- Submissions

Full Text

Biodiversity Online J

A Reflection on Mount Tsukuba Visit: A Journey of Elevation, Ethics, and Ecology

Chee Kong Yap*

Department of Biology, University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia

*Corresponding author:Chee Kong Yap, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, University Putra Malaysia, 43400 UPM Serdang, Malaysia

Submission: June 24, 2025; Published: July 28, 2025

ISSN 2637-7082Volume5 Issue 4

Abstract

This reflection captures a deeply personal and transformative experience during my academic sabbatical in Japan in November 2017. Among various memorable encounters, the visit to Mount Tsukuba stands out for its blend of physical journey, spiritual serenity, and symbolic significance. Despite its modest elevation of approximately 877 meters-far less than Malaysia’s Genting Highlands (1800 meters)- Mount Tsukuba offered a uniquely sacred ambiance shaped by autumn foliage, cultural elements, and introspective walkways. This reflective article narrates my walk with my family through rock stairs, past shrines, and along a colorful path toward the cable car station, all culminating in a symbolic ascension that resonates with ecological principles and environmental ethics. Drawing from this lived experience and supported by studies on mountain ecology, agro-ethics, and conservation, I connect personal aging, spiritual grounding, and the rise and fall patterns of nature and life itself to the ecological Shelford Law of Tolerance. This reflection articulates the emotional landscape of walking up and down-not only the mountain, but the metaphor of life’s journey.

Keywords: Mount Tsukuba; Personal reflection; Environmental ethics; Autumn foliage; Sacred nature

Introduction

Figure 1:A tranquil scene near the bus stop leading to Mount Tsukuba’s cable car station, showing the pathway lined with stone features, autumn foliage, and a traditional shrine. This sacred stretch marks the beginning of the journey, offering spiritual ambiance and a symbolic transition into nature, on the 24th June 2025.

In November 2017, I had the rare chance to slow down and reflect deeply. Among all destinations visited during my academic visit in Japan, Mount Tsukuba remains the most vivid in memory. Though modest in height at 877 meters, the mountain became a powerful symbol of introspection and spiritual elevation. Accompanied by family (my wife and two daughters), I set foot on a journey that blended ecological curiosity with emotional resonance.

The experience began at the base of the mountain, where a humble stone shrine was nestled beside the path (Figure 1). This initial sight grounded me in a sense of place-one that was sacred, quiet, and deeply connected to both cultural reverence and natural presence. In that moment, I felt the merging of landscape and spiritual symbolism, echoing the concept of mountains as socio-ecological spaces of cultural identity [1].

Environmental ethics: The sacredness of the pathway

Walking the stone trail toward the cable car station was not just physical-it was ethical. As shown in Figure 2, the steps were steep and winding, flanked by trees bathed in red and gold leaves. There were simple shops, including one selling soft-serve ice cream, yet none of them disrupted the harmony of the space. The balance between human livelihood and natural integrity was striking. This observed harmony aligns with the ethical framework of mountain agro-ethics, which advocates moral integration between human activity and environmental stewardship, as demonstrated in Chinese mountain regions [2]. Here in Japan, the respectful coexistence of nature and culture on Mount Tsukuba exemplified a lived environmental ethic-where the forest was not something to conquer, but something to belong to.

Figure 2:Ascending on foot via stone stairs through vibrant autumn scenery, flanked by local stores selling traditional items and seasonal treats. The effort required in this segment reflects both physical exertion and mental readiness, embodying the metaphor of life’s uphill journey.

Ecological ethnic: Autumn’s lessons and the limits of life

Figure 3:The cable car entrance at Mount Tsukuba, capturing the structured layout of the station. This point of transition-from physical walk to mechanical lift-symbolizes the assistance and tools we sometimes need in life’s ascensions.

As the path steepened, we reached the cable car station (Figure 3), a small hub of transition where elevation gained new meaning. The cable car ride (Figure 4) ascended slowly through brilliant canopies of orange and red. As I sat with my daughters, I felt both awe and gratitude. Yet, years later, at 52 and facing Plantar fasciitis, I now see that even simple hikes are no longer easy. This change mirrors the ecological principle of tolerance-the limits within which species and individuals can thrive. Mountains often serve as natural laboratories for ecological study. Elevation gradients, such as those at Mount Tsukuba, shape species distribution, functional traits, and biodiversity [3,4]. Studies have shown that including elevation as a predictor in species distribution models improves accuracy, especially in highland zones [5]. Just as the vegetation shifts with elevation, so too do our physical and emotional capacities. Beyond its scenic appeal, Mount Tsukuba presents an ecological complexity that extends into climatic, biological, and even pharmaceutical domains. The mountain is known for its distinctive thermal belt-a zone of warmer air occurring on mid-slopes due to cold air drainage at night-which creates microclimatic variations that influence both flora and fauna distribution [6]. This climatic layering supports ecological niches that sustain diverse mammalian species, as evidenced by camera-trap monitoring studies documenting a rich variety of terrestrial mammals, including raccoon dogs and sika deer [7]. Intriguingly, Mount Tsukuba is also tied to scientific discovery, as soil samples collected from this mountain led to the isolation of Streptomyces tsukubaensis, the bacterium responsible for producing tacrolimus, a breakthrough immunosuppressive drug [8]. These scientific and ecological findings highlight that Mount Tsukuba is not only a site of personal reflection and natural beauty but also a living laboratory, where climate, biodiversity, and biomedicine intersect in remarkable ways. Moreover, Mount Tsukuba is not immune to environmental pressures. Atmospheric measurements have revealed acidic pollutants even in this seemingly pristine region [9]. This highlights the broader vulnerability of mountain ecosystems to anthropogenic stress, reinforcing the need for integrated environmental ethics and conservation.

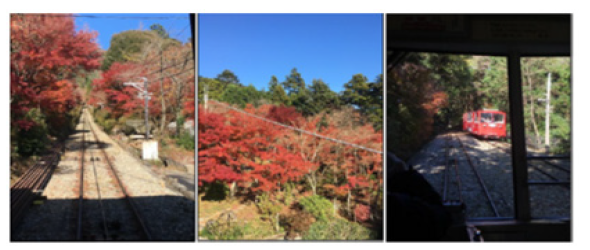

Figure 4:Scenes from inside the cable car while ascending Mount Tsukuba, revealing stunning views of autumn

canopies and a glimpse of another descending car. The imagery highlights elevation, perspective, and the dual flow

of upward and downward life experiences.

Note:

A frontal view along the railway tracks of the Tsukuba Cable Car, flanked on both sides by vivid red and orange

foliage. The foliage is dense and radiant, characteristic of peak autumn. The primary tree seen here is the Japanese

maple (Acer palmatum), known for its brilliant red leaves during the fall.

b) Center photo: A landscape shot reveals a forested slope dominated by Acer palmatum, whose crimson

foliage stands out dramatically against the backdrop of evergreen conifers, likely Cryptomeria japonica (Japanese

cedar) or Chamaecyparis obtusa (Hinoki cypress). The color contrast exemplifies the diverse mixed temperate forest

ecosystem of Mount Tsukuba.

c) Right photo: Taken from inside the ascending cable car, this photo captures a descending red car moving

toward the station, again framed by autumn foliage. The Japanese maples are dominant, while patches of Quercus

serrata (konara oak) and Fagus crenata (Japanese beech) might also be present among the understory, displaying

muted yellows and browns.

Words for digestion: Standing on the peak, seeing within

Arriving at the summit, we were greeted by expansive views of the Kanto Plain. As seen in Figure 5, the landscape stretched endlessly-on one side barren and muted, on the other green and thriving. A circular observation deck provided a panoramic vantage point, and a commemorative stone slab in Kanji marked the peak with silent dignity. Standing there, I did not feel triumphant, but contemplative. The feeling was not one of conquering a height, but of arriving at a place within. Mount Tsukuba’s summit, like many others, offers a symbolic space where environmental beauty and spiritual insight converge. The experience echoed the significance of ecosystem service value assessments, which emphasize not only ecological function but cultural and psychological enrichment [10]. Comparative studies have shown that elevation gradients in other mountain ranges-such as the Fu-Niu and Qinling mountains-reveal similar biodiversity patterns and human-nature interactions that are critical for conservation planning [2,4]. These insights can guide sustainable management efforts for Mount Tsukuba, preserving its ecological role and emotional resonance for future visitors.

Figure 5:Panoramic views from the summit of Mount Tsukuba. The upper panels show expansive landscapes, while the lower panels capture the observation house and a commemorative stone slab, symbolizing arrival, reflection, and spiritual fulfillment at the peak.

Descent: The rhythm of letting go

Descending via the cable car (Figure 6) marked a gentle ending to a profound journey. As the vibrant foliage passed by once more, the emotions shifted from curiosity to reflection. This final phase of the trip was no longer about effort or destination-but about appreciation. The same trees, the same slopes, now appeared more familiar, as if we were being gently returned. Descending reminded me that in life, the descent is not necessarily decline-it can be a return, a reconnection, a soft landing. In many mountainous socio-ecological systems, including those in the Andes and East Africa, community-based conservation values such as reciprocity, reverence, and interdependence are emphasized [11]. These values echoed through my thoughts as we floated downward. The mountain had shared something profound with us-not just a view, but a mirror.

Figure 6:Moments during the cable car descent from Mount Tsukuba, passing through tunnels of orange and

red foliage. The downward journey evokes reflection on impermanence, decline, and the graceful return after

experiencing the heights.

Note:

a) Left photo: This image shows a view down the tracks of the Tsukuba Cable Car surrounded predominantly

by evergreen coniferous trees. The dominant species here appears to be Cryptomeria japonica (Japanese cedar),

forming a dense green canopy. The absence of autumn coloration in this section reflects either a lower deciduous

density or a cooler, shaded microclimate where color change is delayed.

b) Center photo: This striking photograph captures a transition zone with a tunnel-like view of the railway

flanked by vibrant red-leaved Acer palmatum (Japanese maple). The image reflects a peak kōyō season, showcasing

the dramatic change in leaf pigmentation driven by decreasing temperatures and light. The evergreen trees-likely

Cryptomeria japonica and Chamaecyparis obtusa-stand as dark vertical backdrops to the flaming red and gold

maples, enhancing the visual depth and species contrast.

c) Right photo: A more intimate, ground-level scene of a forest trail illuminated by golden light and

surrounded by Acer palmatum in full autumn display. The meandering path and dappled shadows create a

contemplative atmosphere, emphasizing the immersive quality of seasonal forest aesthetics in Mount Tsukuba.

Some Quercus serrata (konara oak) may be present, contributing to the orange-brown hues.

Conclusion: Returning from the Peak with a Fuller Heart

Mount Tsukuba was not the tallest mountain I have ever climbed, but it gave me the highest view I have ever felt. It reminded me that spiritual elevation has little to do with altitude, and everything to do with awareness. What I experienced on that mountain, walking slowly with my wife and daughters, is something I continue to revisit-especially now, when my body reminds me of its own limits. The memories held within each stone, each stair, and each fallen leaf are more than visuals-they are teachings. They tell me to slow down. To be grateful. To recognize that beauty exists in both ascent and descent, in both strength and vulnerability. I learned that we do not always need to reach the summit by foot. Sometimes, we are carried by cable cars, or by love, or by memory. And that is enough. As I look back, I do not only see the mountain-I see the people I was with, the silence we shared, and the thoughts that arose in stillness. Mount Tsukuba was not only a journey up and down a hill-it was a journey through the seasons of my own life. And though my feet may not carry me there again, my heart remains on that sacred trail, where nature, time, and soul once walked together.

References

- Payne D, Snethlage M, Geschke J, Spehn EM, Fischer M (2020) Nature and people in the Andes, East African mountains, European alps, and hindu kush himalaya: Current research and future directions. Mountain Research and Development 40(2): A1-A14.

- Wang JQ (2024) The ethnonational symbols of “Mountain-River” in contemporary Chinese discourse. Cogent Arts & Humanities 11(1): 2419144.

- Liao BH, Ding SY, Hu N, Gu YF, Lu XL, et al. (2011) Dynamics of environmental gradients on plant functional groups composition on the Northern slope of the Fu Niu mountain nature reserve. African Journal of Biotechnology 10(82): 18939-18947.

- Zhong JJ, Chen J, Chen Q, Ji LT, Kang B (2019) Quantitative classification of MRT, CCA ordination, and species diversity along elevation gradients of a natural secondary forest in the Qinling mountains. Acta Ecologica Sinica 39(1): 277-285.

- Oke OA, Thompson KA (2015) Distribution models for mountain plant species: The value of elevation. Ecological Modelling 301: 72-77.

- Ueda H, Hori ME, Nohara D (2003) Observational study of the thermal belt on the slope of Mt. Tsukuba. Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan 81(5): 1283-1288.

- Yasuda M (2004) Monitoring diversity and abundance of mammals with camera traps: A case study on Mount Tsukuba, central Japan. Mammal Study 29(1): 37-46.

- Ng W, Ikeda S (2009) Mount Tsukuba and the origin of tacrolimus. Archives of Dermatology 145(3): 284.

- Watanabe M, Takamatsu T, Koshikawa MK, Sakamoto K, Inubushi K (2006) Atmospheric acidic pollutants at Mt. Tsukuba, Japan, determined using a portable filter pack sampler. Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan 79(9): 1407-1409.

- Jiang DD, Yang F, Ma W, Li H, Zhang L, et al. (2022) Evolution and scenario prediction of ecosystem service value in Dalou mountain area. Research of Environmental Sciences 35(7): 1670-1680.

- Gupta H, Nishi M, Gasparatos A (2022) Community-based responses for tackling environmental and socio-economic change and impacts in mountain social-ecological systems. Ambio 51(5): 1123-1142.

© 2025 Chee Kong Yap*. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)