- Submissions

Full Text

Techniques in Neurosurgery & Neurology

Complications of Surgery for Pituitary Adenomas-A Retrospective Review of Single Institutional Experience

Ugwuanyi CU1*, Anigbo AA1, Salawu MM2, Jibrin P3, Okpata CI1, Ayogu OM1, Igbokwe KK4, Mordi CO4, Onobun DE4 and Okafor IW4

1Neurosurgery unit National Hospital, Nigeria

2Neuroanasthesia unit National Hospital, Nigeria

3Neuropathology unit National Hospital, Nigeria

4Wellington neurosurgery Centre, Nigeria

*Corresponding author: Ugwuanyi CU, Neurosurgery Unit National Hospital, Nigeria

Submission: December 1, 2021;Published: January 21, 2022

ISSN 2637-7748

Volume4 Issue5

Abstract

Introduction: Considering the central endocrine regulating functions of the pituitary gland and its unique anatomical location underneath the hypothalamus, a sound knowledge of common complications of surgery on the pituitary gland propels a proactive management approach for a good outcome. Aims and Objectives: To review the commonly observed complications following surgery for pituitary adenomas

Methodology: A retrospective review of documentations on case notes of complications encountered following surgery for Pituitary Adenomas was conducted in 22 consecutive cases. Parameters of interest were biodata, clinical, biochemical and radiological diagnosis, surgical approach, complications and outcome. Complications of Interest were, Diabetes Insipidus, CSF Leak, Meningitis, Dyselectrolytemia, Hemorrhage Hormone Imbalance and Outcome. Data was assembled on excel spread sheet and analyzed with simple descriptive statistics and results presented in Tables & Figures.

Result: 14 males (63.6%) and 8 females (37.4%) M: F (1.75: 1). Age range was 31-74, mean 50.5 years, SD 11.8 years. Commonest indication for surgery was nonfunctional macro adenoma with mass effect (54.6%) followed by prolactin secreting macro adenoma (40.9%) and Apoplexy (5.5%). Surgical approach was trans-sphenoidal route in 18/22 (82%) and transcranial in 4/22 (18%). Diabetes insipidus was the commonest complication 13/22 (59.1%), followed by CSF leak in 5/22 (22.7%) which was complicated by meningitis in 3 of 5 cases. Other complications were dyselectrolytemia, intraventricular hemorrhage, hypopituitarism. Mortality was 18% due to meningitis in two cases, IVH/obstructive hydrocephalus and dyselectolytemia one case each.

Conclusion: Pituitary surgery is safe but does carry some risks of various postoperative complications which must be considered right from pre-op consent all through the execution of the operation and post op management in order to sustain the low morbidity and mortality usually associated with this operation.

Keywords: Pituitary adenoma; Pituitary surgery; Complications; Outcome

Introduction

Mediums are said to act as the “go-between” for “spirit communication” by deceased entities (discarnates) to other living beings [1] and are characterized by anomalous neurological patterns associated with trance and non-trance states that can be seen as a form of dissociation [2-4]. These trances can occur in varying degrees of wakefulness and are said to be abnormal states of consciousness where the medium is either unaware of external stimuli taking control of their body or is selectively responsive to receiving messages and information from discarnates [5-7]. Several factors indicate that mediumship as a non-ordinary state of consciousness does not reflect a need for pathological diagnoses, nor are natural occurrences for mediums inherently negative [5,8]. Studies presenting evidence of authentic mediumship demonstrate how these individuals experience distinct neurological correlates when communicating with discarnates, and that their information is largely sound, which makes this state different from mental disorders (MDs) [9]. Arguments supporting the integration of mediumistic abilities for individuals experiencing anomalous information reception (AIR) and transfer (AIT) point to a reduction of distress and deflection of pathological diagnoses [10-12].

Historical Prevalence

Tumors of the pituitary gland represent approximately 10% of diagnosed brain neoplasm, and often cause disabling visual and endocrine disturbances which impairs quality of life and the transsphenoidal resection of pituitary tumors presently account for as much as 20% of all intracranial operations performed for primary brain tumors [1]. Transcranial approach to pituitary tumors is presently limited to a few cases such as large suprasellar mass with poorly defined sella especially in “cottage loaf” tumor appearance, lateral extrasellar extension of tumor into the cavernous sinus and middle fossa, associated parasellar aneurysm, recurrent or residual fibrous tumor [2]. In the past few decades, there has been a sustained scientific revalidation of the trans nasal transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary tumors, which has now become the standard procedure for more than 90% of the sellar lesions [3]. This has derived a lot of inspiration from the previous works of Cushing’s, Dott, and Guiot [4-6] who remained faithful to the sublabial rhinoseptal midline approach and also the alternative lateral endonasal approach originally used by Hirsch but eventually revived by Griffith in 1987 [7]. In general, postoperative complications are of major concern in patient with intracranial lesion because it leads to a significant increase in morbidity and mortality [8]. Considering the central endocrine regulating functions of the pituitary gland and its unique anatomical location, various postoperative complications can be anticipated from surgery on pituitary tumors [9]. A proactive approach then becomes expedient in improving the outcome. The focus of this review is to share our experience regarding the complications of surgery for pituitary adenoma in our institution which will contribute to the quality of care provided to future generations of these patients. The aims and objectives of this study is to review the commonly observed complications following surgery for pituitary adenomas and associated mortality over a 3-year period at Neurosurgery unit of the Wellington Hospital Abuja Methodology-Following necessary ethical considerations and clearances obtained from the institutional review board, a retrospective review of documentations on case notes regarding complications encountered following surgery for Pituitary Adenomas was conducted on 22 consecutive cases over a three years period. Parameters of study interest were biodata, presentations (clinical, biochemical and radiological) surgical approach (transsphenoidal, transcranial) relevant complications and outcome. Complications of major interest were (Diabetes Insipidus, CSF Leak, Meningitis, Dyselectrolytemia, Hemorrhage). Data was assembled on excel spread sheet and analyzed with simple descriptive statistics and results presented.

Result

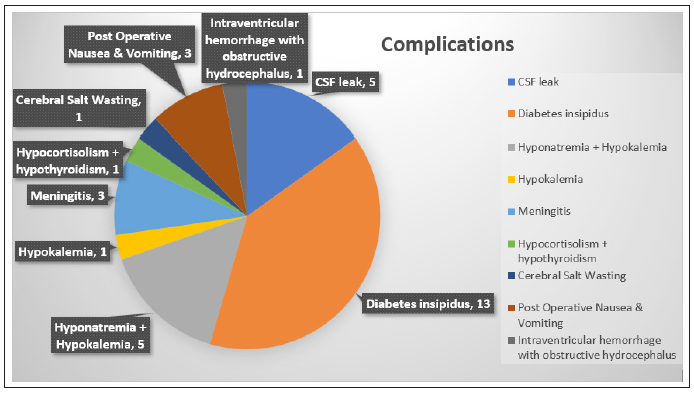

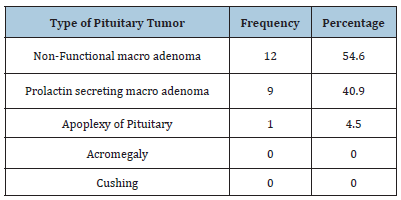

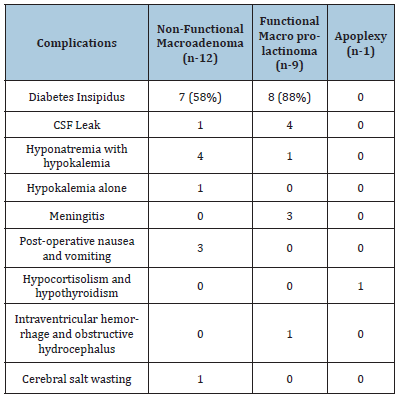

Following pre-op evaluations including neuroimaging and hormone profiling, it was found that the commonest diagnostic indication for surgery was nonfunctional macro adenoma with mass effect (54.6%) especially visual field defects followed by prolactin secreting macro adenoma (40.9%) and Apoplexy (5.5%). No cases of acromegaly and Cushings were recorded yet (Table 1). Surgical approach was trans-sphenoidal route in 18/22 (82%) and transcranial in 4/22 (18%). For the trans-sphenoidal route, trans nasal microscopic was 15/18(83.3%) and endoscopic 3/18 (16.6%). The overall recorded complications are detailed in Figure 1 and revealed that diabetes insipidus was the commonest as recorded in 13/22 (59.1%). The second and most significant complication was CSF leak in 5/22 (22.7%) which was complicated by meningitis in 3/5 cases. Post-operative nausea and vomiting was transiently observed on three cases. Of concern were dyselectrolytemia including SIADH (dilutional hyponatremia), cerebral salt wasting, and hypokalemia as displayed on Figure 1. Intraventricular hemorrhage with associated obstructive hydrocephalus and significant hormone imbalance (hypocortisolism and hypothyroidism) were observed in one case each. In terms of disease specific complications, it was observed that although diabetes insipidus occurred in all macroadenomas, it was relatively more in macroprolactinomas 8/9 (88%). Similarly, there were more cases of CSF leaks observed in macroprolactinomas 4/5 (80%). Not surprisingly all the associated meningitis occurred in the macroprolactinoma group. The lone case of intraventricular hemorrhage was observed also in this group. It is instructive to note that the lone case of hypopituitarism manifesting as hypocortisolism and hypothyroidism was observed in the lone case of apoplexy whereas dyselectrolytemia was more associated with the non-functional macro adenoma. In terms of overall outcome 18/22 were discharged (82%), while mortality was 4/22 (18%) due to meningitis in two cases, IVH/obstructive hydrocephalus and dyselectolytemia one case each.

Figure 1:Overall recorded complication.

Table 1: Diagnostic indications for surgery.

Discussion

Diabetes Insipidus (DI) was the commonest complication (59.1%) in this series of 22 patients who underwent surgery for pituitary adenoma. It is caused by insufficient ADH activity on the renal tubules resulting in excessive loss of urine (>250cc/ hr in adults and >3cc/kg/hr in children) with low osmolality (<200mOsm/L) and low specific gravity (<1.003). There is also often associated high serum sodium and osmolality. In the context of pituitary surgery, the low ADH results from inadvertent injury to the posterior posterior pituitary, which is often as trivial as neuropraxia, edema and compression in the neuro-hypohysis. Hence most are transient as recorded in this study. However, it may become prolonged and even permanent in severe injuries such as in traction, avulsion of hypophyseal vessels and infarction of the neurohypophysis. If not treated DI results in life threatening fluid and electrolyte imbalance. In this study, DI was observed more in the Macroadenomas especially the macroprolactinomas but in another series, it was observed more in apoplexy [9]. The reasons are not clear but may be related to infarction and edema extending to the neurohypophysis and hypothalamus in apoplexy. It may also be related to sheer size and extensive manipulations required in removal of macroadenomas. It therefore becomes imperative to adopt a proactive approach towards DI management in the perioperative management of a pituitary surgery patient. Altough DDAVP is always handy, it is ever hardy used in our series because most are transcient and fluid replacement usually suffice.

The second most important complications in this study are CSF leak and as reported above occurred more in macroprolactinomas. It does appear as though CSF leak is related to tumor type and size in this study but in other studies, Surgical revision, tumor consistency, and tumor margins were independently associated with intra-operative leaks, while the tumor size, consistency, and margins were risk factors of postoperative leaks [10]. However, Shiney et al. [11]. in their retrospective review found no such relationship of postoperative CSF leak with tumor size. Perhaps surgical technical finesse plays an important role but the changes in integrity of the diaphragm sella from tumor size or exposure to certain pituitary hormones may be a factor to be considered. However, they key concern with CSF leak is the high potential for morbidity and mortality from the most dreaded complication meningitis. This fistula creates a direct conduit between the mixed microorganism laden naso and oropharynx and the subarachnoid space. The strategies we have deployed in our service to manage CSF leaks include judicious use of lumbar drains, repair of sellar floor with fat graft and tissue glue, and timely deployment of antibiotics (metronidazole and ceftriaxone).

Post-operative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV) is not a lifethreatening complication but results in considerable distress to the patients. It was reported in only three cases (13.6%) in this series but its incidence post craniotomy may be as high as 50% [12]. However, incidence of PONV following trans sphenoidal surgery is quite low. There is yet no plausible explanation, however, residual effects of anesthetic drugs, opiod analgesics and surgical manipulations on the dural lining of the skull base and postoperative edema are possible explanations. Because of emergent presentation, it should be aggressively managed with steroids and antiemetics (Dexamethasone) resulting in some protection from PONV. The most devastating of all the complications was reactionary hemorrhage resulting in intraventricular hemorrhage and acute obstructive hydrocephalus. It has a high morbidity and mortality and was observed in one case in this series which eventually resulted in one of the recorded mortality. It was reported in 2.2% in transcranial approach and up to 10% in trans sphenoidal surgery [13]. It is a complication that should be rather avoided by meticulous, image guided sellar floor dissection and tumor excision followed by impeccable hemostasis. Residual tumor should be avoided at all cost because they potentially bleed into the tumor bed and dissect into the third ventricle through the hypothalamus. This sparks off acute obstruction to free passage of CSF to cause deterioration to coma. Emergency external ventricular drainage become necessary to halt any further slide but a prolonged ICU stay becomes inevitable (Table 2).

Table 2: Disease specific complications.

Dyselectrolytemia in pituitary surgery are mainly seen in the form of serum sodium imbalances. Hypernatremia is a manifestation of DI and hyponatremia is because of Syndrome of Inappropriate Anti Diuretic Hormone Secretion (SIADH), hypocortisolism and rarely because of cerebral salt wasting syndrome [14]. Whereas hypernatremia manifests (due to DI) during early postoperative period, hyponatremia usually presents after few days in the postoperative period [15]. as manifestations of the different phases of triple phase response post pituitary surgery. Hypokalemia too can occur, but its incidence is very low. As displayed on the results, all were recorded in this study and the key was high index of suspicion and daily biochemical estimations in the early post op days. An unrecognized or improperly treated Na+ imbalance may result in catastrophe. Kristof et al. [16] showed that water and electrolyte (Na+) disturbances occurred in 75% of their patients following transsphenoidal surgery which is also in agreement to this study. Early recognition and proactive management usually suffice in reducing the morbidity and mortality associated. The lone case of pan hypopituitarism was observed in apoplexy who presented three days post event, and following successful surgery, he became increasingly lethargic on subsequent outpatient follow up. Pituitary hormone profiling confirmed hypo cortisol and hypothyroid status. It is imperative to note that on the advice of the endocrinologist, he first had exogenous cortisol replacement and restoration of satisfactory serum cortisol levels before adding L- thyroxine replacement. This is imperative to avoid any storming, Addisonian crisis. In another related study in this environment by Ugwuanyi the commonest post-op complication was nasal bleeding in 6/28 (21%) but most important was DI in 3/28 (10.7%) and CSF leak in one case (3.5%). In spite of all perioperative proactive management measures a mortality of 4/22 (18%) was a cause for concern but that was found to be due to meningitis complicating CSF leak in two cases, intraventricular hemorrhage and dyselectrolytemia in one case each. It becomes expedient that more stringent perioperative and post-operative active surveillance and vigilance must be instituted in order to ensure improved safety and outcome towards the expected low morbidity and mortality in pituitary surgery.

Conclusion

Pituitary surgery is a safe procedure, but it does carry some risks of various postoperative complications which must be considered during pre-op consent discussion and all through the operative and post-operative management period. In this series it is also important to note the higher occurrence of some complications on various groups and how tumor size and pathology may be the contributory factor for these findings. In this way, these could be anticipated and possibly avoided when planning and executing these operations to maintain the usually low morbidity and mortality levels.

References

- Jane JA, Sulton LD, Laws ER (2005) Surgery for primary brain tumors in US academic training centers: results from the residency review committee for neurological surgery. J Neurosurg 103(5): 789-793.

- Wilson CB (1992) Endocrine innactive Pituitary Adenomas. Clin Neurosurgery 38: 10-31.

- Liu JK, Weiss MH, Couldwell WT (2003) Surgical approaches to pituitary tumors. Neurosurg Clin N Am 14(1): 93-107.

- Cushing H (2010) Surgical experiences with pituitary disorders. JAMA 63: 1515-1525.

- Dott NM, Bailey P (1925) A consideration of the hypophysial adenomata. Br J Surg 13(50): 314-366.

- Guiot G, Arfel G, Brion S (1912) Adénomes hypophysaires. Masson Paris p. 276.

- Griffith HB, Veerapen RA (1987) A direct transnasal approach to the sphenoid sinus technical note. J Neurosurg 66(1): 140-142.

- Manninen PH, Raman SK, Boyle K, Beheiry H (1999) Early postoperative complications following neurosurgical procedures. Can J Anesth 46(1): 7-14.

- Tumul C, Hemanshu P, Parmod K. Bithal, Bernhard S (2014) Immediate postoperative complications in transsphenoidal pituitary surgery: A prospective study. Saudi J Anaesth 8(3): 335-341.

- Han ZL, He DS, Mao ZG, Wang HJ (2008) Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea following trans-sphenoidal pituitary macroadenoma surgery: experience from 592 patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 110(6): 570-579.

- Shiley SG, Limonadi F, Delashaw JB, Barnwell SL, Andersen PE, et al. (2003) Incidence, etiology, and management of cerebrospinal fluid leaks following trans-sphenoidal surgery. Laryngoscope 113(8): 1283-1288.

- Fabling JM, Gan TJ, Moalem HE, Warner DS, Borel CO (2002) A randomized, double-blind comparison of ondansetron versus placebo for prevention of nausea and vomiting after infratentorial craniotomy. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 14(2): 102-107.

- Taylor WA, Thomas NW, Wellings JA, Bell BA (1995) Timing of postoperative intracranial hematoma development and implications for the best use of neurosurgical intensive care. J Neurosurg 82(1): 48-50.

- Sane T, Rantakan K, Poranen A, Tabtela R, Valimali M (1994) Hyponatremia after transsphenoidal surgeon for pituitary tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 79(5): 1395-1398.

- Kristof RA, Rother M, Neuloh G, Klingmüller D (2009) Incidence, clinical manifestations, and course of water and electrolyte metabolism disturbances following transsphenoidal pituitary adenoma surgery: A prospective observational study. J Neurosurg 11(3): 555-562.

- Charles U, Anthony A, Emeka N, Cyril O, Obinna A (2009) A review of visual and endocrine outcome following surgery for pituitary.

© 2022 Ugwuanyi CU. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)