- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Nursing & Healthcare

Resistance and Hesitance in Establishing Pediatric Palliative Care Programs: A Brief Report from the Northeastern United States

Sean M Daley1* and Caitlin Haas2

1Department of Community and Global Health, Lehigh University, USA

2Northern California Institute for Research and Education and the San Francisco VA Health Care System, USA

*Corresponding author: Sean M Daley, Department of Community and Global Health, Lehigh University, USA

Submission: October 07, 2025;Published: November 06, 2025

ISSN: 2577-2007Volume9 Issue 4

Abstract

Pediatric Palliative Care (PPC) has been shown to relieve suffering for children with chronic and/or terminal illnesses, improve their quality of life, and help their families make decisions concerning treatments and care. However, hospitals and medical centers, including pediatric hospitals, have been slow, if not outright resistant, to establishing PPC programs. This brief report focuses on interviews with 20 individuals who had a connection to PPC as a parent, caregiver, previous PPC patient (but now an adult), clinician, or administrator to examine whether or not they believed PPC was needed in a specific region of the Northeastern United States. Interviews revealed that resistance and hesitance centered on costs, physician reimbursement, and a misunderstanding what PPC actually involves.

Introduction

It is estimated that up to 13 million children in the United States require complex medical care, defined as having physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional needs not present in a typically-developing child [1-3]. Both chronically and terminally ill children require specialized daily care, which can present a significant burden for patients, their families, and caregivers [2-4]. In particular, Children with Medically Complexity (CMC), or children with medical and/or behavioral conditions that impact two or more body systems, have high utilization rates and needs for healthcare services, with technological assistance or dependence (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2024), and their families regularly deal with issues of fragmented care, poor symptom management, financial burden, social isolation, and missed school/work [2,4]. Pediatric Palliative Care (PPC) tends to the holistic needs of the child and his/her family and caregivers by coordinating otherwise disjointed subspecialty care and developing advanced care plans that align with the goals, values, and beliefs of the patient and family [2-5]. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, health care organizations with chronic, medically-complex pediatric patients should offer an interdisciplinary PPC team to all pediatric patients [5]. The involvement of a PPC team should ideally be initiated upon diagnosis of the child, and the PPC team should remain part of the child’s care through the end of life and bereavement [5]. While the composition of a PPC team can vary greatly, PPC teams often include a coordinator, a physician, a nurse practitioner and/or a nurse, a social worker, a chaplain, and child life specialists, and they frequently provide services complementary to coordination of care and symptom management such as respite care, facilitating end of life conversations, engaging in legacy-building activities, and offering bereavement support [3-5].

Data from established PPC programs proves that PPC can be a successful part of a pediatric hospital or medical center’s programming. PPC programs invigorate the entire ecosystem surrounding a sick child. Though the field has grown significantly since its inception in the 1970s, efforts to establish PPC programs are still commonly met with fierce resistance [5,6].

Over a period of nine months in 2021 and 2022, twenty individuals who had a connection to PPC as a parent, a caregiver, a previous PPC patient (but now an adult), a healthcare provider, or a healthcare administrator were interviewed to determine whether or not they believed PPC was needed in a specific region of the Northeastern United States. The interviews focused on the benefits, obstacles, and other considerations for the development of PPC programs in the region.

As this project took place during the COVID pandemic, participants were interviewed in-person or via Zoom depending on each individual participant’s preference; Daley conducted the interviews. Semi-structured interviews were employed and the interviews ranged in length from 30 minutes to 90 minutes with the average interview lasting approximately 45 minutes. Although this project was determined to be a Quality Improvement (QI) project by the healthcare system that initiated it, standard human subjects’ interview protocols were still observed. If the interview took place in-person, participants were consented into the project via a written consent form, and if the interviews took place virtually, then they were consented into the project verbally. During the consent process-written or verbal-participants were informed that their participation was voluntary, that they could decline to answer any questions with which they were uncomfortable, and they could stop the interview at any time. In-person interviews were recorded with a digital voice recorder while virtually interviews were recorded via Zoom. Participants were given a small incentive, either a t-shirt or a ceramic mug from Daley’s academic institution. Interviews were transcribed verbatim by Daley and Haas, who also conducted a basic text analysis of the transcribed interviews which included coding the interviews and identifying the themes, and ultimately grouping the themes into categories and subcategories. Daley and Haas also identified the supporting quotes, which were deidentified to maintain the anonymity of the participants. A review of the existing literature on PPC was also conducted to understand what factors may have contributed to these themes and subthemes, and the literature appears to be in line with the themes and subthemes from the interviews.

In the end, a formal report was submitted to the healthcare system that initiated the project. The report was also shared with participants who were interested in reviewing it.

Result

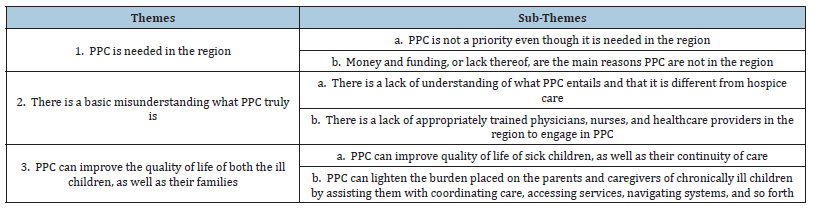

The interviews yielded three main themes, each with subthemes. Table 1 below contains the themes and subthemes.

Table 1:Themes and Sub-Themes.

Theme 1: PPC is needed in the region

The overwhelming majority of participants stated that PPC is needed in the region. One healthcare provider simply stated, “It’s kind of embarrassing that we have a children’s hospital, and we don’t have palliative care as part of that…we need to-to do more with (it), to the support the development of it.” Another healthcare provider explained, “We have to go at this (PPC) because we have a children’s hospital. I think it’s as simple as that, and that if we have a children’s hospital, it has to be a full-fledged children’s hospital.”

The mother of a child who currently utilizes PPC stated:

“It’s been well overdue…I remember having conversations with people about… ‘Why is there not hospice or palliative care…in this area?’…I think palliative care also brings about support services for families like ours because [my child] has been through eleven therapists…Eleven…there’s no one here…family after family in this area, this is one of our big complaints, that there’s no one to help our kids and our families process this and live with this…that is where palliative care can really also step in and fill that gap.”

Hospital administrators are often opposed and unwilling to allocate

resources to PPC programs [1,7]. The logistics of starting a

new PPC program and issues concerning funding, billing, and insurance,

as well as staffing, can be reasons for the opposition [1].

PPC programs are not generally sources of income for hospitals and

medical centers, which can be perceived as a drawback by administrators.

During an interview, one medical center administrator

stated:

“It’s very expensive taking care of those kids…the physicians can

bill for their time, nurses can bill for some of the time, but all of those

programs that I mentioned are being heavily philanthropically funded

through their hospital foundations…every single one of them are heavily

philanthropically funded so that they can have the full interdisciplinary

team to take care of families. To have the chaplain, to have the art therapist,

the music therapist, all those things that are not…reimbursable.”

This idea was echoed by a healthcare provider who stated, “The funding is going to be [an issue] and the reimbursement is going to be the bigger issue …For anybody to approve anything like this, they always want to know where the money’s coming from and how it’s going to sustain itself.”

While caring for medically complex and chronically ill children

is costly, it is a misconception that PPC programs are explicit financial

drains on hospitals and medical centers [1,8]. Many existing

PPC programs are self-sustaining and reduce overall costs by

shortening the length of pediatric inpatient stays [1,7]. A healthcare

provider and parent of a terminally ill child who utilizes PCC stated:

“I’ve even been told by a doctor that he’s [my son] ‘a socioeconomic

burden to society.’ So, this is why it’s really hard to get doctors to take

care of these chronically ill, disabled children; because many just don’t

care. Hospitals don’t care. It’s all about the dollar…the (palliative care)

approach is, if you can save the money by not being in the hospital, to

get the proper proactive care and preventive care, then that will save the

money in the long run…that’s my angle.”

Furthermore, the existence of PPC teams is associated with positive outcomes for other hospital staff. Sharing the burden of caring for seriously-ill children reduces the time clinicians have to spend with patients; this leads to less burnout and staff turnover [1].

Theme 2: There is a basic misunderstanding what PPC truly is

Working with children with medical complexity and/or chronic illnesses requires physical, mental, and emotional strength, as well as specific training [1,3,9-11]. Unfortunately, there is a scarcity of data about how many pediatric palliative care programs, fellowships, and residencies actually exist, which suggests adequate training may not always be available. The lack of training opportunities is potentially a limiting factor in the number of professionals trained in PPC. As one healthcare practitioner who participated in the project noted, “We’ve never had…a physician who is palliative medicine trained…you educate yourself, you go to the conferences that you can go to, to get that palliative care education, and you learn about…pain management and symptom management and… psychosocial things, but there’s nothing really formal.”

It is possible that hesitancy surrounding PPC is also strongly

embedded in Western medical culture. Medical training teaches

physicians to focus on curative, life-sustaining care [7]. It can also

encourage physicians to pursue aggressive treatments, even when

they prove futile [7]. These practices do not leave room for the possibility

that not all patients will recover; a weak point in clinical

training. The ethos practitioners internalize in medical school is

not always practical in the clinical setting. Hyper- focusing on curative

care makes healthcare providers ill-equipped to handle issues

of uncertain prognosis, especially in pediatric populations. One

healthcare provider noted that:

“There’s a lot of kids at home, and doctors don’t have open

minds…a lot of doctors…they’re not going to talk about hospice, which

I get…But palliative care? Be open to the fact that somebody could go

in and just start getting to meet these children and their families so a

relationship could be started…and be open to the fact that maybe, even

though you think you could get that child to live for ten more years,

maybe sometimes parents say, ‘You know what, enough is enough,’ or

maybe get to go in early enough, children will make that decision and

say, ‘Enough is enough.’ I’ve had kids say to me, ‘I don’t want any more.

I just want to be a normal kid.’”

Additionally, healthcare professionals of all types are often uncomfortable

with PPC because they do not usually receive proper

training on how to handle cases where children are chronically or

terminally ill. As a result of this, providers may fail to introduce and

advocate for palliative care [7,12]. Physicians can hold misconceptions

that inform their views on PPC [2,9]. A physician may view

the introduction of a PPC team as a challenge to his/her own skills

as a provider when in reality, PPC teams work in tandem with the

patient’s primary care physician [1]. One parent explained:

“They [people who do not have chronically ill children] don’t

understand the…care…I think there is a need for it (PPC)…Last

November was the first time I got three specialists scheduled for one

day…ninety-five pounds in and out of a car, with a wheelchair and

things…I don’t know that they understand that you’re doing this for

eighteen years…I think if there was palliative care, there would be some

understanding of you do this in and out, all day, every day.”

Physicians may also draw a false equivalency between referring

a pediatric patient to palliative care and giving up on him/her

[1,7]. Because palliative care is often equated with hospice care,

even in clinical settings, healthcare providers can misjudge when

their patients are ready for palliative care [3,12]. However, palliative

care and hospice, while related, are distinct services. Palliative

care encompasses comfort, the reduction of suffering, and continuity

of care. Unlike in the adult sphere, children can receive curative,

life-sustaining care and comfort care simultaneously [1,3]. One

healthcare provider who is now an administrator explained:

“Hospice ties into palliative care. Palliative care doesn’t always lead

to hospice. But some of the concepts are the same, about taking care of

the entire family and recognizing kind of the whole impact of a chronic

illness or a life-limiting illness on the patient and the family and seeing

beyond…we see it now…if you don’t have a good PCP, and you have

five specialists, and they’re all working independently, nobody’s overseeing

the whole thing or even appreciating the whole package that the

family and patient are going through. So…any time you can get someone

with a specialty or an interest or a focus on putting the whole picture

together, I think you minimize a lot of problems. I think you increase

quality of life and hopefully reduce symptoms and interactions…things

that maybe that individual and all those individual specialties don’t see

or maybe can’t see or don’t have time to see.”

Physicians who are, themselves, apprehensive about palliative

care can perceive it as being something that is stressful and anxiety

producing for families as well [7,12]. Rather than processing the

difficult and negative feelings that arise when treating chronically

or terminally ill children, providers often avoid these feelings, with

the rationale of wanting to protect patients and families from the reality

that the child is seriously ill [7]. When providers fail to accept

that their pediatric patients could benefit from PPC, while well-intentioned,

they can deprive patients and families of the benefits of

palliative care and can actually increase incidences of depression

and anxiety. A healthcare provider and administrator stated:

“I think both health care professionals and families and patients

need to understand what the definition of palliative care is and what the

goal is…we know that this disease isn’t going away. We know that this

causes all kinds of burden to the patients and the families, and it’s complex,

and that’s the specialty of a palliative care team, is to deal - when

it gets to that level, that it’s complex, and it’s causing, you know, maybe

it’s to prevent…additional stresses and additional worries, and again,

improving their quality of life.”

Theme 3: PPC can improve the quality of life of the patients, as well as their families

As previously noted, PPC is associated with numerous positive outcomes, including integrated subspecialty care, improved pain management, reduced hospital stay duration, and fewer hospital admissions [5,10,13,14]. Properly addressing the child’s physical symptoms is also often associated with improved mental health and increased patient compliance [3,13,14]. Some studies also found children who had PPC teams even lived longer [1]. One parent of a chronically ill child who is often hospitalized and has a palliative care team in the hospital stated, “He has a huge child life [program]…beyond that they have…coffee houses for parents where they bring in live music, and they have… all kinds of parties… you could live in the hospital and still be doing lot…you could live in the hospital, and your kids could still experience really great stuff.”

With PPC, families can be relieved of many of the burdens of

caring for a child who has a serious illness and receive support in

the event the child passes [14]. Families generally value the clear

communication PPC teams provide because it promotes trust, informs

medical decision-making, and bolsters patient’s understanding

of their own condition [12,14]. PPC teams can also work with

families to create care plans that honor the values of the family [3]

(Thompkins et al., 2021). Early understanding of prognosis as well

as understanding the child’s goals for their life and death promote

better adjustment for parents and families following the death of a

child [14]. The work the PPC team does allows for parents to spend

more time with their child [14]. One healthcare provider noted:

“I feel like a pediatric palliative care provider can really…help the

family discuss what the goals for their child is and then really help support

the family in…making decisions that…aren’t…life or death, but

do definitely contribute to…the child’s family’s…wellbeing and I hate

“quality of life,” but, a quality of life-type thing. So… I feel like that really

does deserve kind of a separate and dedicated visit to discuss…what the

goals of the family’s care is and then…what to expect moving forward

for a lot of these patients (Healthcare provider)

Conclusion

PPC as a subspecialty has blossomed over the last few decades as the benefits of it for patients, families, and providers have been recognized [5,6]. However, there are still several common barriers to starting PPC programs [5,6]. These include lack of resources and misconceptions about what PPC is [1,7,12]. Medical culture, which is too often fixated on curative care, often leads healthcare professionals to be uncomfortable discussing death [7]. Mistaken understandings about the relationship between PPC and hospice can lead healthcare professionals to believe that a PPC referral is equivalent to one for hospice [7]. PPC can, however, be utilized simultaneously with curative care and lead to better outcomes for patients and their families [1,3]..

The benefits attributed to PPC programs reveal that many of the fears administrators and providers have about PPC are unfounded [5,10,13,14]. The literature suggests most often the issue has to do with physician and administrator avoidance of uncomfortable topics and a misunderstanding of PPC. A lack of knowledge and misunderstanding about PPC fosters disconcertment with it; providers perceive PPC as being antithetical to their standard practice. This bias appears to originate early in their training and then translates into a focus on life-sustaining care that permeates larger healthcare institutions and stalls PPC initiatives.

While the authors do believe this project was successful and that it can be a positive addition to the conversation concerning pediatric palliative care, this project does have its limitations. Due to its small sample size and its limited geographical focus, the project is not highly generalizable.

Funding

This project was funded by the Office of the Vice President and Associate Provost for Research and Graduate Studies at Lehigh University, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, USA.

References

- Friedrichsdorf SJ, Bruera E (2018) Delivering pediatric palliative care: From denial, palliphobia, pallilalia to palliactive. Children 5(9): 120.

- Johnston EE, Currie ER, Chen Y, Kent EE, Ornstein KA, et al. (2020) Palliative care knowledge and characteristics in caregivers of chronically ill children. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing 22(6): 456-464.

- Moresco B, Moore D (2021) Pediatric palliative care. Hospital Practice 49(Suppl 1): 422-430.

- Norris S, Minkowitz S, Scharbach K (2019) Pediatric palliative care. Primary Care 46(3): 461-473.

- Rogers MM, Friebert S, Williams CSP, Humphrey L, Thienprayoon R, et al. (2021) Pediatric palliative care programs in US Hospitals. Pediatrics 148(1): e2020021634.

- Miller EG, Weaver MS, Ragsdale L, Hills T, Humphrey L, et al. (2021) Lessons learned: Identifying items felt to be critical to leading a pediatric palliative care program in the current era of program development. Journal of Palliative Medicine 24(1): 40-45.

- Laronne A, Granek L, Wiener L, Feder-Bubis P, Golan H (2021) Organizational and individual barriers and facilitators to the integration of pediatric palliative care for children: A grounded theory study. Palliative Medicine 35(8): 1612-1624.

- Goldhagen J, Fafard M, Komatz K, Eason T, Livingood WC (2016) Erratum to: Community-Based pediatric palliative care for health related quality of life, hospital utilization and costs lessons learned from a pilot study. BMC Palliative Care 15(1): 82.

- Toce S, Collins MA (2003) The footprints model of pediatric palliative care. Journal of Palliative Medicine 6(6): 989-1000.

- Akard TF, Hendricks-Ferguson VL, Gilmer MJ (2019) Pediatric palliative care nursing. Annals of Palliative Medicine 8(Suppl 1): S39-S48.

- Bogetz JF, Root MC, Purser L, Torkildson C (2019) Comparing health care provider-perceived barriers to pediatric palliative care fifteen years ago and today. Journal of Palliative Medicine 22(2): 145-151.

- Levine DR, Mandrell BN, Sykes A, Pritchard M, Gibson D, et al. (2017) Patients’ and parents’ needs, attitudes, and Perceptions about early palliative care integration in pediatric oncology. JAMA Oncology 3(9): 1214-1220.

- Ward-Smith P, Linn JB, Korphage RM, Christenson K, Hutto CJ, et al. (2007) Development of a pediatric palliative care team. Journal of Pediatric Health Care 21(4): 245-249.

- Snaman J, McCarthy S, Wiener L, Wolfe J (2020) Pediatric palliative care in oncology. Journal of Clinical Oncology 38(9): 954-962.

© 2025 Sean M Daley. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)