- Submissions

Full Text

Trends in Telemedicine & E-health

Acceptance and Cognitive Restructuring Intervention Program (ACRIP) in Telemedicine on the Symptoms of Internet Gaming Disorder and Psychological Well-Being of Adolescents

Georgekutty Kochuchakkalackal Kuriala1,2*

1The Graduate School, University of Santo Tomas, Philippines

2The College of Medicine, Emilio Aguinaldo College, Philippines

*Corresponding author:Georgekutty Kochuchakkalackal Kuriala, The Graduate School, University of Santo Tomas, Philippines

Submission: January 17, 2020; Published: February 19, 2020

ISSN: 2689-2707 Volume 2 Issue 2

Abstract

The Acceptance and Cognitive Restructuring Intervention Program (ACRIP) has been proven efficacious in existing studies to reduce the symptoms of Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) and improve the psychological well-being of adolescents. IGD has recently been recognized as a mental health condition by the World Health Organization as it becomes an emerging issue of significant public health concern. Empirical evidences associating IGD with poor psychological well-being are increasing. This study recommends that telemedicine adopt the ACRIP in addressing the symptoms of IGD. The ACRIP was developed and tested efficacious through the use of sequential exploratory research design and randomized controlled trial. Internet Gaming Disorder (IGDS9-SF) and Ryff’s Psychological well-being (PWB) scales were used to measure the severity of the gaming disorder and state of psychological health of the experimental and control groups. Statistical analysis using MANOVA on post-test mean scores on IGD and PWB of the experimental group showed a significant difference which suggested that the ACRIP is efficacious in reducing the symptoms of IGD and improving the psychological well-being of selected adolescents included in the studies and is culture-free. Cohens d test showed the large effect of the ACRIP

Keywords:Acceptance; Cognitive restructuring; Internet gaming disorder; Psychological well-being; Telemedicine

Introduction

“Gaming disorder”, the official nomenclature given by the World Health Organization

(WHO) to compulsive online or offline gaming, was recently recognized as a mental health

condition. It was included in the WHO’s 11th International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11)

released mid-2018 and characterized as “a pattern of persistent or recurrent gaming behavior

(‘digital-gaming’ or ‘video-gaming’), which maybe online (i.e., over the internet) or offline,

manifested by: (a) impaired control over gaming (e.g., onset, frequency, intensity, duration,

termination, context); (b) increasing priority given to gaming to the extent that gaming takes

precedence over other life interests and daily activities; and (c) continuation or escalation

of gaming despite the occurrence of negative consequences.” These manifestations whether

continuous, episodic or recurrent, must be present at least in the last 12 months to be

significant for diagnosis. If severe symptoms and all diagnostic criteria are present, the length

of time may be shorter. The ICD is used by medical practitioners around the world to diagnose

conditions and by researchers to categorize conditions [1].

In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) recognized excessive online gaming

due to its potential to becoming a public health threat and referred to it as Internet Gaming

Disorder (IGD). To aid clinicians, it defined the nine preliminary diagnostic criteria in the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5th edition (DSM-5), last updated in 2013, as:

A. Pre-occupation with internet games,

B. Withdrawal symptoms,

C. Tolerance or the need to spend increasing amounts of gaming time,

D. Unsuccessful attempts to control participation in internet games,

E. Loss of interest in previous hobbies and entertainment,

F. Continued excessive use of internet games despite knowledge

of psychosocial problems,

G. Deceived family members, therapists or others on the amount

of time spent gaming

H. Used internet games to escape, and

I. Harmed or lost a significant relationship, job, or educational or

career opportunity. Five of these nine criteria must be present

over a 12-month period for diagnosis and should lead to a

significant impairment and clinical distress [2].

To further expound on the negative outcomes of IGD, IGD

is significantly associated with self-harming behaviors due to

uncontrollable pre-occupation with gaming [3]. Its psychological

consequences include sacrificing sleep, other pastime activities,

socializing and relationships [4] and jeopardizing school and work

performances. It also causes health problems like eye strain, carpal

tunnel syndrome, back strain and repetitive stress injury in some

cases. Given the wide range of existing and possible destructive

effects of IGD [5] which allow its behavior to be classified as

pathological based on the APA’s established clinical standard [6],

IGD may require professional treatment [7].

Based on review of existing literature, there has yet to be

an established effective intervention program to address IGD

as review of treatments on 36 studies employing Cognitive

Therapy seem to lack cognition-based measures [8]. There is

also no strong evidence of an effective intervention, short or long

term, due to weaknesses in methodologies of diagnosis and post

treatment/follow through. And there is very limited evaluation

on the efficacy of various psychological interventions applied on

adolescents [8,9]. To fill the gaps in the on-going research for an

efficacious intervention program to address IGD, the “Acceptance

and Cognitive Restructuring Intervention Program” (ACRIP) was

developed with main objectives of reducing the symptoms of IGD

and improving the psychological well-being of selected adolescent

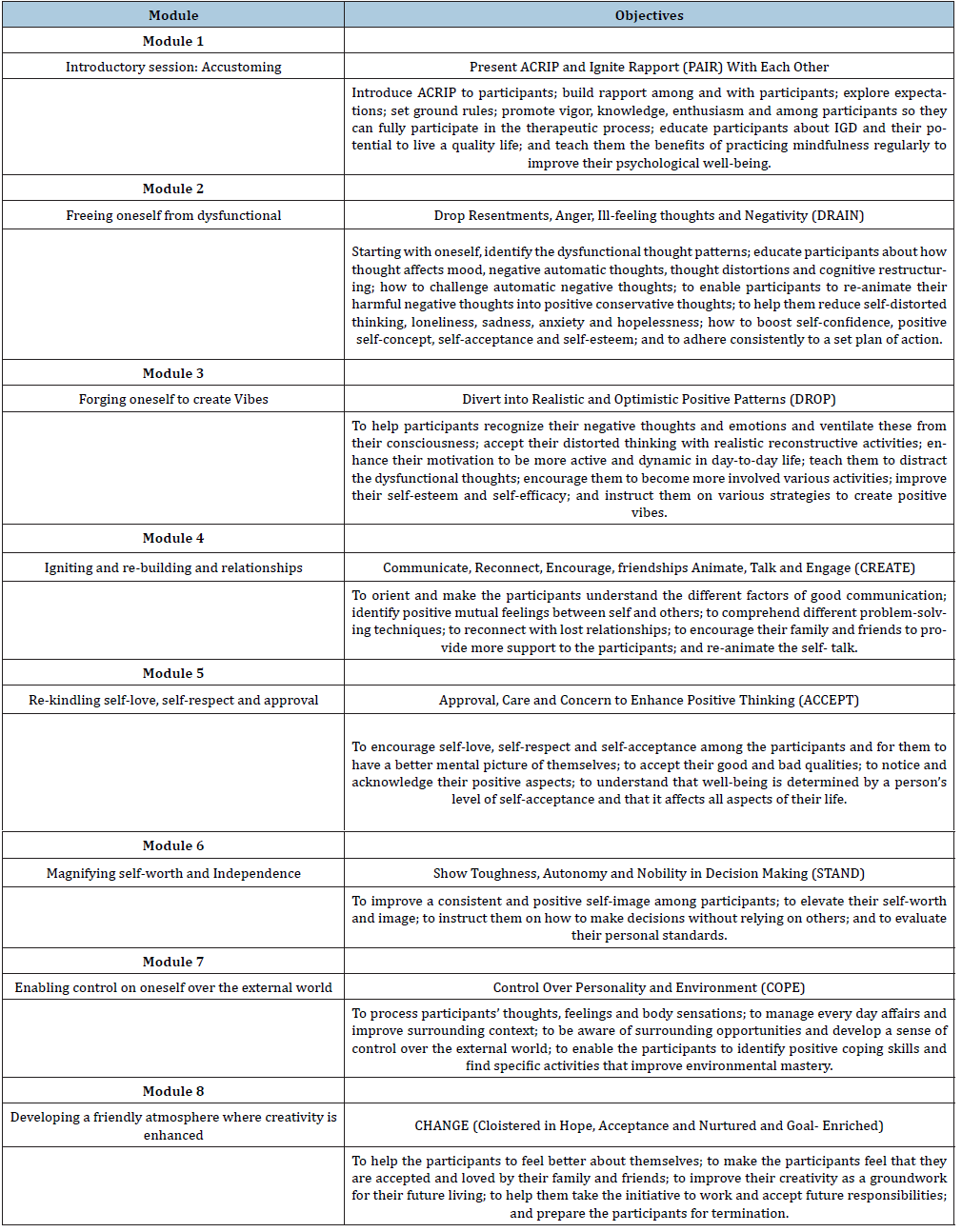

gamers in India. The eight-module intervention program (Table 1)

was expert validated, found efficacious and positively received by

the participants in the pilot and experimental studies [10,11]. This

confirmed that the modules developed for the program integrating

the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Mindfulness theories

were reliable, feasible, and efficacious for testing on a large base

of adolescents who are at risk of IGD. The hypotheses established

during its development and testing for efficacy included:

A. Negative cognition influences psychological well-being,

B. IGD predicts poor psychological well-being, and

C. The ACRIP as an intervention program is efficacious in

reducing the IGD risk level and improving the psychological wellbeing

of adolescents, and has a lasting benefit

The ACRIP, an eight-module intervention program which was

organized for completion within four weeks (three hours per

module, twice a week) was then subjected to an experimental study

to test the modules’ efficacy.

Process of Developing ACRIP

A study of existing related literature and current scenario were performed to assess the relevance, impact and potential of the issue at hand. After a correlation was established between IGD and psychological well-being and careful examination of its constructs, the intervention program ACRIP was developed by integrating the concepts of two cognitive theoretical models: Cognitive Behavioral model of Problematic Internet Use (PIU) and Mindfulness. The intervention aimed at reducing the symptoms of IGD experienced by the adolescents and improving their psychological well-being in order that they will function productively at home, in school and other areas of their life so as not to become a burden to society.

The Cognitive Behavioral model of PIU suggests that pathologic internet use results from “problematic cognitions coupled with behaviors that either intensify or maintain the maladaptive response” [12]. It proposes that maladaptive cognitions about the self and world are proximal sufficient causes of symptoms of IGD. Cognitive distortion intensifies an individual’s dependence to internet gaming [12]. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is then applied by experts to guide an individual to self-question, self-talk and to instill positivity in them. The ACRIP program focused on selfawareness, self-acceptance, identifying cognitive distortions and its root cause, and determining the CBT technique most suitable to counter the effect of and modify these unhealthy thinking patterns leading to cognitive restructuring.

The cognitive theory of Mindfulness by Ellen Langer states that mindfulness is “a flexible state of mind in which we are actively engaged in the present, noticing new things and sensitive to context” [13]. Moreso, mindfulness is both a state and a trait wherein the state is the behavior in a particular situation while the trait can incline a person to think and behave mindfully [13]. It promotes sensitivity to the environment and supports clearer thoughts and behaviors as it teaches individuals to become observant of and experience their thoughts and feelings. Having the trait to be mindful can spawn new outlook and encourage making upright decisions. The basic framework of the theory is that with appropriate interventions, mindlessness can be overcome [13]. A person can then change behavior aligned to one’s thinking. In this way, it can be said that negative cognitions can be overcome through cognitive restructuring.

A pilot study was undertaken, and the results were good indicators to conduct an experimental study. The mean scores and standard deviation values using the IGD and PWB scales, pre-test vs. post-test, showed decrease in the adolescents’ IGD level (from M=41.50, SD=2.17 to M=20.80, SD=2.15) and increase in PWB level (from M=125.90, SD=11.60 to M=420.30, SD=22.48) implying a reduction in IGD symptoms and improved psychological well-being after the feasibility study. For statistical analysis, the ‘Wilcoxon signed rank test’ was used to assess the pre and post test scores of the adolescents. The result showed that there is a significant difference in the pre-test and post-test scores of both IGD (Z=- 2.809, p =.005) and PWB (Z= -2.803, p=.005).

Further, the participants’ feedback during the pilot test period were obtained to improve ACRIP prior this experimental study was performed. The participants positively acknowledged, expressed fulfillment and appreciated the program. Generally, they reported having less withdrawal symptoms on internet gaming, improved level of concentration, interacted with others more, felt contented and were excited for future life plans. The ACRIP was subjected to content validation by 11 mental health experts other than those involved in the focus group discussions and was tested for inter-rater reliability. The experts used the standard evaluation guidelines which was an adapted form of the tool developed and used by United States Agency for International Development (USAID). After thorough evaluation, the experts graded the program with an overall score of ‘A’ unanimously affirming the soundness, relevance and feasibility of the ACRIP. On the interrater reliability test of ratings given by the experts, the ACRIP was found be consistent and reliable. The inter-rater reliability resulted to co-efficient of .78. The result of the experts’ validation gave the assurance that the program is reliable and predicts high chances of being efficacious in bringing about affirmative changes. Expert comments and recommendations on technical and conceptual aspects were considered in building the program structure prior to start of the experimental validation. The experts suggested reducing the time spent per module from three and a half hours to three hours to hold the attention of the participants enough to keep the momentum and for them not to become weary due to overactivity. The result of the study confirmed that the modules developed for the intervention program are reliable, feasible, and efficacious for testing on a larger base of adolescents who are at risk of IGD. The eight modules developed for the ACRIP, summarized as AFFIRME, and the objective of each module were briefly described in Table 1 [11].

Table 1: ACRIP modules and objectives.

With integration of advancements in information technology, electronic communications technology, telecommunications, computers and mobile technology with the field of medicine, the field of telemedicine came about as early as the 1960s using radio and telephone. Presently, with the emergence of new health conditions needing immediate diagnosis and treatment, the internet facility plays an important role in communication and in providing these services to patients’ real time.

Methods

Design and participants

A true experimental research method between two

independent groups as subjects was adapted to determine

the efficacy of the intervention program. A prior approval was

obtained from the Manila Med Ethics Review Committee to support

observance of ethical standards during the conduct of this study.

Forty (40) adolescents (N=40, M=14.00, SD=1.34) were chosen

from those who met the inclusion criteria. Twenty (20) adolescents

were randomly assigned to each of the experimental and control

groups. The participants were selected on the basis of the following

inclusion criteria:

A. Adolescent boys and girls,

B. 12 to 18 years old,

C. Currently enrolled in schools

D. Staying/living with biological parents/guardians and

E. Engages actively in playing any of the available internet games.

Of the 40 participants, there were more males than females;

males comprise 70% (N=28) while females were 30% (N=12).

There were also more adolescents captured in the 16-18 age range

(N=24) than in the 12-15 age bracket (N=16). Participants’ gaming

profile showed 80% were playing more than 30 hours per week.

Broken down: 40 hours and up (N=24, 60%), 30-39 hours (N=8,

20%), and below 30 hours (N =8, 20%). Informed consent was

obtained from the participants and their parents and guardians.

The study was carried out in consideration of confidentiality and

ethical issues.

Measures

Personal data sheet/Demographic Information Form (DIF)

The study perused a researcher-made personal data sheet/DIF to obtain the following socio-demographic and gaming profile of the respondents: age, gender, number of hours of internet gaming per week, length of gaming per session, frequently played game title and genre, years of experience internet gaming and family relations. The informed consent also forms part of the personal data sheet/demographic questionnaire.

Internet gaming disorder (IGD) scale

The IGDS9-SF assesses IGD’s severity and its detrimental effects by examining both online and/or offline gaming activities occurring over a 12-month period [14]. The IGD questionnaire consisting of nine questions represents the nine criteria of IGD as defined by DSM-5, e.g., Do you feel preoccupied with your gaming behavior?, Do you feel more irritability, anxiety or even sadness when you try to either reduce or stop your gaming activity?, Do you feel the need to spend increasing amount of time engaged in gaming?, Have you lost interests in previous hobbies and other entertainment activities as a result of engagement with the game?

Ryff’s psychological well-being (PWB) scale

Ryff’s Psychological well-being scale consists of 84 items dealing with how an individual feel about himself and his life [15]. This self-report scale was designed to assess an individual’s well-being at a particular moment in time within each of these six dimensions:

A. Autonomy (e.g. “Sometimes I change the way I act or think to

be more like those around me”),

B. Environmental mastery (e.g. “Most people see me as loving

and affectionate”),

C. Personal growth (e.g. “I am not interested in activities that will

expand my horizon”),

D. Positive relations with others (e.g. “When I look at the story of

my life, I am pleased with how things have turned out”),

E. Purpose in life (e.g. “Maintaining close relationships has been

difficult and frustrating for me”) and

F. Self-acceptance (e.g. “In general, I feel that I continue to learn

more about myself as time goes by”).

Procedures

The data for this study were gathered from: pre-experimental, experimental and post-experimental phase. During the preexperimental phase, the researcher conducted an information drive about internet gaming disorder and the importance of an intervention program in different secondary schools in India. Using the purposive sampling technique, adolescents were selected from among the students who satisfied the set inclusion criteria. Thereafter, they were informed and assured of the confidentiality of information involved in this study, asked to sign an informed consent including their parents/legal guardians and fill-out the IGD and PWB scales. Interviews and focus group discussions were conducted to obtain valuable information for this research. The participants selected for the experimental phase were designated into experimental and control groups and were introduced to the proceedings of the intervention program ACRIP prior to its execution. The control group did not receive the intervention program ACRIP. The program was completed in four weeks and the program was similarly administered to the control group after the post-test for ethical considerations. In the post-experimental phase, the scores before and after the intervention were subjected to statistical analyses for evaluation.

Result

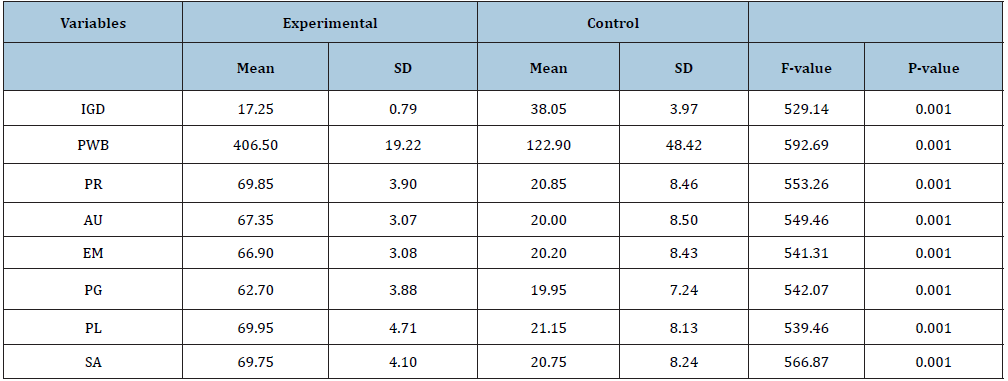

The study resulted in a remarkable change in the participants’

behavior as indicated by the post-test scores during statistical

analyses. The low score in IGD and high score in PWB measures

among the adolescents in the experimental group only shows that

some symptoms of the disorder have been eradicated or reduced

which validates that the level of IGD has been reduced and their

psychological wellbeing has improved. During pre-test, it was

noted that, on IGD measure, mean scores of both the experimental

and control groups are high and almost similar (Exp: M=38.50,

SD=1.40); Ctrl: M=38.45, SD=5.02). Pre-test mean scores of both

groups on PWB measure also reflected to be at almost the same

low level (Exp: M=126.10, SD= 18.96); Ctrl: M=124.60, SD=51.68).

Remarkably, for the experimental group, outcome of the post-test

on mean scores and standard deviation values showed relevant

decrease in IGD (Exp: M=17.25, SD=.79) and increase in PWB (Exp:

M=406.50, SD=19.22) levels. Post-test mean scores and standard

deviation values for the control group during post-test, for both IGD

and PWB measures remained more or less on the same level (IGDCtrl:

M=38.05, SD=3.97) and PWB-Ctrl: M=122.90, SD=48.42) as it

is during pre-test.

Overall result of MANOVA test on the difference in the mean

scores and standard deviation values of the experimental and

control groups during post-test shows significant differences (F

(7,32) =3626.206, p = .001).

Table 2: MANOVA results from the Post-test scores of the Experimental and Control Groups in terms of IGD and PWB

(between subject effects).

Legend: SD: Standard Deviation; IGD: Internet Gaming Disorder; PWB: Psychological Wellbeing; PR: Positive Relations;

AU: Autonomy; EM: Environmental Mastery; PG: Personal Growth; PL: Purpose in Life; SA: Self-Acceptance.

Table 2 presents the effect of ACRIP using variance analyses in MANOVA between subjects. Results point out that the significant difference on post-test scores of the experimental and control groups is the effect of the intervention program connoting that the ACRIP is efficacious in reducing the symptoms of IGD (p=.001; F=529.14) and improving the psychological well-being (p=.001; F=592.69) of adolescents. Cohen’s d test measured the extent of the efficacy of the ACRIP after post-test in lowering the level of internet gaming disorder and increasing the psychological well-being of the experimental group. Resulting Cohen’s d value (IGD 7.27; PWB 7.23) shows the large effect of the ACRIP. The experiment which was also extended to selected Asian adolescents proved that ACRIP is efficacious and culture-free.

Conclusion/Recommendation

Given the resulting efficacy of ACRIP as an intervention program

that addresses the symptoms of IGD and the poor psychological

well-being of adolescents from various Asian cultures, this study

recommends that telemedicine adopt the ACRIP in addressing

IGD. The practice of telemedicine offers a new perspective in the

treatment of adolescents with gaming disorder in consideration

of patient well-being, preventing severe consequences in daily

life, and its mission to help ensure patients are provided with best

health care service available and in real-time whenever possible.

One of the IGD symptoms among the adolescents established

by APA was that these young people deceive family members,

therapists and others on the amount of their time spent gaming.

Telemedicine offers an enormous opportunity for these young

people to seek professional help without inhibitions and hesitations

mitigating the other symptoms of IGD and preventing them from

acquiring gaming addiction.

References

- https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/1448597234

- (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®), (5th edn). American Psychiatric Association, USA.

- Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD (2012) Internet gaming addiction: A systematic review of empirical research. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 10(2): 278-296.

- Stavropoulos V, Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD, Wilson P, Motti F (2017) MMORPG gaming and hostility predict internet addiction symptoms in adolescents: An empirical multilevel longitudinal study. Addictive Behaviors 64: 294-300.

- Kochuchakkalackal GK, Reyes MES (2019) An emerging mental health concern: Risk factors, symptoms, and impact of internet gaming disorder. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science 5: 70-78.

- (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM) (4th edn). American Psychiatric Association Washington, USA.

- Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD, Pontes HM (2017) Chaos and confusion in DSM-5 diagnosis of internet gaming disorder: Issues, concerns and recommendations for clarity in the field. J Behav Addict 6(2): 103-109.

- King D, Delfabbro PH (2014) The cognitive psychology of internet gaming disorder. Clin Psychol Rev 34(4): 298-308.

- King DL, Haagsma MC, Delfabbro PH, Gradisar M, Griffiths MD (2013) Towards a consensus definition of pathological video-gaming: A systematic review of psychometric assessment tools. Clin Psychol Rev 33(3): 331-342.

- Kochuchakkalackal GK, Reyes MES (2019) Development and efficacy of acceptance and cognitive restructuring intervention program on the symptoms of internet gaming disorder and psychological well-being of adolescents: A pilot study. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences 12(4): 141-145.

- Kochuchakkalackal GK, Reyes MES (2019) Efficacy of acceptance and cognitive restructuring intervention program on the symptoms of internet gaming disorder and psychological well-being of adolescents. Journal of Psychology and the Behavioral Sciences 5(2): 63-77.

- Davis RA (2001) A cognitive behavior model of pathological internet use. Computers in Human Behavior 17(2): 187-195.

- Langer EJ (2000) Mindful learning. Current Directions in Psychological Sciences 9(6): 220-223.

- Pontes HM, Griffiths MD (2015) Measuring DSM-5 internet gaming disorder: Development and validation of a short psychometric scale. Computers in Human Behavior 45: 137-143.

- Ryff CD, Keyes CLM (1995) The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 69(4): 719-727.

© 2020 Georgekutty Kochuchakkalackal Kuriala. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)