- Submissions

Full Text

Surgical Medicine Open Access Journal

Perforated Appendicitis Preoperatively complicated by Multiple Intra-Abdominal Abscesses

Juan Velasquez Lopez, Tarik Zahouani* and Franscene Oulds

Department of Pediatrics, Lincoln Medical and Mental Health Center, USA

*Corresponding author:Tarik Zahouani, Department of Pediatrics, University of Maryland Medical Center, 234E, 149 St. Bronx 10451, New York, USA

Submission: June 21, 2018;Published: August 27, 2018

ISSN 2578-0379 Volume2 Issue1

Introduction

Acute appendicitis is the most common surgical emergency in the pediatric population [1]. Complications are seen in 30 to 40% of cases, and include perforated, gangrenous, intra-abdominal abscess and peritonitis [1]. The rate of perforated appendicitis is higher in children compared to adults and varies from 30% to 74% [2]. We report a case of perforated appendicitis preoperatively complicated by multiple intra-abdominal abscesses.

Case Presentation

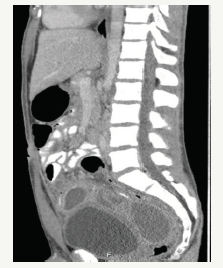

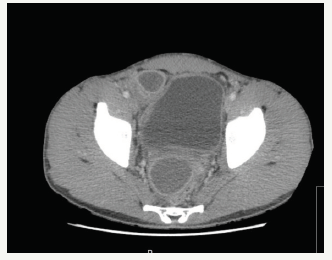

Figure 1:Multiple multiloculated abscesses throughout the lower abdomen.

A 17 y/o male, with no significant past medical history, presented with vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain for 7days. Pain progressively worsened, rated as 8/10 in intensity, located in lower abdominal quadrants, with no alleviating or exacerbating factors. Upon arrival to the ED, he had normal vital signs T: 98.3 F, HR: 98/min, BP 127/86mmHg, RR: 24/min, O2 Sat: 97% on room air. Physical examination revealed tenderness upon palpation of the lower abdomen with no guarding, rebound or rigidity. Initial laboratory tests revealed leukocytosis (WBC 23,000) with neutrophilia (90.1%), elevated procalcitonin (3.02mcg/L) and C-reactive protein (27.7mg/dl). Urinalysis showed pyuria and microscopic hematuria without nitrites or leukocyte esterase. Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast was performed, revealing multiple multiloculate abscesses throughout the lower abdomen, with no visualization of the appendix with possible extraluminal air, with mild bilateral hydronephrosis likely secondary to underlying inflammatory process (Figure 1-3).

Figure 2:Multiple multiloculated abscesses throughout the lower abdomen.

Figure 3:Multiple multiloculated abscesses throughout the lower abdomen.

Surgery was consulted, and an exploratory laparotomy was performed finding a perforated appendix with multiple intraabdominal abscesses requiring appendectomy, partial cecostomy and abdominal washout. Patient was subsequently admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit, continued IV fluids which were weaned gradually as oral intake improved. Pain was properly managed, and the patient was started on metronidazole which was discontinued after 3days, and piperacillin-tazobactam was continued to complete 10days. The patient started ambulating on post-operative day (POD) 2. The hospital course was complicated by Clostridium difficile infection on POD 5 that was successfully treated with Metronidazole. The rest of the hospitalization course was unremarkable, Jackson-Pratt drain was removed on POD 7, leukocytosis and inflammatory markers trended down and the patient was afebrile for 4days prior to discharge

Discussion

Appendicitis is the most common surgical diagnosis in children presenting with abdominal pain [3]. The clinical features of appendicitis in adolescents include fever, anorexia, vomiting, periumbilical abdominal pain that migrates to the right lower quadrant. Involuntary guarding and rebound tenderness are signs of peritoneal irritation and it is important to determine whether this irritation is localized over the RLQ, as is common in early appendicitis, or is present throughout the abdomen, as with appendiceal perforation and subsequent diffuse peritonitis [4].

Perforated appendicitis with abscess at presentation occurs in approximately 30 to 60% of children [5]. Appendiceal perforation is more common in children younger than four years of age because appendicitis is rare at that age and it is difficult to distinguish it from more common causes of abdominal pain. In contrast, appendicitis is more common in children aged 10 to 17 years with much lower rate of perforation (10%-20%) [4]. Perforation strongly correlates with duration of symptoms, and delay of treatment for more than 36 hours increases the perforation rate up to 65% [4]. Using CT in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in children increased the ability to identify complicated appendicitis preoperatively and allowed for the utilization of initial nonoperative therapy [6].

Several studies proved that percutaneous drainage with the use of antibiotics is more efficient than treatment with antibiotics alone to completely treat appendiceal abscess without an interval appendectomy [7]. Also, successful management of acute perforated appendicitis with multiple intraabdominal abscesses can be achieved with multiple minimally invasive image-guided drainage procedures [8]. However, in the case of our patient, the CT finding of preoperative multiple multiloculate abscesses throughout the lower abdomen favored a laparotomy intervention to provide the best possible outcome. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the few cases of acute appendicitis preoperatively complicated with multiple intra-abdominal abscesses in the pediatric population.

Conclusion

Appendicitis is the most common abdominal condition leading to urgent operation in children. It has a high incidence and can induce a significant morbidity in the setting of perforation, making prompt diagnosis crucial. Initial nonoperative management with ultrasound or CT guided drainage has several advantages but the need for surgical intervention should always be evaluated in case to case basis.

References

- Zouari M, Abid I, Sallami S (2017) Predictive factors of complicated appendicitis in children. American Journal of Emergency medicine 35: 1982-1983.

- Williams R, Blakely M, Fischer P, Streck CJ, Dassinger MS, et al. (2009) Diagnosing ruptured appendicitis preoperatively in pediatric patients. J Am Coll surg 208(5): 819-825.

- Scholer SJ, Pituch K, Orr DP, Dittus RS (1996) Clinical outcomes of children with acute abdominal pain. Pediatrics. 98(4 Pt 1): 680-685.

- Bundy DG, Byerley JS, Liles EA, Perrin EM, Katznelson J, et al. (2007) Does this child have appendicitis? JAMA 298(4): 438-451.

- Furuya T, Inoue M, Sugito K, Goto S, Kawashima H, et al. (2015) Effectiveness of interval appendectomy after conservative treatment of pediatric ruptured appendicitis with abscess. Indian J Surg 77(Suppl 3): 1041-1044.

- Tsao K, Peter SD, Valusek PA, Spilde TL, Keckler SJ, et al. (2008) Management of pediatric acute appendicitis in the computed tomographic era. J Surg Res 147(2): 221-224.

- Luo C, Cheng K, Huang C, Lo HC, Wu SM, et al. (2016) Therapeutic effectiveness of percutaneous drainage and factors for performing an interval appendectomy in pediatric appendiceal abscess, BMC Surg 16(1): 72.

- McCann JW, Maroo S, Wales P (2008) Image guided drainage of multiple intraabdominal abscesses in children with perforated appendicitis: an alternative to laparotomy. Pediatr Radiol 38: 661.

© 2018 Tarik Zahouani. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)