- Submissions

Full Text

Trends in Telemedicine & E-health

Is Telemedicine the Future of Global Health?

Shir Sara Bekhor*, Reis APFA, Doerksen DB, Fortunato GD, Lemieux P and BeyY

Department of Medical-Surgical Physiopathology and Transplantation, University of Milan, Italy

*Corresponding author: Shir Sara Bekhor, Department of Medical-Surgical Physiopathology and Transplantation, University of Milan, Via Festa del Perdono 7, 20122 Milan, Italy

Submission: February 4, 2022; Published: February 14, 2022

ISSN: 2689-2707 Volume 3 Issue 2

Opinion

Telemedicine is the practice of medicine using technology to deliver healthcare remotely. While it’s already implemented in a variety of ways, it still shows tremendous potential to grow and may serve as a solution to existing problems. Telemedicine provides a means for health practitioners to interact with experts/patients around the world, facilitating the transmission of medical information and allowing continuous care irrespective of location. These programs show direct improvements in healthcare outcomes, but beyond that, they also significantly reduce treatment and travel costs for the patient, enabling the delivery of healthcare to resource-poor and remote populations. Rural communities face several barriers to healthcare access such as remoteness to tertiary care centers, resource scarcity, difficult emergency transfers, limited access to physicians and specialists and limited training of medical and nursing staff [1].

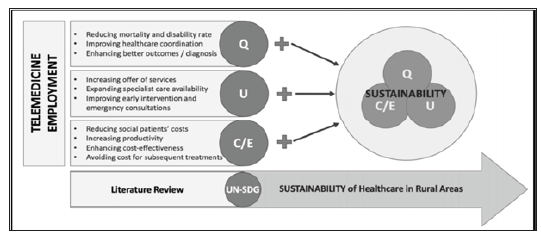

This so-called “rural penalty”, disadvantaging rural residences due to the distance between them and a specialist healthcare provider, can be solved by novel telemedicine approaches. Telemedicine strategies that promote access to healthcare in rural areas enhance the United Nations’ Sustainable Developmental Goals 3 (“ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages”) and 10 (“reduce inequality within and among countries”). According to the WHO, a healthcare intervention is sustainable if it respects one or more of the so-called sustainability pillars for healthcare which are: reducing healthcare costs (C), increasing healthcare efficiency (E), enhancing healthcare utilization (U) and improving healthcare quality (Q) [2] (Figure 1). However, despite significant improvements achieved by the diffusion of telemedicine, there are substantial obstacles that must be overcome in order to improve healthcare access in rural areas. These include the lack of equipment, human resources, proper public health policies and adequate training, along with poor infrastructure, a significant technology gap and low literacy [3]..

Figure 1: Demonstrates which sustainability variables are enhanced by telemedicine employment as a means of delivering healthcare in rural areas.

Without proactive efforts to ensure equity, the current widescale implementation of telemedicine may increase disparities in healthcare access for vulnerable populations where poverty and lack of education are widespread [4]. A subsequent obstacle to the provision of healthcare is disparate cultural views with regards to western medicine. Okoroafor et al. state that most Africans are very religious, and this extends to their understanding of their health matters and health‑seeking behavior [5]. It’s important to consider that telemedical services are most effective when the external consultant is familiar with the local culture and settings, including the resources available for care, the structure of the local healthcare system, and cultural conditions or customs that affect health and local disease epidemiology. For instance, in the domain of teleneurology, the differential diagnosis of a seizure varies substantially by region, and proper knowledge of the local setting is crucial [6].

Thus, the success and long-term sustainability of telemedicine strategies depend on the presence and competence of local healthcare authorities, and education should make up an essential portion of this process [7]. Telemedical programs run by foreign organizations must collaborate with local healthcare authorities, not only to bridge cultural barriers, but to avoid a situation where these remote services are over-relied upon. Medical aid by means of telemedicine could decrease political incentive to allocate funds for the development of local services [5], and perhaps undermine the future of medical training in these regions. Moreover, while telemedicine can and should be a fundamental tool in global health, it cannot and should not replace the sanctity of a real patientphysician relationship [8]. In-person evaluation and physical contact are still critical for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. The health system and individual patients will see the greatest benefits when telemedicine becomes an integral part of health service delivery, instead of a standalone approach.

Telemedicine has rapidly expanded around the world and proved its necessity during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic by allowing patient-doctor visits to occur online, thus removing the risk of transmitting the virus. In fact, it has already shown prominent improvements in health outcomes in the fields of infectious diseases, maternal health, chronic diseases and preventive health [3], which account for a great portion of the global burden of disease. Rural populations should also have access to these benefits, but much remains to be done. Partnerships between governments and NGOs can secure funding, establish leadership, develop infrastructure and create protocols that establish a standard regulations in order to implement telemedicine in rural areas. Perhaps more importantly, education must be an integral part of the process, which includes training of healthcare providers (cultural barriers, local settings, etc.) and educational programs for the local communities on healthseeking behavior and digital literacy.

References

- Annie M, Patrick S, Catherine B, Raffi K, Jean-Marc C (2012) Space medicine innovation and telehealth concept implementation for medical care during exploration-class missions. Acta Astronautica 81(1): 30-33.

- Palozzi G, Irene S, Antonio C (2020) Enhancing the sustainable goal of access to healthcare: Findings from a literature review on telemedicine employment in rural areas. Sustainability 12(8): 3318.

- Clemens K, Betancourt J, Stephanie O, Susana MVL, Inderdeep KB, et al. (2019) Barriers to the use of mobile health in improving health outcomes in developing countries: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 21(10): 13263.

- WHO Global Observatory for eHealth (2011) MHealth: New Horizons for Health through Mobile Technologies: Second Global Survey on eHealth. World Health Organization, pp. 102.

- Okoroafor IJ, Chukwuneke FN, Ifebunandu N, Onyeka TC, Ekwueme CO, et al. (2017) Telemedicine and biomedical care in Africa: Prospects and challenges. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice 20(1): 1-5.

- Dorsey ER, Alistair MG, Melissa RH, Gretchen LB, Lee HS (2018) Teleneurology and mobile technologies: The future of neurological care. Nature Reviews Neurology 14(5): 285-297.

- Nouri S, Khoong EC, Lyles CR, Karliner L (2020) Addressing equity in telemedicine for chronic disease management during the Covid-19 pandemic. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery 4:

- Kim T, James EZ (2021) Realizing the potential of telemedicine in global health. Journal of Global Health 9(2): 020307.

© 2022 Shir Sara Bekhor. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)