- Submissions

Full Text

Surgical Medicine Open Access Journal

COVID Pneumonia with Typhoid Versus Calcular Cholecystitis; Escalation Drama among Internists and Surgeons; Seriousness and Interpretation: A Case Report in Surgery, Infectious Diseases, Chest, and Critical Care Medicine

Elsayed YMH*

Critical Care Unit, Kafr El-Bateekh Central Hospital, Egypt

*Corresponding author: Yasser Mohammed Hassanain Elsayed, Critical Care Unit, Kafr El-Bateekh Central Hospital, Damietta Health Affairs, Egyptian Ministry of Health (MOH), Damietta, Egypt

Submission: January 5, 2022Published: March 10, 2022

ISSN 2578-0379 Volume4 Issue5

Abstract

Rationale: Accurate, précised, and correct diagnosis is one of the most important cornerstones in clinical medicine. Pandemic COVID-19 virus infection represents the top widely spread disease in the current time. Acute cholecystitis is a common surgical disease. There is no more difficulty in its diagnosis. Typhoid fever is considered a serious multisystemic infection. Sometimes, the physician, surgeon, and internist deal with the patient based on his specialty view neglecting the other specialties. Undoubtedly, differential diagnosis is a base of medicine. Patient concerns: A 54-year-old, housewife, married, Egyptian female patient was initially diagnosed with acute calcular cholecystitis neglecting COVID-19 pneumonia with typhoid fever. Diagnosis: COVID pneumonia with typhoid fever versus calcular cholecystitis; escalation drama among internists and surgeons. Interventions: Abdomen ultrasound, electrocardiography, oxygenation, non-contrast chest CT, widal test, and echocardiography. Outcomes: Good response and better outcomes despite the presence of several remarkable risk factors were the results. Lessons: Combination of acute calcular cholecystitis, COVID-19 pneumonia, and typhoid fever is an extreme association. Accurate, précised, correct diagnosis with respecting the differential diagnosis surely will save the patient life. The escalating method for the cases among internists and surgeons is serious and may cause death for the patient. Co-operation is the base. The focusing of the specialist on his especially on the examination for the case should be changed. But he should deal with a case as a general case whatever the diagnosis.

Keywords: COVID-19 pneumonia, Typhoid fever, Cholecystits, Gallbladder disease, Internists, surgeons

Abbreviations:AAC: Acute Acalculous Cholecystitis; COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease 2019; DD: Differential Diagnosis; ECG: Electrocardiogram; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; O2: Oxygen; SGOT: Serum Glutamic-Oxaloacetic Transaminase; SGPT: Serum Glutamic-Pyruvic Transaminase; VR: Ventricular Rate; CTD: Connective Tissue Disease; AC: Acalculous Cholecystitis; POC: Physician Outpatient Clinic; BP: Blood Pressure; CBC: Complete Blood Count

Introduction

Differential Diagnosis (DD) is a process in which a doctor can distinguish among two or more medical disorders that could be behind a person’s symptoms [1]. Nevertheless, several conditions share some of the same or analogous symptoms. This makes the underlying condition must be directed indifficult straightforward diagnoses. So, using a non-differential diagnostic approach may be essential and helpful if there are multiple potential causes to consider [1]. COVID-19 infection needs a focus on appointed challenges in diagnosis and the yielding of improving diagnostic precision and promptness [2]. The ability to make a data-driven diagnosis is a substantial skill in the healthcare dictionary. Improving diagnostic accuracy is based on improving how you collect and use healthcare data in a suitable situation. Data should possess high quality and accuracy, be tailored to the patient’s individuality, and support complex clinical decisions [2]. Acute cholecystitis is an acute inflammatory process of the gallbladder [3]. It is commonly due to gallstones. Ischemia, motility disorders, chemical injury, infections (microorganisms, protozoa, and parasites), Connective Tissue Disease (CTD), and allergy are other implicated causes [1]. Acute cholecystitis cases represent about 3%-10% of all cases of abdominal pain [1]. Cholecystolithiasis is nearly 90%-95% of all causes of acute cholecystitis, but Acalculous Cholecystitis (AC) is the remaining 5%–10% [3]. Acute cholecystitis is the most common complication in cholelithiasis [3]. According to the annual natural history of cholelithiasis, serious symptoms or complications such as (acute cholecystitis, acute cholangitis, clinical jaundice, and pancreatitis) were reported in 1%-2% of asymptomatic cases but in 1%-3% of mild symptomatic cases [4].

According to 13 reported international studies; the mortality rate in acute cholecystitis was between 0-42.74% [3]. It may be complicated with perforation of the gallbladder, biliary peritonitis, pericholecystic abscess, and biliary fistula [3]. Acute cholecystitis is especially dangerous during a serious illness or following major surgery, however, whether associated with gallstones or more typically not Acute Acalculous Cholecystitis (AAC) [5]. Acute cholecystitis may be a carrier of typhoidal and non-typhoidal Salmonella during active diarrheal disease [5]. The mortality rate remains at least 30% due to the diagnosis of AAC is still challenging to make, affected patients are critically ill, and the disease itself can proceed quickly due to the high incidence of gangrene (about 50%) and perforation (approximately 10%) [6]. Abdomen ultrasound; specifically, the gallbladder is the most accurate method to diagnose AAC in critical-ill patient [5]. Typhoid fever is a highly critical, infectious, and dangerous illness. It is caused by Salmonella enterica serovars Typhi, Paratyphi A, Paratyphi B, and Paratyphi C can be collectively categorized as typhoidal Salmonella, despite some being assembled as non-typhoidal Salmonella [7]. Typhoid fever and paratyphoid fever may present with fever, weakness, epigastric pain, headache, diarrhea or constipation, cough, and loss of appetite [8]. Timely and accurate diagnosis and treatment of typhoid fever in the community is needed to avert complications requiring hospitalization, and death [9]. The Widal test is basic and cheap to perform is still widely utilized in many countries [10]. Bronchitis, pneumonia, pharyngitis, cholecystitis, hepatitis, intestinal perforation, intestinal hemorrhage, anemia, disseminated intravascular coagulation, shock, asymptomatic ECG changes, myocarditis, encephalopathy, meningitis, psychotic states, delirium, impairment of coordination, impairment of coordination, seizures, miscarriage in pregnant women, and chronic carriage are reported complication with typhoid [11].

Case Presentation

A 54-years-old, housewife, married, Egyptian female patient was presented to the Physician Outpatient Clinic (POC) with fever, tachypnea, abdominal pain, and vomiting. He gave a recent history of palpitations, fatigue, severe headache, constipation, dry cough, generalized body aches, anorexia, and loss of smell 3 days ago. The abdomen pain was sharp pain in the upper right-hand side radiates towards the right shoulder and the pain worse on deep breathing. There is a local tender with a positive murphy’s sign. There is a recent contact with a confirmed case of COVID-19 pneumonia 15 days ago. She gives a history of fever, vomiting, and abdominal pain within 10 days after eating Ice-cream. The patient was escalating among internists and surgeons for about 15 days with hesitating in the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis. The internists claim that is the case is irrelevant to them but the surgeons wish to be managed the patient initially by internists. The patient denied a history of other relevant diseases, drugs, or other special habits. Informed consent was taken. Upon general physical examination; generally, the patient was tachypneic, irritable, distressed, with a regular rapid pulse rate of VR; 100bpm, Blood Pressure (BP) of 100/70mmHg, respiratory rate of 26bpm, the temperature of 39.5°C, and pulse oximeter of oxygen (O2) saturation of 90%.

The white coated-tongue was noted. Currently, the patient hardly refused the hospital referral. She was initially managed at home with COVID-19 pneumonia with typhoid fever. Initially, the patient was treated with O2 inhalation by O2 cylinder (100%, by nasal cannula, 5L/min; as needed). The patient was maintained treated with cefotaxime; (1000mg IV every 8 hours), azithromycin tablets (500mg, OD), oseltamivir capsules (75mg, BID only for 5 days), and paracetamol (500mg IV every 8 hours as needed). SC enoxaparin 80mg, BID), aspirin tablet (75mg, OD), clopidogrel tablets (75mg, OD), hydrocortisone sodium succinate (100mg IV every 12 hours), and ciprofloxacin tablets (500mg, BID) for 5 days were given. Ringer solution (500ml; TDS) was added. The patient was daily monitored for temperature, pulse, blood pressure, and O2 saturation. The fever was intermittently elevated thorough the first week.

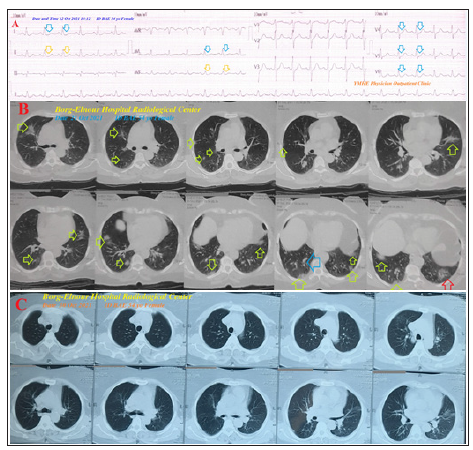

Abdominal ultrasound was done within 10 days of the presentation to the POC within 5 days of escalating among internists and surgeons showing thick wall gall bladder with enlarged two stones (Figure 1). The initial ECG tracing was done on the day of the presentation to the POC within 15 days of escalating among internists and surgeons showing sinus tachycardia of VR; 108. There is ST-segment depression in both anterolateral (I, aVL, and V4-6) and inferior leads (II and aVF) (Figure 2A). Laboratory workup was done during the third day of the presentation. The initial Complete Blood Count (CBC); Hb was 12.8g/dl, RBCs; 5.3*103/ mm3, WBCs; 11.10*103/mm3 (Neutrophils; 69.2%, Lymphocytes: 27.3%, Monocytes; 3.5%, Eosinophils; 0% and Basophils 0%), Platelets; 184*103/mm3. S. Ferritin was high; 171.82ng/ml. D-dimer was high (0.670ng/ml). CRP was high (16.9g/dl). LDH was high (489.7U/L). SGPT was normal (21U/L), SGOT was normal (18U/L). Serum albumen was low (2.5gm/dl). Serum creatinine was normal (0.88mg/dl) and blood urea was normal (38.21mg/dl). RBS was normal (119mg/dl). Plasma sodium was normal (136mmol/L). Serum potassium was normal (3.7mmol/L).

Figure 1: Abdominal ultrasound was done within 10 days of the presentation to the POC within 5 days of escalating among internists and surgeons of showing thick wall gall bladder (lime arrows).with enlarged two stones (red arrows).

Figure 2: A. ECG tracing was done on the day of the presentation to the POC within 15 days of escalating among internists and surgeons of showing sinus tachycardia of VR; 108. There is ST-segment depression in both anterolateral (I, aVL, and V4-6; light blue arrows) and inferior leads (II and aVF; orange arrows). B. Chest CT without contrast was done on the day of the presentation to the POC within 15 days of escalating among internists and surgeons showing bilateral multiple ground-glass opacities (lime arrows) with halo sign (light blue arrow) and reversed halo signs (red arrow). C. Chest CT without contrast was done within 10 days of the above CT showing dramatic improvement of the above abnormalities.

Ionized calcium was normal (1.09mmol/L) and total calcium was normal (10.7mg/dl). The direct agglutination test for Widal was; positive for; Typhi (O); 1/80, Typhi (H); 1/160, Paratyphi (A); 1/40, Paratyphi (B); 1/40. The troponin test was negative (0.05U/L). Chest CT without contrast was done on the day of the presentation to the POC within 15 days of escalating among internists and surgeons showing bilateral multiple groundglass opacities with halo sand reversed halo sign (Figure 2B). Chest CT without contrast was repeated within 10 days of the above CT showing Chest CT without contrast was done within 10 days of the above CT showing dramatic improvement of the above abnormalities (Figure 2C). Echocardiography was done during the tenth day of the presentation with EF; 70% showed no detected abnormalities. Cholecystectomy is currently postponed until enough rehabilitation time for both COVID pneumonia with typhoid fever. COVID pneumonia with typhoid fever versus calcular cholecystitis; escalation drama among internists and surgeons was the most probable diagnosis. The patient was dramatically improved within 7 days of at-home management. The patient was continued on aspirin tablets (75mg, OD) and paracetamol tablets (500mg, TID, as needed). (5mg; OD). Further surgical, infectious, and chest follow-up was advised.

Discussion

Overview

A 54-year-old, house wife, married, Egyptian female patient was initially diagnosed as an acute calcular cholecystitis neglecting COVID-19 pneumonia with typhoid fever.

Primary objective

The primary objective for my case study was the presence of a patient who presented to surgeons and internists in the physician outpatient clinics with acute calcular cholecystitis with undiagnosed COVID-19 pneumonia with typhoid fever.

Secondary objective

The secondary objective for my case study was the question of

how did you manage the case at home?

a) There is an initial undoubtedly presentation of acute

cholecystitis with upper right abdominal pain that radiates

towards the right shoulder, worse on deep breathing, with a

local tender with a positive murphy’s sign, and confirmed

with abdominal ultrasound are a guide for acute calcular

cholecystitis. The severity of the case presentation pushes

both surgeons and internists to fear to deal with the case.

b) The case had entered in deterioration due to delay in accurate

diagnosis and neglect the case DD or possible association.

c) Constellation of the history of fever, vomiting, and abdominal

pain within 10 days after eating Ice-cream, the existence of

severe headache, white-coated tongue, constipation, and widal

test gives a good directory of possible typhoid fever.

d) Interestingly, the presence of the positive history of contact

with a confirmed COVID-19 case, bilateral ground-glass

consolidation, and laboratory COVID-19 suspicion on top of

clinical COVID-19 presentation with fever, tachypnea, dry

cough, generalized body aches, anorexia, and loss of smell will

strengthen the higher suspicion of COVID-19 diagnosis.

e) The dramatic response of the presented symptoms may

be strengthening the suggestion of associated COVID-19

pneumonia with typhoid fever.

f) A-middle age female sex, COVID-19 pneumonia, COVID-19

pneumonia, typhoid fever, and acute calcular cholecytitis are

risk factors.

g) Cholangitis was the most probable differential diagnosis for

the current case study.

h) I can’t compare the current case with similar conditions. There

are no similar or known cases with the same management for

near comparison.

i) The only limitation of the current study was the unavailability

of typhoid culture and initial paired widal test.

Conclusion and Recommendations

a) Combination of acute calcular cholecystitis, COVID-19

pneumonia, and typhoid fever is an extreme association.

b) Accurate, précised, correct diagnosis with respecting the

differential diagnosis surely will save the patient life.

c) The escalating method for the cases among internists and

surgeons is serious and may cause death for the patient. Cooperation

is the base.

d) The focusing of the specialist on his especially on the

examination for the case should be changed. But he should

deal with a case as a general case whatever the diagnosis.

Acknowledgment

I wish to thank the team nurses of the critical care unit in Kafr El-Bateekh Central Hospital who make extra-ECG copies for helping me. I want to thank my wife to save time and improving the conditions for supporting me.

References

- Sampson S, Klein J (2020) What is differential diagnosis?

- Lasalvia L, Merges R (2020) Moving toward precision in managing pandemics-5 critical domains for success in public health. Insights Series 11: 1-5.

- Kimura Y (2007) Definitions, pathophysiology, and epidemiology of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 14(1): 15-26.

- Friedman GD (1993) Natural history of asymptomatic and symptomatic gallstones. Am J Surg 165(4): 399-404.

- Barie PS, Eachempati SR (2010) Acute acalculous cholecystitis. Gastroenterol Clin N Am 39(2): 343-357.

- Barie PS, Fischer E (1995) Acute acalculous cholecystitis. J Am Coll Surg 180(2): 232-244.

- Gal-Mor O, Boyle EC, Grassl GA (2014) Same species, different diseases: How and why typhoidal and non-typhoidal salmonella enterica serovars differ. Front Microbiol 5: 391.

- CDC (2019) Typhoid fever and paratyphoid fever. Symptoms and Treatment.

- Crump JA, Sjölund-Karlsson M, Gordon MA, Parry CM (2015) Epidemiology, clinical presentation, laboratory diagnosis, antimicrobial resistance, and antimicrobial management of invasive salmonella infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 28(4): 901-937.

- Khan K, Khalid L, Wahid K, Ali I (2017) Performance of TUBEX® TF in the diagnosis of enteric fever in private tertiary care hospital Peshawar, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc 67(5): 661-664.

- Marchello CS, Birkhold M, Crump JA (2020) Complications and mortality of typhoid fever: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect 81(6): 902-910.

© 2022 Elsayed YMH. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)