- Submissions

Full Text

Strategies in Accounting and Management

The Effect of Capability and Usability on Consumer Preference Under Forced Adoption Condition

Tim Lu1 and Pei-Chun Chen2*

1Associate Professor, Department of Marketing and Logistics Management, Vanung University, Taiwan

2Assistant Professor, Department of Airline and Transport Service Management, Vanung University, Taiwan

*Corresponding author: Pei-Chun Chen, Assistant Professor, Department of Airline and Transport Service Management, Vanung University, Taiwan

Submission:November 09, 2021Published: November 22, 2021

ISSN:2770-6648Volume3 Issue1

Abstract

Forced adoption is becoming a common marketing tactic to ensure that the introduction of new products is successful, but little is known about how consumers evaluate the new products in this circumstance. Because new products are appealing to consumers by virtue of their more powerful functions or more friendly interfaces, capability and usability are the two key determinants of whether a new product will be adopted or purchased. Research based on construal-level theory indicates that consumers give more weight to capability before first use (distant future) and more weight to usability after first use (near future). However, forced adoption can trigger choice conflict, which causes preference reversals. According to a reasons-based approach, when consumers face a difficult decision they give more weight to the inferior attributes of a product, as these attributes provide a good reason to make a particular choice and thus resolve the difficulty. Therefore, usability is more important before a new product is first used, whereas capability is more important after first use. In this study, a structural model was constructed that contributes to the understanding of consumers’ behavioral intentions when they are forced to adopt a new product. We further explore the distinction between usage before and after adoption of the product. The study provides insight into the inconsistency of preferences as a function of temporal distance when consumers are forced to adopt a new product.

Keywords: Forced adoption; New products; Capability; Usability

Introduction

In many real-life situations, consumers are forced to adopt a new product if they continue

to seek the same objective or want to stick with the same provider. Forced adoption happens

because these new products are usually developed by the dominant firms for that product

line, firms that are more able than their competitors to invest large amounts of resources in

research and development (e.g., Microsoft). Consumers are most likely to adopt a new product

from the dominant firm if they are already using existing product from that firm or the new

product is very popular. Moreover, when a company decides to discontinue an old product,

consumers are also forced to adopt the new product. For example, to lower operating costs, a

company might shift to self-service procedures [1-3], as was the case when banks introduced

automated teller machines and airlines introduced self-service kiosks. Consumers are thus

compelled to change their usage behavior, perhaps unwillingly. This dilemma may induce

emotional discomfort and frustration, resulting in a negative attitude toward the product.

However, little is known about how consumers’ behavioral intentions are formed when they

are forced to adopt a new product. Is the new product’s popularity adversely affected? Clearly,

the issue is important practically as well as theoretically.

Consumers’ evaluations of the “capability” of a new product

(i.e., how well it works, how much it can do) and its “usability”

(i.e., ease of use) are the two most important determinants of

whether they adopt or purchase it [4-9]. This is because new

products tend to be more functional or user-friendly than the ones

they replace [5,10]. Although adding features can increase a new

product’s capability, they also can make it more difficult to use.

Consequently, consumers face a trade-off that makes their decisionmaking

process more complex and the decision itself more difficult.

Research further indicates that this complexity and difficulty

increases the irrationality or inconsistency of the choices [11-13]. A

number of marketing studies suggest that consumers’ evaluations

of new products vary as a function of temporal distance, that is,

how long a purchase or adoption is going to take place. According

to temporal construal-level theory [14,15], consumers favor more

abstract or desirable attributions (e.g., capability) in the distance

future, and they prefer more concrete or feasible attributions (e.g.,

usability) in the near future. Studies of new products have provided

results consistent with temporal construal-level theory [5,7,10,16].

Thus, there is a sound basis for hypothesizing that consumers’

preferences will change as a function of temporal distance when

they are forced to adopt a new product.

However, the most important characteristic of forced adoption

is the restriction of consumers’ freedom of choice, and this is the

main source of preference reversals. Limiting freedom of choice

induces psychological reactance, which leads to choose conflict

[11]. Basing on reason-based theory, consumers give more weight

to relatively trivial or inferior product characteristics when faced

with choice conflict, and the literature shows that selecting the

inferior option is served as a good reason to resolve the conflict

[17,18,11,12,19]. In other words, the findings predicted by

temporal construal-level theory may be reversed in the case of

forced adoption of new products. More specifically, we hypothesize

that usability is more attractive in the distant future (before the

new product is used), whereas capability is more attractive in the

near future (after the product is first used). The research model

explores the relationship between a new product’s major attributes

(capability and usability) and consumers’ behavioral intention to

use the product, as well as the factors that determine the product’s

capability and usability. We also examined how consumers weigh

their trade-off needs for capability and usability as a function of

temporal distance. All the hypotheses were tested in a field study

using survey data for assessing the usage of a new product. We

adopted it believing that it can increase our understanding of

consumers’ decision-making process with respect to a new product

and provide insights into the inconsistency of consumer preferences

at different temporal distances. Self-Service Technologies (SST) are

technological interfaces that enable customers to produce a service

without a service employee’s involvement. The need for airlines

to bring down their operating costs favors the use of self-service

technologies in services provided to passengers and at check-in,

specifically. From the company’s point-of-view, the use of SST can

drive up productivity and efficiency, reduce or avoid high labor

costs. In this study, we constructed an evaluation model that applies

when consumers are forced to adopt self-service baggage drop.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

The effects of capability and usability on new product evaluations as a function of temporal distance

A popular strategy for developing new products is to make

them more functional [6,20] or user-friendly than the products

they replace [5,10]. Both attributes play an important role in

determining whether consumers decide to purchase or adopt a

new product [21-23,5,6,24,7,10]. In general, researchers have

suggested that capability is more influential than usability on

consumers’ behavioral intentions [21,22,25]. This is because they

consider capability to be more important and more desirable than

usability [7,10].

A common way to enhance new products’ capability is to add

more features, but this often reduces ease of use [7,10]. This tradeoff

between capability and usability causes consumers’ decision

making to be more complex and difficult. Research indicates that

this difficulty creates conflict and increases the irrationality or

inconsistency of the purchasing decisions [11,12]. There is ample

empirical evidence that when consumers evaluate a new product,

they weigh capability and usability differently as a function of

temporal distance [26,5,7,10]. Most of these studies used temporal

construal-level theory [14,15] to explain the difference. According

to this theory, when consumers evaluate options for the distant

future, they give the most weight to capability. To the contrary, when

they evaluate options for the near future, they give more weight to

usability [5,7,10]. The conflict that underlies the inconsistency in

consumer preferences results in “feature fatigue,” which in turn

tends to lead consumers to choose overly complex products that do

not fully satisfy them when they use them [7]. These findings show

that the relative weights of capability and usability change because

of differences in how the products are evaluated at different

temporal distances.

How consumers weigh capability and usability in forced adoption conditions

Forced adoption means that consumers have no choice.

The perception of being restricted leads to conflict, emotional

discomfort, and frustration [11]. Thus, forced adoption can result

in a negative attitude toward the new product and the company

that makes it. These negative attitudes, in turn, lead to adverse

behavioral intentions reflected in switching to another provider or

negative word of mouth [1]. Although previous research suggests

that forced adoption indeed has negative effects, little is known

about how consumers evaluate the new product in this situation.

Consumer decision making under reason-based theory:

Previous research has advanced the notion that consumers’ choices

in conflict situations (e.g., forced adoption) can be better understood

if one considers the reasons for and against each alternative

[17,18]. Although the reasons suggested by researchers may not

always correspond to those that motivate actual decision makers,

it is generally agreed that a reasons-based analysis can help explain

these decisions [18,27], because focusing on reasons simulates

how consumers normally think and talk about their choices, and

it is a natural way to understand the conflict that underlies the

decision-making process [27]. Because forced adoption creates

psychological conflict, it is appropriate to use reasons-based theory

to explain consumers’ inconsistency in weighing capability and

usability at different temporal distances.

According to this reasons-based approach, decision makers

are more likely to choose alternatives that are perceived as most

justifiable to the others who will evaluate their choices, such

as supervisors, spouses, or groups to which the decision maker

belongs [28]. Generally, consumers give more weight to relative

common, superiority and important attributions such as utilitarian

and dominating attributes [17,29,30,19], because they are the most

readily justified for adoption purposes, cognitively available, and

diagnostic of the appropriate choice. These results suggest that the

focus of consumers’ decision-making process shifts from choosing

good options to choosing good reasons.

Consumer preferences when forced to adopt a new product:

the effect of temporal distance: According to the reasons-based

approach, people generally give more weight to the most important

attributes of the product. However, researchers further indicate that

consumers may give more weight to the less important attributes

when they encounter with choice difficulty [17,18,11,12,19]. The

relative weight given to the superiority and inferiority attributes

can change; the superiority attributes provide a more justifiable

basis for the decision in common events, but the inferior attributes

is served as good reasons to resolve the difficulty. When consumers

are forced to adopt a new product, their decision becomes much

more complex and difficult. The conflict becomes apparent when

people think they have chance to reject a new product, as in the

distant future. However, if the adoption is a fact (as in the near

future) or the product is “crammed down the consumer’s throat”,

all the consumers can do is accept the new reality, which then

eliminates the conflict. Thus, we hypothesized for this study that

when consumers are forced to adopt a new product, they will

consider secondary attributes in their evaluations of the product

before they adopt it (placing more weight on its usability), but they

will give more consideration to primary attributes after they have

used the product (assigning more weight to its capability).

H1: The positive relationship between capability and behavioral

intention is stronger after consumers are forced to adopt a new

product than before they are forced to adopt it.

H2: The positive relationship between usability and behavioral

intention is stronger before consumers are forced to adopt a new

product than after they are forced to adopt it.

The relationship between capability and usability

Studies on marketing and information management show a

high correlation between capability and usability. Researchers

have suggested that consumers are likely to use the quality of

lower level/concrete attributes to infer the quality of higher level/

abstract attributes [31]. Because previous studies indicate that

capability is considered to be a more important attribute than

usability [7,10], it has been assumed that the perception of usability

partly determines the perception of capability. There is ample

evidence from the information management literature confirming

this assumption [26,21,33]. These researchers used the Theory

Of Reasoned Action (TRA) to expand the Technology Acceptance

Model (TAM) [22], thereby being the first to postulate a causal

relationship between perceived usability and perceived capability.

The relationship arises because improvement in a products’ ease of

use instrumentally contributes to increasing its performance. The

effort saved by increased ease of use can be redeployed, enabling

users to accomplish more tasks with the same effort. Thus, they

consider the product more useful. Yousafzai et al. [32] present a

rigorous meta-analytic review of 145 papers published on the TAM,

concluding that there is a statistically significant effect of usability

on capability. However, most of the literature has focused on

consumer perceptions before the product is first used. We predict

that this relationship will hold both before and after first use.

H3: Consumer’s perceptions of product usability are positively

associated with their perceptions of product capability both before

and after the product is first used.

Determinants of capability and usability

Choice difficulty resulting from forced adoption of a new

product can make individuals feel bushed and helpless. Thus,

people crave other peoples’ opinions and any external assistance

they can get to make the difficult choice. According to the literature,

the need to refer to others’ opinion is virtually a norm, as is the

demand for extraneous help. Derived from the TRA, a subjective

norm (also called a social norm) is “the person’s perception that

most people who are important to him think he should or should

not perform the behavior in question” [34]. Because subjective

norms are considered to offer an important explanation of

consumers’ acceptance behavior [26,35], we consider it necessary

to include this construct in our research model on forced adoption.

[26] suggested that subjective norms are formed on the basis of

internalization, a kind of information influence that occurs when

individuals accept information as evidence of reality. Internalization

may increase the effect of the subjective norm on perceived

capability [33], because the opinions of important referents could

influence a person’s evaluation of the utility of a product. Hence, the suggestion of a superior, peer, or friend that a new product is

functional could affect the individual’s perception of that capability,

especially if the recipient of the suggestion is in a forced adoption

situation. Moreover, we hypothesize that the relationship between

the subjective norm and capability should hold both before and

after the consumer first uses the product.

H4: Consumers’ perceptions of a subjective norm have a positive

effect on their perceptions of the product’s capability both before

and after first using it.

The second important exogenous factor involves facilitating

conditions, defined as objective factors in the environment

that observers agree make an act easy to accomplish [7]. Most

researchers who consider such factors important explain consumer

behavior in an information system context. They find that this

definition captures two different constructs: perceived resources

[36] and perceived behavioral control [37]. In other words,

facilitating conditions represent the extent to which individuals

believe that they have the external assistance needed to perform

a behavior.

The more external assistance that comes from individuals

or organizations, the more willing the individual will be to

perform the activity. Most relevant studies have linked facilitating

conditions to behavioral intentions, but other studies show that

facilitating conditions do not significantly influence intentions [38].

Previous studies further suggest that facilitating conditions affect

behavioral intentions through perceived ease of use and usefulness

[39]. Specifically, facilitating conditions predict intention only if

perceived usability is not present in the model [37]; Ali et al. We can

conclude from these research results that usability fully mediates

the effect of facilitating conditions on behavioral intentions. Thus,

we hypothesize that the more facilitating conditions are available

to consumers of a new product adoption, the more usability they

perceive for the product. Moreover, whereas previous research

mostly has explored this relationship only before first use, we

predict that it will hold both before and after first use when

consumers are faced with forced adoption.

H5: Consumers’ perceptions of facilitating conditions have a

positive effect on their perceptions of product usability, both before

and after first use of the product.

Methodology

Study context and sample

Data were collected through a questionnaire conducted with customers who are members of the airline’s frequent flyer program. User reactions to self-service baggage drop were gathered at two points in time during a six month: airline check in at the counter by the ground attendant (T1) and after six months of actual usage (T2). Thus, T1 represented before first time use, and T2 represented after first time use. There were 204 valid questionnaires collected at T1 and 216 at T2. Among the respondents at T1, 146(71.57%) passengers were female, 96 passengers were between the ages of 46-55(47.06%). Among the respondents at T2, 159(73.61%) passengers were female, 107 passengers were between the ages of 46-55(49.53%).

Measures

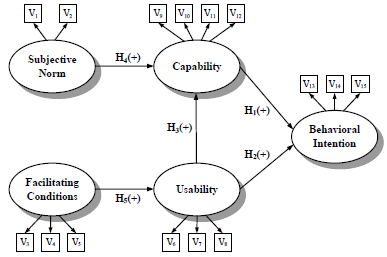

The 15 questionnaire items were adapted from prior research, with wording changes to make them appropriate for the airline self-service baggage drop context. Two items referred to the subjective norm, three to facilitating conditions, three to usability, four to capability, and three to behavioral intention (see Appendix). All items were responded to on five-point Likert scales, with the alternatives ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The associations of the five constructs, their indicators (the items), and the research hypotheses are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Measurement model and research hypotheses.

Note: “+” refers to the positive effect.

Results

Measurement model

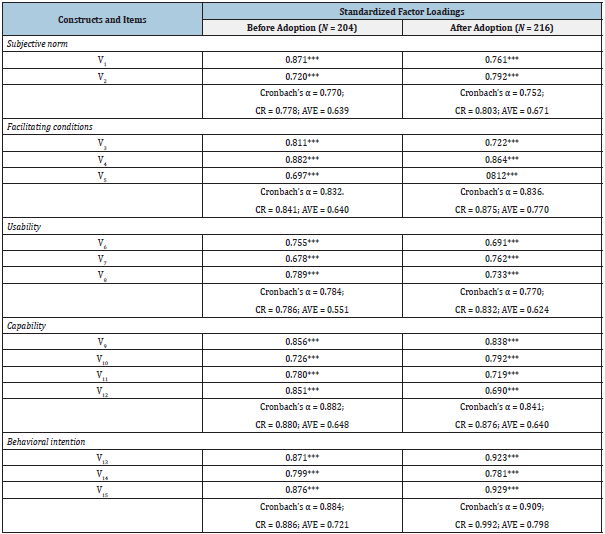

We performed two confirmatory factor analyses, one for preadoption and one for post-adoption. Both models exhibited a good fit to the data: pre-adoption: χ2 (80) =142.320, Goodness-of-Fit Index [GFI]=0.917, Comparative Fit Index [CFI]=0.968, Normed Fit Index [NFI]=0.930, and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation [RMSEA]=0.062; post-adoption: χ2 (80) =139.797, GFI=0.925, CFI=0.971, NFI=0.936, and RMSEA=0.059. Table 1 provides the detailed results of the two analyses. For each construct, Cronbach’s α exceeded the standard for acceptance of 0.7, the composite reliability exceeded the standard of 0.6, and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) exceeded the standard of 0.5. Convergent validity was also supported for each construct of both models in that all the factor loadings were highly significant (p<0.001) and all the standardized factor loadings were greater than 0.5.

Table 1: Results of the confirmatory factor analysis.

Note: CR = Composite Reliability; AVE = Average Variance Extracted

We began the assessment of discriminant validity by computing the chi-square difference statistic for the unconstrained models (pre-adoption: χ2 (80) =142.320; post-adoption: χ2 (80) =139.797) and the constrained models. The constrained models are estimated by fixing the correlation between two constructs of interest at 1. The results show that for each pair of constructs both before and after adoption, the chi-square value of the unconstructed model is significantly lower than all constrained model. Thus, each constructs are viewed as distinct factors, and we can conclude that discriminant validity was supported for each construct of both preadoption model and post-adoption model.

Structural models

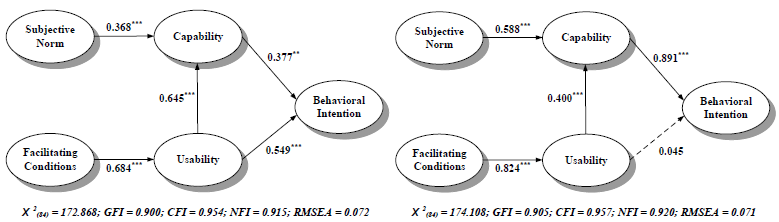

To test the hypotheses, we configured two structural models separately. The first model consisted of the pre-adoption samples (N=204) and the second consisted of the post-adoption samples (N=216). Figure 2 display the results for the two models. Both had acceptable fit to the data with respect to complexity and sample size: pre-adoption: χ2 (84) =172.868, GFI=0.900, CFI=0.954, NFI=0.915, and RMSEA=0.072; post- adoption: χ2 (84) =174.108, GFI=0.905, CFI=0.957, NFI=0.920, and RMSEA=0.071. The path coefficient estimates show that capability had a positive effect on behavioral intentions both before and after adoption, whereas usability had a positive effect on behavioral intentions only before adoption. These results provide partial support for H1 and H2. The R2 for behavioral intention was 0.858 before adoption and 0.789 after adoption, indicating that capability and usability account for 85.8% and 78.9% of the variance in behavioral intention respectively. Results for the path leading to product capability show that both usability and subjective norm were positively associated with capability, both before and after adoption. Thus, H3 and H4 are supported. From the R2 estimates of capability (pre-adoption: 0.808; postadoption: 0.795) we can conclude that the usability and subjective norm respectively accounted for 80.8% and 79.5% of the variance of capability. The results also indicate a positive effect of facilitating condition on usability both pre-adoption and post-adoption. Thus, H5 is supported. The R2 values for usability (pre-adoption: 0.679; post-adoption: 0.468) reveal that facilitation condition is a key determinant of usability.

Figure 2: Results of the structural model analysis.

Note: *p <0.01; ***p <0.001.

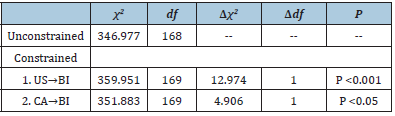

Multigroup analysis

Hypotheses 1 and 2 predicted that the associations of capability and usability with behavioral intentions will be different before and after consumers are forced to adopt a new product. To test these hypotheses, we conducted a multigroup analysis with the data from both periods. We then tested the equality of both path coefficients across the two groups by using a chi-square difference test to compare a model with a free path coefficient (unconstrained model) to a model with a specific path set to be equal for the two groups (constrained model). Table 2 displays the results of this analysis. For the unconstrained model, χ2 (168) =346.977. When we constrained the path coefficient of capability → behavioral intentions equally across the two groups, χ2 (169) =359.951. As for the difference between the models, Δχ2 (1) =12.974 (p<0.001), suggesting that the effect of capability on behavioral intentions was not equal at T1 and T2. Moreover, the parameter estimates shown in Figure 2 indicate that the capability → behavioral intention path had a higher value after adoption (b=0.891, p<0.001) than before adoption (b=0.377, p<0.01). Thus, H1 is supported; the relationship between capability and behavioral intention is stronger after consumers are forced to adopt a new product than before they are forced to adopt it. The same analysis process was conducted to test the path from usability to behavioral intentions. Here, we found Δχ2 (1) =4.906 (p<0.05) between the unconstrained and the constrained models. Furthermore, the parameter estimates in Figure 2 reveal that the usability → behavioral path was significant before adoption (b=0.549, p<0.001) but nonsignificant after adoption (b=0.045, p>0.1). Hence, H2 is supported; the effect of usability on behavioral intentions is stronger before consumers are forced to adopt a new product than after they are forced to adopt it.

Table 2: The multigroup analysis of the structural model.

Note: US = Usability; CA = Capability; BI = Behavioral Intention

Discussion

Theoretical implications

The major theoretical contribution of this study is to provide

a better understanding of how consumers switch their preference

for a new product as a function of temporal distance when they are

forced to adopt it. We concluded that the changes in the relative

weights consumers assign to the capability and usability of new

product are based on the reasons-based theory. Our results show

that before participants were forced to adopt a new SST, their usage

intentions were guided more by their evaluations of the SST’s

usability than its capability, whereas they gave more weight to

the SST’s capability after they actually started using it. Our results

differ from those of previous relevant studies because forced

adoption leads to psychological conflict and emotional discomfort.

As predicted by the reasons-based theoretical approach, when

people are in a state of conflict, they often pay paramount attention

to product attributes that they normally would consider of less

importance, such as how easy the product is to use. In such a forced

situation, the product’s usability becomes a good reason to justify

the consumer’s adoption of the new product. In other words, those attributes are preferred that offer a reason for the decision and

help reduce the consumer’s feelings of conflict and discomfort.

However, after the product is purchased and becomes a part of

the consumer’s life, the conflict is reduced, and the focus shifts to

the more important attributes of the product having to do with its

capability. At this stage, this more important characteristic is the

reason or justification the consumer can cite for continuing to use

the product.

Our results also have implications for temporal construallevel

theory, as the conflict consumers experience when forced to

adopt a new product may cause them to weight capability (i.e., the

desirability per se of the product’s main features) and feasibility

(i.e., usability) differently in the distant and the near future. When

a purchase or a decision raises conflict, consumers favor a more

feasible (easy to use) option in the distant future and a more

inherently desirable option in the near future. We further indicated

a positive relationship between perceived product usability and

perceived product capability both before and after initial use.

The easier to use that consumer considered the new SST to be,

the more functional they found it to be. This relationship implies

that feasibility might enhance the inherent desirability of a new

product that is forced on the consumer. Especially when conflict

and discomfort are aroused, a product’s secondary attributes could

increase the attention paid to its primary attributes.

Consistent with our last two hypotheses, the results suggest that

the presence of a subjective norm has a positive effect on perceived

product capability, and facilitating conditions have a positive effect

on perceived product usability. Our findings imply that psychological

conflict resulting from the forced adoption of a product leads

consumers to rely much more on important referents’ opinions to

evaluate product capability. They also imply that consumers rely on

external assistance to learn how to use a new product. Assimilation

of a social norm can encourage consumers encountering a forced

adoption situation to conform to the expectations of others.

Moreover, the suggestions of these others are likely to be treated as

treated as an information as evidence of products capability. With

respect to facilitating conditions, when a new product is supplied

with an additional function, consumers are burdened with one

more thing to learn and one more thing to search through when

looking for what they want. Because the new function thus is likely

to reduce the product’s ease of use, external assistance can make

it easier for consumers to learn about problems with the new

product and further enhance their awareness of its capabilities.

Finally, our findings show a link between facilitating conditions and

product usability both before and after forced adoption. This result

suggests that because consumers’ adoption of the new product is

not voluntary or based on careful consideration of the product’s

attributes, learning about how the new product is used can also be

forced. Even after consumers have started using the product, they

still need external assistance to learn how to use it most efficiently.

Managerial implications

Our research has several managerial implications for marketers

who want to promote new products. With forced adoption,

consumers’ use intentions are associated with product usability in

the distant future (before initial use), whereas product capability

is relatively important to intention in the near future (after initial

use). Thus, for a company that dominates the market for its product

line, the development of a new product is likely to be focused not

only on continually adding new functions to the product, but also on

resolving consumers’ problems with using the product. In the initial

stages of promoting a new product, marketers should advertise it

by stressing its simplicity and user-friendliness compared to the old

product. The capability of the product should be emphasized after

consumers are attracted by the product’s usability. Generally, this is

the point at which consumers are about to decide whether or not to

purchase the new product. In terms of construal-level theory, it is

important to keep in mind that distance can be both temporal and

spatial. Companies may need to employ different advertisements

in different channels. They should accentuate product usability

in advertisements that will be accessed far removed in space and

time from the potential purchase, such as in magazines, on TV, or

on the internet. On the other hand, ads should stress the product’s

capability if they are to be accessed close to where and when the

consumer will make the potential use.

Our findings suggest that if a firm is beginning to promote a

new product featuring major improvements in user-friendliness, it

should completely withdraw the old product as soon as the new

product is introduced. The reason is that such total replacement

creates a forced adoption situation, which we found leads

consumers to focus on the new product’s usability. In other words,

the improvement in product usability becomes a good reason for

consumers to purchase the new product. On the other hand, when

the main improvements in the new product concern its capability,

the company need not withdraw the old product when the new

one is introduced. This is because that, consistent with the findings

of relative literature [40,7,10], consumers are more concerned

about the product’s capability when they do not encounter forced

adoption. The existence of the old product actually highlighted the

advantages of the new product with respect to capability. In short,

companies’ new product marketing strategies should be based on

what characteristics of the new product show the most improvement

over the old product. Finally, creating a positive atmosphere

around the inevitability of the new product can soften consumers’

experience of compulsion. This softer approach might help to

reduce the negative repercussions of the compulsion by creating a

social norm around using the new product. Our results suggest that

this specific social norm can also help to make perceptions of the

product’s capability more positive and thus encourage favorable

behavioral intentions. For example, a marketer might stress how

the product protects the environment, an important issue for

humanity, by using recyclable products for its manufacture [41]. This strategy could improve consumers’ perceptions of product’s

capability and hence increase their willingness to buy it [41].

Appendix-Questionnaire Items

Subjective norm

V1: My family/friends think I should use self-service baggage

drop.

V2: Other passengers think self-service baggage drop is

wonderful.

Facilitating conditions

V3: This airline has provided the resources necessary to use

self-service baggage drop.

V4: In general, This airline has supported the use of self-service

baggage drop.

V5: A specific person (or team) is available for assistance with

self-service baggage drop using difficulties.

Usability

V6: The instructions for self-service baggage drop are clear and

understandable.

V7: It would be easy for me to become skilled at using selfservice

baggage drop.

V8: Learning to use self-service baggage drop will be easy for

me.

Capability

V9: I would find self-service baggage drop useful.

V10: Using self-service baggage drop would enable me to

accomplish check in process more quickly.

V11: Using self-service baggage drop would increase the baggage

check-in more smoothly.

V12: Using self-service baggage drop would improve the

accuracy of baggage check-in.

Behavioral intentions

V13: I intend to use self-service baggage drop as often as needed.

V14: I prefer to use self-service baggage drop.

V15: To the extent possible, I would use self-service baggage

drop frequently.

References

- Reinders MJ, Dabholkar PA, Frambach RT (2008) Consequences of forcing consumers to use technology-based self-service. Journal of Service Research 11(2): 107-123.

- Cserdi Z, Kenesei Z (2020) Attitudes to forced adoption of new technologies in public transportation services. Research in Transportation Business and Management, pp. 100611.

- Feng W, Tu R, Lu T, Zhou Z (2018) Understanding forced adoption of self-service technology: The impacts of users’ psychological reactance. Behaviour & Information Technology 38(3): 820-832.

- Nilsson E, Pers J, Grubbström L (2021) Self-service technology in casual dining restaurants. Services Marketing Quarterly 42(1-2): 57-73.

- McLaughlin J, Skinner D (2000) Developing usability and utility: A comparative study of the users of new it. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 12(3): 413-423.

- Mukherjee A, Hoyer WD (2001) The effect of novel attributes on product evaluation. Journal of Consumer Research 28(3): 462-472.

- Thompson DV, Hamilton RW, Rust RT (2005) Feature fatigue: When product capabilities become too much of a good thing. Journal of Marketing Research 42(4): 431-442.

- Robertson N, McDonald H, Leckie C, McQuilken L (2016) Examining customer evaluations across different self-service technologies. Journal of Services Marketing 30(1): 88-102.

- Ratten V (2014) Behavioral intentions to adopt technological innovations: The role of trust, innovation and performance. International Journal of Enterprise Information Systems 10(3): 1-13.

- Ziamou PL, Veryzer EW (2005) The influence of temporal distance in consumer preferences for technology-based innovations. Journal of Product Innovation Management 22(4): 336-346.

- Dhar R, Simonson I (2003) The effect of forced choice on choice. Journal of Marketing Research 40(2): 146-160.

- Novemshy N, Dhar R, Schwarz N, Simonson I (2007) Preference fluency in choice. Journal of Marketing Research 44(3): 347-356.

- Xuea P, Joa W, Bonn MA (2020) Online hotel booking decisions based on price complexity, alternative attractiveness, and confusion. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 45: 162-171.

- Liberman N, Trope Y (1998) The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distance future decisions: A test of temporal construal theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75(1): 5-18.

- Trop Y, Liberman N (2003) Temporal construal. Psychological Review 110(3): 403-421.

- Dhar R, Kim EY (2007) Seeing the forest or the trees: Implications of construal level theory for consumer choice. Journal of Consumer Psychology 17(2): 96-100.

- Brown CL, Carpenter GS (2000) Why is the trivial important? a reasons-based account for the effects of trivial attributes on choice. Journal of Consumer Research 26(4): 372-385.

- Chernev A (2005) Context effects without a context: Attribute balance as a reason for choice. Journal of Consumer Research 32(2): 213-223.

- Simonson I, Nowlis SM (2000) The role of explanations and need for uniqueness in consumer decision making: unconventional choice based on reasons. Journal of Consumer Research 27(1): 49-68.

- Nowlis SM, Simonson I (1996) The effect of new product features on brand choice. Journal of Marketing Research 33(1): 36-46.

- Davis FD (1989) Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly 13(3): 319-340.

- Davis FD, Bagozzi RP, Warshaw PR (1989) User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of theoretical models. Management Science 35(8): 982-1003.

- Kim JH, Park JW (2019) The effect of airport self-service characteristics on passengers technology acceptance and behavioral intention. Journal of Distribution Science 17(5): 29-37.

- Rafique H, Almagrabi AO, Shamim A, Fozia A, Bashir AK (2020) Investigating the acceptance of mobile library applications with an extended Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). Computers & Education 145: 103732.

- Asmy M, Mohd B, Thaker T, Bin A, Pitchay A, et al. (2019) Factors influencing consumers’ adoption of Islamic mobile banking services in Malaysia. Journal of Islamic Marketing 10(4): 1037-1056.

- Karahanna E, Straub DW, Chervany NL (1999) Information technology adoption across time: a cross-sectional comparison of pre-adoption and post-adoption beliefs. MIS Quarterly 23(2): 183-213.

- Shafir E, Simonson I, Tversky A (1993) Reason-based choice. Cognition 49(1-2): 11-36.

- Simonson I (1989) Choice based on reasons: The case of attraction and compromise effects. Journal of Consumer Research 16(2): 158-174.

- Chernev A (2001) The impact of common features on consumer preferences: a case of confirmatory reasoning. Journal of Consumer Research 27(4): 475-488.

- Okada EM (2005) Justification effects on consumer choice of hedonic and utilitarian goods. Journal of Marketing Research 42(1): 43-53.

- Zeithaml VA (1988) Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing 52(3): 2-22.

- Yousafzai SY, Foxall GR, Pallister JG (2007) Technology acceptance: A meta-analysis of the TAM: part 1. Journal of Modelling in Management 2(3): 251-280.

- Venkatesh V, Davis FD (2000) A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Management Science 46(2): 186-204.

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I (1975) Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, Addison-Wesley, Massachusetts, USA.

- Venkatesh V, Morris MG (2000) Why don’t men ever stop to ask for direction? gender, social influence, and their role in technology acceptance and usage behavior. MIS Quarterly 24(1): 115-139.

- Mathieson K, Peacock E, Chin WW (2001) Extending the technology acceptance model: The influence of perceived user resources. Database for Advances in Information Systems 32(3): 86-112.

- Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, Davis FD (2003) User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly 27(3): 425-478.

- Okumusa B, Alib F, Bilgihanc A, Ozturk AB (2018) Psychological factors influencing customers acceptance of smartphone diet apps when ordering food at restaurants. International Journal of Hospitality Management 72: 67-77.

- Pillai R, Sivathanu B, Dwivedi Y (2020) Shopping intention at AI-Powered Automated Retail Stores (AIPARS). Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 57: 102207.

- Castano R, Sujan M, Kacker M, Sujan H (2008) Managing consumer uncertainty in the adoption of new products: Temporal distance and mental simulation. Journal of Marketing Research 45(3): 320-336.

- Venkatesh V (2000) Determinants of perceived ease of use: Integrating control, intrinsic motivation, and emotion into the technology acceptance model. Information Systems Research 11(4): 342-365.

© 2021 Pei-Chun Chen. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)