- Submissions

Full Text

Techniques in Neurosurgery & Neurology

Manifestation of Defensive Processes in Basic Motor Responses: Evidence from Chinese Participants

Sha Shen*

Department of Educational Science and Technology, China

*Corresponding author: Sha Shen, Department of Educational Science and Technology, China

Submission: August 17, 2021;Published: October 14, 2021

ISSN 2637-7748

Volume4 Issue4

Abstract

Previous studies have found that, in the Western culture, the defensive processes of participants with relatively avoidant attachment tendencies are manifested in their basic motor responses. Studies have also shown that there are cultural differences in attachment behaviors. Therefore, it is worth examining whether the defensive processes of relatively avoidant individuals are manifested in their basic motor responses in the Eastern culture as well. In the present study, 122 Chinese undergraduates were recruited as participants. They were shown real pictures of their mothers and were asked to push or pull a lever as quickly as possible. The results showed that participants with relatively avoidant tendencies inclined to pushed the lever when their mother’s picture was presented. This suggested that, in the Eastern culture, the basic avoidant motivation of relatively avoidant individuals was also automatically activated while processing attachment-related stimuli. In addition, this automatic activation was also manifested in basic, motor-specific ways.

Keywords: Defensive processes; Avoidant attachment; Cultural difference

Introduction

What do you do when you are alone and helpless? Humans beings are born with a series of

proximity behaviors such as crying that motivated by the innate attachment system in order

to protect us from kinds of threats and reduce stress. If the proximity behaviors are positively

responded to most of the time by the primary caregiver, the optimal functioning of attachment

system will be facilitated. We will gradually realize we are worthy of love, when needed we

can rely upon others and forms secure attachment. Conversely, if the proximity behaviors are

ignored or respond negatively, we will learn we are unworthy of love, when needed can’t rely

upon others and are more likely to develop the avoidant attachment. There are significant

individual differences between secure and avoidant attachment [1-3]. Individuals with secure

attachment tend to establish intimate relationships with others [4], while individuals with

avoidant attachment incline to deactivate their attachment system [5-9]. They are less likely

to establish intimate relationships with others [10] and rarely ask for help even in times of

stress. The individuals with avoidant attachment have the same attachment needs as secure

ones [11,12], how do they deactivate their attachment needs? The studies showed they tend

to use defensive strategies to minimize attachment needs for protect them from reviewing a

past traumatic experience related to attachment. Since proximity seeking behaviors are not

viable options for individuals with avoidant attachment, when process attachment-related

stimuli, the primary goal is to exclude attachment-information from awareness. To achieve

this goal, there are two kinds of defensive strategies can be used: minimize attention to

events may trigger attachment and avoid getting involved in events related to attachment

that have already occurred [13]. Studies have found that the defensive processes of relatively

avoidant individuals are manifested in their basic, motor-specific responses [14]. In the

experiment by Fraley and Marks, the researchers first measured the attachment-related

anxiety and avoidance of each participant using the Experiences in Close Relationships

Revised questionnaire [13]. Next, participants were presented with three types of words, the word “mom,” positive words, and negative words. The participants’

task was to respond quickly with a lever, after seeing all the words.

The following two types of task conditions were used: pushing

and pulling the lever. In the data analysis, they first calculated the

participants’ reaction time differences between the push vs. pull

conditions for positive words, negative words and the word “mom”.

Then, the difference was used to carry out a regression analysis on

attachment-related anxiety and avoidance. It was found that when

the word “mom” was presented, relatively avoidant individuals

tended to push the lever away from their body. These experiments

suggested that when relatively avoidant individuals process

attachment-related stimuli, their defensive processes are manifest

in basic, motor-specific ways.

In the experiment described above, the participants belonged

to the Western culture (Americans). Studies indicated cultural

differences in attachment behavior [15-17]. Specifically, compared

with the Western culture, individuals in the Eastern culture are

more inclined to use defensive strategies and exhibit a higher level

of avoidant attachment. Leung et al. [17] performed a comparative

analysis of Anglo-Australian undergraduates in the Western culture

and Chinese undergraduates in the Eastern culture, and they

found that, compared to those in the Western culture, individuals

in the Eastern culture were more likely to use defensive strategies

such as rejection. Wei M et al. [16] compared the attachment

characteristics in the Western and Eastern cultures and reported

that, as compared to those in the Western culture, individuals in

the Eastern culture showed a higher level of attachment avoidance.

Therefore, the present study hypothesized that the defensive

processes of relatively avoidant individuals in the Eastern culture

would manifest in their basic motor responses. Based on the study

by Fraley [18], the above hypothesis was tested in the present study

using Chinese undergraduates as participants, the mother as the

object of attachment and pictures as experimental materials. If the

hypothesis is true, then the relatively avoidant Chinese individuals

would also be inclined to push the lever when they are presented

with pictures of their own mothers.

Material and Method

Participants

In total, 122 undergraduates participated in this experiment and were reimbursed after the experiment at the end. The mean age of the participants was 20.89 years (SD=1.44 years). Among them, 71 were females and 51 were males. All participants were right-handed. The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Northwest Minzu University. All participants gave written informed consent.

Procedure and material

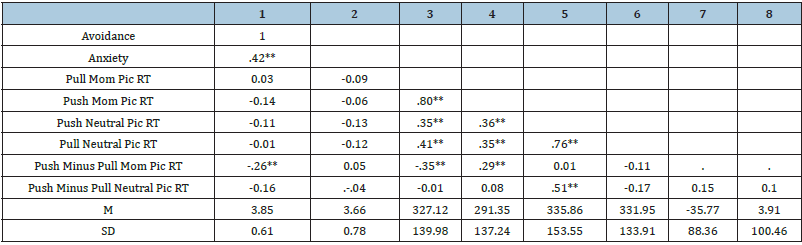

All participants first completed a questionnaire containing questions on demographic characteristics and intimate relationship experiences after entering the laboratory. The Experiences in Close Relationships Revised Questionnaire was used. The subjects were required to evaluate their consistency with the content described in the question and scored on a scale of 1 (complete non-conformance) to 7 (complete conformance). The questionnaire comprises 36 items, 18 items in each dimension of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance, and the average score is calculated as the score of each dimension. Attachment anxiety concerns the anxiety level that individuals experience toward potential rejections from others. Compare with the ones experience lower levels of anxiety, people with high levels of anxiety experience higher levels of negative emotions. Attachment avoidance concerns the level of comfort that individuals experience in intimate relationships. Individuals with a high degree of attachment avoidance tend fear intimate relationships and they may refuse to trust others; while individuals with a low degree of attachment avoidance are willing to establish intimate relationships with others. Individuals with typical secure attachments will have relatively lower scores on both dimensions. In this study, the internal consistency of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were 0.77 and 0.63 respectively. The correlation between the two dimensions was 0.42; hence, they were simultaneously included in the equation during the regression analysis. The experimental materials were 11 photos, one of which was the photo of the participant’s mother, while the other 10 were neutral pictures. The picture of the participant’s mother was provided by the participant before the experiment. Neutral images were obtained from the Chinese Affective Picture System (CAPS) Huang [19] All images had a resolution of 100 pixels per inch and a size of 4.55 x 5.55 cm2. During the actual experiment, participants were first asked to fill in the questionnaire. Then, they were asked to sit in front of a computer. A 7.23-inch lever was placed in front of their right hand. The experimenter then informed the participants that they would see some pictures on the computer. Their task was to push or pull the lever as quickly as possible after seeing the pictures. The experiment included two stages, Block A and Block B. In Block A, the 11 photos were randomly presented in succession (Mother’s picture can’t appear continuously). Before each photo was presented, a fixation point was shown in the center of the screen, then the picture was presented, and the participant was asked to push the lever as quickly as possible. In Block B, the same 11 photos were randomly presented in succession, but the participants were asked to pull the lever, as quickly as possible, after seeing the pictures. To balance the order effect, half the participants were asked to complete Block A and then Block B (and vice versa). The computer automatically recorded the time between the appearance of the picture and the participant’s push or pull action. After each trial, the participants were asked to re-center the lever. There was a random delay of 5-7 seconds between any two trials. The mean, standard deviation, and correlation coefficients of the variables in this study have been shown in Table 1.

Result

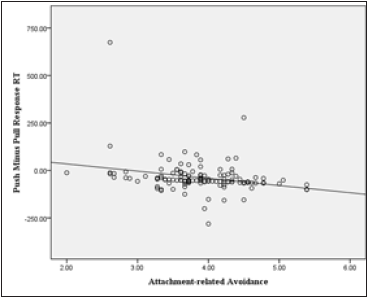

We first calculated the difference in the mean reaction times between the push and pull conditions for the five trials when the participants were presented with their mother’s pictures. Then, the difference was used to carry out a regression analysis on attachment-related anxiety and avoidance. The results showed that the model was significant, F(2,121)=6.39, p<.01, R2=10. Therefore, the null hypothesis that the whole model is not significant is rejected, indicating that the whole model is significant. When relatively avoidant individuals were presented with pictures of their mother, compared to pull lever they were faster to push (B=-49.20, SE=13.92, β=-.34, p <.01). This association has been illustrated in Figure 1. Attachment-anxiety (B=21.30, SE=10.90, β=9.19, p>.05) and the constant term (B=75.93, SE=52.46, p>.05) could not significantly predict this variable. We performed further regression analyses to test whether attachment-related avoidance and anxiety could significantly predict the differences in reaction times (i.e., the difference in average reaction time between pushing and pulling the lever when presented with neutral pictures; descriptive statistics have been shown in Table 1). The results showed that the model was not significant, F (2,121) =1. 663, p=.19. Therefore, the null hypothesis that the whole model is not significant is accepted, indicating that the whole model is not significant, that is, neither attachment avoidance nor attachment anxiety can significantly predict the difference. The results of this study showed that, in the Eastern culture, when relatively avoidant individuals process attachment-related stimuli, their defensive processes are also manifested in their basic motor responses.

Figure 1: Prediction of the difference in reaction times between pushing and pulling the lever by attachment

avoidance under controlled levels of attachment-anxiety.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables

Note: Variables 5-6 represent the mean reaction times to neutral images in the conditions of push and pull. Variable 8 represents the difference in mean reaction times to neutral images in the push vs. pull conditions. Reaction times have been reported in milliseconds. **represents correlations with a significance level of above 0.01.

Discussion

In this study, Chinese undergraduates were recruited as participants to explore whether, in those with an Eastern cultural background, the defensive processes of participants with relatively avoidant attachment were manifested in their basic motor responses. The results indicated that when participants were presented with pictures of their mothers, relatively avoidant individuals were more inclined to push the lever. This suggests that, for relatively avoidant participants in the Eastern culture, the basic avoidant motivation is automatically activated while processing attachment-related stimuli. Furthermore, this automatic activation was manifested in basic, motor-specific ways. The results of this study further supported the findings of Fraley [18], who reported that when attachment-related stimuli were presented to Americans in the Western culture, relatively avoidant participants tended to push the lever. The present study further found that when attachment-related stimuli were presented to Chinese people in the Eastern culture, relatively avoidant individuals were also more inclined to push the lever. Future studies should focus on whether other objects of attachment (such as father, grandfather, grandmother, etc.) could activate the basic avoidant motivation of relatively avoidant individuals. Additionally, studies should examine how this basic avoidant motivation is manifested in their basic motor responses. An individual’s object of attachment also includes important figures other than the mother [20]. Therefore, it is worth asking whether these different objects of attachment can automatically activate the individual’s basic avoidance motivation and are manifested in their basic motor responses. Future studies should also focus on whether the defensive processes of individuals with different attachment types all are manifested in their basic motor responses. Individuals with different attachment types display different attachment behaviors and adopt different defensive strategies [21-23]. Therefore, it would be meaningful to explore if the defensive processes of individuals with different attachment types are manifested in the same way. For example, future studies could explore if the defensive processes of individuals with secure attachment would also be manifested in their basic motor responses when a stimulus that characterizes the object of attachment is presented.

Funding

Key Laboratory of China’s Ethnic Languages and Information Technology of Ministry of Education, Northwest Minzu University, Lanzhou, Gansu, 730030, China (No.: KFKT202013, KFKT202016, KFKT202012, 1001161310). The Young Doctor Foundation of Higher Education in Gansu Province “Research on the educational effect mechanism of the socialist core value ‘unity of knowing and doing’ of college students for nationalities in the new era”(No.: 2021QB-071). Gansu Province Education Science “14th Five- Year Plan” 2021 annual project(The core behavior of children’s patriotism in the new era).The Ministry of Education -- China Mobile Scientific Research Fund 2018 Project “Research on the Effective Mechanism and Promotion Strategy of Promoting the Balanced Development of Compulsory Education by Using ‘Three Classrooms’” (No.: MCM20180612). Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities “Research on influencing factors of online education in post-epidemic era”(No.: 31920210125).

References

- Hirst SL, Hepper EG, Tenenbaum HR (2019) Attachment dimensions and forgiveness of others: A meta-analysis. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 36(11-12): 3960-3985.

- Martin AA, Hill PL, Allemand M (2019) Attachment predicts transgression frequency and reactions in romantic couples’ daily life. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 36(8): 2247-2267.

- Van Monsjou E, Struthers CW, Khoury C, Guilfoyle JR, Young R, et al. (2015) The effects of adult attachment style on post‐transgression response. Personal Relationships 22(4): 762-780.

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR (2007) Individual differences in attachment system functioning: Development, stability and change. Attachment in Adulthood: Structure, Dynamics, and Change, pp. 116-146.

- Chun DS, Shaver PR, Gillath O, Mathews A, Jorgensen TD (2015) Testing a dual-process model of avoidant defenses. J Research in Personality 55: 75-83.

- Donges US, Zeitschel F, Kersting A, Suslow T (2015) Adult attachment orientation and automatic processing of emotional information on a semantic level: A masked affective priming study. Psychiatry Res 229(1-2): 174-180.

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR (2007) Individual differences in attachment system functioning: Development, stability and change. Attachment in Adulthood: Structure, Dynamics, and Change, pp. 116-146.

- Zhai J, Chen X, Ma J, Yang Q, Liu Y (2016) The vigilance-avoidance model of avoidant recognition: An ERP study under threat priming. Psychiatry Research 246: 379-386.

- Zheng M, Zhang Y, Zheng Y (2015) The effects of attachment avoidance and the defensive regulation of emotional faces: Brain potentials examining the role of preemptive and postemptive strategies. Attach Human Dev 17(1): 96-110.

- Gillath O, Karantzas G (2015) Insights into the formation of attachment bonds from a social network perspective. In Bases of Adult Attachment, pp. 131-156.

- Mikulincer M, Gillath O, Shaver PR (2002) Activation of the attachment system in adulthood: Threat-related primes increase the accessibility of mental representations of attachment figures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83(4): 881-895.

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR (2019) Attachment orientations and emotion regulation. Curr Opin Psychol 25: 6-10.

- Fraley RC, Waller NG, Brennan KA (2000) An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 78(2): 350.

- Lin HH, Chew PYG, Wilkinson RB (2017) Young adults’ attachment orientations and psychological health across cultures: The moderating role of individualism and collectivism. Journal of Relationships Research.

- Mesman J, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Sagi Schwartz A (2016) Cross-cultural patterns of attachment. Handbook of attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications, pp. 852-877.

- Wei M, Russell DW, Mallinckrodt B, Zakalik RA (2004) Cultural equivalence of adult attachment across four ethnic groups: Factor structure, structured means, and associations with negative mood. Journal of Counseling Psychology 51(4): 408-417.

- Leung C, Moore S, Karnilowicz W, Lung CL (2011) Romantic relationships, relationship styles, coping strategies, and psychological distress among Chinese and Australian young adults. Social Development 20(4): 783-804.

- Fraley RC, Garner JP, Shaver PR (2000) Adult attachment and the defensive regulation of attention and memory: The role of preemptive and postemptive processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 79: 816-826.

- Bai L, Ma H, Huang YX, Luo YJ (2005) The development of native Chinese affective picture system a pretest in 46 college students. Chin Ment Health J 19(11): 719-772.

- Ainsworth MS (1979) Infant mother attachment. Am Psychol 34(10): 932-937.

- Ein Dor T (2015) Attachment dispositions and human defensive behavior. Personality and Individual Differences 81: 112-116.

- Kirsh SJ, Cassidy J (1997) Preschoolers' attention to and memory for attachment‐relevant information. Child Development 68(6): 1143-1153.

- Taikh A, Hargreaves IS, Yap MJ, Pexman PM (2015) Semantic classification of pictures and words. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 68(8): 1502-1518.

© 2021 Sha Shen. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)