- Submissions

Full Text

Archaeology & Anthropology:Open Access

Double-Headed Eagle Symbol of The Russian Empire and Local Replica in The Kingdom of Georgia

Eka Avaliani* And Tamta Tskhovrebadze

International Black Sea University, School of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, Georgia

*Corresponding author:Eka Avaliani, International Black Sea University, School of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, Georgia

Submission: February 15, 2023Published: March 28, 2023

ISSN: 2577-1949 Volume4 Issue4

Abstract

Nowadays, the role of symbols has been imperative for scholars to shape national identity both for nationalism and memory studies. The article focuses on the formation of the historical consciousness of the Russian imperial court and Eastern Georgian state by creating a shared past, addressing the Byzantine imperial symbols. The appropriation of the Byzantine symbol of power, the eagle (single-headed/doubleheaded) by both states, directly emphasized their political views, ambition, and nexus with the Byzantine Empire and expressed an awareness of their unity with the Christian Empire. The appropriation of the legacies of the Byzantine Empire between two historical actors, claiming an inheritance visibly demonstrates how and why they praised, esteemed, and evaluated the medieval Byzantine Empire as the Model state and how they were able to claim the inheritance to which they were entitled.

Keywords:Eagle; Imperial symbols; Memory; National identity; Symbols of power

National Identity and Symbols of Power

After the fall of the Eastern Roman Empire, a series of national histories written in Europe sought to discover, rediscover, or even invent the connection of their states with the Byzantine Empire. After the decline of Eastern Rome, the Byzantine Empire, and the tragic fall of Constantinople on May 29, 1453, the myth of the immortality of the Christian imperial civilization tremble. Constantine XI Palaeologus, the last emperor of Eastern Rome (February 8, 1405 - May 29, 1453), died in the battle. The fall of the Byzantine Empire was the collapse of Christianity in the East and the victory of the Islamic world, but it also was a kind of challenge for those Orthodox Christian countries who had hegemonic ambitions over the transregional space. The “Third Rome” became an imaginary space and a symbolic concept. This concept implies the eternality of Rome. Different states claimed to “relocate” Rome in its space1. Germans, Austrians and Italians and other peoples and states considered the Third Rome in their own space [1-3]. This ambition to be seen as Third Rome arose in Russia after the fall of Constantinople in the XV-XVI centuries. After Baptism, Russia felt a closeness to Byzantium. Therefore, after the fall of the Second Rome, Russia grounded the idea of the Third Rome on its ideological aspirations and prospects of taking peaceful diplomatic contacts with the West. During this period, the concept was introduced publicly by prominent writings and directed the political cursor of the country aligned with ideological transformations and ambitions. The double-headed eagle, as a symbol of Byzantine state power, appeared in Byzantine art in 13012. The symbol of the eagle expressed the idea of invincibility and eternity of the Roman Empire [4-7]. The Byzantine Empire appropriated and expressed the spread-winged eagle in its iconographic message. Later, a national symbol of the House of Palaeologus became a double-headed eagle3. Images of one-headed and two-headed eagles are associated with Roman and Eastern Roman state symbols.

Russian and Georgian Cases as Examples

After the fall of Constantinople, the Russian king Ivan III married the Byzantine princess Sophia in 1472, the representative of the Imperial Palaiologan family, who was a close relative of the last king4 Ivan adopted the golden Byzantine double-headed eagle in his seal, first documented in 1472. The decline of the Byzantine Empire strengthened the opinion about the rightful inheritance of Moscow. The declaration of Moscow as the “Third Rome” was based on a new religious concept and a mixture of political ideas. According to state doctrine, the Russian king should act as a supreme ruler (sovereign and legislator) of Christian Eastern Orthodox nations and become a defender of the Christian Eastern Orthodox Church. Herewith the Church should facilitate the Sovereign in the execution of his functions supposedly determined by God, the autocratic administration5. That logic was derived from assumption that supremacy was not an achievement of the country itself, rather than it was seen as an instrument God chosen to fulfil6. The coat of arms of the Russian Empire escutcheon was golden with a black two-headed eagle crowned with two Imperial Crowns, over which the same third crown, enlarged, with two flying ends of the ribbon of the Order of Saint Andrew [8-11]. After fragmentation of the unified Kingdom of Georgia in the late 15th century, the branches of the Bagrationi dynasty ruled the three breakaway Georgian kingdoms, the Kingdom of Kartli, the Kingdom of Kakheti, and the Kingdom of Imereti, until Russian annexation in the early- 19th century. While the 3rd article of the 1783 Treaty of Georgievsk guaranteed continued sovereignty for the Bagrationi dynasty and their continued presence on the Georgian throne, the Russian Empire later broke the terms of the treaty and fully annexed the protectorate.

An eagle as a symbol of power appeared during the reign of Erekle II, the Georgian monarch of the Bagrationi dynasty (the King of Kartli and Kakheti from 1762 until 1798). King Erekle II placed his kingdom under the formal Russian protection. As a result of the Treaty of Georgievsk in 1783, the Georgian King finally obtained the guarantees he had sought from Russia, transforming Georgia into a Russian protectorate. Erekle II formally repudiated all legal ties to Persia and placed his foreign policy under the Russian imperial control. Political relationships with Russian Empire replicated on the Georgian royal iconography, in 1781,1787,1789 years with a double-headed eagle appearing on royal copper coins7. During the 1780s, Erekle II’s name was placed in full in Asomtavruli: ႨႰႠႩႪႨ (IRAKLI) and the image used was a double-headed eagle8. On the one hand, the double-headed eagle, indicated the bonds with the Byzantine, and, on the other hand, demonstrated ties with the Russian Empire. The appropriation of the symbol of Byzantine Empire between two political actors (Russian Empire and Georgian State) claiming their inheritance, visibly demonstrates how and why they esteemed and valued legacies of the Christian Empire and how they were able to claim the inheritance to which they were entitled to9.

However, during the Russo-Turkish War (1787-1792), a Tbilisi-based small Russian force evacuated from Georgia, leaving Erekle II alone to face new threats from Persia. In 1795, Agha Mohammad Khan demanded that Erekle II to acknowledge Persian suzerainty. However, the Georgian King refused, and in September 1795, the Persian army of 35,000 moved into Georgia. After a valiant defense of Tbilisi at the Battle of Krtsanisi, Erekle’s small army was completely defeated. Tbilisi was sacked. Despite being betrayed by the Russian empress, the Georgian King still relied on a belated Russian support. In 1796, Empress Catherine II directed the Russian expeditionary forces into the Persian territories, but her successor Paul I again withdrew all Russian troops from the region. Mohammad Khan launched his second campaign to punish Georgians for their alliance with Russia. Since the year 1796, the images of a double-headed eagle disappeared from the Georgian coins. The images of a double-headed eagle were replaced with a single-headed Roman-Byzantine imperial eagle. Subsequently 1796 we have copper coins of Erekle II with the effigy of an eagle produced at Tbilisi mint. The King also produced gold coins with the effigy of an eagle, two samples of which are maintained in Hermitage, Saint-Petersbur10. According to Yevgeniy Pakhomov’s11 the change in the imagery, specifically the reduction of the number of the eagle-heads, was inspired by the alteration of the weight standard and the desire to make new coins easily distinguishable from the previous batch.

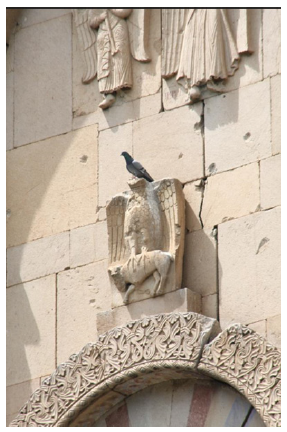

However, the authors of this paper presume that change and alteration of the symbols exclusively coincide with the political views of the Georgian King and reflect his sharp disagreements regarding Russian imperial policy. The single-headed image of an eagle contains Roman-Byzantine elements, which shows a spiritual and direct succession of Georgia to the Byzantine Empire. Christian statehood by the “Byzantinizing” Georgian Bagratids in southwest districts of Tao/Tayk‛, Klarjet‛i/Kłarjk‛, and Shavshet‛i/ Shawshēt‛ adopted Byzantine traditions, doctrines, and symbols of power. Bagrationi of Tao-Klarjeti founded Oshki and Khakhuli Monasteries in the historical Tao province. Oshki was built between 963 and 973. The monastery is located in Turkey, in the village of Çamlıyamaç, in northeastern Erzurum Province, bordering Artvin Province. Khakhuli Monastery was founded in the second half of the 10th century by King David III Kurapalates. Oshki’s eagle is depicted with a mammal (though sometimes perceived as a calf, a lamb or a sheep) in its talons (Figure 1). Khakhuli’s eagle is depicted with half-open wings, holding a deer in its claws (Figures 2 & 3)12. The architecture of the Svetitskhoveli Cathedral, which dates back to 1020, is based on the cross-dome style, which emerged in Georgia in the early Middle Ages. The church facades are richly decorated. A writing above the windows of eastern facade indicates that the church was built by Katolikos Melchisedek. Above it, on two low reliefs are represented an eagle with open wings and a lion under it (Figure 4). King Erekle’s decision to revive the Byzantine one-headed eagle indicates king’s political claim, that Georgia was a direct successor to Byzantium in the Middle East (Figure 5). On August 10, 2000, Georgian bi-metallic 10 Lari coins were put into circulation to commemorate the 3,000th anniversary of Georgian statehood. On the obverse features of the coin depicted the bas-reliefs of the eagle and lion from the 11th century Svetitskhoveli cathedral. The coin is circled with a legend that reads, in Georgian, “3,000th anniversary of Georgian statehood”. Therefore, the nature and the diplomatic course of the state is represented by the extensive importance and use of the state symbols. Symbolism sheds light to the State’s intentions and orientation that are predominantly objectified. The cases discussed above further reveal the importance of symbolism in diplomacy and states experiences to attain their political intentions and alignment. The present evidence makes it plausible that this Byzantine symbol of the eagle is invested with the forms of power and the link between the appropriation of Imperial heritage and nation-building are blended even in contemporary history.

Figure 1:The single-headed image of an eagle from Oshki Monastery in the historical tao province.

Figure 2: The single-headed image of an eagle from Khakhuli Monastery, in the historical Tao province (Former part of Georgian Medieval Kingdom, Modern Turkey).

Figure 3:The single-headed image of an eagle from Khakhuli Monastery, in the historical tao province.

Figure 4:Eagle with open wings and a lion under it. Svetitskhoveli Cathedral, Georgia

Figure 5:Golden coin with the single-headed image of an eagle, Erekle II, Georgia

References

- Avaliani E (2021) Four eternal cities: Jerusalem, athens, rome and carthage: Their origin, power, and transforming influence on western history. Edwin Mellen Press, USA.

- Soloviev AV (1982) The heraldic emblems of byzantium and the slavs. Seminarium Kondakovianum (in French) 7: 119- In: Cernovodeanu D (1982) Contributions to the study of byzantine and post-byzantine heraldry. Yearbook of Austrian Byzantine Art 32 (2): 409-422.

- Avaliani E (2020) Roman-byzantine eagles in the georgian context from the early antiquity to the medieval and modern periods. Annals of Global History 2(2): 24-29.

- Barker JW (1972) Renaissance influences and religious reforms in Russia: Western and post-byzantine impacts on culture and education (16th-17th centuries). History of Education Quarterly 12(2): 232-

- Mashkov AD (2019) Moscow is the Third Rome. Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopedia, Ukraine.

- Laats A (2009) The concept of the third rome and its political implications.

- Paghava (2017) Profitability of minting civic copper coins and the identification of emerging nationalism as seen through coin imagery, a case study of the East-Georgian kingdom kartl-kakheti. In: Faghfoury, Mostafa (Eds.), Iranian Numismatic Studies. A Volume in Honor of Stephen Album. Hardbound. Lancaster, England.

- Avaliani E (2020) Roman-byzantine eagles in the georgian context from the early antiquity to the medieval and modern periods. Annals of Global History 2(2): 24-29.

- Pakhomov E (1970) Coins of Georgia. Tbilisi, Georgia.

- Beridze V (1981) Architecture tao-clarjeti. Tbilisi, Metsniereb, Georgia, 118: 59-61.

- Djobadze W (1986) Observations on the architectural sculpture of Tao-Klarjet'i churches around one thousand AD. In: Feld O, Peschlow U, Habelt BR (Eds.), Studies on late antiques and byzantine art: Dedicated to friedrich wilhelm deichmann. Part 2, 81-100

© 2023 Eka Avaliani. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)