to only 10.7% in control schools. Conversely, reliance on cloth as a menstrual absorbent was significantly higher in control schools (29.2%) than in intervention schools (4.2%) (Figure 3). The higher use of disposable sanitary products among girls in treatment schools may be attributed to their increased empowerment through MHM education, which enabled them to influence and negotiate with their parents regarding the purchase of non-reusable sanitary pads (Table 2). This suggests that MHM interventions not only improved access to sanitary products but also increased agency among girls in making decisions related to menstrual hygiene. The notable discrepancy between qualitative and quantitative findings on the use of reusable sanitary products, 0% reported in interviews versus 60% in surveys, may reflect the influence of social stigma. During face-to-face discussions, girls and their mothers may have been reluctant to admit to using reusable products, possibly due to concerns about social perceptions or fears of being judged for economic limitations. In contrast, the anonymity of the questionnaires likely provided a safer space for honest disclosure, revealing a significant underreporting in qualitative responses.

Genital hygiene practices during menstruation were notably better among girls in treatment schools compared to those in control schools. Specifically, 43.8% of girls in treatment schools reported washing their genitals three times per day, whereas only 19% of girls in control schools did the same. Conversely, 40.5% of girls in control schools reported washing twice daily, compared to just 26% in treatment schools. Overall, 51.1% of girls in intervention schools practiced genital washing three to four times per day, in contrast to 33.3% of girls in control schools (Figure 4). Moreover, a significantly higher proportion of girls from intervention schools (91.7%) reported practicing menstrual hygiene management at school, compared to 53.6% in control schools. This improvement is largely attributed to the availability of supportive physical infrastructure, such as access to water, private toilets and sanitary supplies, as well as a more enabling and stigma-free social environment in intervention schools (Figure 2 & Table 2).

Therefore, a higher proportion of menstrual hygiene management practices in schools is associated with a lower level of class absenteeism during menstruation and vice versa. Furthermore, an Independent Samples T-test assessing differences in hygiene behaviour between treatment and control schools yielded a p-value of 0.001, indicating a statistically significant difference in menstrual hygiene management practices among girls in the treatment and control schools (Table 6). Overall, the findings revealed clear differences in the use of sanitary products and Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) practices between girls in treatment and control schools. These differences were attributed to varying levels of access to hygiene infrastructure, services and social environments across the schools.

These results are consistent with findings from Tigray, Northern Ethiopia, which indicated that the provision of sanitary pads and MHM education was associated with improved hygiene practices [16]. Similarly, a study in Nepal and Amhara Regional State of Ethiopia reported enhanced hygiene behaviour of menstruating girls following access to menstrual hygiene management services and facilities [19,24]. In contrast to the studies from Nepal and Northern Ethiopia, the findings of this study are based on a comprehensive school-based intervention that integrated hygiene education, supportive physical infrastructure, essential services and enabling social environments both within and beyond the school setting. These combined elements contributed to shaping girls’ hygiene behaviours.

Conclusion

This study examined the effects of Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) education and WASH interventions on menstrual hygiene knowledge, access to hygiene facilities and services and hygiene behaviours among menstruating girls. The results demonstrated a strong association between improved MHM outcomes and the implementation of school-based MHM education and WASH interventions. The interventions exposed menstruating girls to diverse sources of MHM information, including peer-to-peer learning and teacher-led education, in addition to traditional sources such as mothers and sisters. This broad exposure significantly enhanced MHM knowledge among girls in the intervention schools compared to those in the control schools.

Moreover, the findings indicated that school-based interventions markedly improved access to hygiene facilities and services. These included the availability and use of Girls’ Club Rooms (MHM clubrooms), which served as spaces for changing sanitary products and sharing information on menstrual hygiene. Access to water, sanitary products and sex-segregated latrines was also considerably better in the intervention schools, in contrast to the control schools where such services were largely absent. The combined effect of improved access to information, enhanced knowledge and better hygiene infrastructure translated into more effective MHM practices among girls in the intervention schools. Specifically, a greater proportion of these girls reported using disposable sanitary products, changing pads at school-mainly in the MHM clubrooms-and practicing genital hygiene three times daily.

Adopting a socio-ecological perspective, this study considered not only school-based factors but also broader policy and social influences. The findings highlight that girls’ menstrual hygiene behaviours are shaped by both in school and out-of-school environments. While all schools in the study district demonstrated a baseline level of MHM awareness due to policy directives, the roles of mothers, sisters, peers and access to sanitary products within or near school settings were critical in supporting or constraining MHM practices. The study contributes to closing key knowledge gaps concerning menstrual hygiene practices in schools. Based on a comprehensive intervention spanning over six years-unlike many previous non-intervention studies-these findings offer a valuable foundation for future research. In addition, the results have practical implications for the design of more effective school-based WASH programs and call for the active engagement of governments and non-governmental organizations working to improve school attendance and empower menstruating girls. Future research will be essential to assess the long-term sustainability of school-based WASH interventions and to identify opportunities for programmatic refinement and contextual adaptation.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Ato Yalew Tizazu and Wondemu Sisay for their invaluable support in data collection. We also extend our appreciation to the Lasta District Education Office for granting permission to conduct the research and to the teachers who facilitated the data collection process.

References

- Ethiopian Ministry of Health (2018) National adolescent and youth health strategy.

- Crofts T, Coates S, Fisher J (2014) Menstruation hygiene management for schoolgirls.

- Bhusal CK (2020) Practice of menstrual hygiene and associated factors among adolescent school girls in dang district, Nepal. Adv Prev Med 2020: 1292070.

- Tamiru S, Mamo K, Acidria P, Mushi R, Ali CS, et al. (2015) Towards a sustainable solution for school menstrual hygiene management: cases of Ethiopia, Uganda, South-Sudan, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe. Waterlines 34(1).

- Sommer M, Hirsch JS, Nathanson C, Parker RG (2015) Comfortably, safely, and without shame: defining menstrual hygiene management as a public health issue. Am J Public Health 105(7): 1302-1311.

- Sahiledengle B, Atlaw D, Kumie A, Tekalegn Y, Woldeyohannes D, Agho KE (2022) Menstrual hygiene practice among adolescent girls in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos One 17(1): e0262295.

- Seifadin AS, Willi W, Abuzumeran A (2020) Factors affecting menstrual hygiene management practice among school adolescents in ambo, Western Ethiopia, 2018: a cross-sectional mixed-method study. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 13: 1579-1587.

- Belayneh Z, Mekuriaw B (2019) Knowledge and menstrual hygiene practice among adolescent school girls in southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 19(1).

- Haque SE, Rahman M, Itsuko K, Mutahara M, Sakisaka K (2014) The effect of a school-based educational intervention on menstrual health: An intervention study among adolescent girls in Bangladesh. BMJ Open 4(7): e004607.

- Bulto GA (2021) Knowledge on menstruation and practice of menstrual hygiene management among school adolescent girls in central Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 14: 911-23.

- Gultie T, Hailu D, Workineh Y (2014) Age of menarche and knowledge about menstrual hygiene management among adolescent school girls in Amhara Province, Ethiopia: Implication to health care workers & school teachers. Plos One 9(9): e108644.

- Umahi Nnennaya E, Atinge S, Paul Dogara S, Joel Ubandoma R (2021) Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent school girls in Taraba state, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci 21(2): 842-51.

- Tinuola FR (2006) Analysis of some key sexual behaviour indicators among younger women in Ekiti southwest Nigeria. The Social Sciences 1(3): 171-177.

- Freeman MC, Greene LE, Dreibelbis R, Saboori S, Muga R, et al. (2011) Assessing the impact of a school-based water treatment, hygiene and sanitation programme on pupil absence in Nyanza Province, kenya: A cluster-randomized trial. Trop Med Int Health 17(3): 380-391.

- Tegegne TK, Sisay MM (2014) Menstrual hygiene management and school absenteeism among female adolescent students in Northeast Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 14: 1118.

- Belay S, Kuhlmann AKs, Wall LL (2020) Girls’ attendance at school after a menstrual hygiene intervention in northern Ethiopia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 149(3): 287-291.

- Haver J, Caruso BA, Ellis A, Sahin M, Villasenor JM, et al. (2013) WASH in schools empowers girls’ education in Masbate province and metro manila, Philippines: An assessment of menstrual hygiene management in schools.

- Sommer M, Emily VN, Murat Th D (2013) WASH in schools empowers girls’ education: Proceedings of the menstrual hygiene management in schools from the 2nd annual virtual conference; United Nations Children Fund and Columbia University, New York, USA.

- Oster E, Thornton R (2011) Menstruation, sanitary products and school attendance: Evidence from a randomized evaluation. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics.

- Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K (2008) Health behaviour and health education: Theory, research, and practice, (4th edn), Jossey-Bass.

- Sumpter C, Torondel B (2013) A systematic review of the health and social effects of menstrual hygiene management. Plos One 8(4): e62004.

- Krejcie RV, Morgan DW (1970) Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement 30(3): 607-610.

- Miiro G, Nakiyingi MJ, Nakuya K, Musoke S, Namakula J, et al. (2018) Menstrual health and school absenteeism among adolescent girls in Uganda: A feasibility study. BMC Womens Health 18(1): 4.

- Andargie FA, Tinuola FR (2025) Effects of school menstrual hygiene management, water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions on girls' empowerment, health, and educational outcomes: Lasta district, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. Plos One 20(4): e0321376.

© 2025 Fisseha Atale Andargie. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)