- Submissions

Full Text

Trends in Telemedicine & E-health

Providers’ Perspectives on Electronic Data- Sharing with Patients: A Qualitative Descriptive Study

Selena Davis*1 , Kathy L Rush2, Lindsay Burton3 and Mindy A Smith4

1Department of Family Practice, Canada

2School of Nursing, Canada

3School of Nursing, Canada

4Department of Family Medicine, USA

*Corresponding author:Selena Davis, Department of Family Practice, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Submission: November 11, 2022; Published: November 23, 2022

ISSN: 2689-2707 Volume 3 Issue 5

Abstract

Little is known about data sharing between healthcare providers and their patients. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and the dramatic shift to virtual care delivery, there is a growing imperative to understand the types of patient-generated data used in patient care; the digital tools, functionalities, and processes used in sharing these data; and the barriers and facilitators to data sharing. This descriptive qualitative study explored the electronic data-sharing practices of primary healthcare providers with their patients. Providers’ (n=14) electronic data-sharing practices during the pandemic and their use of asynchronous and synchronous digital data-sharing modalities were highly variable. Most providers used telephone as their main synchronous modality for data sharing, with asynchronous modalities used to a limited extent or to complement synchronous data sharing. Providers who rarely used asynchronous modalities only collected patient-generated data in select circumstances. Barriers and facilitators of datasharing practices included digital infrastructure, integration, cost, patient factors, and provider factors such as care team composition, capacity, and percentage of virtual to in-person visits. Identifying solutions to support and enable providers and their patients with integrated digital tools and technologies and best practices for data sharing is necessary to optimize quality care and address care gaps.

Abbreviations: BP: Blood Pressure; FG: Focus Groups; COREQ: Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Health Research; EMR: Electronic Medical Record; MOA: Medical Office Assistant; NP: Nurse Practitioner; GAD: Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Introduction

Patients and healthcare providers routinely share data in the form of personal health information or test results as part of usual care. Traditionally, most data sharing has occurred in-person. However, the technological landscape for sharing, integrating, and analyzing data has constantly evolved and escalated since the onset of COVID-19 [1]. The increased mobilization of technology to support virtual care during the pandemic has the potential to both enhance or limit patient-provider data sharing, but research is limited as to the nature of data sharing and how this may have changed. Several studies examined mental/behavioral health professionals’ views on patients’ data sharing with providers [2-4]. Concerns were identified around privacy, stigma, fear of disclosure, trust, and motivations for care seeking (e.g., prescription refill). Similarly, studies on health-data sharing explored issues of privacy and trust when data are shared outside the patient-provider relationship; for example, provider sharing of data with researchers, insurance companies, or government [5-7].

A recent scoping review found that sharing patient-generated data collected outside of clinical settings fostered patient-provider communication and improved providers’ understanding of their patient’s health. However, while patients wanted their providers to be interested and involved in responding to these data, providers had varied interest and were not always able to accommodate due to challenging workflows [8]. The scoping review papers primarily focused on specific diseases (e.g., diabetes), were completed years before the pandemic, were not specific to virtual care, and did not address geographic location. In a pre-pandemic qualitative study, rural primary-care providers had positive attitudes about patient remote access to test results and health-record data to enhance healthcare decision-making, and cited preferences for patient-generated clinical data such as menstrual periods, blood pressure (BP), chronic-disease symptoms, and weight (Blinded for Review).

We found no studies that examined healthcare providers’ datasharing practices with patients using virtual (non-direct contact) formats [9]. The purpose of this study was to examine healthcare providers’ current data-sharing practices, perceptions, and experiences. We were most interested in learning about the types of patient-generated data they used in patient care, the features/ tools/processes used in data sharing, and barriers and facilitators to data sharing.

Methodology

Design

We conducted this qualitative study, using a naturalistic inquiry approach [10]. The study was part of a larger mixed-methods study examining data sharing and personal health records among primary care clinics in a rural region of British Columbia.

Participants and setting

Following ethics approval by a University Behavioral Ethics Board (# anonymized for review), providers participating in the larger personal-health-record study along with primary care providers identified by the research team’s regional digital liaison were sent an email invitation to participate in Focus Groups (FGs). Of sixteen providers invited, two were unable to attend due to scheduling conflicts. All providers had either used technology for data sharing before, or as a response to, the COVID-19 pandemic, or as part of the larger personal-health-record study. Once a mutually convenient time was determined for the FG, links to the online meeting, a consent form and a short survey were emailed to participants by a research team member (A2).

Data collection

Prior to FG sessions, all participants consented, received a FG discussion guide, and completed a short online survey that asked about length of clinical practice, comfort with technology use, datasharing platforms used, and provider category. FGs were held Nov- Dec 2020 and lasted approximately one hour. They were facilitated by an experienced team member (A1, A2) or researcher, with other team members keeping notes of the sessions (A3, A4); all but one researcher was female, and all had advanced educational preparation (PhD, MSc, MD). Six participants had existing relationships with researchers through previous research. All participants were made aware of the study purpose and researchers’ interest in the topic. A semi-structured discussion guide was used containing questions about participants’ practices and experiences of sharing data and communicating with patients; digital/electronic tools, features and functions they used in sharing data/communicating with patients, and barriers and facilitators to data sharing. All focus groups and interviews took place over a videoconferencing software (Zoom), with the option to dial in by telephone [11]. Participants received e-mail instructions for connecting to Zoom and the Research Coordinator’s contact information for technical support

Analysis

Focus group audio recordings were transcribed automatically using NVivo Transcription (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) and accuracy checked against the recordings by a research team member (A2). Transcribed data were analyzed thematically [12]. Two research team members (A1, A2) and a research assistant performed open coding of data from the first two transcripts for units of meaning consisting of words, phrases, or paragraphs. Similar codes were clustered into themes and subthemes to generate a preliminary coding schema. A research assistant used the schema within NVivo (Version R1), a qualitative management software program, to guide the coding of FG data with continual refinements and consensus of the research team to ensure accounting of all data. Demographic data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. The researchers kept field notes and engaged in ongoing reflexivity and reflection to avoid influencing the research process including data analysis. We followed the consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Health Research (COREQ) [11].

Result

Fourteen providers from seven clinics participated in six FGs over three months, with one to four participants in each group. Providers were primarily female (n=11) and physicians (n=9) with an average practice length of 9.75 (SD 5.12) years. Additional providers included a nurse practitioner (n=1), midwife (n=1), and office managers (n=3).

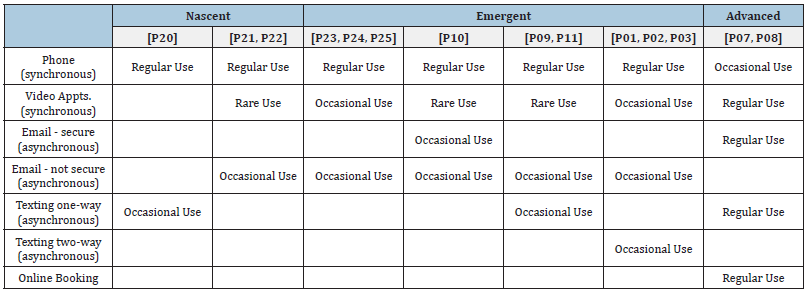

Data sharing since the pandemic

Providers varied in their data-sharing practices; this primarily reflected their digital-tool-use maturity levels and whether those tools were interconnected within their Electronic Medical Record (EMR). The number, frequency, and type of digital (synchronous and asynchronous) tools they used determined their maturity levels (Table 1) which were described according to three levels: nascent (n=2), emergent (n=11), advanced (n=1). Nascent involved use of few digital tools for sharing data with patients, with a predominance of one modality only (typically synchronous telephone), and no EMR integration of those tools. A nascent provider summarized their technology use: “as things started getting busy again, we just gravitated to the easiest thing, which became the telephone … we did explore using [EMR integrated] virtual care ... but we were denied that by the health authority because there was a cost attached to this.” [P20]

Emergent digital tool use involved regular use of more than one digital tool for sharing data with patients, with data tools compatible with, but not fully integrated within the EMR (e.g., unsecured email or Ring Central), and requiring manual data entry into the EMR. An emergent provider user summarized their combination of digital tools and developing integration: “we don’t formally have a platform. RingCentral is our sort-of peripheral emergency phone number … and sometimes people will send us some pictures through that, certainly appreciating that it’s not secure, but we don’t have a secure messaging system... A lot of it will just simply be good old-fashioned texting, emailing information.” [P02]

Advanced digital use involved routine use of a robust suite of digital tools for sharing data that were fully integrated within the EMR. The only advanced-level practice provider summarized their combination of modalities: “Health Myself [Patient Portal by Pomelo Health Canada] is our platform for online booking, messaging with patients, uploading documents, forms. And for telephone we have RingCentral, which is also a platform that we might use for video conference… Now most patients are using the Health Myself Pomelo Video Conference.” [P08]. The Medical Office Assistant (MOA) from this advanced practice described the patient portal as the place where all interactions between patients and providers occurred, resulting in full data integration.

Providers also varied in their perceptions of changes in their data sharing with patients during COVID-19. Some providers perceived little change in how they were getting patient-generated data, as one provider stated, “I don’t think there’s been any revolutionary change in how I’m getting that information from the patient”.[P23] Other providers perceived changes in the volume of data sharing with patients. According to one provider, “if anything, we’re getting less information. Not related to technology, just to the fact that people are still avoiding to come in and still trying to stretch out appointments, but it has nothing to do with technology.” [P24] A Nurse Practitioner (NP) reinforced the challenges of patients’ data sharing with providers, “I think we would get more of that information from people if there was an easier way to get it to us.” [P20]

Electronic data sharing value by modality

All providers used synchronous and asynchronous modalities for data sharing with patients. However, there was variability in how they combined and used them in patient care (Table 1)

Telephone data sharing:All providers used telephone for synchronous data sharing but to differing degrees, with greatest use among nascent digital users, frequent use among emerging users, and limited use among advanced digital tool providers. Nascent digital provider users, however, described sharing several types of data using this modality. Although one nascent provider described his phone-related data sharing as, “mostly it’s just historical data that patients are giving me,” [P22] both nascent and emergent technology providers described completing standardized assessment forms (e.g., Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9’s], Generalized Anxiety Disorder [GAD-7’s]) with patients “over the phone” [P20] or having patients complete them ahead of a phone appointment. [P25] Since COVID-19, providers were increasingly having patients collect biometric data (e.g., blood pressure, weight) at home and discussing results during their phone appointments. Several of these providers reported occasionally supplementing data sharing through other modalities, such as email (secure and unsecure) or text, as needed.

The advanced technology providers used telephone minimally because they viewed other options as superior for sharing data. Both emergent and advanced technology users noted telephone data sharing limitations that included not being able to see physical concerns and behaviors and having to rely on asking the right questions without supplemental visual cues.

Video data sharing:Video was used to a lesser extent among most providers compared to telephone even though several providers expressed preferences for video because of the enhanced visual data sharing and their perceptions of better overall appointment quality compared to using telephone. Advanced technology providers encouraged patients to “use zoom videoconferencing, when possible,” [P08] but also used telephone to respect individual patient preferences. Providers found that video was particularly helpful with diagnosing, such as with dermatologic concerns. An emergent technology provider described using video to maximum advantage by having patients provide the visual data needed for a virtual examination:

I miss the physical examination... I have been able to ask patients to move different appendages and take a look at skin lesions or at least see how they appear to be. And I like that about the video conferencing platform when possible. But I still don’t feel confident that even in those cases that there’s been a thorough physical exam.” [P24]

SMS/Email/Using patient portal data sharing:All providers used asynchronous modalities for data sharing but there was considerable variability in the nature and extent of use across provider digital-tool maturity levels (Table 1).

Nascent and emergent technology providers who made limited use of asynchronous data sharing spoke of it as the exception rather than the rule, reserving use for very selective patients, circumstances, and data types. These providers expressed discomfort, even dislike, of asynchronous modalities for non-specific issues such as a patient’s medical history, for “clinical things” [P25], “for care” [P24] and even told patients to send them anything they wanted by email but they “wouldn’t necessarily respond” [P22]. Many discouraged patients from using these modalities. Other providers thought that using texting to share data was less valuable than telephone; one emergent provider elaborated, “I still feel like a text back and forth communication with someone gives me even less information than when talking to them on the phone, because now I’ve lost tone; it’s maybe super useful for a very simple thing.” [P10

Some emergent providers described asynchronous modalities as appropriate for sharing data that were “static” or “concrete” such as BP or glucose logs or pictures of moles, because “if I actually want to know what’s going on, I have to speak to the person so we can have a two-way communication.” [P11] Other emergent providers also used asynchronous modalities for follow-up, “When I have to go through the school counselor to reach out to the youth to figure out when’s the next follow up or what to do with this and that. And I try to be clear that it’s an email that I don’t check often and that it’s just for these specific clarifications.” [P24].

However, some providers were cautious about asynchronous modalities as follow-up without considering the patient needs. One emergent provider noted, “I use the clinic MOAs to email someone back and just give them a bit of a plan, but really I don’t like to do that without clarifying that the patient understands it and that we’ve got a plan B, so I’m not very keen on firing things off without actually talking to someone.” [P11]

Despite some providers discouragement of patients’ use of asynchronous data sharing, it was helpful in some cases, such as submitting a photo, so the provider could determine if the patient needed to be seen in person. In contrast, two clinic groups were frequent users of interactive two-way texting with their patient populations (Table 1).

Table 1: Digital tool maturity.

Emergent digital providers from a maternity practice described regular use of texting with their maternity patients over a range of data types (e.g., pictures of baby rashes; maternal logs, updates on labor progress). They found texting superior and more efficient than a video call for managing patients despite it not being a secure messaging option. The advanced digital providers, regularly engaged in secure two-way texting and messaging for data sharing with patients that complemented synchronous data sharing. These providers tailored the asynchronous modality they used according to the type of data being shared. For example, the provider described texting with a patient with diabetes being started on insulin. For other types of data, like BP, that required routine monitoring, the provider had patients keep logs uploaded to the secure messaging system; they would then respond with next steps.

This practice also used online booking and emailed questions using asynchronous modalities to obtain patient-generated data that complemented synchronous sessions: “if someone is making an online booking and saying, oh, I’m concerned because I have a mole on my cheek […], I will say back using a secure message, can you attach a picture of your lesion and put a ruler on it so she can see how big it is?” [P07] Although providers were cautious about security issues when called on to share patient data using an unsecure environment, such as personal email, providers perceived patients were not concerned about security and freely sent data using unsecure modalities (email, text).

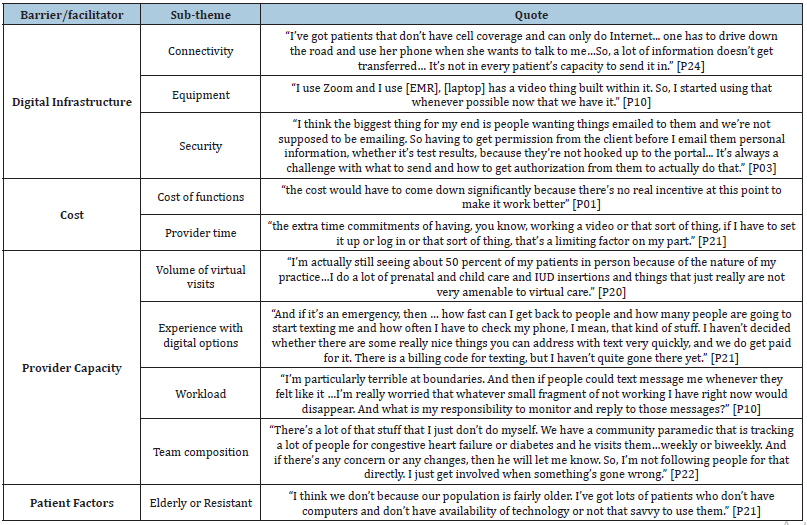

Barriers and facilitators

Despite the value of data sharing, nascent and emergent digital providers expressed barriers to fully integrating electronic data sharing into their clinics including digital infrastructure, cost, provider capacity, and patient factors (Table 2). In contrast, advanced digital providers had overcome these barriers prior to the pandemic.

Digital Infrastructure:Digital infrastructure had a major influence on provider responses to electronic data sharing with patients, although the influence was variable across providers and dependent on both the clinic and patient’s geographic location in the rural study region. Poor connectivity for patients, and in some cases the providers themselves, was cited as a major barrier to adopting electronic data sharing. While a number of providers supported video use because of its expanded data-sharing capacity beyond the telephone, equipment availability also influenced use. For example, despite the availability of Wi-Fi for phone connectivity, an NP (nascent digital provider) described their struggles with “the technology in our office” and their lack of office laptops equipped with audio and visual functionality that limited them to the telephone.

Cost: Cost was a recurring barrier for many providers. With each additional digital tool came additional monthly costs. One emergent provider noted some “amazing platforms” [P01] that had attractive functionalities (health history, easier texting/ messaging, scheduling, capacity to send educational resources) but the monthly cost per provider was prohibitive. Another aspect of cost was provider time. A number of providers expressed concerns about the burden of responding to asynchronous text messaging as a barrier to using this data-sharing modality.

Provider factors/capacity:Provider factors influenced both data-sharing practices and modalities for data sharing (Table 2). Factors included volume of in-person visits, unknowns about asynchronous data sharing, workload, and team composition. Providers who continued to see a large proportion of their patients in person (nascent and emergent digital users) were less motivated to use virtual data sharing or to consider other options. For example, one provider who still saw half of their patients in person, viewed virtual modalities as inappropriate for the patient populations served. In contrast, more advanced digital users, who offered most of their care virtually, were highly motivated to engage in electronic data sharing. One provider whose practice, was “nearly 70 percent videoconference or virtual care in general” [P08] used all virtual modalities and encouraged patients to use them routinely (e.g., secure messaging for data-sharing).

Table 2: Details regarding barriers and facilitators to electronic data sharing.

Also expressed were concerns related to lack of experience with digital options, the potential for missed timely urgent patient data, or uncertainties about the full potential of these modalities. Familiarity with low-tech options like the telephone, and userfriendly and easy-to-use features that saved time were important to providers and served as barriers to expanding data-sharing options. Provider willingness to trial-and-error options was also critical for expanding or improving data sharing. For example, transition was easier for advanced digital users who had experimented for five years with a multi-modality, fully integrated system that permitted secure synchronous and asynchronous modalities. Other factors influencing virtual patient-provider data sharing were provider workload and the clinical team’s make-up (Table 2). For example, one nascent digital user had allied health professionals, who had direct contact with patients in the community, collect data from patients and communicate back, obviating the need for exploring direct electronic data-sharing options with patients.

Patient factors:Patient factors also influenced providers’ datasharing practices. Perceived patient capacity, comfort, preference, and technology availability were crucial influences on providers’ greater use of telephone. Nascent providers spoke about their predominantly older patients who lacked technology, email access, and capacity to support video use. Other providers reported that patients were unwilling to accept video appointments. When offering the choice of appointment modality, they had “very few patients who take me up on it [video]”. [P10] Some providers spoke of strong patient resistance to video visits even when there was hands-on support offered. One emergent provider noted that, despite encouraging patients to use an app for specific tracking questionnaires, there was little uptake. In contrast, advanced digital users endorsed videoconference over telephone when possible. These providers described educating patients to share data using the patient portal versus unsecure email.

Discussion

Examining healthcare providers’ data-sharing practices with patients is timely and relevant given the COVID-19 push to virtual care with its inherent changes in data-sharing that traditionally occurred during in-person visits. We found that data sharing was highly variable across providers primarily reflecting the practice/ provider’s maturity level (nascent, emergent, advanced) in digitaltool use. Most providers were in process with digital usage and integration. Although not specific to data sharing, Jimenez and colleagues [13] found in their review that technology was used in only 38% (14 of 37) of papers as part of multicomponent interventions to enhance primary care. Of those, only 5 were aimed at patients and used web-based online portals and messaging platforms as digital tools that facilitate data sharing.

Synchronous data sharing by telephone, was the most common practice across providers. Telephone, while not always the most efficient data-collection approach (e.g., completion of forms), serves to enhance communication and patient-provider relationships and is considered the cornerstone to successful virtual-care implementation [8,14]. Video was a preferred option for some providers; yet, connectivity issues and lack of broadband internet, well documented in rural communities, were ongoing constraints (Blinded for Review). These persistent barriers negatively impact access and service equity for rural-living citizens. We found divergent provider perspectives on the role and value of asynchronous data sharing.

The majority had reservations about email and texting due to lack of data security, lack of simultaneous data entry into the clinic’s EMR system, perceived lack of fit/appropriateness for clinical issues, and its disconnection from the patient’s larger clinical picture. These findings resonate with a pre-pandemic United Kingdom-focused ethnographic study of alternatives to face-to-face appointments in general practice in which face-to-face was considered the ideal and non-face-to-face interactions (phone, email) were associated with uncertainties related to suitable patients/health issues and only offered as a last resort when no appointments were available [15].

Providers who regularly used email and texting, however, described not only convenience but better chronic-disease management (e.g., diabetes, hypertension). Mabeza et al. [16] similarly found that synchronous primary-care telemedicine that included asynchronous components for data transmission was as effective as in-person care in managing diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. Swiss providers reported using two-way email communication to respond to patients’ questions (82%) and change appointments (72%) and used text messages to follow patients’ health conditions [17]. Although Canadians desire access to more interactive electronic services, few Canadian primary care providers offer them to patients [18]. In a recent Canadian primary-care study, patient participants overwhelmingly preferred asynchronous communication due to convenience and time to think and respond [19].

We found trade-offs between provider capacity (time, workload/flow, resources) and technology/infrastructure considerations that influenced providers’ data-sharing practices. Consistent with findings from a recent Canadian scoping review, incompatible clinical workflows with patient desire for responses to asynchronous data-sharing, and lack of applicable technology/ infrastructure were barriers to expanded virtual primary care services during and following COVID-19 [20]. Only one provider in our study integrated synchronous and asynchronous datasharing. Despite similar barriers to other providers, this practice’s willingness to experiment with various systems as early adopters of digital technologies allowed them to reach full capacity with data-sharing (Blinded for Review).

Nascent and some emergent digital use providers likely fail to perceive how investing in technology promotes appointment efficiency and improves workflow, such as saving synchronous appointment time for collecting data that could be transmitted asynchronously. While many believed that digital options have merit, investing in these options would require financial incentives, mandates, or both to incorporate them into practice. Training in digital tool use and team-based care models, integration of data into EMRs, and change support for providers is needed so that digital options become easy, seamless, and result in better outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

We included a range of healthcare providers from various types of clinical practices (e.g., walk-in, family practice) and with various levels of technology adoption, thus enhancing the transferability of the findings. However, this is a convenience sample of rural providers, identified as using technology in their clinics, and may not have represented the data-sharing practices of providers who had not adopted technology or practice in urban settings. Provider’s perspectives of patients in the data-sharing process may not represent the patients’ perspectives and is a priority for future research. Data were gathered during the pandemic which may not reflect “usual” data-sharing practices but adaptations in response to COVID-19 pandemic requirements for distancing. Whether these practices persist over time or evolve would be a fruitful area of study

Conclusion

Overall, healthcare providers’ electronic data-sharing practices with their patients varied greatly and reflected their digital-tooluse maturity levels, connectivity, uncertainties, and whether those digital tools were interconnected within their EMR. Trade-offs between provider capacity (e.g., workload, workflow, care team composition) and clinic digital infrastructure (type and level of sophistication of digital health tools and technologies) influenced data-sharing practices. Many barriers and facilitators were identified and offer opportunities for enhancing data flow between patients and providers for optimal care and outcomes. It would be valuable to the ongoing evolution of electronic data-sharing practices in healthcare to reexamine data-sharing practices and identify best practices in our post-pandemic world.

References

- Adanijo A, McWilliams C, Wykes T, Jilka S (2021) Investigating mental health service user opinions on clinical data sharing: Qualitative focus group study. JMIR Mental Health 8(9): 30596.

- Ivanova J, Grando A, Murcko A, Christy Dye, Darwyn Chern, et al. (2020) Mental health professionals’ perceptions on patients control of data sharing. Health Informatics 26(3): 2011-2029.

- Grando A, Ivanova J, Hiestand M, Darwyn Chern, Jonathan Maupin, et al. (2020) Mental health professional perspectives on health data sharing: Mixed methods study. Health Informatics J 26(3): 2067-2082.

- Shin GD, Feng Y, Gafinowitz N, Jarrahi MH (2020) Improving patient engagement by fostering the sharing of activity tracker data with providers: A qualitative study. Health Info Libr J 37(3): 204-215.

- Perera G, Holbrook A, Thabane L, Foster G, Willison DJ (2011) Views on health information sharing and privacy from primary care practices using electronic medical records. International Journal of Medical Informatics 80(2): 94-101.

- Tierney WM, Alpert SA, Kelly C, Jeremy CL, Eric MM, et al. (2015) Provider responses to patients controlling access to their electronic health records: A prospective cohort study in primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine 30(1): 31-37.

- Stone MA, Redsell SA, Ling JT, Hay AD (2005) Sharing patient data: Competing demands of privacy, trust and research in primary care. British Journal of General Practice 55(519): 783-789.

- Lordon RJ, Mikles SP, Kneale L, Uba Backonja, William BL, et al. (2020) How patient-generated health data and patient-reported outcomes affect patient-clinician relationships: A systematic review. Health Informatics Journal 26(4): 2689-2706.

- Canada DH (2021) HiQuiPs: Introduction to virtual care-general principles-Digital Health Canada.

- Sandelowski M (2010) What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health 33(1): 77-84.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19(6): 349-357.

- Richards L, Morse JM (2012) Readme first for a user’s guide to qualitative methods. (3rd Edn), University of Utah, Sage publishing, USA, pp: 336.

- Jimenez G, Matchar D, Koh CHG, Kleij R, Chavannes NH (2021) The role of health technologies in multicomponent primary care interventions: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 23(1): 20195.

- Li J, Roerig M, Saragosa M (2020) A rapid review prepared for the Canadian foundation for healthcare improvement.

- Atherton H, Brant H, Ziebland S, Tania P, Chris S, et al. (2018) Alternatives to the face-to-face consultation in general practice: Focused ethnographic case study. The British Journal of General Practice 68(669): 293.

- Mabeza RMS, Maynard K, Tarn DM (2022) Influence of synchronous primary care telemedicine versus in-person visits on diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Primary Care 23(1): 1-10.

- Dash J, Haller DM, Sommer J, Perron NJ (2016) Use of email, cell phone and text message between patients and primary-care physicians: Cross-sectional study in a French-speaking part of Switzerland. BMC Health Serv Res 16(1): 549.

- Affleck E, Hedden D, Osler G (2020) Virtual care: Recommendations for scaling up virtual medical services.

- Stamenova V, Agarwal P, Kelley L, Michelle P, Ivy W, et al. (2020) Uptake and patient and provider communication modality preferences of virtual visits in primary care: A retrospective cohort study in Canada. BMJ Open 10(7): 037064.

- Vera K, Challa P, Rebecca Liu H, Eunice L, Emily Seto, et al. (2021) Virtual primary care implementation during COVID-19 in High-Income countries: A scoping review. Telemedicine and e-Health 28(7): 920.

© 2022 Selena Davis. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)