- Submissions

Full Text

Surgical Medicine Open Access Journal

Giant Hepatic Artery Aneurysm: The Evil Within

Rosnelifaizur Ramely1*, Ernest Ong Cun Wang2, Lenny Suryani Safri3, Azim Idris3 and Hanafiah Harunarashid3

1Department of Surgery, School of Medical Science, Malaysia

2Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Malaysia

3Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Malaysia

*Corresponding author:Rosnelifaizur Ramely, Department of Surgery, School of Medical Science, 16150 Kubang Kerian, Kelantan, Malaysia

Submission: December 11, 2018;Published: December 19, 2018

ISSN 2578-0379 Volume2 Issue2

Introduction

Hepatic artery aneurysm (HAA) is a rare presentation, with reported incidence ranging from 0.01 to 0.2% in the general population. It is the second most common form of visceral aneurysm, comprising approximately 20% of splanchnic aneurysms. Majority of cases are asymptomatic prior to rupture. Thus, ruptured hepatic artery aneurysms carries a high mortality rate. Therefore, aggressive management of HAA is recommended upon diagnosis. We presented a case of HAA pseudoaneurysm successfully managed with surgery.

Method

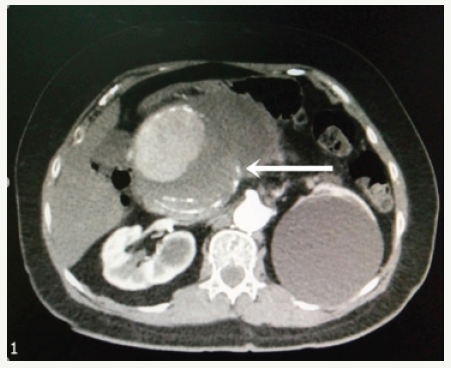

Figure 1:CT angiogram of the abdomen showing large aneurysmal sac with extensive intramural thrombus (arrowed).

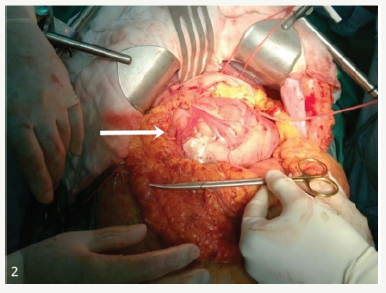

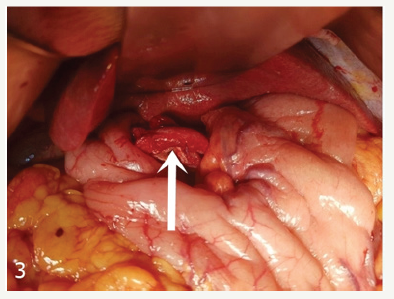

This is a case of a 56-year-old lady presented with a history of intermittent upper abdominal pain for the past one month. The pain is a dull aching pain radiating to the back and she had significant loss of weight during this period [1]. Physical examination revealed a tender, pulsatile mass at the epigastrium. Computed tomographic angiogram revealed a large saccular aneurysm of the common hepatic artery measuring 6.2x7.0x12.0cm with intramural thrombus within (Figure 1). The aneurysm sac encases both the common hepatic and splenic artery, displacing the gastroduodenal artery posterolaterally. An emergency laparotomy was performed, and intraoperative findings noted the huge aneurysm measuring 16cm have ruptured posteriorly, forming a pseudoaneurysm (Figure 2). It was released from the duodenum and omentum and excised [2]. The gastroduodenal artery adhered to the sac was ligated. The right long saphenous vein was harvested for an interposition graft between the proximal and distal common hepatic artery (Figure 3).

Figure 2:Large hepatic artery aneurysm in the lesser sac (arrowed).

Figure 3:Saphenous vein graft interposition between proximal and distal common hepatic artery (arrowed).

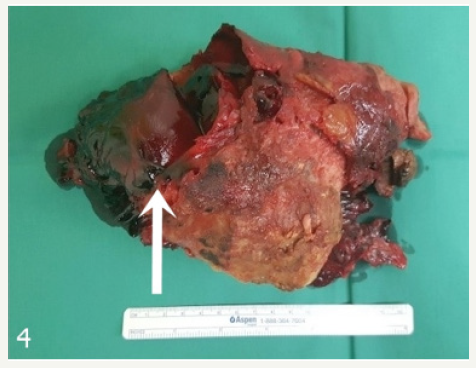

Figure 4:Excised portion of sac with rupture (arrowed).

Postoperatively, the patient developed a superficial infection at the surgical site which required surgical debridement [3]. The drain fluid biochemistry revealed raised amylase level of 70000mmol/L, which prompted the diagnosis of pancreatic fistula. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was done and her pancreatic duct was stented. Histology confirmed an aneurysmal sac with no features of vasculitis or thickening of the vasa vasorum. The patient recovered and was discharged on the day 19 postoperation.

Discussion

Despite its rarity, HAA is the second most common type of visceral aneurysm after splenic artery aneurysms. Most HAA (75- 80%) were solitary and extrahepatic. The actual etiology of HAA remains unknown, however, it is now commonly associated with atherosclerosis. Other etiologies include media degeneration, vasculitis, polyarteritis nodosa, arterial fibrodysplasia, mycotic aneurysm or iatrogenic as a consequence of liver transplantation or hepatic artery embolization. Risk factors for the development of HAA include male gender, hypertension, malignancy, peptic ulcer disease, coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, tobacco and alcohol use.

Most of the HAA are discovered incidentally and less than 20% of patients are symptomatic from complications like rupture, gastrointestinal bleeding, obstructive jaundice and cholangitis. Mortality rates at the time of rupture are reported to be as high as 40%. Risk factors for rupture include multiple HAA and nonatherosclerotic origin. Rupture of HAA in the 2cm range has been reported.

The appropriate surgical therapy depends on the location of the aneurysm, presence of collateral flow, operative risk, and clinical status. Open surgical treatment options for HAA include ligation, excision, venous grafting, synthetic grafting, and hepatic resection. Proximal and distal ligation of the hepatic artery provides a low risk solution, provided that collateral supply from the gastroduodenal artery or right hepatic artery is sufficient [4] In the case above, ligation and interposition grafting is chosen as the patient’s premorbid condition is fit for surgery, she was symptomatic prior to the surgery, which implies a possible sealed leak that requires extensive exploration to achieve distal and proximal control in the event of an overt rupture. Other described surgical techniques are laparoscopic aneurysmectomy and ligation in cases of splenic artery aneurysms [5]. Endovascular surgery is an option and plays an important role in management of intrahepatic aneurysms and in surgical candidates at high risk (Figure 4). Multiple options can be used to achieve arterial blockage which include coiling, gelfoam, particle or thrombin injection, gluing, etc, with reported success rates of 98% on initial treatment. Complications include intra-procedural aneurysmal rupture, liver ischemia, secondary recanalization and access site hematoma [6].

Conclusion

Hepatic Artery Aneurysym is a rare entity with high rates or morbidity and mortality. All symptomatic patients should be considered for treatment. Options for treatment include open or laparoscopic surgery, endovascular procedures or combination therapies.

References

- Psathakis D, Mu¨ller G, Noah M, Diebold J, Bruch HP (1992) Present management of hepatic artery aneurysms. Symptomatic left hepatic artery aneurysm; right hepatic artery aneurysm with erosion into the gallbladder and simultaneous colocholecystic fistula--a report of two unusual cases and the current state of etiology, diagnosis, histology and treatment. Vasa 21(2): 210-215.

- O’Driscoll D, Olliff SP, Olliff JFC (1999) Hepatic artery aneurysm. Br J Radiol 72(862): 1018-1025.

- Stanley CJ, Shah NL, Messina LM (1996) Common splanchnic artery aneurysms: Splenic, hepatic and celiac. Ann Vasc Surg 10(3):315-322.

- Abbas M, Fowl RJ, Stone W, Panneton JM, Oldenburg WA, et al. (2003) Hepatic artery aneurysm: Factors that predict complications. J Vasc Surg 38(1): 41-45.

- Arca MJ, Gagner M, Heniford BT, Sullivan TM, Beven EG (1999) Splenic artery aneurysms: Methods of laparoscopic repair. J Vasc Surg 30(1): 184-188.

- Fankhauser GT, Stone WM, Naidu SG, Oderich GS, Ricotta JJ, et al. (2011) The minimally invasive management of visceral artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg 53(4): 966-970.

© 2018 Rosnelifaizur Ramely. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)