- Submissions

Full Text

Biodiversity Online J

Threats to the Effectiveness of Brazil’s National Protected Areas System

Machado RAS*

Department of Human Sciences and Philosophy, State University of Feira de Santana, Brazil

*Corresponding author:Ricardo Augusto Souza Machado, State University of Feira de Santana, Brazil

Submission: September 01, 2022; Published: May 03, 2023

ISSN 2637-7082Volume3 Issue4

Abstract

This paper approaches the brazilian system of protected areas, highlighting the distribution of these areas among the major biomes and the composition regarding the type of unit: Integral Protection or Sustainable Use. It also highlights the prevalence of a category of protected area called Environmental Protection Area-EPA, which accounts for about 30% of protected areas in Brazil. In practice, the EPA have greater economic than biological importance, being highly vulnerable and considered inefficient for a system of protected areas.

Introduction

The Brazilian System of Protected Areas has its origins in the late 1970s, based on the preliminary document of the IUCN Parks and Protected Areas Commission, on the works of Thelen & Miller implemented in 1976 and on studies in Priority Nature Conservation in the Amazon [1]. It culminated with the federal law that established the national system in the 2000s. Of the 33 units existing in 1970 [2], in 2020 the country surpassed the mark of 2,300 protected areas, according to data released by the WWF [3] obtained from the national registry of the Ministry of the Environment. Protected areas currently cover more than 1.6 million square kilometers of the national territory. Despite being a very expressive number, there is an imbalance in relation to the type of protection that these areas offer and where they are located. Of the 18% of the territory covered by protected areas, only 6% are Integral Protection units (which exclusively allow the indirect use of natural resources). The other 12% are of Sustainable Use units (allowing the direct use of natural resources) where the Environmental Protection Area-EPA category predominates, the least restrictive of the entire system, which accounts for almost 30% of the total protected areas in Brazil [2]. Theoretically, the EPA’s mission is to reconcile the resident population and its economic interests with environmental conservation. Among its main functions are those of territorial planning, connectivity between other protected areas, reduction of impacts generated by human activities and containment of environmental damage, functioning as a buffer zone [4].

However, as they are mainly formed by a set of private properties, the EPA, in practice, contribute to real estate speculation and the increase in the price of enterprises and land located on their limits. They convey a false idea of restriction of use. The practice of suppressing vegetation cover in these areas has become a common strategy for valuing the remaining portions of vegetation around agricultural and real estate projects, serving as a green marketing tool for businesses [2]. In summary, EPA differ little from any other place where environmental legislation is respected, being therefore irrelevant to a system of protected areas [5]. In general, they are more economically important than biologically, and are highly vulnerable. Two central issues may justify the majority choice for this category of protected area: The first is related to the high dependence that the poorest population has on ecological resources, especially in rural areas, where a large part of them live off extraction and collection; The second and most important is due to the traditional view of economic development based on agribusiness and its expansion. In 2020, even with a 4.1% drop in Brazilian GDP compared to 2019, agribusiness activities rose by 2%, accounting for 26.6% of all the wealth produced in the country. This increase is related, among other factors, to the growth of crop and pasture areas [6]. The strong presence of agribusiness in the economy and politics generates a conflict of interests that prevent the creation of protected areas in strategic locations for the protection of Brazilian biodiversity, especially in relation to areas of Integral Protection. This directly reflects on the distribution of units between biomes and the type of category chosen.

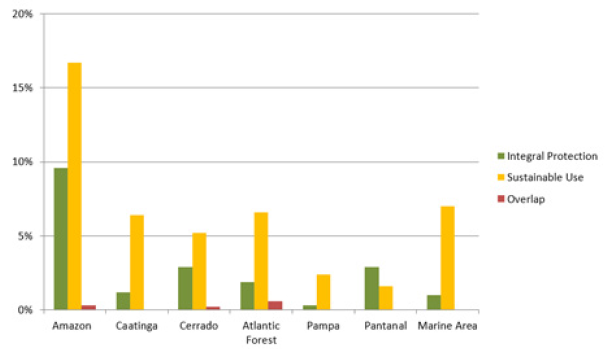

In the six biomes found in Brazil (Amazonia (amazon rainforest), Cerrado (savannah), Atlantic forest, Caatinga (tropical semi-arid vegetation), Pampas (grassland), and Pantanal (wetlands)), the only one with more than 17% of total area protected is the Amazon. This percentage corresponds to the target established by the Convention on Biological Diversity (Aichi Biodiversity Targets) for the period 2011-2020 [7,8]. In absolute terms, the country reached 17.2% of its continental area protected. However, the distribution in each biome is not homogeneous: Amazon, 28%, Caatinga, 8.8%, Cerrado, 8.3%, Atlantic Forest, 9.5%, Pampa, 3%, Pantanal, 4.6% [3]. Marine areas have 8% of their space protected, with a target of 10%. The composition between the areas of Integral Protection and those of Sustainable Use is also uneven, as shown in Figure 1. In addition to this imbalance in spatial distribution, critical managementrelated issues need to be resolved. Currently, the vast majority of units do not function effectively as part of the protected area system. These units were also not designed to guarantee ecological representativeness, based on the connection between them. This is directly related to the low capacity to use protected areas to generate employment, income and foreign exchange for the country [2,7]. When evaluating the management of federal protected areas and the fulfillment of their protection or conservation objectives, the brazilian government found that between 2005 and 2007 only 13% were highly efficient, while more than half were in the low effectiveness range. In the second cycle of analysis in 2010, 26% achieved high effectiveness, a number still far below the desired level and which compromises the effective protection of the country’s biodiversity and environmental resources [9]. Added to this is the fact that between 1981 and 2012, 93 changes were made to protected areas, causing a loss of legal protection of 52 thousand square kilometers [10], which corresponds to an larger area than Costa Rica.

Figure 1:Distribution of protected areas in Brazilian biomes.

Conclusion

Based on these considerations, it is concluded that the choice of EPA-type protected areas does not correspond to the real need of brazilian states and municipalities to protect their biomes. The reason is the low legal capacity of this category to restrict human activities that severely impact the environment. In the same way, the low protection given to other biomes, besides the Amazon, is a threat that needs to be fought. A greater diversity of species and greater productivity in the different ecosystems would mean keeping them more stable and sustainable, capable of withstanding environmental disturbances, such as prolonged periods of drought or even climate change [11].

References

- Araujo MAR (2007) Conservation Units in Brazil: From the Republic to World Class Management. SEGRAC, Brazil, p. 271.

- Machado RAS (2018) Protected natural areas as territorial planning instruments for urban sustainability: Application potential and the reality of management models in Salvador, Bahia-Brazil. International Doctoral School, Brazil, p. 229.

- WWF (2020) Conservation Units in Brazil. How much Brazil has in Conservation Units?

- Machado RAS, Lima EC, Oliveira AG (2020) Evolution of coverage and land use in the damping zone of the ecological station raso da Catarina between 1985 and 2015 and its relationship with the desertification process. Brazilian Applied Science Review 4(5): 3107-3122.

- Euclydes ACP, Magalhães SRA (2006) The Environmental Protection Area (APA) and the ecological ICMS in Minas Gerais: some reflections. Geographies Magazine 2(2): 39-55.

- IBGE (2022) National Accounts.

- IUCN, WWF, IPÊ (2011) Aichi Targets: Current Situation in Brazil, p. 73.

- SCDB (2014) Global Biodiversity Outlook. Montreal, Canada.

- ICMBio, WWF (2012) Management effectiveness of federal conservation units. Comparative evaluation of the applications of the Rappam method in federal conservation units, in the 2005-06 and 2010 cycles, p. 137.

- Bernard E, Penna LAO, Araújo E (2014) Downgrading, downsizing, degazettement, and reclassification of protected areas in Brazil. Conservation Biology 28: 939-950.

- Miller GT, Spoolman SE (2008) Essentials of Ecology, USA.

© 2023 Machado RAS. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)