- Submissions

Full Text

Trends in Telemedicine & E-health

Mucosal Lymphoid Proliferation-Extra Nodal Marginal Zone Lymphoma

Anubha Bajaji*

Histopathologist in AB Diagnostics, India

*Corresponding author:Anubha Bajaji, Histopathologist in AB Diagnostics, India

Submission: January 29, 2019Published: March 13, 2019

ISSN: 2689-2707 Volume 1 Issue 3

Introduction

A common category of extra-nodal marginal zone lymphoma is cogitated by malignant transformation of the mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT). MALT lymphomas enunciate an estimated 70% instances of marginal zone lymphoma per annum and nearly 5% of non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Extra-nodal locations such as gastric and pulmonary tissue, breast, small intestine, salivary gland, thyroid and ocular adnexa are implicated. MALT lymphoma is further categorized into

a) gastric lymphoma, frequently involving a site such as the stomach and

b) non-gastric lymphoma devoid of an incrimination of the stomach, though adjunctive sites of the intestinal tract may be incriminated [1,2].

Disease characteristics

Mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas appear in regions which normally lack the presence of lymphoid tissue. Brief durations of chronic inflammation evoke the accumulation of B lymphocytes, followed by emergence of the lymphoma. Median age of disease representation is around 60 years. A slight female preponderance is elucidated. The world health organization (WHO) categorizes the mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma as an extra-nodal tumour and a histological delineation of heterogeneous marginal zone B lymphocytes displaying diverse centrocytoid, monocytoid or lymphocytoid morphology [2]. An admixture of scattered immunoblasts and centroblasts is enunciated. MALT being an indolent lymphoma, demonstrates a superior prognosis with a 5-year overall survival (OS) of 85%. An estimated one third (34%) instances of MALT lymphoma are cogitated as gastric tumefaction although the salivary glands, ocular adnexa, thyroid, breast, pulmonary and adjunctive tissues can be implicated [1,2].

Clinical elucidation

Clinical signs and symptoms of extra-nodal marginal zone lymphoma vary according to the site of primary neoplasm. Gastric MALT lymphomas are accompanied by systemic symptoms such as nonspecific dyspepsia, nausea, epigastric pain and gastro-intestinal bleeding. Emergence of MALT lymphoma is preceded by chronic infection, inflammation or an autoimmune disorder involving the implicated organ. Mucosal infection with Helicobacter pylori bacterium cogitates a chronic gastric irritability in concordance with the gastric MALT lymphoma. MALT lymphomas, particularly gastric tumours necessitate appropriate evaluation of disease with an optimal staging system. Although the staging system was originally designated for nodal marginal zone lymphomas, Ann Arbor classification can be adopted. However, it lacks appropriate and characteristic application to extra nodal marginal zone B cell lymphomas or gastric MALT lymphomas [3,4]. Thus, the modified Ann Arbor staging system as adapted for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma can be cogent. As the lymphoma disseminates to multitudinous extra-nodal locations, it is crucial to discern specific manifestations of occult lymphoma. Tumours devoid of confinement, to the gastro intestinal tract, enunciate an advanced, disseminated stage of MALT lymphoma on initial presentation.

Frequently, extra-nodal disease is a condition restricted to the site of origin, recapitulating Ann Arbor stage I E. It is associated with an infrequent incrimination of peripheral lymph nodes and bone marrow. Gastric MALT lymphoma along with one third instances of extra-nodal marginal zone lymphoma, is a frequent subtype delineating an early stage and localized disease. Disseminated lymphoma can be frequently elucidated in subjects where the primary disease is confined to non-gastric sites [4,5].

Disease pathogenesis

A perpetual proliferation of B lymphocytes with a persistent activation of the BCR signaling pathway is enunciated on account of a chronic inflammation secondary to an infectious or autoimmune aetiology. As an infectious aetiology in the pathogenesis of gastric MALT lymphoma is cogent. persistence of a chronic infection or inflammation engenders the emergence of a MALT lymphoma [1]. Infection with Helicobacter pylori appears to be a major causative aspect for the genesis of gastric MALT lymphoma. Helicobacter pylori infection activates the B lymphocytes, thereby initiating the lymphocytic conversion into a lymphoma. Similarly, orbital MALT lymphoma arises in concurrence with intercellular bacterium Chlamydia psittaci. Marginal zone lymphoma also emerges with concomitant infections of micro-organisms such as Borrelia burgdorferi (MALT lymphoma of the skin), Campylobacter jejuni (MALT lymphoma of the small intestine) and Achromobacter xylosoxidans (pulmonary MALT lymphoma). Viral infection such as a chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) can be implicated in the pathogenesis of non-gastric marginal zone lymphoma, chiefly the salivary or lacrimal gland lymphoma. Autoimmune disease augments the probable evolution of non-gastric MALT lymphomas. Disorders such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Sjogren’s syndrome associated immune sialadenitis typically elucidate a B lymphocyte infiltration confined to the thyroid or salivary glands respectively with subsequent malignant and progressive lymphoid proliferation [4,5]. However, infection with Helicobacter pylori, Chlamydia psittaci or the concurrent autoimmune disorders do not consistently evolve into a malignant lymphoma. Thus, adjunctive factors can be considered crucial and contingent to probable tumour emergence. Solid organ transplant recipients delineate an enhanced possible emergence of specific lymphomas such as the MALT marginal zone lymphoma. Therefore, immune suppression proves to be an aetiological attribute for the initiation of various subcategories of extra-nodal marginal zone B cell lymphoma [5].

Morphological elucidation

A histological confirmation of diagnosis is necessitated in order to prevent institution of excessive treatment of the benign reactive conditions or adjunctive lymphomas. MALT lymphomas can be adequately discerned with histological features as described in gastric biopsies in concurrence with immune histochemical evaluation. The cellular constituents of marginal zone B cell lymphoma transform into monocytoid B cells or mature plasma cells with a tissue specific homing pattern [3]. A population of miniature lymphocytic cells or monocytoid B cells with irregular nuclei constituting centrocyte like cells or plasmacytoid cells with mature plasma cells constitute the cellular component of MALT lymphoma. Occasional enlarged lymphoid cells can be demonstrated. Extra-nodal sites contingent to lining mucosa or glandular epithelia such as the gastrointestinal tract, salivary and lacrimal glands, lung, thyroid, conjunctiva, bladder and skin may be implicated by the tumefaction. The indolent lymphoma remains localized for an extended duration with predilection to reoccur in the epithelium of the extra nodal sites. Pseudo-lymphoma of the lung, stomach, skin and associated locations may recapitulate the tendency of epithelial recurrence [3]. Autoimmune disorders such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Sjogren’s syndrome may coexist.

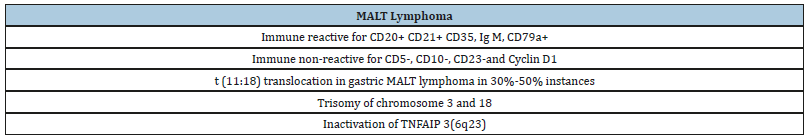

Immune phenotype

A characteristic immune reactivity for CD20+, and CD79a+ with non-reactive CD5-, CD10- and CD23- is elucidated. MALT lymphomas manifest an immune reactive CD21+ and CD35+ [1,3]. However, a categorical immune marker for recognizing MALT lymphomas is lacking. Cohesive zones of transformed and enlarged B lymphocytes indicate the emergence of a diffuse lymphoma (DLBCL). An enhanced cellular proliferation rate is quantified by assessing a Ki 67 (MIB 1) immune reactivity. The appearance of Helicobacter pylori is crucial in the detection of a gastric MALT lymphoma as bacterial elucidation influences subsequent therapeutic options. Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative bacterium and can be cogitated as an infectious and inflammatory agent lodged in the gastric mucosa and associated segments of the gastrointestinal tract. Helicobacter pylori can be discerned with innumerable investigations such as serology, urea breath test, faecal antigen test, histological elucidation and culture and sensitivity of the tissue specimens [1]. The assays are not standardized and devoid of appropriate recommendations and guidelines for selection of the investigations. An absence of Helicobacter pylori on histology is confirmed with several investigations such as the urea breath test, the stool antigen or serological tests (Figure 1-3).

Cytogenetic and molecular attributes

Gastric MALT lymphoma is a B lymphocyte lymphoma with an immunoglobulin light chain restriction. Clone specific genetic rearrangement of the immunoglobulin genes are exemplified. Variable region of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene is hyper-mutated. A post germinal center stage of differentiation is demonstrated; hence the post germinal B cell lymphoma elucidates a classic immune reactivity (CD10-, MUM1+ and BCL6+/-) [1,3]. Genomic rearrangements of CCND1, BCL2 and BCL6 genes are absent. Chromosomal translocation of t(11:18)(q21:q21), t(14:18) (q32:q21), t(1:14), (p22;q32) and t(3;14) (q14;q32) with the implication of API2-MALT1, IGH-MALT1, BCL10-IGH and FOXP1- IGH fusion genes are elucidated. The aforementioned genetic aberrations are considered exclusive for marginal zone lymphoma. API2-MALT1 translocation occurs in the gastrointestinal tract and lung, the IGH-MALT1 fusions genes are enunciated in the salivary gland, ocular adnexa or skin and the FOXP1- IGH genetic fusion is cogitated in the thyroid and ocular adnexa. Genomic rearrangements of the BCL10-IGH are exceptional. The technique of fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) or reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) can discern the chromosomal translocations, which are cogitated in an estimated one third (30%) of the instances and aid the classification of extra-nodal marginal zone lymphoma. Specific chromosomal translocations (API2-MALT1, IGH-MALT1 and FOXP1- IGH) produce a constitutive activation of the NF₭B signalling pathway which mobilizes genes such as cytokines and growth factors crucial for cellular activation, proliferation and survival. Trisomy 3 and 18 frequently concur in lymphomas of the intestine and salivary glands. Loss of function of the A20 molecule, a negative regulator of NF₭B pathway, is exhibited in restricted instances on account of chromosomal mutation, deletion and promoter methylation. Chromosomal translocation t(11:18) q21:q21 is encountered in gastric MALT lymphoma. The translocation promotes a genetic fusion between the BIRC3(API2)- MALT1 genes with the generation of a chimeric protein which augments cellular proliferation and survival by inhibiting apoptosis with concomitant activation of the NF₭B (nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells) signalling pathway. An estimated one third to half (30%-50%) of individuals with gastric MALT lymphoma delineating the genomic translocation enunciate a widely disseminated disease with a lack of infection with Helicobacter pylori [3]. A frequent, aberrant recombination elucidated in the non-gastric MALT lymphoma is the t (14:18)(q32:q21), amalgamating the IGH locus situated on chromosome14 and MALT1 locus located on chromosome18 . Trisomy of chromosome 3 and 18 is discerned along with the genomic inactivation of TNFAIP3(6q23). FOXP1 protein, appearing on account of chromosomal translocations or copy number changes, are elevated and indicate an inferior outcome in MALT lymphomas [3] (Figure 4-6).

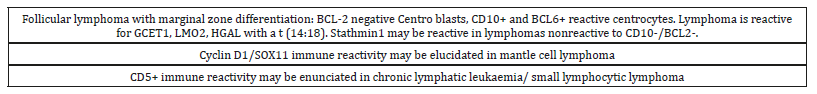

Investigative assay

A comprehensive radiological assay and adjunctive evaluation is necessitated on account of disease dissemination in MALT lymphomas, irrespective of the location of initial representation [5,6]. Disease discernment with the employment of fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) or computerized tomography (PET /CT) elucidates that the MALT lymphomas appear to be a fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose (F-FDG) avid tumour, particularly with the extra gastric manifestations. A pooled detection rate of 75% and a confidence interval of 95% can be cogitated with the aforementioned assay [6,7]. Thus, a fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET/CT) can be employed for preliminary investigations, especially in subjects where singular radiotherapy is adopted to manage localized disease. Diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a superior investigation as compared to computerized tomography (CT) and fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) scans for a pre-therapeutic assessment, staging and classification of MALT lymphomas [1]. European society of medical oncology (ESMO) guidelines recommends a conventional endoscopy of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum with multiple regional biopsies and histological evaluation of aberrant disease representations. An endoscopic ultrasound is employed for assessing the enlarged lymph nodes and thickness of the infiltrated gastric wall [6,7] (Figure 7-9).

Therapeutic options

The front-line treatment of patients with MALT lymphomas currently lack established guidelines for the institution of optimal therapeutic regimen. European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines corroborate the elimination of Helicobacter pylori microorganism from the gut mucosa, irrespective of the stage of gastric MALT lymphoma [7,8]. The appearance of translocation t(11:18) in gastric MALT lymphoma indicates an absence of therapeutic response to the elimination of Helicobacter pylori bacterium. Employment of antibiotic therapy for nongastric MALT lymphomas is debatable, except MALT lymphoma of the ocular adnexa where tetracycline induced decimation of Chlamydia psittaci enhances therapeutic response and progression free survival. Gastric MALT lymphoma benefits with appended antibiotic therapy applied to instances lacking the Helicobacter pylori infection although adjunctive species of the bacterium are cogitated such as Helicobacter heilmannii or Helicobacter fails [8,9]. Extensive therapy beyond the elimination of Helicobacter pylori or in individuals with non-gastric MALT lymphoma remains controversial. Subjects unresponsive to bacterial eradication of Helicobacter pylori, preliminary instances of gastric MALT lymphoma or non-gastric MALT lymphomas can benefit from localized radiation therapy. A moderate dosage of involved-field radiation therapy (24Gy-30Gy) administered over a 3-4 week duration achieves acceptable disease control. A minimal dosage of radiation therapy betwixt 2-4 Gy is efficacious for MALT lymphomas and is well tolerated with minimal toxicities. Minimal morbidity accompanying the radiation therapy is mandated in tissues such as ocular adnexa [9,10] (Figure 10-11).

Immunotherapy can be combined with chemotherapy or singular chemotherapy is efficaciously administered in MALT lymphoma, regardless of the stage. Administration of rituximab in concurrence with alternative chemotherapeutic agents such as chlorambucil elucidate superior outcomes, in contrast to application of a singular agent, although the overall survival (OS) is identical. Any site and any stage of MALT lymphoma can be managed by a combination of bendamustine and rituximab with favorable prognostic outcomes [10,11]. The 2 year and 4-year event free survival (EFS) is enunciated at 93% and 88% respectively. ESMO guidelines recommend a combination of rituximab with adjunctive chemotherapeutic agents for managing the systemic disease, although the combinative agents remain unspecified. MALT lymphoma appears concomitant to an infection with Helicobacter pylori. Thus, institution of the preliminary, triple therapy recommends the application of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) along with the administration of antibiotics such as clarithromycin, amoxicillin or metronidazole for a characteristic duration of two weeks. PPIs decrease the gastric acid production and prevent or assist the alleviation of gastric ulcers. Majority (90%) of instances recover following the institution of antibiotics and PPI therapy, though recovery is slow and extends over several months. Gastric MALT lymphomas can be low grade, minimally aggressive lesions with a gradual evolution and a lack of tumour dissemination [12,13]. Relapsing or refractory gastric MALT lymphoma, unresponsive to triple therapy are managed by additional therapeutic options such as radiotherapy, surgical excision or antibody conjugates such as rituximab or ibrutinib. Adults with marginal zone lymphoma can be administered ibrutinib as a component of systemic therapy, especially instances previously managed with a solitary/additional cycle of anti CD20 therapy [14]. Non-gastric MALT lymphomas localize in diverse sites and body tissues. Thus, the therapeutic intervention is cogent to the precise location of the tumefaction and proportionate dissemination. The treatment can be deferred till the discernment of constitutional symptoms, thereby constituting an approach of “active surveillance” (watchful waiting, careful observation). Monitoring of healthy or sick individuals can be approached with a systematic history/physical examination besides applicable investigative procedures such as laboratory and radiographic assay. The genesis of constitutional symptoms secondary to the lymphoma or investigative (laboratory/ radiographic/follow up) indications of disease progression mandate the institution of active therapy. Treatment comprises of surgical excision and radiation therapy. Immune therapy such as monoclonal antibody conjugate rituximab can be employed singularly or in combination with chemotherapy for managing advanced or progressive disease [13,15]. Bendamustine and rituximab are frequently employed for preliminary administration. Rituximab with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednionse (R CHOP) alleviates indolent tumefaction such as follicular lymphoma and can prove to be beneficial in treating extra-nodal marginal zone lymphoma. Doxycycline as an antibiotic is efficacious in marginal zone lymphoma incriminating the ocular adnexa. Termed as ocular adnexa lymphoma (OAL), coexistent infection with Chlamydia psittaci can be incriminated in the genesis of OAL [1].

Systemic reoccurrences are competently managed by ibrutinib. Institution of anti-retroviral therapy is recommended for marginal zone lymphoma accompanied by hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection as it impacts the transformation of malignant lymphoma. An estimated three fourths (75%) individuals with gastric MALT lymphoma infected with Helicobacter pylori can enter remission with appropriate antibiotic therapy as eradication of the microorganism is beneficial. However, an estimated half (50%) subjects with gastric MALT lymphoma infected with Helicobacter pylori relapse or depict a progressive disease when managed with singular antibiotic therapy and necessitate additional measures. A percentage of gastric MALT lymphomas uninfected by the Helicobacter pylori and individuals with non-gastric extra-nodal marginal zone lymphoma who may or may not elucidate a specific causative microbial agent can singularly benefit with the administration of antibiotics [13,15]. Thus, employment of singular antibiotic regimen can be attempted as a first line modality in a majority of subjects. Nevertheless, alternative and subsequent therapy is a pre-requisite in the majority. Optimal or second line treatment lacks appropriate consensus guidelines following preliminary therapeutic failure. Involved field radio-therapy (IFRT) with the optimal dosage of 25-35Gy is adopted in instances of gastric MALT lymphoma lacking a Helicobacter pylori infection. Individuals with a failure of Helicobacter pylori eradication or localized disease can adopt IFRT as a second line therapy with excellent control of localized disease [1]. However, disseminated disease is not adequately curtailed with IFRT. Rituximab can be alternatively employed in subjects of disseminated gastric or non-gastric lymphoma, ineligible for IFRT. Careful observation is appropriate as an initial approach. Institution of systemic therapy employs diverse combinations. Extra-nodal marginal zone lymphoma with a lack of preceding therapy can be managed with R CHOP (minimal adverse events) or bendamustine with rituximab (superior progression free survival). Bendamustine-rituximab combination is efficacious with minimal toxicities [13,15]. International Extra-nodal Lymphoma Study Group 19 (IELSG-19) trials recommend a singular therapy with chlorambucil or rituximab or a combination of the two displaying an identical overall survival. The drug combination provides a superior event free and progression free survival (EFS and PFS) and thus is considered an optimal initial therapy [1].

Relapsed and refractory

Extra-nodal marginal zone lymphoma necessitates a therapy simulating the regimes of advanced or disseminated disease and lacks cogent definition. In the absence of preceding therapy, rituximab combined with adjunctive chemotherapeutic agents are employed with an overall response rate (ORR) of 85%- 93%, a complete response (CR) of 54%-78% and grade III or IV hematological toxicity. Solitary rituximab or combined rituximab and chlorambucil can be instituted as an initial option. Bendamustine with rituximab is a favourable combination with an objective response rate of (ORR) of 93% and a complete remission (CR) of 71% in relapsed or refractory extra-nodal marginal zone lymphoma. Grade III or IV hematological toxicity can co-exist. Proteasome inhibitor bortezomib as a solitary agent depicts an objective response rate (ORR) of 48% and a complete remission (CR) of 31% in relapsed or refractory extra-nodal marginal zone lymphoma. Bortezomib can be combined with rituximab with an objective response rate (ORR) of 80% and a complete remission (CR) of 54% in relapsed or refractory extra-nodal marginal zone lymphoma. Rituximab in concurrence with immune modulating agent lenalidomide can be employed with an absence of toxicities [1] (Table 1-2).

Table 1:Immune phenotypic and cytogenetic attributes of marginal zone B cell lymphoma [1].

Table 2:Differential diagnosis of MALT marginal zone lymphoma [1].

Follow up

Table 3:Evaluation of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas [1].

Table 4:Follow up and monitoring of MALT marginal zone lymphoma (non-gastric and gastric) [1].

Non-gastric MALT lymphoma is monitored along the same lines as the indolent lymphomas. Gastric MALT lymphomas infected with Helicobacter pylori lacks a confirmatory eradication of the bacterium in the preceding six-week duration of antibiotic therapy. A gastric endoscopy with multiple tissue specimens for histological evaluation at 3-6 months following cessation of antibacterial therapy indicates the presence of residual bacteria. Histological evaluation of repetitive biopsies configures an essential component of disease follow up. Adequate interpretation of gastric lymphoid infiltrates subsequent to therapy prove to be difficult and complex. According to ESMO guidelines, a contemporary tissue assessment mandates a comparison and correlation with a pre-existing histological evaluation as per the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte (GELA) scoring system. An endoscopic evaluation with histological concordance is concluded at a six-month frequency over a 2-year period following treatment is recommended in order to assess a consistently regressing MALT lymphoma [1]. Temporary, localized reoccurrences of gastric MALT lymphoma lacking a Helicobacter pylori re-infection discerned upon histological assay are self-limiting. Gastric MALT lymphomas mandate a repetitive clinical and endoscopic assessment every twelve to eighteen months, as per the ESMO recommendations. Subjects with a gastric MALT lymphoma demonstrate a six-fold probable occurrence of a gastric adenocarcinoma, in contrast to the normal population [1] (Table 3-4).

References

- Cogliatti S, Bargetzi M (2016) Diagnosis and treatment of marginal zone lymphoma. Swiss Medical Weekly 146(Suppl 216).

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, et al. (2016) The 2016 revision of world health organization classification of lymphoid neoplasm. Blood 127(20): 2375-2390.

- John G, Laura L, Jesse K, Jeffrey M (2017) Rosai and Ackerman ‘s Surgical Pathology (11th edn), p: 1833.

- Bracci PM, Benavente Y, Turner JJ, Paltiel O, Slager SL, et al. (2014) Medical history, lifestyle, family history and occupational risk factors for marginal zone lymphoma: the inter lymph non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma subtypes project. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2014(48): 52-65.

- Olszewski AJ, Castillo JJ (2013) Survival of patients with marginal zone lymphoma: analysis of surveillance, epidemiology and end result database. Cancer 119(3): 629-638.

- Zucca E, Bertoni (2014) Emerging role of infectious aetiologies in the pathogenesis of marginal zone lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res 20(20): 5207-5216.

- Gill H, Chim CS, Au WY, Loong F, Tse E, et al. (2011) Non-gastric marginal zone B cell lymphoma: clinicopathologic features and treatment results. Ann Haematol 90(12): 1399-1407.

- Zucca E, Copie BC, Ricardi U, Thieblemont C, Raderer M, et al. (2013) Gastric marginal zone lymphoma of the MALT type: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow up. Ann Oncol 24 (Suppl 6): vi144-vi148.

- Kiesewetter B, Raderer M (2013) Antibiotic therapy in nongastrointestinal MALT lymphoma: a review of the literature. Blood 122(8): 1350-1357.

- Zucca E, Stathis A, Bertoni F (2014) The management of non-gastric MALT lymphomas. Oncology (Williston Park) 28(1): 86-93.

- Treglia G, Zucca E, Sadeghi R, Cavalli F, Giovanella L, et al. (2014) Detection rate of fluorine 18 fluoro-deoxy glucose positron emission tomography in patients with marginal zone lymphoma of the MALT type: a meta-analysis. Haematol Oncol 33(3): 113-124.

- Thieblemont C, Bertoni F, Copie-Bergman C, Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, et al. (2014) Chronic inflammation and extra-nodal marginal zone lymphoma of the MALT type. Semin Cancer Biol 24: 33-42.

- Park BB, Koo JS (2014) Helicobacter pylori infection in gastric mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol 20(11): 2751-2759.

- Denlinger NM, Epperla N (2018) Management of relapsed and refractory marginal zone lymphoma: focus on Ibrutinib. Cancer Management and Research 10: 615-624.

- Nishishinya MB, Pereda CA, Muñoz FS, Pego RJM, Rúa FI, et al. (2015) Identification of lymphoma predictors in primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int 35(1): 17-26.

© 2019 Anubha Bajaji. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)