- Submissions

Full Text

Advances in Complementary &Alternative Medicine

Rehabilitation of an Elite Female Tennis Player Presenting with Medial Meniscus Injury and Musculoskeletal Dysfunction: A Case Study

Stephen P Bird1,2,3* and Peter Woodgate3

1James Cook University, Cairns, Australia

2Charles Sturt University, Bathurst, Australia

3Menteri Negara Pemuda dan Olahraga, Indonesia

*Corresponding author: Stephen P Bird, Associate Professor, Room A2.014a Sport and Exercise Science, College of Healthcare Sciences, James Cook University, Cairns QLD, Australia

Submission: May 18, 2018;Published: May 22, 2018

ISSN: 2637-7802Volume3 Issue1

Case Description

A 23 year old elite Indonesian female tennis player presented with two lower body pain sites. The major site of pain was localised over the medial meniscus of the right knee (Pain Site 1), of which she had suffered for 3 months. The second site of pain (Pain Site 2) was superficial over a large area of the antereolateral left thigh musculature and had been ongoing for an approximate period of 12 months. PS2 was localised and non-directional. Both pain sites were reported to be chronic and required the athlete to be withdrawn from competition during 2009.

Patient Assessment

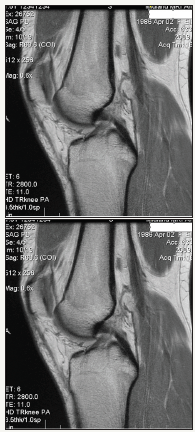

The athlete underwent physiotherapy assessment, in conjunction with IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation [1] and clinical diagnostic investigations (X-ray and MRI-Figure 1) of the right knee (PS1) in New Zealand following international competition. Physiotherapy reports were presented during initial consultation with an Exercise Physiologist. During the assessment self-reported pain (Numeric Rating Scale) [2] was triggered by moderate pressure over the area on palpation. PS1 was reported as a 7/10. Orthopaedic assessments were performed including a Lachman’s test, Anterior and Posterior draw tests and Varus and Valgus force tests [3], only the Varus force test elicited pain at the site of the right medial meniscus. Additional pain onset triggers were assessed via functional field assessments that require knee movements essential for sport including self-weight bearing with affected knee flexion >30°, lateral push off and sudden eccentric loading and change of direction movements [4-7]. Self-reported pain at PS1 was reported as 7/10. The second site of the athlete’s pain (PS2) was at the antereolateral aspect of the left thigh. Pain onset was triggered by rapid concentric and eccentric muscle actions and dynamic lateral movement drills (lateral shuffle). Self-reported pain at PS2 was reported as 8/10. Collectively, these findings were suggestive of 1) PS1: Small focal tear with associated chondral damage to the right leg medial meniscus and a grade 1 sprain of the ACL fibres, as revealed by MRI imaging; and 2) PS2: Chronic nonspecific ungraded tear to the superficial antereolateral left thigh musculature (Figure 1).

Figure 1 : Magnetic resonance images viewing the right knee presented by athlete.

Exercise Rehabilitation

Program design

Exercise rehabilitation was conducted over a 3.5 month period (May-August, 2009). Initial meetings involving medical staff, the strength and conditioning coach, exercise physiologist and athlete addressed results from clinical diagnostic test and functional field assessments [4-7]. Further discussion explored specific rehabilitation considerations including 1) Severity of injury-structure involved and associated damage; 2) Nature of injury-macrotraumatic/microtraumatic; 3) Stage of injury-healing process; and 4) Irritability of injured site-load tolerance. Collectively, it was agreed that integration of key rehabilitation and strength and conditioning principles [8-12] would allow the rehabilitation program to progress following the reactivation continuum [13]. This would ensure structured progression through rehabilitation exercises, aquatic rehabilitation, strength and integrative neuromuscular training, functional loading patterns and finally sport-specific movement-based drills. Importantly, the program design employed a goal oriented approach with the primary goal to maximise transfer of training effect through a phase-specific approach to rehabilitation. Including the athlete in this process was critical to ensure athlete “buy in”. This allowed the athlete to contribute to the program, providing them with sense of ownership and understanding of the phase-specific approach, which centred on the following 1) Develop optimal levels of lumbopelvic stability and strength endurance; 2) Focus on neural adaptations instead of absolute strength gains; and 3) Increase proprioceptive demands in preparation for to sport-specific activity transition.

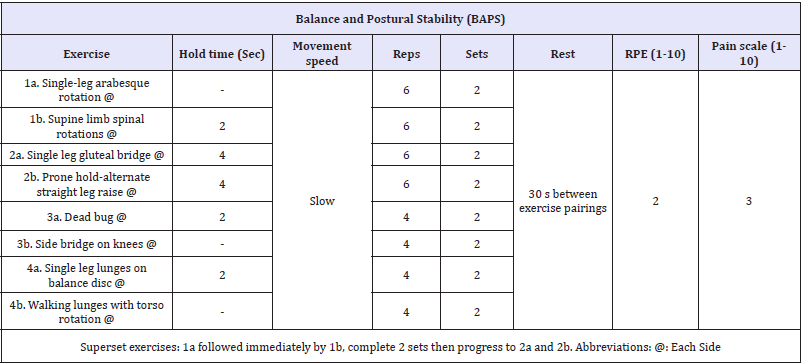

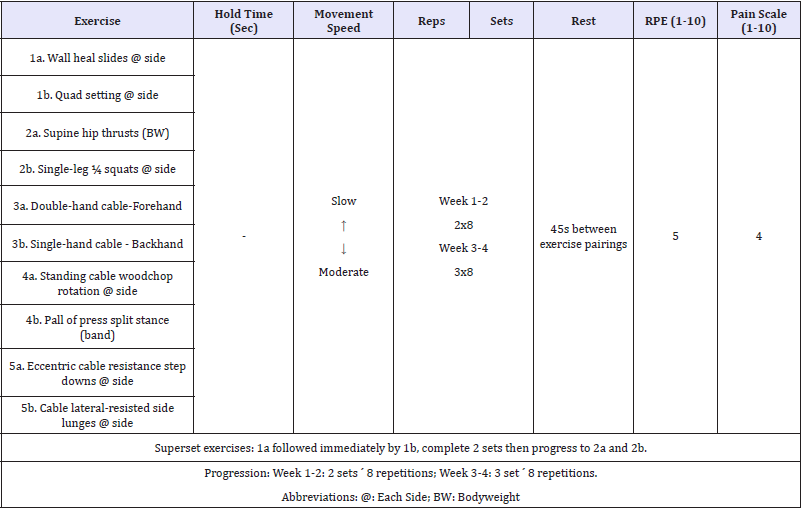

It was determined that five main focus areas were deemed essential in achieving successful functional progression of the rehabilitation program [9-11,14], these being 1) Rehabilitation exercises matched the current physiological state of the athlete [15]; 2) Exercise selection and progressions were based upon the acute physiological responses of the athlete, as determined by adverse responses in inflammation and pain [16]; 3) Aquatic rehabilitation (unloaded) would provide an effective environment to reduced load-bearing capacity of the injured structure yet allow movement patterns that promote dynamic flexibility, mobility and stamina [17,18]; 4) Integrative neuromuscular training (balance and postural stability - BAPS) activities [19,20] with sport-specific tennis movements are used as movement preparation strategy; and 5) Specific spine stabilization exercises were included to increase lumbo-pelvic-hip stability as the trunk is the functional unit of the kinetic link system [21-23]. This is of major importance as during a tennis stroke it is estimated that 51% of the total kinetic energy and 54% of the total force are developed in the leg-hip-trunk linkage [24].

Program implementation

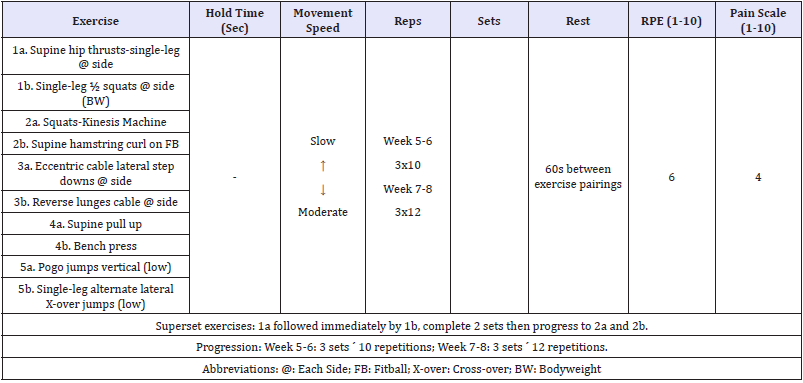

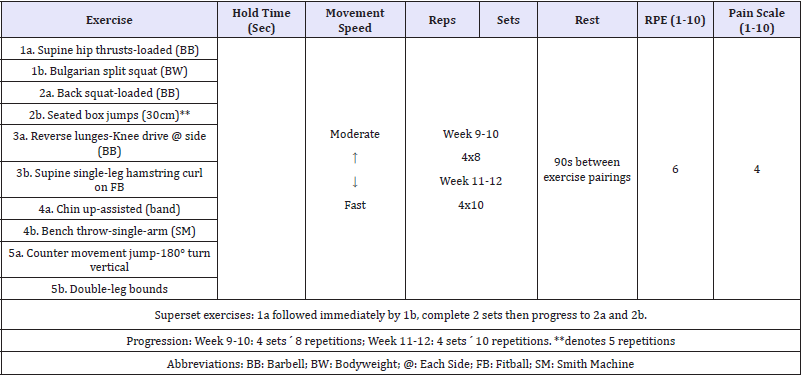

The athlete was required to attend at the National Tennis Training Centre (NTTC) for weekly consultations with their technical coach and strength and conditioning coach. Rehabilitation sessions were performed off-site twice per week during the first 4-week block (Tables 1, 2 & 3), following which specific prehab/ rehab exercises were integrated into the strength and conditioning program conducted at the NTTC (Tables 4 & 5). The ‘POLICE’ acronym [25] was used to guide acute management and minimise exercise induced inflammation to assist acute muscular recovery. This was adhered to in rehabilitation and also advised following all strength and conditioning sessions. Progression criteria to advance to Phase 2 was guided by pain and inflammation, and included 1) Pain scale <4 in range of motion >75% of uninjured side; 2) Pain scale <4 on isometric contraction in mid, inner and outer range; and 3) Minimal inflammation.

Table 1: Movement preparation: Integrative neuromuscular training.

Table 2: Aquatic rehabilitation.

Table 3: Phase 1: Restore range of motion, muscular strength and endurance (Weeks 1-4).

Table 4: Phase 2: Proprioception and level 1 plyometric exercise (Weeks 5-8).

Table 5: Phase 3: Sport-specific functional re-integration (Weeks 9-12).

Quantification of session/daily training load during and the potential implications on separating physiological and biomechanical load-adaptations [26] may have specific relevant during rehabilitation and return from injury [27]. As such, the session-RPE (sRPE) method was employed, which has been widely used in training load quantification for various types of training across multiple sports, including tennis [28], as determined by multiplying a sessional rating of perceived exertion (RPE: Borg category-ratio 10 [CR-10]) by the session duration (minutes) [29]. sRPE training load values were used to quantify changes in weekly workload, with a terminal change in weekly workload capped at no more than 10%. Importantly, such loading did not elicit pain responses above 6 on the pain scale, which was pre-determined as the upper limit for terminating the training session.

To assist with overall athlete recovery and wellness, a modified version of the 100-point recovery checklist, as described by Bird [30] was employed. The athlete was encouraged to utilize daily recovery strategies with the target goal of achieving a minimum of 80 recovery points per week. The numerical value of each recovery strategy has been determined by the evidence-based effectiveness of the strategy and the level of athlete proactive engagement required (please see Bird [30] for complete description of the 100-point recovery checklist; and Vaile et al. [31] for an extensive review on the science vs. practice or recovery).

Outcomes

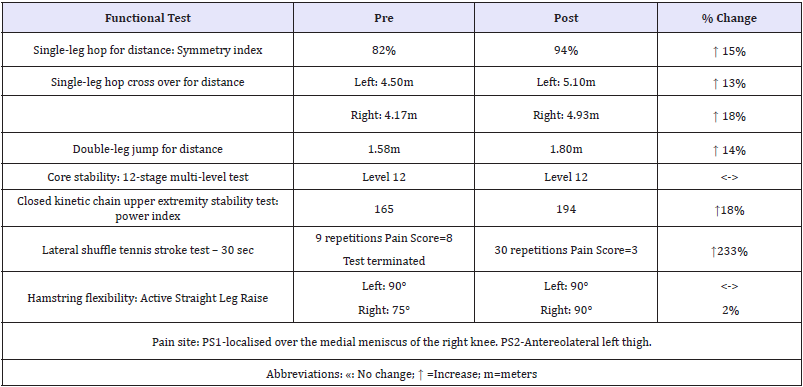

Functional testing data is presented in Table 6. On completion, all functional hop tests displayed improvement. The single-leg hop for distance symmetry index improved by 12%, while single-leg hop cross over for distance ability significantly improved in both symmetry index and distance. When displayed as a percentage of height, double leg jump distance improved from 98% to 112%. Shoulder stability, as accessed via the Closed Kinetic Chain Upper Extremity Stability Test (CKCUEST) [32] was maintained, however the shoulder power index improved by 18% from 165 to 194, well above normative values [33]. Core stability was maintained throughout the training period, however test exertion difficulty (as determined via RPE) improved from an RPE rating of 7 (pre) to an RPE rating of 3 (post). The Lateral shuffle tennis stroke test improved dramatically, from test termination due to pain score of 8/10, to post, 30 repetitions (pain score 3/10). Hamstring flexibility, as measured by active straight leg raise (ASLR) assessment improved by 15°.

Table 6: Functional testing data.

Conclusion

This case study presented a 12-week phase-specific rehabilitation program for an elite female tennis player following nonsurgical treatments. At the last clinical visit, 5 months after initial presentation, the patient significantly improved on the IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation (5th percentile of gender and age normative data) [1], had normal ROM and strength, and passed all functional testing. The outcomes demonstrate improvements in musculoskeletal function relating to the deficits presented on initial consultation. Through the integration of rehabilitation exercise following the reactivation continuum [13], exercise prescription based on improving muscular weakness, asymmetry, athletic posture, and sport-specific strength transfer, the athlete returned to international competition (25th South East Asian Games, Vientiane, Laos, December, 2009) with no injury reoccurrence.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the athlete and coaches from Persatuan Tenis Seluruh Indonesia (Tennis Indonesia), and Program Atlet Andalan, Menteri Negara Pemuda dan Olahraga, Jakarta Indonesia for their dedication and collaboration.

References

- Anderson AF, Irrgang JJ, Kocher MS, Mann BJ, Harrast JJ (2006) The international knee documentation committee subjective knee evaluation form. Am J Sports Med 34(1): 128-135.

- Bahreini M, Jalili M, Moradi LM (2015) A comparison of three self-report pain scales in adults with acute pain. J Emerg Med 48(1): 10-18.

- Rossi R, Dettoni F, Bruzzone M, Cottino U, D’Elicio DG, et al. (2011) Clinical examination of the knee: know your tools for diagnosis of knee injuries. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol 3: 25.

- Naimark MB, Kegel G, O’Donnell T, Lavigne S, Heveran C, et al. (2014) Knee function assessment in patients with meniscus injury:A preliminary study of reproducibility, response to treatment, and correlation with patient-reported questionnaire outcomes. Orthop J Sports Med 2(9).

- Cates W, Cavanaugh J (2009) Advances in rehabilitation and performance testing. Clin Sports Med 28(1): 63-76.

- Bird SP, Markwick WJ (2016) Musculoskeletal screening and functional testing: Considerations for basketball athletes. Int J Sports Phys Ther 11(5): 784-802.

- Bird SP, Woodgate P (2009) Development and implementation of musculoskeletal testing protocols for the Indonesian elite athlete high performance program. Report for Program Atlet Andalan, Indonesian High Performance Sport Program, Charles Sturt University, Australia, pp. 1-22.

- American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, American College of Sports Medicine, American Medical Society for Sports Medicine, American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine, the American Osteopathic Academy of Sports Medicine (2015) The team physician and strength and conditioning of athletes for sports: A consensus statement. Med Sci Sports Exerc 47(2): 440-445.

- Reiman MP, Lorenz DS (2011) Integration of strength and conditioning principles into a rehabilitation program. Int J Sports Phys Ther 6(3): 241-253.

- Lorenz DS, Reiman MP (2011) Performance enhancement in the terminal phases of rehabilitation. Sports Health 3(5): 470-480.

- Dhillon H, Dhilllon S, Dhillon MS (2017) Current concepts in sports injury rehabilitation. Indian J Orthop 51(5): 529-536.

- Werner G (2010) Strength and conditioning techniques in the rehabilitation of sports injury. Clin Sports Med 29(1): 177-191.

- Liebenson C (2006) Functional training for performance enhancement- Part 1: The basics. J Bodywork Movement Ther 10: 154-158.

- Beam JW (2002) Rehabilitation including sport-specific functional progression for the competitive athlete. J Bodywork Movement Ther 6(4): 205-219.

- Bomgardner R (2001) Rehabilitation phases and program design for the injured athlete. Strength Cond J 23(6): 24-25.

- Wallden M (2009) The best rehabilitation programs in the world. J Bodywork Movement Ther 13: 192-201.

- Wicker A (2011) Sport-specific aquatic rehabilitation. Curr Sports Med Rep 10: 62-63.

- Prins J, Cutner D (1999) Aquatic therapy in the rehabilitation of athletic injuries. Clin Sports Med 18(2): 447-461.

- Bird SP, Stuart W (2012) Integrating balance and postural stability exercises into the functional warm up for youth athletes. Strength Cond J 34(3): 73-79.

- Myer GD, Ford KR, Palumbo JP, Hewett TE (2005) Neuromuscular training improves performance and lower-extremity biomechanics in female athletes. J Strength Cond Res 19(1): 51-60.

- Chiu LZF (2007) Are specific spine stabilization exercises necessary for athletes? Strength Cond J 29: 15-17.

- Gamble P (2007) An integrated approach to training core stability. Strength Cond J 29: 58-68.

- Liebenson C (2004) Spinal stabilization-an update. Part 3-training. J Bodywork Movement Ther 8: 278-285.

- Kibler WB (1995) Biomechanical analysis of the shoulder during tennis activities. Clin Sports Med 14(1): 79-85.

- Bleakley CM, Glasgow P, MacAuley DC (2011) PRICE needs updating, should we call the POLICE? Br J Sports Med 46(4): 220-221.

- Vanrenterghem J, Nedergaard NJ, Robinson MA, Drust B (2017) Training load monitoring in team sports: A novel framework separating physiological and biomechanical load-adaptation pathways. Sports Med 47(11): 2135-2142.

- Blanch P, Gabbett TJ (2016) Has the athlete trained enough to return to play safely? The acute:chronic workload ratio permits clinicians to quantify a player’s risk of subsequent injury. Br J Sports Med 50(8): 471- 475.

- Coutts AJ, Gomes RV, Viveiros L, Aoki MS (2010) Monitoring training loads in elite tennis. Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria & Desempenho Humano 12(3): 217-220.

- Haddad M, Stylianides G, Djaoui L, Dellal A, Chamari K (2017) Session- RPE method for training load monitoring: Validity, ecological usefulness, and influencing factors. Front Neurosci 11: 612.

- Bird SP (2011) Implementation of recovery strategies: 100-point weekly recovery checklist. Int J Athl Ther Train 16: 16-19.

- Vaile J, Halson SL, Graham S (2010) Recovery review-Science vs practice. J Aust Strength Cond 18(Supp 2): 5-21.

- Roush JR, Kitamura J, Chad Waitsc M (2007) Reference values for the Closed Kinetic Chain Upper Extremity Stability Test (CKCUEST) for collegiate baseball players. N Am J Sports Phys Ther 2(3): 159-163.

- Ellenbecker T, Manske R, Davies G (2000) Closed kinetic chain testing techniques of the upper extremities. Orthop Phys Ther Clin North Am 9: 219-229.

© 2018 Stephen P Bird. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)