- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Nursing & Healthcare

Comparing the Impact of vSim and Gaumard Simulations on Nursing Students’ Satisfaction and Self-Confidence

Joy A Bliss*

Assistant Professor of Nursing, Simulationist Obstetrics and Pediatrics, Faculty of Nursing, Hawaii Pacific University, USA

*Corresponding author: Joy A Bliss, Assistant Professor of Nursing, Simulationist Obstetrics and Pediatrics, Faculty of Nursing, Hawaii Pacific University, USA

Submission: May 30, 2025;Published: August 06, 2025

ISSN: 2577-2007Volume9 Issue 3

Abstract

This study compares the effectiveness of two simulation methods in nursing education: vSim (virtual simulation) and Gaumard (high-fidelity simulation). The focus is on measuring nursing students’ satisfaction and self-confidence after participating in both types of simulations. Data were collected from a cohort of 100 nursing students across various clinical scenarios, and the results indicate differences in satisfaction and self-confidence based on the simulation type. The findings suggest that high-fidelity simulations (Gaumard) may better enhance nursing students’ clinical preparedness and self-confidence.

Keywords: Virtual simulation; High-Fidelity simulation; Nursing education; Satisfaction; Self-Confidence; Clinical preparedness; Simulation-Based learning

Introduction

Simulation-based learning has become a cornerstone in nursing education, offering students the opportunity to practice clinical skills in a controlled, risk-free environment. As healthcare education evolves, simulation provides an essential tool for developing critical thinking, clinical decision-making, and hands-on skills without the risk of harm to patients [1,2]. The integration of simulation into nursing curricula has been shown to improve student performance, enhance knowledge retention, and increase clinical preparedness [3,4].

The advancements in simulation technologies have led to the development of two prominent methods: virtual simulation (vSim) and high-fidelity simulation (Gaumard). Virtual simulation platforms like vSim offer students the ability to engage in interactive, computer-based scenarios that mimic real-life clinical experiences [3]. These platforms provide flexibility and allow students to practice at their own pace, making them accessible for foundational knowledge and repetitive learning [5]. However, virtual simulations may lack the immersive, hands-on qualities needed for more complex skill development [6].

On the other hand, high-fidelity simulations, such as those provided by Gaumard mannequins, offer a more immersive learning environment by simulating real-time physiological responses and requiring students to engage in hands-on activities, such as assessments and interventions [7]. These simulations offer immediate feedback, enhancing students’ learning experiences and contributing to greater satisfaction and self-confidence in clinical tasks [8]. High-fidelity simulations are particularly beneficial for tasks that require physical manipulation and critical decision-making, such as managing complex medical conditions [4].

This study compares the effectiveness of these two simulation methods-vSim (virtual simulation) and Gaumard (high fidelity simulation) modalities-on undergraduate nursing students’ satisfaction and self-confidence levels following participation in the two modalities. Understanding the impact of each simulation type on these outcomes is crucial for optimizing nursing curricula to better prepare students for clinical practice [9]. By exploring these differences, this research aims to provide insights into the role that simulation plays in shaping nursing students’ clinical readiness and overall learning experience.

The objective of this study was to compare nursing students’ satisfaction and self-confidence after participating in vSim and Gaumard simulations. The aim was to determine which simulation method, vSim or Gaumard, more effectively contributes to enhancing students’ satisfaction and self-confidence for clinical readiness and overall learning experience.

Methods

This study was conducted at Hawaii Pacific University (HPU) in Honolulu, Hawaii, during the Fall 2024 semester. A cohort of 100 undergraduate nursing students from the Pediatric and Obstetrical nursing courses participated in the study. The cohort was divided into two groups: 50 students from the Pediatric nursing program and 50 from the Obstetrical nursing program. Each student participated in both vSim and Gaumard simulations in a randomized crossover design to control order bias. The simulations were conducted in random order, ensuring that each student experienced both types of simulations at different stages of their clinical courses. Participation was voluntary, and all students provided informed consent prior to the start of the study. Ethical approval for the study protocol was granted by the HPU Institutional Review Board (IRB) prior to conducting the study. Satisfaction and self-confidence were measured using the 13-question Student Satisfaction and Self-Confidence in Learning Scale (SCLS), a well-established tool in nursing education. Data analysis was conducted using descriptive statistics, paired t-tests were used to analyze differences in scores between the two simulations methods. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to examine the relationship between satisfaction and self-confidence. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Conceptual Framework

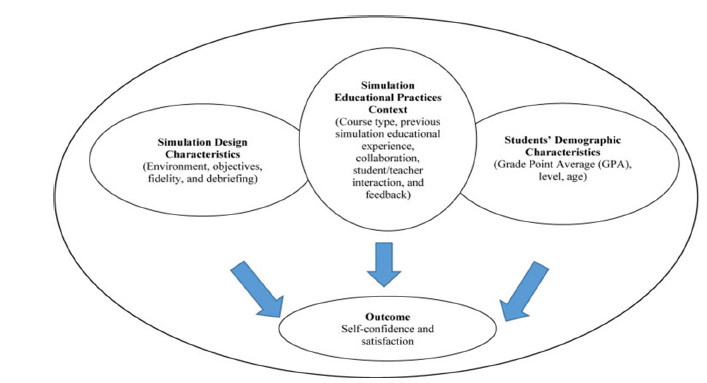

This study was guided by the National League for Nursing (NLN)/Jeffries Simulation Framework (Figure 1). This framework was first published by Jeffries in 2005 and later adapted in 2010 to support simulation experiences for students in nursing education. The framework was selected for this study because it provides a comprehensive understanding of the design, characteristics, application, and evaluation of simulation activities in nursing education [7]. The framework identifies five key constructs: teacher, student, simulation design characteristics, educational practices context, and outcomes [10]. The interaction between these constructions influences the overall simulation outcomes, such as satisfaction and self-confidence, which were the focus of this study.

Fgure 1:Adaptation of the NLN/Jeffries simulation framework.

Result

Paired t-tests revealed that Gaumard simulations significantly improved both satisfaction and self-confidence compared to vSim. Satisfaction scores for Gaumard (M=4.6, SD=0.5) were significantly higher than for vSim (M=4.1, SD=0.6), t (99) =2.35, p=.03. Similarly, self-confidence scores for Gaumard (M=4.7, SD=0.4) were higher than for vSim (M=4.2, SD=0.5), t (99) =2.65, p=.01. The reliability of the SCLS scale was acceptable, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .87 for this sample.

Overall Satisfaction and Self-Confidence Scores

The results revealed that Gaumard simulations resulted in higher satisfaction and self-confidence scores compared to vSim. The average satisfaction score for Gaumard was 4.6/5, while vSim scored 4.1/5. Similarly, the self-confidence score for Gaumard was 4.7/5, compared to 4.2/5 for vSim. These differences were statistically significant (satisfaction: t=2.35, p=0.03; selfconfidence: t=2.65, p=0.01).

Comparison between Pediatric and Obstetrical Nursing Students

Both Pediatric and Obstetrical nursing students showed higher satisfaction and self-confidence with Gaumard simulations. Pediatric students reported a more significant difference in scores between the two simulations, with a mean satisfaction score of 4.7 for Gaumard versus 4.2 for vSim, and a self-confidence score of 4.8 for Gaumard versus 4.3 for vSim. Obstetrical students also demonstrated higher satisfaction and self-confidence with Gaumard, but the differences were less pronounced compared to the Pediatric group.

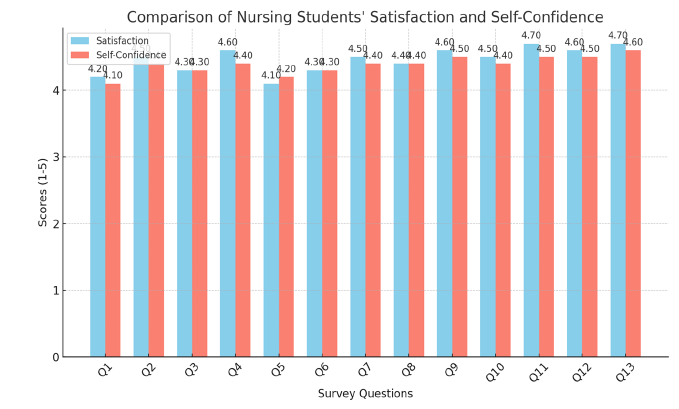

This chart displays both satisfaction (in sky blue) and selfconfidence (in salmon) scores for each of the 13 survey questions, with a 5-point Likert scale rating. As shown, satisfaction scores generally exceeded self-confidence scores. The trend indicates that students felt more satisfied with the simulation activities than confident in their ability to apply the learned skills in real-world clinical settings (Figure 2).

Fgure 2:Comparison of nursing students’ satisfaction and self-confidence across 13 survey questions.

Discussion

The study’s results indicate that Gaumard simulations are more effective than vSim in improving nursing students’ satisfaction and self-confidence. Gaumard’s, hands-on, immersive nature likely contributes to greater student engagement, real-time feedback, and higher confidence in clinical skills. The findings align with previous studies that highlight the benefits of high-fidelity simulations in promoting clinical preparedness [4,9]. These factors are critical for building students’ confidence in their clinical skills, as they can perform tasks such as assessments, interventions, and clinical decision-making in real-time [7].

Possible confounding variables, such as prior clinical exposure and familiarity with digital platforms, may have influenced student’s perceptions and outcomes. Students who are more comfortable with virtual platforms might report higher satisfaction with vSim. To mitigate these biases, future studies could assess the impact of students’ prior exposure to simulations or their comfort levels with different technologies. More, over, the timing of exposure to each simulation method could influence outcomes, as students may become more confident with repeated exposure to either type,

The increased satisfaction and self-confidence reported by students after Gaumard simulations are consistent with other studies that have highlighted the advantages of high-fidelity simulation in nursing education. High-fidelity simulations have been shown to improve critical thinking, clinical skills, and readiness for real-world practice [4,9]. The immersive nature of these simulations enhances students’ ability to perform under pressure and engage in complex clinical tasks, which are essential for developing clinical competence.

However, vSim also plays an important role in nursing education, particularly in foundational knowledge and theoretical learning. Virtual simulations provide students with the flexibility to practice various scenarios repeatedly and at their own pace, making them an effective tool for learning and reinforcing basic concepts [5]. Despite this, the lack of physical interaction with a mannequin and the immediate, tactile feedback that high-fidelity simulations offer could explain the lower satisfaction and self-confidence scores observed in the vSim group. Virtual simulations may also not be able to replicate the stress and urgency associated with real clinical environments, which could limit students’ preparedness for highstakes clinical situations [6].

Moreover, the combination of both vSim and Gaumard in nursing curricula could provide a balanced approach to education, where vSim can be used for theoretical practice and Gaumard can be utilized for skill development and complex scenario-based learning. This dual approach could enhance the overall learning experience by addressing both the cognitive and psychomotor domains of nursing education [2]. Such a blended approach aligns with the findings of other studies that have shown positive results when integrating both virtual and high-fidelity simulations into nursing programs [11,12].

Although this study provides valuable insights into the comparative effectiveness of vSim and Gaumard simulations, it has some limitations. The sample size was limited to nursing students from a single university, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future studies should include a more diverse sample from multiple institutions to determine if these results are consistent across different nursing programs [13-15]. Additionally, longterm studies that track the clinical performance of students after participating in these simulation types would provide valuable information regarding the sustained impact of these methods on clinical competence and patient care outcomes [9].

The NLN/Jeffries Simulation Framework guided this study, underscoring the importance of simulation design and the learning environment in shaping education outcomes [7]. This framework highlights the interaction between student engagement, feedback, and the realism of the simulation, all of which were integral to the success of Gaumard simulations. Incorporating both simulation methods into nursing curricula can create a balanced learning experience. Virtual simulations like vSim are valuable repetitive, theoretical practice, while Gaumard simulations provide real-world clinical skill development and decision -making opportunities. A blended approach utilizing both methods could offer a more wellrounded educational framework [2].

Conclusion

Gaumard simulations significantly enhance nursing students’ satisfaction and self-confidence compared to vSim. These results highlight the need for high-fidelity simulations into the nursing curricula to better prepare students for clinical practice and to provide a more comprehensive and effective learning framework for nursing students. Nursing Educators should consider a blended approach, incorporating both vSim for foundational knowledge and Gaumard for hands-on, immersive experiences. Future research should explore long term effects on clinical performance and investigate strategies to optimize the integration of simulationbased learning in nursing curricula.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Dr. James Davis at the University of Hawaiʻi John A. Burns School of Medicine for his contribution to the analysis of the statistical data for this study under the PIKO grant awarded to Dr. Bliss.

The PIKO Program is supported by grant number #U54GM138062 from the National Institute for General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and its contents are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIGMS or NIH.

References

- Cantrell MA, Franklin A, Leighton K, Carlson A (2017) The evidence in simulation-based learning experiences in nursing education and practice: An umbrella review. Clinical Simulation in Nursing 13(12): 634-667.

- Kaddoura M (2016) Simulation in nursing education: A review of the literature. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice 6(7): 24-35.

- Foronda CL, Swoboda SM, Henry MN, Kamau E, Sullivan N, et al. (2018) Student preferences and perceptions of learning from vSIM for nursing™. Nurse Education in Practice 33: 27-32.

- Chen Y, Chou H (2022) High-fidelity simulation in undergraduate nursing education: A meta-analysis. Nurse Education Today 111: 105291.

- Verkuyl M, Hughes M (2019) Virtual gaming simulation in nursing education: A mixed-methods study. Clinical Simulation in Nursing 29: 9-14.

- Burns H, O'Donnell J, Artman J (2010) High-fidelity simulation in teaching problem solving to 1st-year nursing students: A novel use of the nursing process. Clinical Simulation in Nursing 6(3): e87-e95.

- Groom JA, Henderson D, Sittner BJ (2014) NLN/Jeffries simulation framework state of the science project: Simulation design characteristics. Clinical Simulation in Nursing 10(7): 337-344.

- Davis D, Finley D (2014) The learning effectiveness of high-fidelity simulation in nursing education. Journal of Nursing Research 22(2): 120-126.

- Khasawneh EA, Arulappan J, Natarajan J, Isac C (2021) Efficacy of simulation using NLN/Jeffries nursing education simulation framework on satisfaction and self-confidence of undergraduate nursing students in a Middle-Eastern country. SAGE Open Nurs 7: 1-10.

- Ravert PL, McAfooes J (2014) The NLN/Jeffries simulation framework: State of the science summary. Clinical Simulation in Nursing 10(7): 335-336.

- Alharbi AA, Alqahtani MA (2024) The effectiveness of Simulation-Based Learning (SBL) on students' knowledge and skills in nursing programs: A systematic review. BMC Medical Education 24(1): 1099.

- Tawalbeh LI (2020) Effect of simulation modules on Jordanian nursing student knowledge and confidence in performing critical care skills: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences 13(4): 100242.

- Alsadi M, Oweidat I, Khrais H, Tubaishat A, Nashwan AJ (2023) Satisfaction and self-confidence among nursing students with simulation learning during COVID-19. BMC Nursing 22(1): 327.

- Kaliyaperumal R, Raman V, Kannan LA, Ali MD (2021) Satisfaction and self-confidence of nursing students with simulation teaching. International Journal of Health Sciences and Research 11(2): 46-50.

- Vangone I, Arrigoni C, Magon A, Conte G, Russo S, et al. (2024) The efficacy of high-fidelity simulation on knowledge and performance in undergraduate nursing students: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Nurse Education Today 139: 106231.

© 2025 Joy A Bliss. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)