- Submissions

Full Text

Trends in Textile Engineering & Fashion Technology

To Study on Famous Ancient Traditional Indian Costumes & Textiles

Ramratan Guru1*, Ushma Saini2 and Jyoti Rani3

1Assistant Professor Level III, School of Design, Mody University of Science and Technology, Rajasthan, India

2Assistant Professor, School of Design, Mody University of Science and Technology, Rajasthan, India

3Research Scholar, School of Design, Mody University of Science and Technology, Rajasthan, India

*Corresponding author:Ramratan Guru, Assistant Professor Level III, School of Design, Mody University of Science and Technology, Lakshmangarh- 332311, Rajasthan, India

Submission: February 15, 2023; Published: April 04, 2023

ISSN 2578-0271 Volume 8 Issue3

Abstract

Costumes and textiles have occupied a prominent place in the world, across geographic regions and climatic conditions, since ancient times. People naturally utilized whatever material was conveniently available. Over time, the designing of textiles and costumes developed in the hands of artisans as they enriched fabric and garments. In fact, contemporary textiles and costumes reflect our spirit, our consciousness, and the vibrancy of the society in which we live. This is how textile and costume designing has evolved in India. Artisans and craftsmen have played a pivotal role in textile designing since prehistoric times. The vision vocabulary of the artisan and functional usage of art facts have led to important contributions in the development of artistic designs. However, the distinction of techniques was not distinct, and frequently one technique may merge into another, resulting in differences in defining shapes and styles. These patterns represent the gradual blending of indigenous artistic abilities, contemporary cultural influences, and sign and symbol imagery. In this review study we have shared Indian traditional costumes & textile knowledge. So that wills every person easily understanding the ancient Indian traditional costumes & textile knowledge.

Keywords:Traditional Indian costumes; Different civilizations periods in textile & dyes

Introduction

Costumes and Textiles have involved a conspicuous spot on the planet, across geographic districts and climatic circumstances, since old times. Individuals normally used anything that material was helpfully accessible. After some time, the planning of Textiles and ensembles was created in the possession of craftsman’s as they enhanced texture and articles of clothing. Truth be told, contemporary Textiles and ensembles mirror our soul, our cognizance, and the dynamic quality of the general public in which we live [1-3].

History affirms that man has all along been designing and making for his own satisfaction. It is, along these lines that his fundamental love of nature has been manifested straight forwardly or in a roundabout way in every single such creation. The improvement of customary Indian materials and outfits for more than a few thousand years is the nation’s geology. In the social and verifiable sense, India is a tremendous subcontinent of clearly differentiating actual elements and relating varieties in the environment. These varieties gave rise to a multitude of art forms, languages and dialects, religions and spiritual traditions, customary societies, and so on. These various expressions of culture were complemented by the natural resources of India, such as its abundant flora and fauna, its changing climate, and its highly varied geography [4-5].

Indus Valley Civilization

Indus Valley Civilization, also known as Bronze Age civilization, that existed in parts of present-day Pakistan, northwest India, and northeast Afghanistan between 3300 and 1300 BCE. There may have been more than 5 million people living throughout the Indus Civilization.This Bronze Age civilization was contemporaneous with ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, and it was noted for its urban planning, efficient drainage systems, and large-scale production of cotton textiles. The cities are renowned for their masterful urban planning, baked-brick homes, intricate water supply and drainage systems, and groups of sizable non-residential structures. As a result of Harappa, the first of its sites to be discovered during excavations in the 1920s in what was then the Punjab province of British India [6].

Costumes

In the Indus Valley Civilization, there are some depictions of men sporting turbans. These turbans are not just fashion statements; they are an integral part of their culture and represent the power that comes with it. Women appeared to have worn knee-length skirts in the Indus Valley Civilization. The women utilised various cosmetic products for make-up, such as kohl, red lipstick, and nail polish. As a symbol of their high social status, the women and men of the Indus Valley Civilization would often adorn themselves with jewellery made of gold and silver, and wear garments adorned with precious stones. Figurines and grave artefacts demonstrate that both sexes of the Harappans wore jewellery: men wore hair fillets, bead necklaces, and bangles; women wore bangles, earrings, rings, anklets, chokers, pendants, and a variety of necklaces, along with ornate hairstyles and headdresses. Women wore a lot of bangles, including wide ones below the elbow and hefty ones above. They were fashioned of terracotta for everyday use. The more intricate or painstakingly crafted a piece of jewellery was, the higher its price. Gold and silver were valued equally.

Varied styles of folding and draping lengths of material served as the basis for clothing. Such a fabric might have been created from linen, cotton, wool, or animal hair. In frigid climates, skins may have also been used to produce belts, quivers, and other accessories. Although it is unknown how frequently shoes may have been worn, reeds or straw may have been made for them.

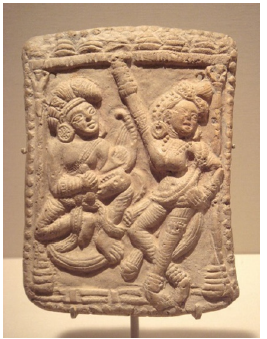

Men and women are shown wearing a variety of stitched clothes, like tunics, cloaks, basic skirts, and pants, as well as unstitched fabric draped around their bodies (Figure 1a). The statue of a man whose identity is widely assumed to be a priest, though he may actually be a nobleman or perhaps a divinity, was found as one of the statues at Mahenjodaro. His thoughtful look, as well as the formal drape of his patterned robe or shawl, which must have developed from a specific sartorial tradition, all contribute to his regal demeanour (Figure 1b), a sculpture of a lithe and graceful dancing girl, was found in the same region and is surprisingly lifelike. She is unclothed and has a calm posture, although her arms and neck are richly adorned with jewellery. Figure 2 shows the different draping styles of people [7,8]..

Figure 1:(a) Statues of priest-king draped in patterned robe or shawl (b) Bronze statuette of a dancing girl.

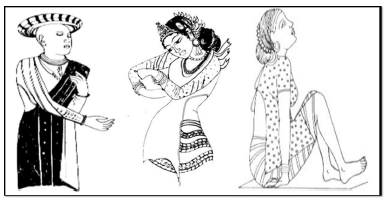

Figure 2:Childerns and womens garment drapping style.

Textiles

There is not much textile evidence from the Harappan period, and figurines are typically found without clothing. The Harappans has woven a variety of cotton cloth grades, as evidenced by the small bits of cloth that have survived in the corrosion products of metal items. There was flax cultivation and potential fibre use. It is possible that native Indian silkworm species were used to produce silk. Although it is unknown if the Harappans kept woolly sheep, their trade with Mesopotamia most likely provided them with a plentiful supply of Mesopotamian woollen fabrics. Additionally, it is likely that the Harappans carried on the past practice of producing leather clothes. The few depictions of attire reveal that men often wore a dhoti-like material around their waists that was commonly passed between their legs and tucked up behind them [9].

Vedic Era

During the Vedic period (1500–500 BCE) in Indian history, the Vedas were written. These are the oldest Hindu texts. This period saw a reinterpretation and integration of the various ancient Indian traditions, with the Upanishads being particularly influential. During this period, Vedic practices were codified and transmitted in the form of written works, such as the Brahmanas and Sutras. They are considered to be divine revelations and contain a large variety of philosophical, religious, and ritualistic teachings. The Indo-Aryans arrived in northern India at the beginning of the Vedic period, bringing with them their unique religious practices. Large, urbanized states and shramana groups, such as Jainism and Buddhism, which questioned Vedic authority, began to emerge at the end of the Vedic period. The Vedic tradition was a key component in the so-called “Hindu synthesis” at the beginning of the Common Era [10,11].

Costumes

During the Vedic age, most clothing consisted of a single piece of cloth slung over one shoulder and wrapped around the entire body. People wore “paridhana”, an undergarment with pleats in the front called “mekhla”, and an upper garment called “uttriya”. Uttariya is usually thrown over the left shoulder only by orthodox men and women; This style is known as Upavita. The simplest article of clothing for ladies was “the Sari,” as the Vedic people were only beginning to sew clothing. The sari, typically made from cotton or silk, was a long strip of fabric that draped around the body and could be used to create different types of garments. It is a long piece of fabric that should be draped over a woman’s body in a particular way. It is around six to nine yards long. Although the earliest draping methods were quite simple, they were gradually modified according to regional basis [12]. But the most typical way to wear a sari was to wrap one end around the waist and drape the other end over the shoulder to cover the bust area. A blouse, also known as a “Choli,” was added to the sari as an upper body garment with sleeves and a neck. The smaller form of the sari known as “the Duptta” is another item of Vedic attire that resembles it. It is only a few metres long and was frequently incorporated into elaborate outfits during the later Vedic era, including the “Ghagra Choli,” which consists of a long skirt worn with a blouse and a duptta [13].

During the Vedic age, men also wore long pieces of cloth wrapped around themselves. The most traditional clothing for Vedic men was called a “dhoti”, which is a scarf-like garment slightly longer than the dupatta. However, the men divide his waist with straps and hang the dhoti around it. Men only wore the dhoti, as they were not required to wear any of the upper garments during this time. The “lungi,” which simply wrapped around the man’s waist and was pleated in the middle but not split, was another similar item worn by men. However, as the Vedic people learned stitching techniques, they created the “kurta,” a loose upper-body garment resembling a shirt. Then came the “pyjamas,” which resembled a loose pair of pants. Men also wore headgear, such as a turban, which was draped in various regional fashions [14].

Mauryan and Sunga Period (321-72 BC)

From roughly 187 to 78 BCE, the ancient Indian Brahmin Shunga Empire, which originated in Magadha, ruled over substantial portions. The Shunga Empire was known for its advanced military technology and impressive infrastructure during this time period. At present time, the remains of their civilization can be found all over North India, with archaeological sites located in modern-day Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Odisha. Small terracotta artworks, huge stone sculptures, and architectural marvels like the stupa at Bharhut and the well-known Great Stupa at Sanchi all flourished during this time, as did philosophy, education, and other branches of learning. These advancements in art, culture, and architecture were so significant that they greatly contributed to the evolution of North Indian civilization [15,16] (Figure 3).

Figure 3:Vedic Era a man wear dhoti with loose shirt or other man wearing dhoti and take woolen Shawal (topper).

Costumes

The principal dress was the antariya, which was made of white cotton, linen, or floral muslin and occasionally embellished with valuable stones and gold thread. Antariya was wearing the kachcha style, which was a length of unstitched cloth that was worn by men between the legs and around the hips. It was held together at the waist by a sash called a kanchuki, and women often wore their antariyas along with a blouse, or anga. The kayabandh was tied at the front of the waist in the middle, in a loop, and served as the antariya’s waistband. The kayabandh might be a straightforward sash called a vethaka, a muraja with drum-headed knots at the ends, a pattika, a particularly ornate band of embroidery that is flat and ribbon-shaped, or a kalabuka with numerous strings. All of these styles served the same purpose, which was to secure the antariya around the body and provide some decorative embellishment. The third piece of clothing was known as the uttariya. The only change was how things were worn. Its one end is sometimes draped over both shoulders, while other times it is tossed over one shoulder. This material was frequently fine cotton and, on rare occasions, silk. The uttariya could be worn in a variety of ways to suit the wearer’s comfort. It would be fashioned of coarse cotton for the underprivileged members of society. One of the earliest examples of cut-and-sewn clothing is the tunic, which has a wide front opening with ties at the neck and waist and is hip-length. It has short sleeves and a round neck [17,18] (Figure 4,5).

Figure 4:Shunga period The Woman statue: evidence of stitching, Mathura, 3rd century BCE (Walters Art Museum, Wikipedia).

Figure 5:Sunga time period Royal Family garment style (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Wikimedia Commons).

Textiles & dyes

In the Shunga period, cloth was used; both fine and coarse kinds could be woven with ease. In this time period, most fabrics were made of cotton, silk, wool, linen, and jute because they were widely accessible. The best kinds of fur, wool, and silk were used to make luxurious fabrics for the wealthier members of society. Some of the examples of silks used were tussar, which is bleached to become patrona and has a yellowish natural tint like Eri or Muga silk from Assam. The vivid crimson woolen blankets of Gandhara and Kaseyyaka (high quality cotton or silk) were each worth a small fortune. Nepal had woolen textiles that could withstand rain. Greek travelers to Chandragupta Maurya’s court have spoken about resist dyeing and hand-printing designs on fabric, as well as the Indian glazed cotton cloth that was in widespread use by 400 BC. Long before the Mauryans, materials resembling khinkhwab, which is made by weaving silk and gold or silver wires into a lovely floral design, were in high demand and were sold to Babylon. The north had both coarse and fine forms of cotton, wool, and a fabric called karpasa. Additionally, there were delicate muslins known as “shabnam.” The edges of blankets or kambala were either finished with braids or borders, or woven wool strips were sewn together. Rajaka, the washer men, were also dyers, and after washing the clothes, they would perfume them. Red, white, yellow, and blue were recognised as the four primary colours used in textile dyeing (indigo leaves). For usage as carpets, bedcovers, blankets, and clothing, fabrics were additionally printed and pattern-woven.

Satavahana Period (Andhra)

The Satavahana Empire was an Indian dynasty with bases in Dharanikota, Amaravati, Junnar (Pune), and Prathisthan (Paithan), all of which are in Andhra Pradesh. From 230 BCE forward, the empire’s realm included much of present-day India. Although there is significant disagreement regarding the dynasty’s end date, the most optimistic estimates place its duration at almost 450 years, or until 220 CE. After the Mauryan Empire fell, the Satavahana are credited with bringing about peace in the nation by fending off the invasion of foreigners. When Ashoka died (232 BCE), the Mauryan Empire was starting to fall apart, and the Satavahana declared their independence. They honoured other manifestations of Gauri, Indra, the sun, and the moon in addition to Vishnu and Shiva. As one of the longest reigning dynasties in Indian history, the Satavahana dynasty reigned for several centuries and shaped much of ancient India [19].

Satavahana costume

Tunics and kancukas with stripes or beehive patterns were worn by servants or hunters in the first century BC during the Early Satavahana period. The sleeves of the kancuka can be short or long, and the opening can be on the left side or the front. Tunics and kancukas were mid-thigh in length. In hunting attire, the King’s tunic lacks a visible neck opening. There are variations in necklines, with some being round or V-shaped shaped. These tunics and kancukas were often designed with intricate details such as decorative embroidery and gold trim. The Dravidians’ indigenous village women also changed their attire [20]. They resembled the Lambadis, a modern-day Deccan gypsy clan, save for the skirt. The female attendant wore transparent long antariyas and lovely ornate tips in the royal court attire of the Mauryan-Sunga people. At home, the king and most of his courtiers wore short, informal native antariya. In contrast, the village women wore a nine-yard unstitched antariya and tied it around their waist in an intricate knot. The kayabandh can be worn looped in a semicircle at the front with noticeable side tassels, tied like a thick rope, or constructed of thick, twisted silk (Figure 6).

Figure 6:Sculpture of the Satavahana Royals.

In the later Satavahana period, both men’s and women’s uttariyas were typically white and made of cotton or silk. But occasionally, it had lovely hues and was embroidered. Men could throw it over both shoulders. Both sexes continued to wear the antariya in the kachcha style. In the king’s court, attendants, grooms, guards, and others frequently wore a sewn foreign garment known as the kancuka. The only way to see the drape in the early Andhra sculptures is through two double-incised lines. The vethaka was the kayabandh in the shape of a straightforward sash. The pattika, a garment comprised of flat ribbon-shaped segments of typically silk fabric, was also worn by the women.

The kancuka, a stitched foreign garment that looked like a skirt, was widely worn by numerous people. Women also wore the short kancuka in a variety of ways, such as pairing it with an ethnic antariya or, when it was calf-length, a kayabandh and an uttariya [21].

Textiles & dyes

Silk played a significant role in the wardrobes of the wealthy, and both coarse and fine forms of cotton were in high demand. The weavers and many types of labourers wore clothing made of hemp that was quite affordable. In the warm temperature of the Satavahana-ruled region of India, wool was not frequently required, but it was employed in the form of chaddarsor blankets during the winter. Since the Vedic era, a wide range of dyes have been used, including indigo, yellow, crimson, magenta, black, and turmeric. To expand their selection of coloured fabrics, the Satavahana must have also integrated hues and colour combinations that were familiar to those nations with which they engaged in extensive trade, such as China, Persia, and Rome. Textiles with printed and woven patterns were widely available, and among the wealthier classes, gold embroidery was especially popular. The uttariya, in example, was frequently made of silk and had floral embroidery all over it or featured a pattern with birds and flowers. Although these uttariyas were sometimes bordered with precious stones or painted blue or crimson, a pure white remained the preference of males.

Kushan Period (130 B.C - 185 A.D)

The Satavahana (Andhra) and western Satraps (Sakas) kingdoms existed at the same time as the Kushans throughout a portion of the second century AD. The Kushans were most prominent in the eastern and central parts of India, while the Satavahana and Satraps empires held sway in western and southern India, respectively. The Kushans founded their empire in the first century A.D. Envoys were used to establish communication with numerous regions of western Asia and the Mediterranean. This naturally aided international trade, and the arrival of outsiders like the Kushans, Sakas, and Indo-Greeks further boosted economic ties with these regions. Not only did this bring an influx of luxury items and goods from far-off lands, but it also opened up opportunities for knowledge exchange, inspiring the development of local art and culture [17,18].

Costumes

The Buddhists who were present were clothed in chitons, rimations, stolas, tunicas, chlamys, and other traditional Greek and Roman garb. The standard attire for men and women was a turban, an antariya, and an uttariya. There are five main categories of Kushan costumes: local people theantariya, uttariya, and kayabandh, guards and harem attendants (red-brown); stitched kancuka, alien Kushan rulers and their retinu; and other foreigners. The tight-fitting, calf-length tunic, which was occasionally made of leather, might be paired with a short cloak, a woolen coat or caftan that was worn loosely. Third attire, the chugha, was occasionally worn in addition to these two upper garments. The chugha has slits for easy mobility and was adorned with a border down the chest and hemline. In the summer, the trousers could be made of muslin, silk, or linen; in the winter, they were made of wool or were quilted. Thestanamsuka tunic has a basic round neckline, long sleeves, and a flared hem. It is form-fitting. Sometimes, antariya and uttariya in the lehnga style are worn. There are also occasional representations of ladies dressed in an uttariya, a long-sleeved jacket, and tightfitting ruched pants. The big shawl known as the pravara or chaddar, which was believed to have been perfumed with bakul, jasmine, and other perfumes, was still worn by both sexes to guard against the cold. With little alterations, the primary Indian clothing remained the purely native antariya, uttariys, and kayabandh [19]. The kayabandh, a broad, twisted sash used primarily by ladies in many wonderful ways to enhance the figure, evolved into a more loosely worn informal piece of clothing.

Textiles & dyes

Textiles made of tulapansi, light cotton, were popular in central India. There were many local and foreign skills available, but they were still highly expensive. When antariya were adorned, it seems that they were stitched, woven, or printed with diagonal check patterns surrounding tiny circles. Antariya were extremely infrequently embellished. Rich women’s turbans were frequently diagonally striped with pearls on every third line. Beds and chairs were also covered in the same gilded fabric. There were also many more geometric prints and weaves, including checks, stripes, and triangles. Hand-Knotted Carpets by Kush tints and shades of blue’s, earthy tone colors, and rich dark yellow-brown fabrics were among those discovered along the historic silk path [20] (Figure 7).

Figure 7:Kushan period costumes.

Gupta Period (Early 4th- Mid 8th A.D)

After a protracted period of upheaval that followed the demise of the Kushan empire in the middle of the third century AD. Only when the Gupta Empire was established was there nearly total peace and unity throughout North India. The Gupta empire was enormous and lasted for more than two centuries; it included a large portion of north India and extended to Balkh in the east. the development of an effective administrative structure as well as a level of harmony and balance in all the arts, The Gupta era, also called as the “Golden Age” and the “Classical Period,” Bengal is where the Guptas are most likely to have originated. The Guptas ruled a few minor Hindu kingdoms in Magadha and the area of present-day Uttar Pradesh at the start of the 4th century [21,22].

Costumes

During the Gupta era, cut-and-sewn clothing predominated. For affluent people, like nobles and courtiers, a long-sleeved brocaded tunic became the standard attire. Most frequently, a blue, tightly woven silk antariya with possibly a block printed pattern served as the king’s principal attire. A plain belt replaced the kayabandh in order to tighten the antariya. Ivory was extensively used during that time for jewellery and decorations. Only around this time did stitched clothing really start to gain popularity. Clothing with stitches began to represent royalty. However, antariya, uttariya, and other attire were still in use. The antariya that the women were wearing gradually changed into gagri, which has several whirling effects accentuated by its numerous folds. Numerous Ajanta paintings make it clear that back then, ladies only wore the lowest portion of their clothing, leaving the bust area naked. Later, many types of blouses (Cholis) emerged. Some of them were tied from the front, showing the midriff, while others had strings connected, leaving the back exposed. Calanika was an antariya that could be worn with both a kachcha and a lehnga.

Textiles & dyes

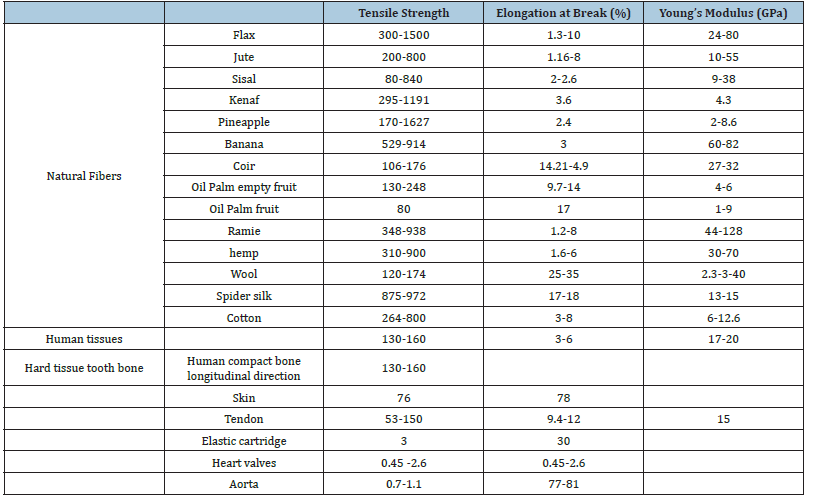

The finest fabrics, printed, painted, coloured, and highly patterned in weaving or needlework, were available during the Gupta era. Many of the conventional prints used today were created during this time, when the skill of calico printing significantly developed. There were stripes, checks, and animal and bird themes, including geese, swans, deer, elephants, and others. Hundreds of various species of flowers and birds were expertly embroidered on muslins, and beautifully woven brocades, which were still popular, were also masterfully made. While the art of needlework achieved its pinnacle of development in the north and north-west, gold and silver woven brocades of Benares were still in use. Particularly for pillows, black and white checkered silk was woven. These cushions had elegant covers made of gold, silver, or dark-colored linen that included silver stars, four-petaled flowers, or stripes with chesspatterned bands. Special floor carpets and rugs called rallaka and kambala, as well as bedcovers known as Nicola and pracchadapata, were created. The dying process was also quite sophisticated, and the typical diagonal stripes occasionally blended together as soft and dark tones. The resist dyeing method produced this lovely appearance. Pulakabandha, a type of tie-dying popular in Gujarat and Rajasthan, was employed extensively in women’s upper clothing and came in a wide variety of patterns. Rasimalis known that the expensive, special silk cloth known as stavaraka was imported into India from Persia. This garment was worn by royalty and was adorned with clusters of vivid pearls (Figure 8) (Table 1) [1,14,18,21].

Figure 8:Gupta period men’s and women’s costumes draping style.

Table 1:Different civilizations costumes, textile & dyes [1,14,18,21].

Conclusion

The individual’s curiosity has always included outfits from many eras. Traditional attire and costumes are items worn to express one’s nationality, culture, or religion. They serve as a time capsule and social commentary. Human nature has always been drawn to clothing and textiles because of their individuality and elegance. With time, the traditional attire began to disappear. Indian traditional clothing has roots in the country’s history and dates back a very long time. Indian apparel still has its own character and significance today, despite how the fashions have evolved over time and varied according to regional distinctions throughout India. There are many different types of traditional costumes in India, such as the sari (a single piece of draped clothing for women), the salwar kameez (a traditional outfit for women that consists of three pieces: the Punjabi kameez, salwar, and duptta), the kurta (a long shirt-like garment), the Lungi (men’s clothing) etc. It will more help for youth to easily understanding knowledge for cultural, ancient traditional Indian costumes & textiles. This all-ancient traditional costumes & textiles add on exist garments market, so that will be new creating garment special category in textile & apparel sectors. So that this will be more boost in textiles & apparel sectors like handloom, handicraft etc. It will more create employment in urban and rural area. So that will be continuous exist fashion market of ancient traditional Indian costumes & textiles in the around globe.

References

- Thakar Karun, Crill R, Fotheringham A, Cohen S (2021) Indian textiles 1000 Years of Art and Design. Indian Books and Periodicals.

- Zimmer H (1946) Myths & Symbolic in Indian art & civilization. New York, USA.

- (2014) Traditional Indian Textiles Class XII Students Handbook + Practical Manual. The Secretary, Central Board of Secondary Education, Shiksha Kendra, Community Centre, Preet Vihar, Delhi.

- Bhatnaga P (2009) Traditional Indian costumes and textiles. Publisher by Abhishek Publication, India.

- Bhandar B (2004) Costume, textiles & jewellery of India publisher by prakash books India Pvt. Ltd.-113A, Darya Ganj, New Delhi, India.

- Kenoyer JM (1991) Ornament Styles of The Indus Valley Tradition: Evidence from Recent Excavations at Harappa, Pakistan. Paléorient Journal 17(2): 79-98,

- Majumdar RC (1955) The history & culture of the Indian people, Bombay, India 7: 63-69.

- Biswas A (2017) Indian costumes. Publications Division, M/O Information& Broadcasting, Govt. of India,

- Ghurye GS (1995) Indian Costume. Popular Prakashan Pvt. Ltd.

- Biswas A (2007) Indian costumes. Publications Division Ministry of Information & Broadcasting.

- Alkazi R (1996) Ancient Indian Costume. National Book Trust.

- Pandey IP (1988) Dress and Ornaments in Ancient India. Bharatiya Vidya Prakashan, India.

- Longhurst AH (1938) The Buddhist antiquities of Nagarjunakonda, Madras Presidency. Archaeological Survey of India, Delhi, India.

- Sivaramamurri C (1942) Amaravati, sculptures in the Madras Museum, Bulletin of the Madras Govt. Museum N.S.G.S., general section, Madras, India.

- Bachhofer I (1929) Early Indian sculpture, New York, USA, Vol 2.

- Burgess J (1892) Ancient monuments, temples & sculpture of India, London, England.

- Alberr G (1901) Buddhist art in India, London, England.

- Fergusson J, Burgess J (1880) Cave temples of India, London, England.

- George R (1876) The seventh great oriental monarchy, London, England.

- Kumar R, Muscat C (1999) Costumes and textiles of royal India. Christies Wine Pubns.

- Burgess J (1900) Gandhara sculptures. Journal of Indian Art, London, England.

- Agrawala VS (1977) Gupta Art (A History of Indian Art in the Gupta Period 300-600 A.D.): Indian Art, Volume 2.

© 2023 Ramratan Guru. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)