- Submissions

Full Text

Advancements in Case Studies

Evaluating the Readiness of Health Facilities and Key Determinants for Hypertension Management in Bangladesh: Insights from the National Service Provision Assessment Survey

Aminur Rahman*

Department of Population Science and Human Resource Development, University of Rajshahi, Bangladesh

*Corresponding author:Aminur Rahman, Department of Population Science and Human Resource Development, University of Rajshahi, Bangladesh. Email: marahmanpops@ gmail.com

Submission:July 02, 2025;Published: July 22, 2025

ISSN 2639-0531Volume4 Issue4

Abstract

Background: Hypertension (HT) is the leading risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, yet its management

remains inadequate in low-and middle-income countries like Bangladesh. As the burden of HT continues

to grow, it calls for a robust and coordinated health system response. However, a comprehensive

assessment of health facility preparedness for hypertension management in Bangladesh has not been

conducted. This study aimed to evaluate the readiness of health facilities to manage hypertension and

identify key determinants influencing this readiness.

Methods: The analysis draws on data from the 2017 Bangladesh Health Facility Survey (BHFS), a

nationally representative, cross-sectional survey of health facilities. A total of 382 facilities at or above

the sub-district level were included. Readiness to provide HT services was assessed using a composite

index based on eight WHO SARA (Service Availability and Readiness Assessment) indicators, covering

three domains: trained staff and clinical guidelines, equipment and supplies, and availability of essential

medicines. A negative binomial regression model was applied to identify factors associated with service

readiness, adjusting for overdispersion in the count data.

Results: Only 0.19% of facilities were fully equipped to manage hypertension, with an average readiness

score of 3.72 out of 8. While basic diagnostic tools (e.g., BP apparatus, stethoscope) were available in

over 94% of facilities, major deficiencies were noted in staff training (16.6%), clinical guidelines (20.5%),

and availability of key antihypertensive medications such as ACE inhibitors (7.3%), thiazide diuretics

(12%), and calcium channel blockers (24.6%). Multivariable analysis revealed that NGO-run facilities had

higher readiness scores than their government or private counterparts. Facilities offering 24/7 provider

availability (IRR=1.07, p<0.05), those with client feedback systems (IRR=1.12, p<0.05), and those with

more trained staff (IRR=1.01, p<0.01) were significantly more prepared to manage HT.

Conclusion: Overall readiness to manage hypertension in Bangladesh’s health facilities is alarmingly low,

largely due to a shortage of trained personnel, lack of standardized clinical protocols, and limited access

to essential medications. Facility type, continuous provider availability, and systems for client feedback

are key determinants of readiness. These findings underscore the need for targeted interventions to

improve the health system’s capacity to deliver effective hypertension care.

Keywords:Hypertension; Health facility readiness; Bangladesh; Non-communicable diseases; Health systems strengthening

Introduction

Hypertension (HT), or elevated blood pressure, is a leading global public health issue and is widely recognized as the most prominent risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, stroke, kidney failure, and premature death [1]. An estimated 1.28 billion adults aged 30 to 79 years globally are affected by hypertension, with the majority residing in Low- and Middle- Income Countries (LMICs) [2]. The burden of HT is rising rapidly in LMICs, [3] including Bangladesh, [4] due to increasing urbanization, lifestyle changes, and an aging population. Poorly controlled hypertension could further exacerbate the already concerning Non- Communicable Disease (NCD) landscape in Bangladesh, placing additional strain on the health system and hindering socio-economic development [4]. Timely diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and consistent followup are critical in reducing the risk of HT-related complications and improving overall outcomes [5].

Despite the growing burden of hypertension in Bangladesh, effective management within the healthcare system remains limited. A considerable proportion of individuals with HT remain undiagnosed or inadequately treated, leading to poor control rates and increased risk of morbidity and mortality [4-6]. Existing research [7-9] has identified a major barrier in the form of limited readiness across health facilities-including shortages in essential medicines, diagnostic tools, trained personnel and clinical protocols-to provide adequate hypertension care. Thus, it is imperative to evaluate the current level of service readiness for HT management across diverse health facilities and to identify key factors influencing this readiness to inform future health system strengthening efforts.

A number of studies have explored the prevalence of hypertension and its associated risk factors within the Bangladeshi population [4,10-12]. Research has also highlighted significant gaps in awareness, treatment, and control of HT, particularly among rural and socioeconomically disadvantaged groups [4,13,14]. Additionally, studies have examined individual-level barriers to HT management, such as low health literacy, poor medication adherence and limited access to healthcare services [15,16]. However, there remains a relative lack of research assessing the readiness of health facilities in Bangladesh to effectively manage hypertension. Although previous studies have addressed certain aspects of chronic disease management-including diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and chronic respiratory conditions [17- 22] only a few have focused specifically on evaluating readiness to deliver HT services in Bangladesh [23,24]. Furthermore, these studies are either geographically limited [23] or focused on a specific facility type, [24] limiting their generalizability to the national level. Moreover, no comprehensive assessment has yet examined the multiple dimensions of HT service readinessincluding infrastructure, human resources, supply chains, and clinical protocols-across various levels of healthcare facilities.

Although existing literature has offered insight into the burden of hypertension [4-16] and some elements of healthcare delivery related to chronic diseases in Bangladesh [23,24] a clear gap remains regarding a nationally representative understanding of facility readiness for comprehensive HT care. A systematic assessment that includes critical dimensions such as resource availability, provider capacity, and adherence to clinical guidelines is urgently needed. Furthermore, identifying the facilitators and barriers to HT service readiness is essential to inform strategic interventions aimed at strengthening the health system. This study seeks to address these gaps by providing a nationally generalizable assessment of hypertension service readiness in Bangladesh and identifying the key determinants associated with it.

Methods

Study design

This study utilized a facility-based cross-sectional design.

Data source

The analysis draws on secondary data from the 2017 Bangladesh Health Facility Survey (BHFS 2017), a nationally representative survey aimed at evaluating the availability and readiness of healthcare facilities to deliver services related to tuberculosis, non-communicable diseases (including hypertension), family planning, and maternal and child health [25]. The survey collected detailed information on healthcare staffing, infrastructure, logistics (such as equipment and essential medicines), laboratory services and infection control, following standardized protocols. Key instruments included facility inventory questionnaires, interviews with healthcare providers, observational checklists, and exit interviews. This study specifically used data from the facility inventory questionnaire. Service readiness-referring to the availability of diagnostic tools, medications, supplies, and functional infrastructure-was assessed through interviews with facility managers or senior healthcare providers responsible for service delivery at each site.

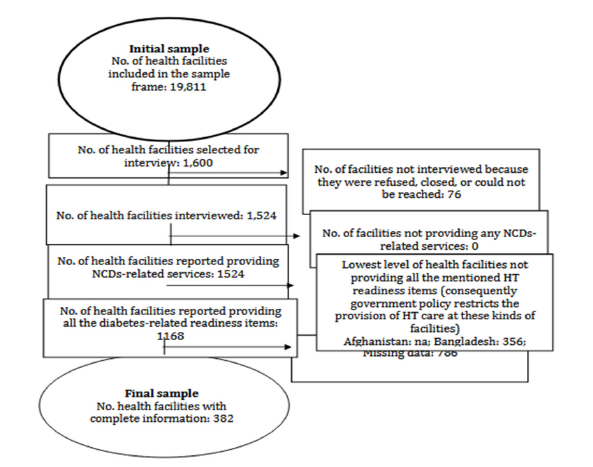

BHFS (2017) identified 19,811 registered healthcare facilities across Bangladesh’s seven administrative divisions: Barisal, Chittagong, Dhaka, Khulna, Rajshahi, Rangpur, and Sylhet [25]. The sampling frame included a range of facilities such as District Hospitals (DHs), Maternal and Child Welfare Centers, Upazila Health Complexes (UHCs), upgraded Union Health and Family Welfare Centers, Union subcenters/rural dispensaries, Community Clinics, private and public hospitals with 20+ beds, and NGO-run clinics. A stratified random sampling method was used, stratifying by managing authority and facility type, to select 1,600 facilities from 19,184 eligible facilities for the overall survey. For this study, which focuses on HT service readiness, the sample was refined. Since non-communicable disease services, including hypertension management, are typically provided at the sub-district level or higher in Bangladesh, [25] facilities below this level (such as Union subcenters and Community Clinics) were excluded. Additionally, facilities with incomplete data on key variables required for assessing HT readiness were also removed. After applying these exclusion criteria, a total of 382 healthcare facilities were included in the final analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1:selection of the sample for HT readiness.

Measures

Outcome variable

The primary outcome variable for this study was the readiness of a health facility to manage HT. This was operationalized as composite measures based on indicators essential for the provision of HT care in its varying forms. Eight specific items from the three main domains relevant to service provider readiness for HT were chosen and assessed: i) staff and guidelines components: presence of guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of HT and presence of at least one staff member who was trained on HT diagnosis and/or treatment in the last 24 months preceding the survey; ii) equipment and supplies components: functional digital blood pressure (BP) machine, or manual BP machine with stethoscope, adult weighing scale, and stethoscope; and iii) medicines and commodities components: availability of at least one angiotensin-converting enzyme (ace) inhibitor, availability of at least one thiazide diuretic, and availability of at least one calcium-channel blocker (amlodipine or nifedipine). Two primary criteria guided the selection of these eight indicators: (1) conformity with the WHO-SARA reference handbook, [26] which sets the framework for assessing health facility service availability and readiness; and (2) inclusion and measurement in the BFHS 2017 questionnaire [25]. For each of the eight indicators, a binary variable was created: the presence of the indicator was scored as 1 (present), while absence was scored as 0 (absent) as assessed and reported by the interviewers. Each facility’s score on HT readiness was subsequently determined by summing the number of indicators present, yielding a continuous score of 0-8, with higher scores representing a greater degree of readiness to deal with HT. A facility was said to be “fully ready” if all eight essential indicators were present.

Explanatory variables

A number of facility-level characteristics were examined in relation to HT service readiness to determine their potential as explanatory factors. The BFHS 2017 dataset 25 included these variables and prior research [17-24,27,28] on the factors influencing healthcare facilities readiness for chronic conditions including HT included these variables. The following explanatory variables included in the analysis are as follows: Facility location: Categorized as urban or rural. Managing authority: categorized into public (by government) and private (non-governmentowned). External sources of revenue: categorized based on support, whether they are receiving extra financial assistance from non-governmental organizations, the government, or neither. Quality assurance activities: a binary variable indicating whether the facility routinely performs quality assurance activities (e.g., mortality reviews, register audits) or not. External supervision: A binary variable indicating whether the facility received supportive oversight from a higher health authority (e.g., district or regional health management team) in the preceding year. Frequency of management meetings: a binary variable indicating whether the facility reported holding regular management meetings at least once every two to three months or less frequently/not at all. User fees: categorized as no fees, a single price per service, or a flat fee for all services.

Availability of trained health provider (24/7): a binary variable indicating whether a qualified health professional was on duty or available for emergencies around the clock at the facility. Feedback on patient opinions: binary variable indicating whether the facility had a system to collect and review feedback from patients. Facility diagnostic and/or treatment capabilities: they are classified into three groups: facilities that can diagnose and treat HT, facilities that can only diagnose HT, and facilities that can only treat HT. Facility Type: Primary Health Care Center (PHCC), private hospital, or government hospital. Number of trained HT care providers: a discrete quantitative variable representing the number of staff members trained in HT care at the facility.

Statistical analyses

First, descriptive statistical analyses were done to provide an overview of the characteristics of the study sample. Continuous variables were summarized with means while categorical variables were summarized using proportions. To model the relationship between selected explanatory variables with the facility HT readiness score (the count outcome variable), a negative binomial regression model was adopted. The negative binomial model was adopted because of overdispersion in the count variable HT readiness score, violating the assumption of Poisson regression [29]. This model adds a parameter to accommodate overdispersion. Incidence Rate Ratios (IRRs), corresponding 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs), and p-values were obtained from negative binomial regression analysis for each of the variables. IRR signifies the multiplicative effect of one-unit increase (for continuous variables) or presence of category (for categorical variables) in an explanatory variable on expected HT readiness score when other variables in the multiple regression model are held constant. All selected explanatory variables entered at once into the multiple negative binomial regression model to find the independent effects of different HT services’ readiness. A p-value of less than 0.05 determined the statistical significance for each association. Facility- level weighting was applied during analysis to account for the complicated sampling design of the BFHS 2017, involving stratification of different types of facilities across different locations and possible disproportionate sampling of facilities by type. Thus, the results would be representative of the national population of health facilities in Bangladesh. All statistical analyses were done using Stata V.16 software (StataCorp).

Ethical considerations

The study made use of secondary, anonymized data from the Bangladesh Health Facility Survey 2017, which is a publicly available data set. Since this data was devoid of identifying characteristics of any individual either from the facility staff or from the patients, ethical approval from a research ethics committee was not required for the analysis. The BFHS 2017 survey was approved by USAID, Macro International, and the institutional review boards of the respective ministries of health in Bangladesh. The data collection procedures conformed to the ethical principles formulated in the 2013 updates to the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants (facility managers or designated staff) ahead of their involvement in the survey.

Results

Descriptive statistics

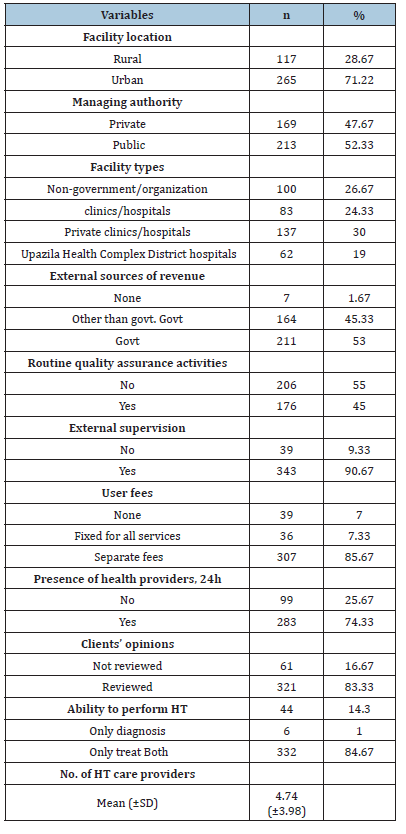

The Table 1 describes the background characteristics of the 382 surveyed health facilities of Bangladesh, drawing some important conclusions about their structure and functional readiness to deal with hypertension. Most facilities (71.22%) were in urban areas and 52.33% of the facilities were public authorized. Upazila Health Complexes constituted the largest health facility type, representing 30%, followed by NGO and private hospitals. Of the facilities, 53% received government funding; however, 45.33% also had some form of non-governmental financing. Alarmingly, 55% of the facilities underwent no routine quality assurance activities. Nonetheless, 90.67% received some form of external supervision and a large proportion (85.67%) of facilities also charged fees to their clients for services. About 74.33% of facilities had health providers available all day while 83.33% of facilities also examined client feedback. Regarding functional ability in examination and treatment, 84.67% of facilities were able to diagnose and treat HT, although diagnosis only (14.3%) or treatment only (1%) was offered by some. Facilities had an average of practically 4 trained HT care providers (mean= 3.84, SD=2.92), albeit with extreme variation.

Table 1:Percentage distribution of surveyed facilities according to background characteristics: Service Provision Assessment Survey in Bangladesh (n=382).

Note: Numbers are unweighted, and percentage are weighted

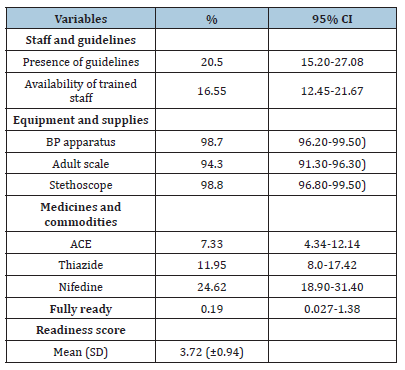

Table 2 shows that the availability of some key components for HT service readiness from surveyed health facilities in Bangladesh. Especially in the staff and guideline category, only 20.5% of the facilities-maintained guidelines for HT management, and 16.55% of the facilities had at least one staff member trained in HT care. Equipment and supplies are ready to go as almost every facility has a BP apparatus (98.7%), adult weighing scale (94.3%) and stethoscope (98.8%). However, there was a scandalous deficiency in availability: only 7.33% had ACE inhibitors, 11.95% had thiazide diuretics, and 24.62% had calcium channel blockers (nifedipine). Out of the surveyed facilities, only 0.19% were rated as fully ready for HT management, while the average readiness score was 3.72 out of 8.

Table 2:Percentage distribution of surveyed facilities according to availability of guidelines, equipment, and medicines to manage HT: Service Provision Assessment Survey, Bangladesh (n=382).

Note: CI= confidence interval

Multivariate analysis

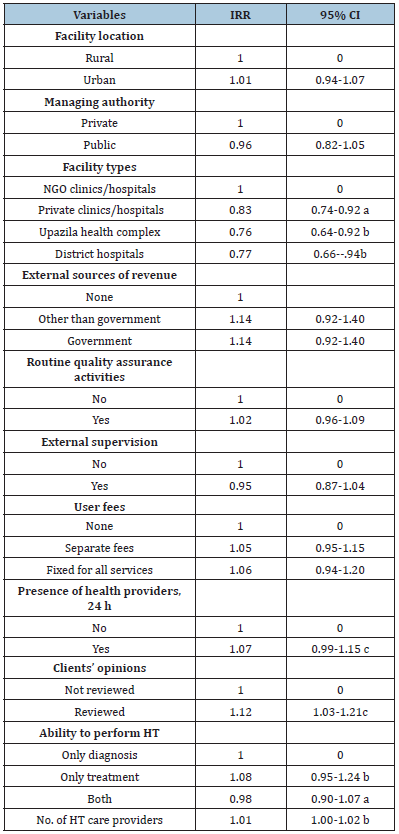

Table 3 shows results of a negative binomial regression analysis examining factors associated with health facility readiness to manage HT) in Bangladesh. Incidence Rate Ratios (IRRs) explain the influence of each variable on readiness scores referenced from the respective group. Type of health facility was an important determinant: readiness scores of private clinics/hospitals (IRR=0.83, p<0.001), Upazila Health Complexes (IRR=0.76, p<0.01), and district hospitals (IRR=0.77, p<0.01) were significantly lower when compared with NGO clinics/hospitals. Facilities that addressed clients’ opinions were conducive to becoming ready (IRR=1.12, p<0.05), and 24-hour availability of a health provider to a client was significant (IRR=1.07, p<0.05). Also, the number of trained HT care providers was statistically significant (IRR=1.01, p<0.01).

Table 3:Model of negative binomial regression for variables associated with health facility readiness to manage HT: Service Provision Assessment Survey in Bangladesh (n=382).

Note: CI=confidence interval; IRR=incidence risk ratio; Here a, b, and c indicate p<0.001, p<0.01 and p<0.05

Discussion

Main findings

This study provides a nationally representative measure of the readiness of health facilities in Bangladesh to address HT and shows major deficits in essential components of service delivery. Despite a generally high availability of some basic equipment (such as blood pressure apparatuses and stethoscopes), serious shortages exist in trained personnel, clinical guidelines and essential antihypertensive drugs. Only 0.19% of facilities were assessed as fully ready for HT management, with an average readiness score of 3.72 out of 8. Multivariable analyses showed that facility type, presence of 24/7 available healthcare providers, client feedback mechanisms, and number of trained providers are major determinants of HT service readiness.

Novelty and contributions

This study is one of the first to provide a comprehensive and nationally representative assessment of health facilities’ readiness for HT management in Bangladesh. While previous studies focused largely on the prevalence and control of HT at the population level or specific geographic settings, [4,17-22] this study attempts to bridge an important gap by assessing system-level readiness and identifying facility-level determinants that can feed into policy and planning processes. A readability index that meets the requirements of WHO-SARA 26 has added more strength and comparability to the results.

Comparison with other studies

With a mean of 3.72 out of 8, the alarmingly low HT readiness score found in our study resonates with findings from broader assessments of NCD service readiness in various LMICs. For example, a cross-sectional study from Tanzania on the preparedness of primary care facilities to respond to NCDs, such as hypertension, also noted a considerable lack of availability of essential medicines, diagnostic facilities, and adherence to treatment guidelines [30]. In the same way, a study showed reported suboptimal NCD readiness levels in primary healthcare facilities in select states of India, [31] which were infrastructure and human resource constraining factors, as well as the supply of essential drugs. Such similarities point toward the systemic challenges faced by healthcare systems in LMICs to deal adeptly with the mounting burden of chronic diseases like HT. The findings of profound deficiencies in the availability of HT management guidelines and trained personnel are in keeping with what is general on NCD care in resource-limited settings. A clear lack of standardized protocols and appropriately trained healthcare workers is consistently recognized as a major barrier to the provision of quality care for chronic diseases [9]. This becomes more serious because effective HT management largely depends on strict adherence to evidence-based guidelines and the sound judgment of healthcare professionals in terms of diagnosis, initiation of treatment, and ongoing monitoring.

Meanwhile, the relatively high availability of basic diagnostic equipment such as blood pressure apparatus, weighing scales, and stethoscopes in wide survey facilities of Bangladesh suggests foundational capacity for at least initial detection of HT. This contrasts with some settings where even basic diagnostic tools may be scarce [32]. However, the important deficit in essential antihypertensive agents ACE inhibitors, Thiazide diuretics, and calcium channel blockers as diagnosed in our study is, in fact, a serious barrier to proper management where diagnosis without access to the requisite treatment has limited clinical effect. Studies evaluating NCD readiness in LMICs have frequently noted this shortage of necessary medications, which is frequently ascribed to problems with the supply chain, insufficient finance, and difficulties setting priorities within healthcare systems [30,33-35].

The finding of the positive association between facilities that review client opinions and HT readiness supports a growing awareness of patient-centered care as a quality improvement driver. Obtaining insight from patients can yield information on gaps in service delivery as well as areas needing improvement, possibly promoting a healthcare environment that is more responsive and appropriately equipped (Sharma et al., 2021). In a similar vein, the significant impact of 24-hour health provider availability implies that ongoing access to care might improve readiness. The anticipated positive relationship between the number of trained HT health providers and readiness reiterates the primary importance of human resources capacity for healthcare services; a finding consistently noted by other studies on facility readiness across different disease domains. [21,22,33-36].

A more thorough comparison with previous research is necessary considering the fascinating discovery that private clinics/hospitals showed lower HT readiness compared to NGO clinics/hospitals. Notably, although some studies in other parts of the world have indicated maybe higher readiness due to adequate resource allocation in private facilities, [19,37] the current findings suggest quite the opposite in the context of Bangladesh. The health facility readiness study for diabetes and cardiovascular services in Bangladesh by different studies [21,22] presented a rather mixed, complex scenario, showing private hospitals/clinics higher on the overall readiness index but with difference across specific domains when compared with NGO facilities. The difference can be attributed to several things, including the focus of NGO clinics (which are often more public health oriented), their funding models, and regulatory oversight, as well as the populations served. There is further scope for in-depth qualitative and quantitative research to disentangle the reasons for these differences, in addition to identifying best practices from the relatively better-performing NGO sector that could be incorporated into how other facility types operate.

There are several areas of strength for this study. First, the use of a nationally representative dataset (BFHS 2017) enables research findings to be generalizable to the whole of Bangladesh. Second, the use of a standardized HT readiness index built upon WHO-SARA guidelines allows for a complete assessment with global comparisons. Its rigorous analysis through negative binomial regression, which considers the count nature of the readiness score while preemptively over dispersed, provides further strengthening of the estimates of the associations between facility characteristics and HT readiness. This is a critical public health issue for LMICs, and such studies add strong evidence for policy and programmatic interventions.

Despite the strengths of this study, there are limitations. Causal relationships between HT readiness and the determined determinants could not be established because of the crosssectional study design. The secondary data would keep information availability and quality tied to the original survey design and data collection processes. For example, the content and extent of training healthcare providers received was not explicit. More so, the readiness assessment focused on the availability of essential inputs at the facility level and did not directly assess the quality of care rendered or patient outcomes. Additionally, excluding facilities below the sub-district level might limit an understanding of HT readiness at the primary care level, particularly in more remote areas.

Conclusion

This research has brought to light the immense challenge of achieving necessary facility readiness for HT care across Bangladesh. The readiness of HT care was low especially regarding the existence of guidelines, trained human resources, and availability of essential medicines; therefore, it requires immediate attention and action. The findings indicate an essence of the type of the facility, with NGO clinics/hospitals being somewhat more ready amongst all facility types. Important interventions to be taken toward improving HT service readiness are training of healthcare providers, formulation and dissemination of clear guidelines for HT management, and guaranteed supply of essential medication. Building a culture of patient feedback and promoting adequate staffing levels are also considered important enabling factors. Future research must prove the reasons responsible for the differing readiness of facility types and explore in-depth the quality of HT care provision as an influence on patient outcome. Longitudinal studies to assess the impact of all interventions to strengthen the health systems readiness for managing HT and other noncommunicable diseases are recommended for Bangladesh.

References

- World Health Organization (2024) Hypertension.

- World Health Organization (2021) Hypertension.

- Schutte AE, Srinivasapura VN, Mohan S, Prabhakaran D (2021) Hypertension in low-and middle-income countries. Circ Res 128(7): 808-826.

- Kumar RT, Rahman M, Rahman MS, Halder N, Rashid MM (2024) Is gender a factor in socioeconomic disparities in undiagnosed, and untreated hypertension in Bangladesh? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 26(8): 964-976.

- Schmidt BM, Durao S, Toews I, Hohlfeld A, Nury E, et al. (2020) Screening strategies for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 5(5): CD013212.

- Mistry SK, Ali AM, Yadav UN, Khanam F, Lim D, et al. (2022) Changes in prevalence and determinants of self-reported hypertension among bangladeshi older adults during the covid-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(20): 13475.

- Gupta N, Coates MM, Bekele A, Dupuy R, Fénelon DL, et al. (2020) Availability of equipment and medications for non-communicable diseases and injuries at public first- referral level hospitals: A cross-sectional analysis of service provision assessments in eight low-income countries. BMJ Open 10(10): e038842.

- Adeke AS, Umeokonkwo CD, Balogun MS, Odili AN (2022) Essential medicines and technology for hypertension in primary healthcare facilities in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. PLoS ONE 17(2): e0263394.

- Jafar TH, Gandhi M, Jehan I, Naheed A, Finkelstein EA, et al. (2020) A community-based intervention for managing hypertension in rural South Asia. N Engl J Med 382(8): 717-726.

- Chowdhury MAB, Islam M, Rahman J, Uddin MT, Haque MR, et al. (2021) Changes in prevalence and risk factors of hypertension among adults in Bangladesh: An analysis of two waves of nationally representative surveys. PLoS ONE 16(12): e0259507.

- Rahman MA, Halder HR, Yadav UN (2021) Prevalence of and factors associated with hypertension according to JNC 7 and ACC/AHA 2017 guidelines in Bangladesh. Sci Rep 11: 15420.

- Hasan M, Khan MSA, Sutradhar I, Hossain MM, Yoshimura Y, et al. (2021) Prevalence and associated factors of hypertension in selected urban and rural areas of Dhaka, Bangladesh: Findings from SHASTO baseline survey. BMJ Open 11(1): e038975.

- Khan MN, Oldroyd JC, Hossain MB, Rana J, Renzetti S, et al. (2021) Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in Bangladesh: Findings from National demographic and health survey, 2017-2018. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 23(10): 1830-1842.

- Hossain A, Suhel SA, Islam S, Akther N, Dhor NR, et al. (2022) Hypertension and undiagnosed hypertension among Bangladeshi adults: Identifying prevalence and associated factors using a nationwide survey. Front Public Health 10: 1066449.

- Khanam MA, Lindeboom W, Koehlmoos TL, Alam DS, Niessen L, et al. (2014) Hypertension: Adherence to treatment in rural Bangladesh--findings from a population- based study. Glob Health Action 7: 25028.

- Hossain A, Ahsan GU, Hossain MZ, Hossain MA, Sutradhar P, et al. (2025) Medication adherence and blood pressure control in treated hypertensive patients: First follow-up findings from the PREDIcT-HTN study in Northern Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 25(1): 250.

- Biswas T, Haider MM, Das Gupta R, Jasim Uddin (2018) Assessing the readiness of health facilities for diabetes and cardiovascular services in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 8(10): e022817.

- Alam W, Nujhat S, Parajuli A (2020) Readiness of primary health-care facilities for the management of non-communicable diseases in rural Bangladesh: A mixed methods study. Lancet Glob Health 8: S17.

- Paromita P, Chowdhury HA, Mayaboti CA (2021) Assessing service availability and readiness to manage chronic respiratory diseases (CRDs) in Bangladesh. PLoS One 16(3): e0247700.

- Islam MR, Laskar SP, Macer D (2016) A study on service availability and readiness assessment of non-communicable diseases using the WHO tool for Gazipur district in Bangladesh. BJ Bio 7(2): 1-13.

- Huda MD, Rahman M, Rahman MM, Islam MJ, Haque SE, et al. (2021) Readiness of health facilities and determinants to manage diabetes mellitus: evidence from the nationwide Service Provision Assessment survey of Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Nepal. BMJ Open 11(12): e054031.

- Huda MD, Rahman M, Sarkar P, Islam MJ, Adam IF, et al. (2024) Health facilities readiness and determinants to manage cardiovascular disease in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Nepal: Evidence from the National Service Provision Assessment Survey. Glob Heart 19(1): 31.

- Jubayer S, Hasan MM, Luna M, Margaret F, Bhuiyan MR, et al. (2023) Availability of hypertension and diabetes mellitus care services at subdistrict level in Bangladesh. WHO Southeast Asia J Public Health 12(2): 99-103.

- ARK Foundation (2022) Preparedness of urban primary healthcare centers of Bangladesh in managing diabetes mellitus and hypertension. ARK Foundation, Bangladesh under the project titled "Community-Led Responsive and Effective Urban Health Systems (CHORUS)" funded by the UK Aid from the UK Government.

- National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Associates for Community and Population Research (ACPR), ICF International. Bangladesh health facility survey 2017.NIPORT, ACPR, and ICF International, 2019, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

- WHO (2013) Service availability and readiness assessment (SARA).

- Thapa R, Acharya K, Bhattarai N, Bam K (2024) Readiness of the health system to provide non-communicable disease services in Nepal: a comparison between the 2015 and 2021 comprehensive health facility surveys. BMC Health Serv Res 24(1): 1237.

- Bintabara D, Ngajilo D (2020) Readiness of health facilities for the outpatient management of non-communicable diseases in a low-resource setting: An example from a facility-based cross-sectional survey in Tanzania. BMJ Open 10(11): e040908.

- Andreas L, Samu M (2011) Using the negative binomial distribution to model overdispersion in ecological count data. Ecology 92(7): 1414-1421.

- Bintabara D, Mpondo BCT (2018) Preparedness of lower-level health facilities and the associated factors for the outpatient primary care of hypertension: Evidence from Tanzanian national survey. PLoS ONE 13(2): e0192942.

- Parameswaran Karthika, Agrawal Twinkle (2019) Readiness of primary health centers and community health centers for providing noncommunicable diseases-related services in Bengaluru, South India. International Journal of Noncommunicable Diseases 4(3): 73-79.

- Mutale W, Bosomprah S, Shankalala P, Mweemba O, Chilengi R, et al. (2018) Assessing capacity and readiness to manage NCDs in primary care setting: Gaps and opportunities based on adapted WHO PEN tool in Zambia. PLoS One 13(8): e0200994.

- Adinan J, Manongi R, Temu G. et al. (2019) Preparedness of health facilities in managing hypertension & diabetes mellitus in Kilimanjaro, Tanzania: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 19(1): 537.

- Hinneh T, Mensah B, Boakye H, Ogungbe O, Commodore MY (2024) Health services availability and readiness for management of hypertension and diabetes in primary care health facilities in Ghana: A cardiovascular risk management project. Glob Heart (1): 92.

- Lord KE, Acevedo PK, Underhill LJ, Cuentas G, Paredes S, et al. (2025) Healthcare facility readiness and availability for hypertension and type 2 diabetes care in Puno, Peru: A cross- sectional survey of healthcare facilities. BMC Health Serv Res 25(1): 297.

- Katende D, Mutungi G, Baisley K, Biraro S, Ikoona E, et al. (2015) Readiness of Ugandan health services for the management of outpatients with chronic diseases. Trop Med Int Health 20(10): 1385-1395.

- Rashid S, Mahmood H, Asma Iftikhar A, Komal N, Butt Z, (2023) Availability and readiness of primary healthcare facilities for the management of non- communicable diseases in different districts of Punjab, Pakistan. Front Public Health 11: 1037946.

© 2025 Aminur Rahman. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)