- Submissions

Full Text

Strategies in Accounting and Management

Incorporating Inter-Firm Social Capital into International Business Theory

Shaun Cheah1 and Cameron Gordon2*

1Lecturer, Faculty of Art and Design, University of Canberra, Australia

2Associate Professor, Research School of Management, Australian National University, Australia

*Corresponding author: Cameron Gordon, Associate Professor, Research School of Management, Australian National University, Australia

Submission: July 01, 2020Published: April 6, 2021

ISSN:2770-6648Volume2 Issue3

Abstract

This paper explores and provides an understanding of how B-to-B relationships can be better understood by incorporating a Social Capital (SC) framework. It argues that SC dimensions (i.e., relational, cognitive and structural), underpin alliances that are salient to International Business (IB). A synthesis of the literature on B-to-B SC and loyalty into a single, process-based framework is established, together with institutional texture insights for firms to harness and develop for success. The central argument is that investments in relationship building not only enhance B-to-B loyalty but over time fashion the nature and depth of the alliance for the international firm. The paper adds to the literature on international B-to-B collaborations whilst having the potential in providing managerially relevant (“actionable”) results in ‘how’ and in ‘what way’ B-to-B SC can be harnessed in the 21st century IB system.

Keywords: Social capital; International business; Inter firm (B-to-B) collaborations; Loyalty

Introduction

International Business (IB) research is increasingly focusing on intra and inter-firm

coordination with Mathews [1], Peng [2], Buckley [3] and Dunning [4] calling for closer

specification of how institutions facilitate and underpin cross-border trade and investment.

This international system of production that emerged in the late 20th century is becoming

increasingly institutionally based, rather than purely market transaction focused. The

emerging business environment is well captured in the term global factory, where changes

in managerial style and innovations are essential to warrant success in a highly competitive

global economy. Here, the evolution of the global factory requires managers to have a greater

understanding whilst acting as coordinators across the system of internationally interconnected

firms Buckley [3]. Institutions matter, but how? The point of departure taken in

this article is to expand on the current understanding of IB institutions by incorporating

the formation of Social Capital (SC) into the specific and important challenge of Businessto-

Business (B-to-B) institution building. It will be argued that the accretion of SC through

relationship building (and nurturing) is central to the formation of networks for and between

firms. In a sense an SC framework can better accommodate B-to-B institutions, relationships

and transactions than an institutional perspective alone.

The outline of this article is as follows: The literature on B-to-B and SC relationships will

be reviewed focusing on how SC allows businesses to harness and develop for success. A

conceptual model is then proposed which argues that SC influences loyalty intentions through

the network of relationships (structural dimension of SC); quality of those relations (relational

dimension of SC); and the shared beliefs of the relationship partners (cognitive dimension

of SC). Particularly important is SC’s unique feature associated to other forms of capital as

SC is inherently bound with the organization and development of the business Walker [5],

Nahapiet [6], Moran [7]. The paper ends with a proposed research agenda that could bring

together a wide range of measures that have been applied in marketing and IB literature and

answers the call for closer qualitative examination of B-to-B SC relationships.

B-To-B in the Current International Business Marketplace

Inter-firm (b-to-b) strategy, institutions, and transaction costs in international business: The traditional view

What drives firm performance and strategy in International

Business (IB)? What governs the success and failure of firms

(and B-to-B relationships) around the world? Traditionally, the IB

literature outlines two perspectives; an industry-based view, which

argues that “conditions within an industry, determine firm strategy

and performance” Porter [8] and a resource-based view, which

suggests that it is “firm-specific differences” that drive strategy and

performance Barney [9]. These observations are principally in the

field of strategic management. Given how the ‘new institutionalism’

has progressed in social sciences in past years North [10], Oliver

[11], Williamson [12] and Hall [13], the notion that ‘institutions

matter’ is hardly novel. What is intriguing though is ‘how’ and it

‘what way’ it matters. This is reinforced by Narula [14] who posit

that the “process of globalization requires us to develop, modify

and improve the available theoretical and conceptual frameworks

that the IB literature provides us”.

There is already much study of the institutional responses

of firms to these changes in the global marketplace. In particular

the use of strategic alliances, defined by Gulati [15], as “voluntary

arrangements between firms involving exchange, sharing, or codevelopment

of products, technologies, or services...occurring as a

result of a wide range of motives and goals, [and taking]...a variety

of forms...across vertical and horizontal boundaries”, are now a

universal phenomenon and their propagation has led to a rising

stream of research by strategy and organizational scholars who

have examined the partnership processes, causes and outcomes,

mostly at the dyadic level Auster [16]. As is well-known in the

literature, B-to-B partnerships are set across a continuum, ranging

from minimal inter-firm connections except that which is explicitly

contracted for on a transaction-by-transaction basis (for example, a

foreign export agent that connects an offshore firm with domestic

clients) all the way to deep, equity-based firm entwinement (such

as wholly owned subsidiaries or jointly owned strategic alliances

and partnerships) Peng [2]. Whatever such collaborations entail,

they are usually seen by both academics and businesspeople in

transactional terms, positing that an alliance (or any other related

inter-firm coordination mechanism) is a matter of benefits versus

costs. If net benefits become negative for too long the alliance will

suffer or even fall apart.

However, there are many examples where one-party benefits

much more from a relationship than the other, yet it still carries

on. A case in point would be in the Apple and Foxconn relationship.

The Apple-Foxconn business partnership was outlined by Chan

[17] as being ‘highly unequal’. The ‘competitive advantage’

that Apple has lies in the combination of corporate leadership,

technological innovation, design and marketing Lashinsky [18]

whilst its financial success lies primarily from the ‘hard-nosed’

management of production of its suppliers who are mainly based in

Asia. As a result, Apple’s volume, coupled with ‘ruthless’ business

dealings allow them to ‘take advantage’ of its suppliers Satariano

[19]. In this instance Foxconn accommodated Apple’s ‘squeeze’

while continuing to reduce labor expenditures, including cuts

in wages (mainly overtime premiums) and benefits Gulati [15].

This collaboration is mostly financial, based upon transactional

cost economics, and demand responsive. But the value of the

relationship and its corresponding repercussions to its business

partners (i.e., Foxconn), though secondary, does seem to have

some independent value, enough so that even with rather blatant

inequality it has proven to be resilient.

Certainly, the economic motivations for most business alliances

are paramount. Firms don’t form alliances as symbolic social

affirmations but base these alliances on strategic complementarities

that are offered to each other. Yet it could be that the conditions

of mutual economic advantage are necessary but not sufficient for

inter-firm (B-to-B) alliance formation. Gulati [15] had postulated

that firms entering alliances face considerable ‘moral hazard’ issues

because of partner behaviour unpredictability and the likely costs

from opportunistic behaviour. This is the case with the Apple-

Foxconn alliance. Here Apple, is behaving opportunistically and

although Apple’s partnership with Foxconn is ‘somewhat efficient’,

the literature suggests that having a better relationship can enhance

this efficiency Chan [17], Lashinsky [18].

The concept of ‘somewhat efficient’ is an important one.

Hagedoorn [20] argued that the selection of partners representing

profit maximizing entities is optimal only in a static environment.

Kay [21] however explains that “it is necessary to engage in networks

with certain firms not because they trust their partners, but in order

to trust their partners”. Thus, transaction cost economics and related

theories (such as internalization theory) cannot always be utilized

as a complete explanation for international activities, especially in

a dynamic setting. This is more so as human characteristics such

as trust and bonding are not fully captured. This is where the SC

concept can be useful both in theoretical understanding and in

business practice.

The social capital concept and business

The literature reveals over 19 definitions of social capital

Knoke [22], Coleman [23], Burt [24], Adler [25], Moran [7], Krause

[26] and Eklinder [27] with the differences relating mainly to

whether social capital (SC) is analyzed within an organization, in

partnerships amongst organizations and their external actors, or

both. Overall, the consensus is that ‘relationships’, whatever their

specific form (e.g. strategic alliance) are an essential part and a

critical dimension of SC, with SC itself existing as an independent

intangible asset arising from such relationships. SC can be said to

be the goodwill established to facilitate action Adler [25] while it

is the interacting members who facilitates the reproduction of this

social asset Bourdieu [28], Portes [29], Putnam [30] and Lin [31].

Therefore, SC is an important resource because individuals work

together more efficiently when they know one another, understand

one another, as well as trust and identify with one another. In

this sense SC is a supplement to transaction costs management

in business setting, both because it lowers costs (genuine trust is lower cost than enforcement without trust) and by creating an

‘asset’ that has independent value that can weather unforeseen

events better.

SC derived from business relationships has been shown to

impact bottom line results Cohen [32], Jones [33] and as such an

understanding of SC’s nature is essential as a key element of a firm’s

competitive advantage. Further, a primary factor of successful

relationship and SC building is a dedication to work towards

mutually beneficial relationships. Therefore, the development of

B-to-B SC is affected by the dynamics of actors between businesses,

and thus can limit or enhance any advantages that that SC renders.

In the best case, SC can create a virtuous circle whereby solid trust

builds SC which deepens trust which further enhances SC. SC is

also differentiated by sociologists and organizational theorists into

various dimensions: structural SC - the number of ties between

relationship partners Burt [34]; relational SC – the strength

of relationship or the quality of an actor’s personal relations

Granovetter [35]; and cognitive SC - the shared beliefs of the

relationship partners Nahapiet [6].

Structural SC includes social interaction and is embedded in

components such as social dimension ties, network connection

consequences and strength, and network density. In essence, it is

fundamentally the extent to which businesses are connected. The

relational dimension of SC is the quality of B-to-B relationships

and stems from relationship-reliant consequences. It essentially

describes the relationship strength developed by network members

through a history of interactions Nahapiet [6]. The cognitive

dimensions of SC are characteristics of the environment, embedded

in person-related intangible skills where businesses work together

for the common good. It is the extent to which their social networks

share a common goal in the areas of beliefs, interests, values,

language, norms of behavior, and systems of meaning Nahapiet [6].

Cognitive SC is also rooted in the study of communal relationships

and sociology where common goals assist in facilitating collective

behaviors. In summary, the literature suggests that the relationship

strength and shared beliefs typically result in higher SC. In a

business setting this may result in improved performance and

competitive advantage, though obviously these outcomes depend

on many other factors. Moreover, research has posited positive

effects relating to commitment, closeness of relationship (which

is relational SC proxies) on loyalty-related outcomes Barnes [36],

Bansal [37]. It is based upon the above that the three SC dimensions

will be used as a key construct to reflect how they contribute to the

study of B-to-B SC relationships in the IB context.

Social capital and inter-firm (B-to-B) relationship

Several studies have explored the importance and effectiveness

of social embeddedness on the formation of inter-firm (B-to-B)

cooperation. For instance, studies have used the social network of

prior B-to-B alliances to show that those with more prior alliances

were more likely to enter into new alliances. They did so also

with greater frequency Kogut [38], Gulati [39]. Similar findings

have also been reported for the influence of firm alliance include

alliance networks among bio-technology firms, semi-conductor firms and their patent citation networks Podolny [40], and those

of top management teams of semi-conductor firms Eisenhart [41].

Each network highlights a different underlying social process that

enables central firms to enter alliances more frequently.

As far as B-to-B alliances breaking down, the literature shows

that B-to-B partnerships with a prior history of ties were less likely

to terminate their collaboration Kogut [42]. In another important

set of studies, Levinthal [43], Seabright [44] determined that

the duration of exchange relationships is not only influenced by

changes that occur in task conditions, but there may be ‘dyadic

attachments’ between firms that lead to the persistence of such ties.

Marketing and strategy scholars have also resorted to extensive

studies administered to the individual managers responsible

for the alliance from each partner Heide [45], Parkhe [46]. Such

approaches enable the collection of a host of measures, subjective

and objective, on which the B-to-B alliances can be assessed.

The theoretical underpinning of these findings goes as follows.

Firms are embedded in a social structure of dependence that

can possibly alter the power dynamics in a potential alliance.

Partnering firms are also likely to have greater confidence (and

trust) in each other, whilst the network creates a natural deterrent

for bad behavior that will damage reputation. Trust enables

greater exchange of information, promotes ease of interaction and

facilitates a flexible orientation on the part of each partner. These

can create enabling conditions under which the success of an

alliance is much more likely Gulati [47]. Such social structures can

limit opportunistic behaviors (as with earlier noted Apple-Foxconn

alliance) leaving firms to be more willing to make non-recoverable

investments, which in turn enhance alliance performance. Surveybased

evidence also further confirms that both interpersonal and

B-to-B level trust can be influential in the performance of exchange

relationships Zaheer [48]. Also, while there have been several

efforts to explore differences in ‘embedded’ ties between firms,

studies don’t directly assess whether embedded ties perform any

better than other ties. Also, while embedded ties differ from other

ties, we have less understanding of the extent to which alliances,

with embedded ties, actually perform better or worse than other

alliances and why. Research of B-to-B relationships have primarily

focused on the implications of embeddedness, yet the social and

economic contexts in which firms are embedded on their choice of

alliances remains underexplored. There may also be implications

from the embeddedness of firms in other types of social networks

that could influence the design of alliances, but this has yet to be

examined. A key consideration in operationalizing all this research

would be to focus directly on the ways social networks (through

social capital dimensions) play a role and whether the extent of

embeddedness in social networks is an important factor. While

there have been advances in assessing these B-to-B alliances, few

of these efforts have considered the impact of social networks

(and relationships), specifically through SC dimensions Medlin

[49]. As such, there has been considerable interest in uncovering

the processes that underlie the development of B-to-B alliances,

something that would allow firms to anticipate such conditions and

modify the structure of their relationship accordingly Powell [50].

Towards a Conceptual Framework

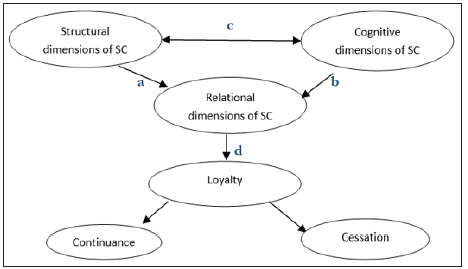

The model shown in Figure 1 reflects a causal ordering derived

from the literature reviewed and considers inter-relationships

between various SC dimensions and linking them to key aspects of

B-to-B collaborations. This continuum draws from research in the

field of ‘relationship marketing’ Dwyer [51], Crosby [52] in which

the aim is to strengthen existing relationships whilst increasing

loyalty Zeithaml [53].

In addition, social network theory Freeman [54] and social

exchange theory Blau [55] has been used a basis for the model as

synthesizing these theoretical perspectives enables the evaluation

of synergies among the SC dimensions (structural, cognitive and

relational) and loyalty. It is also aimed at supporting the premise

that B-to-B loyalty derive not only from the number of B-to-B

ties, the authority of the contact portfolio, and the interaction

amongst partner organizations Morgan [56], Siguaw [57]. For

example, social exchange theory suggests that commitment and

trust between two organizations are key drivers of loyalty, whereas

social network theory suggests that other attributes, such as the

level of interconnectedness among network entities, are key

determinants of performance and loyalty Wuyts [58]. Also, as B-to-B

exchanges often entail relationships and fall within the continuum

of organisation interaction, social network theory provides insight

into “missing” drivers of relationship loyalty between B-to-B

organizations. In addition, the agency theory approach has also

been applied to examine the special relationship that binds B-to-B

partnerships as this has been argued to be a useful first step in

diagnosing opportunities to advance co-operative behaviors Ellis

[59]. According to the agent theory, organizations enter into a

relationship because of the benefits of specialization and as a

means to control risk Logan [60].

Figure 1:Proposed B-to-B SC model.

The proposed model also builds on the theoretical framework

conceptualized by Moran [61], Nahapiet [62] which studied how

structural, relational and cognitive SC facilitate value creation

through combinations of exchange of resources. Here, Nahapiet

[62] relied on Granovetter [63] distinction between structural

and relational SC, which was also a distinction made in the work

of Lindenberg [64], Hakansson [65]. Within this, social interaction

remains key for structural SC as the contact’s location allows for

certain advantages. Here, organizations use their contacts to obtain

information or to access specific resources. Relational SC, in contrast,

refers to assets (such as trust and loyalty) that are rooted in these

relationships. Loyalty acts as a governance mechanism (and an

attribute) for relationships Uzzi [66] and since loyalty is prompted

by joint efforts Gambetta [67], Ring [68], a trusted organization

partner is more likely to obtain their organization partners’ loyal

support. Cognitive SC also facilitates an understanding of the

appropriate ways of acting in a social system and this is carried out

through collectivity as a resource Portes [69]. Moreover, cognitive

SC captures the essence of what Coleman [23] described as “the

public good aspect of social capital”. For example, a shared vision

or a set of common values in an organization assist in developing

SC’s cognitive dimension, which in turn facilitate actions that can

benefit the whole organization. As such the research narrative is

directed at analyzing the various SC dimensions and its effect on

the loyalty chain with objective-based indicators. The indicators

in question are in B-to-B contract cessation or/and continuance.

It also evaluates how SC in its cognitive, relational, and structural

forms contributes to or impedes loyalty as the three dimensions

capture a different aspect of B-to-B relationship. It is noted

though that loyalty intention is further enhanced when these

dimensions reinforce one another Palmatier [70]. The premise of

synergies among SC dimensions to loyalty is also consistent with

research in social networks. As Wuyts [58] summarize, different

aspects of network structure capture the “ability, opportunity,

and motivation” of network partners, and these characteristics

reinforce one another to enhance performance and loyalty. In

Figure 1, the SC dimensions of structural, relational and cognitive

‘arrows’ represent causal effect and direction. In other words, the

arrows between each dimension proposed influence lines between

one factor and another in a causal direction.

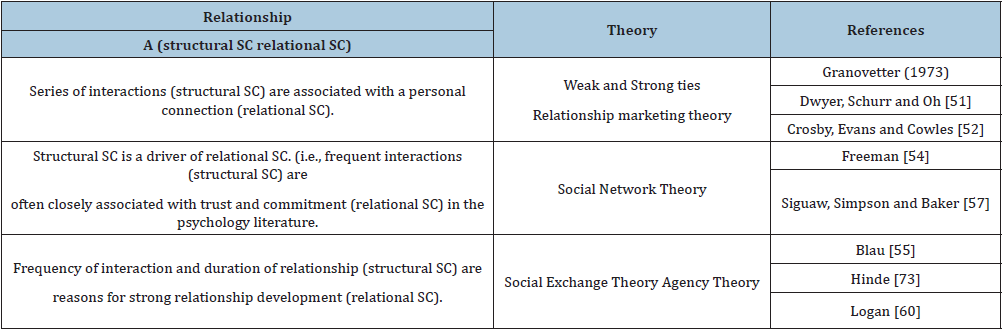

Table 1 describes the association of structural and relational

SC. This is evident in research conducted in relation to weak and

strong ties and the association between this and relational SC

stems from recent studies on customer-employee rapport Gremler

[71]. The study found that a series of interactions (structural SC)

are associated with a personal connection (relational SC). It also

follows studies which suggest that structural SC is a driver of

relational SC. For example, frequent interactions (structural SC) are

often closely associated with trust and commitment (relational SC)

in the psychology literature Fehr [72]. Hinde [73] also suggests that

frequency of interaction and duration of relationship (structural

SC) are highly cited reasons for strong relationship development

(relational SC).

Table 1: Describes the association of structural and relational SC.

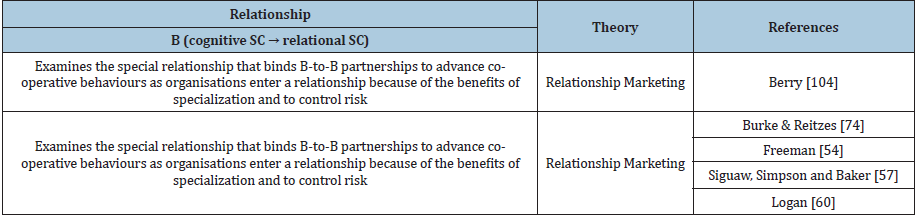

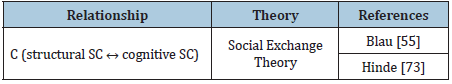

Table 2 describes the association of cognitive and relational SC and this initially stems from research pertaining to friendships and romantic partnerships. Here, studies have suggested that cognitive SC is an antecedent to relational SC Burke [74]. Moreover, close relationships are often formed within communities where the presence of shared meanings and norms (cognitive SC) allow for stronger ties (relational SC). Research in psychology also suggests that relationship strength is more likely to develop sooner within groups than with outsiders Hinde [73] and thus this is expected to follow suit in the B-to-B context. Table 3 describes the association of structural SC to cognitive SC This is where the structural and cognitive SC association rely on the premise that social interactions play a critical role both in shaping a common set of organization values and goals Hinde [73].

Table 2:Describes the association of cognitive and relational SC and this initially stems from research pertaining to friendships and romantic partnerships.

Table 3:describes the association of structural SC to cognitive SC.

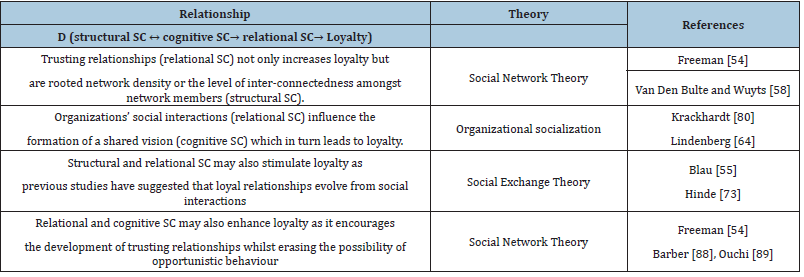

Table 4 describes the association of all three SC dimensions to loyalty. Here, Sitkin [75] maintained that trusting relationships (relational SC) not only increases loyalty but are rooted network density or the level of inter-connectedness amongst network members (structural SC). Network research shows that these forms of network inter-connectedness positively affect cooperation, knowledge transfer, communication efficiency, and product development performance Rowley [76], Sai [77] and Walker [5]. More network partners (structural SC) also provide access to and control more valuable information and resources, which supports increased value creation (and loyalty) from network ties Baum [78], Burt [34]. Hence, an organization occupying a central location in a social interaction network is likely to have higher loyalty ties to other organizations in the network Granovetter [79]. Thus, organizations are more inclined to be loyal, as they can expect to work towards collective goals and will not be hurt by the pursuit of self-interest. Krackhardt [80] also posited that the organizations’ social interactions (relational SC) often influence the formation of a shared vision (cognitive SC). Here, the literature on organizational socialization. Lindenberg [64] highlighted the importance of informal social interaction in forming loyalty ties. Hence, frequent and close social interactions permit organizations to know each other, share important information whilst creating common views. For example, the social interaction process has led organizations to realize and adopt languages, codes and practices and may share a collective orientation toward the pursuit of similar goals and plans. This constitutes the vision and therefore organizations are more likely to maintain loyalty with other business units in the network Nahapiet [62].

Table 4:Describes the association of all three SC dimensions to loyalty.

Rusbult [81] investment model of commitment also depicts

the positive link between investment and loyalty - a proxy for

relational SC. Structural and relational SC may also stimulate

loyalty as previous studies have suggested that loyal relationships

evolve from social interactions Gulati [82], Granovetter [79]. As

organizations interact over a period of time, relationship quality

become more concrete Gabarro [83] and this enhances cooperative

behaviors, which in turn affects decisions that increases loyalty

Donaldson [84]. High-quality relationships are also a result of

trust, commitment, and reciprocity and entail an efficient cost of

maintaining the relationship with a “minimum of hassles” Wulf [85].

Moreover, the network literature has documented the implications

of strong social interaction for trust and loyalty Krackhardt [86].

Thus, in a B-to-B context, relationships that include interpersonal

ties can better uncover key information, build strong B-to-B

relationships, and influence behaviors beyond the contractual

setting Bendoly [87], Granovetter [79].

Relational and cognitive SC may also enhance loyalty as it

encourages the development of trusting relationships whilst

erasing the possibility of opportunistic behaviour Barber [88],

Ouchi [89]. In this regard, relational SC entails the strength of the

relationship built over time, whereas cognitive SC refers to the

commitment to align cultures and goals within the relationship.

Overall, this model poses the ‘how’ question for inter-firm alliances

and highlights important sets of conditions deriving from the use of

SC dimensions (in the context of social networks firms are placed

in), which in turn influences their behaviour, and ultimately the

continuance or cessation of the partnership. The benefits to the

firm of cognitive, relational and structural SC result in loyalty but

to what extent is the relation forms core of this research study.

Thus, an understanding of the significance of SC’s three dimensions

that influence alliance formation provides insights for managers

on the path-dependent processes that may lock them into certain

courses of action, as a result of constraints from their current ties.

Such concerns can then be anticipated and thus can be proactively

initiated to enhance their informational capabilities. In another

instance, a potential advantage can stem from economies of scope

and applying relevant resources in different contexts. In a similar

light, and in relation to transactional costs, the costs of maintaining

the network are in the management of information (structural SC)

and mutual leniency, reinforcing trustworthy behaviour (relational

SC) whilst underscoring network commitment (cognitive SC) and

having a good grasp of how these interact and influence each

other in loyalty building will be useful. For example, loyalty can

be a ‘cause’ of both continuance and cessation which the various

dimensions of SC are interrelated to ‘cause’ loyalty. Effective B-to-B

relationships are of core importance and building (and sustaining)

long-term relationships serve as a key target for successful business

activities. Heskett [90] first point to loyalty as the essential element

or condition of an effective business strategy. The economic value of

loyalty also has been discussed by Jones [91], Reichheld [92], where

a complete understanding of the concept of loyalty highlights the

need for a balance of value between businesses and the need to

develop loyalty as a long-term investment. Thus, the benefits to the

firm of SC, resident within the relationship, are the generation of

loyalty. Besides, a number of loyalty indicators are evident in the

services literature and this includes concepts such as ‘repurchase

intentions’ and willingness to pay more Barry [93], Saura G [94],

Mosisescu [95] and in the models’ case, ‘cessation’ and ‘continuance’.

Furthermore, Palmatier [70] asserts that firm loyalty has proven to

be key in determining the health of B-to-B relationships. So how

does inter-firm trust lead to greater loyalty? Knowledge-based

trust (resulting from mutual awareness) and deterrence-based

trust (resulting from reputational concerns) results in ‘contractual

safeguards’, leading to greater loyalty Bradach [96], Powell [50]. As

a result, contractual concerns are more likely to be alleviated when

trust is established, and this is due to the social network existence

Gulati [39]. This is where the various dimensions of SC can be

studied.

Whenever two firms enter an alliance, whatever its exact

institutional structure, their network proximity is posited to

influence the specific governance structure used to formalize the

alliance Gulati [47]. Also, the extent to which two partners are

socially embedded can influence their preceding behaviour and

affect the alliance future success. Moreover, a firm’s portfolio of

alliances and its network position can have a profound influence

on its overall performance Gulati [39] and as such exploring

the development of B-to-B SC can play an important role. The

conceptual framework above provides greater insights into

the potential evolution of networks, where strategic action and

social structure are closely intertwined. This facilitates greater

understanding of the extent to which B-to-B alliances are locked

into path-dependent courses of action as it allows firms to also

be able to select path-creation strategies Garud [97]. As a result,

firms can then visualize the desired network structure of alliances

in the future and work backwards to define their current alliance

strategy. Gulati [39], also observed that firms which independently

initiated new alliances turned to their existing relationships first

for potential partners. The manner and extent to which were

embedded were likely to influence key decisions, their choice of partner, the type of contracts used, and how the alliance developed

and evolved over time. Gulati [39], fieldwork concluded that prior

ties in social networks influenced the creation of new ties whilst also

affecting their design, their evolutionary path, and their ultimate

success. A similar orientation also can be applied for studying the

consequences of B-to-B SC alliances. Here, firms entering alliances

can use social networks as SC becomes a basis for competitive

advantage Burt [98]. Moreover, firms are able to extract superior

terms of trade because of possible control benefits as a result of

SC. Therefore, the informational benefits from social networks can

have implications for the growth and corresponding success of the

alliance itself.

Eisenhart [41], in their study, also determined that alliances

form when firms are in vulnerable strategic positions either

because they are competing in highly competitive industries or

because they are attempting to pioneer technical strategies. Their

findings also conclude that alliances form when firms are in strong

social positions such that they are led by large, experienced, and

well-connected top management teams. Overall, this conceptual

framework forms part of building blocks and allows one to

distinguish how the context of the society that is being studied

differs from other studies in existing literature. This method is

in line with the practice proposed by Inkpen [99]. Incorporating

social network factors into firms’ alliance behaviour also provides

a more accurate representation of key indicators which influences

strategic actions of firms, and this has implications for managerial

practice, which has so far been underexplored.

A Proposed Research Agenda and Potential Research Method

It has been argued that SC is a useful concept to incorporate into

IB research into B-to-B relationships (and by extension relationships

with consumers). But how could this usefully be done? A way

forward is proposed, and this consist of specific research questions,

case analysis and particular data collection methods and analysis.

This discussion will be brief but useful to touch on because of its

potential practical implications in the business arena. Because SC

and B-to-B relationships are so contextually specific, and because

relatively little is known about the causes and effects at present in

IB systems, several research questions appear paramount:

“How can businesses entering strategic alliances with other

businesses use social capital to manage B-to-B relationships and

enhance loyalty?”

This is elaborated by the following sub-questions:

A. What aspects of the SC dimensions play a more critical

role in influencing loyalty intentions?

B. How can the B-to-B relationship be managed to support,

plan and assess the activities which influence loyalty intentions?

These questions are highly contextual. As relationships are

central to SC, it is argued that case research is best suited to exploring

SC in a B-to-B context, both to validate the proposed framework and

to properly amend and adjust it. Case research also allows a more thorough investigation of the B-to-B phenomenon in the IB context

as concrete nature of case study evidence is more cogent than

statistical findings Dickson [100]. A useful methodology to address

the research question(s) is by comparative case studies through

interpretive analysis, using the proposed model whilst applying

phenomenological and explanatory research (i.e., asking ‘how’

and ‘why’ types of questions). Two primary methods of gathering

data are through company files, archival documents and in-depth

interviews with B-to-B managers. Interviews in particular could

explore in detail the respondent’s own perceptions and accounts

on their B-to-B relationship and apply ‘convergent interviewing’

by gathering insights into respondents’ views and attitudes about

their B-to-B relationship, and their perceptions about why and how

firms build relationships.

To further validate the research questions, a quantitative study

is recommended with the following propositions to test.

A. Significance of SC’s relational dimension to loyalty:

1. The greater the trust between firms the greater the loyalty

2. The greater the commitment between firms the greater

the loyalty

3. The greater the reliability between firms the greater the

loyalty

4. The greater the long-term commitment between firms the

greater the loyalty

5. The greater the satisfaction between firms the greater the

loyalty

B. Significance of SC’s structural dimension on loyalty:

1. The greater the social interaction between firms the

greater the loyalty

2. The greater the communication intensity between firms

the greater the loyalty

3. The greater the resource exchange between firms the

greater the loyalty

4. The greater the network ties between firms the greater

the loyalty

C. Significance of SC cognitive dimension on loyalty:

1. The greater the shared vision between firms the greater

the loyalty

2. The better the managerial skills between firms the greater

the loyalty

3. The greater the person-related competencies between

firms the greater the loyalty

Comparative case studies as described above, together with company documentary evidence can result in case descriptions useful to forming an understanding of the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of SC dimensions and successful B-to-B collaborations. These can provide templates for more generalized data collection and analysis.

Conclusion and Directions for Future Research

SC derived from B-to-B relationships can impact its bottom line

whilst the interactions establish a pattern of expectations based

on norms of reciprocity and equity. If these two patterns persist,

the sum of resources that accrue to a business transpires and an

SC base is built. Thus, an understanding of SC’s nature in IB is

necessary because it is a key element of a business’s competitive

advantage. A synthesis of the literature on B-to-B SC and loyalty

into a single, process-based framework has been presented here.

The literature suggests that stronger relationships, shared beliefs

between partners, and multiplex ties result in higher SC. This

approach redefines relationships by expanding on the present

understanding of SC dimensions and offers insights into alliance

formation in IB. It also provides an understanding of how B-to-B

relationships, as understood via the established SC dimensions

(i.e., relational, cognitive and structural), underpin networks and

alliances that are salient to IB.

By examining the specific way in which social networks (via

SC dimensions) influence firms’ future actions, firms can begin to

take a more pro-active stance in the new ties they enter. This will

be in designing networks, outlining implications on future partners

and also in obtaining control benefits. Similarly, there are several

insights that result from understanding the complexities associated

with managing a portfolio of alliances and relational capabilities.

Ultimately, managers want to know how to manage B-to-B alliances,

and the recognition of B-to-B SC dimension dynamics that influence

the performance of alliances can be extremely beneficial. The

challenge for scholars studying networks and alliances is to bridge

the gap between theory and practice and translate some of their

important insights for managers of the alliances.

The proposed model is also specifically intended to explore

the inter-dependence of SC, embedded in B-to-B relationships as a

greater understanding of SC dimensions can be valuable conduits

of information that provide both opportunities and constraints

for firms. It can also have important behavioural and performance

implications for their B-to-B alliances, as by channeling information,

the management of SC dimensions will enable firms to discover

new alliance opportunities and can thus influence how often and

with whom those firms enter into alliances.

Hence, empirical testing is required as it has the potential to

provide managerially relevant (“actionable”) results in ‘how’ and

in ‘what way’ B-to-B SC can be harnessed in IB. Research along this

path also further expands understanding of SC’s role in altering

existing B-to-B exchange relationships and the manner by which

firms use alliances to create and add value. It also adds to the limited

literature on B-to-B service relationships in a global context whilst

having the potential to provide managerially relevant (“actionable”)

results in ‘how’ and in ‘what way’ B-to-B SC can be harnessed in the

21st century IB system. There are, of course, limitations to this, as

any, model, and a number of issues should be further addressed.

One has already been noted in the earlier discussion of strategic

alliances, namely the fact that SC can have costs as well as benefits.

These are more diffuse and subtle than those under a transaction’s

costs rubric, but they must be kept in mind in any future study. Not

all relationships are worth having (or continuing) and the SC capital

they create may be value-destroying in some cases.

There are also important cross-cultural issues. In China, ‘guanxi’

plays a pivotal role in building B-to-B relationship. How does this

relate to SC? In this particular case the properties of ‘guanxi’ can

be seen as the result of the interplay between resource scarcity and

Chinese cultural context, low trust-radius, familyism, and the lack

of overarching norms, in effect both a possible cause and an effect

of SC and one where business and personal spheres are often highly

mixed. Li Y [101] proposed a type of network-based SC which

account for the dynamics (and its dimensions), comprising of dense

strong ties accompanied by sparse weak ties. On the other hand, the

boundary between business and social lives in Western countries is

more unambiguous and thus individuals tend to separate business

and social networks. Here, the SC concept and formulation will be

somewhat different than in China and other non-western societies

(and, indeed, this paper has implicitly been based in the western

paradigm) [102-108].

References

- Mathews C (1999) Managing international joint ventures. Kogan Page Limited, London, UK.

- Peng MW (2003) Institutional transitions and strategic choices. Academy of Management Review 28(2): 275-296.

- Buckley P (2011) International integration and coordination in the global factory. Management International Review 51: 269-283.

- Dunning J (2015) The globalisation of business. Routledge, New York, USA.

- Walker G, Kogut B, Shan W (1997) Social capital, structural holes, and the formation of an industry network. Organisational Science 8(2): 109-125.

- Nahapiet J, Ghoshal S (1998) Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review 23(2): 242-266.

- Moran P (2005) Structural vs relational embeddedness: Social capital and managerial performance. Strategic Management Journal 26(12): 1129-1151.

- Porter ME (1980) Competitive strategy. Free Press, New York, USA.

- Barney JB (1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management 17(1): 99-120.

- North DC (1990) Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Cambridge Harvard University Press, Massachusetts, USA.

- Oliver C (1997) Sustainable competitive advantage: Combining institutional and resource-based views. Strategic Management Journal 18(9): 679-713.

- Williamson OE (2000) The new institutional economics: Taking stock, looking ahead. Journal of Economic Literature 38(3): 595-613.

- Hall P, Soskice D (2001) An introduction to varieties of capitalism. Oxford University Press, UK.

- Narula R (2006) Globalization, new ecologies, new zoologies, and the purported death of the eclectic paradigm. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 23: 143-151.

- Gulati R (1998) Alliances & networks. Strategic Management Journal 19(4): 293-317.

- Auster E (1994) Macro and strategic perspectives on inter-organizational linkages: A comparative analysis and review with suggestions for reorientation. In: Shrivastava P, Huff AS, Dutton JE (Eds.), Advances in Strategic Management 10: 3-40.

- Chan J, Pun N, Seldon M (2013) The politics of global production: Apple, Foxconn and China's new working-class new technology. New Technology, Work and Employment 28(2): 100-115.

- Lashinsky A (2012) Inside Apple London. John Murray, UK.

- Satariano A, Burrows P (2011) Apple's supply-chain secret? Bloomberg business week, USA.

- Hagedoorn J, Duysters G (2002) Satisfying strategies in dynamic inter-firm networks the efficacy of quasi-redundant contacts. Organization studies 23: 525-666.

- Kay N (1997) Pattern in corporate evolution. Oxford University Press, London, UK.

- Knoke D, Kuklinski JH (1982) Network analysis. Beverly Hills, Canada.

- Coleman J (1990) Foundations of social theory. Cambridge Harvard University Press, London, UK.

- Burt RS (2000) The network structure of social capital. Research in Organizational Behaviour 22: 345-423.

- Adler PS, Kwon SW (2002) Social capital: Prospects for new concept. Academy of Management Review 27(1): 17-40.

- Krause D, Handfield R, Tyler B (2006) The relationship between supplier development, commitment, social capital accumulation and performance improvement. Journal of Operations Management 25(2): 528-545.

- Eklinder F, Eriksson JLT, Hallen L (2014) Multidimensional social capital as a boost or a bar to innovativeness. Industrial Marketing Management 43(3): 460-472.

- Bourdieu P (1985) The forms of capital. Greenwood, New York, USA.

- Portes A (1988) Social capital: Origins and applications. Annual review of sociology 24: 1-24.

- Putnam R (1995) Bowling alone: America's declining social capital. Journal of Democracy 6(1): 65-78.

- Lin N (1999) Building a network theory of social capital. Connections 22(1): 28-51.

- Cohen D, Prusak L (2001) In good company: How social capital makes organizations work. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

- Jones T, Taylor SF (2012) Service loyalty: Accounting for social capital. Journal of Services Marketing 26(1): 60-75.

- Burt RS (1992) Structural holes: The social structure of competition. Harvard University Press, London, UK.

- Granovetter MS (1995) The economic sociology of firms and entrepreneurs. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, USA.

- Barnes JG (1997) Closeness, strength, and satisfaction: Examining the nature of relationships between providers of financial services and their retail customers. Psychology and Marketing 14(8): 765-790.

- Bansal HS, Irving PG, Taylor SF (2004) A three component model of customer commitment to service providers. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 32(3): 234-250.

- Kogut B, Shan W, Walker G (1992) The make or-cooperate decision in the context of an industry network. In: Nohria N, Eccles R (Eds.), Networks and organizations. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

- Gulati R (1997) Which firms enter into alliances? An empirical assessment of financial and social capital explanations. Northwestern University, Illinois, USA.

- Podolny JM, Stuart T (1995) A role-based ecology of technological change. American Journal of Sociology 100(5): 1224-1260.

- Eisenhart K, Schoonhoven CB (1996) Resource-based view of strategic alliance formation: Strategic and social effects in entrepreneurial firms. Organisation Science 7(2): 136-150.

- Kogut B (1989) The stability of joint ventures: Reciprocity and competitive rivalry. Journal of Industrial Economics 38(2): 183-198.

- Levinthal DA, Fichman M (1988) Dynamics of inter-organizational attachments: Auditor-client relationships. Administrative Science Quarterly 33(3): 345-369.

- Seabright MA, Levinthal DA, Fichman M (1992) Role of individual attachment in the dissolution of inter-organizational relationships. Academy of Management Journal 35(1): 122-160.

- Heide J, Miner A (1992) The shadow of the future: Effects of anticipated interaction and frequency of contact on buyer-seller cooperation. Academy of Management Journal 35(2): 265-291.

- Parkhe A (1993) Strategic alliance structuring: A game theoretic and transaction cost examination of interfirm cooperation. Academy of Management Journal 36(4): 794-829.

- Gulati R (1993) The dynamics of alliance formation, unpublished doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts, USA.

- Zaheer A, Zaheer S (1997) Catching the wave: Alertness, responsiveness and market influence in global electronic networks. Management Science 43(11): 1493-1509.

- Medlin CJ (2004) Interaction in business relationships: A time perspective. Industrial Marketing Management 33(3): 185-193.

- Powell WW, Koput K, Smith LD (1996) Inter-organizational collaboration and the locus of innovation: Networks of learning in biotechnology. Administrative Science Quarterly 41(1): 116-145.

- Dwyer FR, Schurr PH, Oh S (1987) Developing buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing 51(2): 11-27.

- Crosby L, Evans K, Cowles D (1990) Relational benefits in service industries: The customer's perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 26(2): 101-114.

- Zeithaml VL, Berry, Parasuraman A (1996) The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing 60(4): 31-46.

- Freeman L (1979) Centrality in social networks: Conceptual clarification. Social Network 1(3): 215-239.

- Blau P (1968) Social exchange. In: Sills DL (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social sciences. New York, USA, pp. 452-457.

- Morgan RM, Hunt SD (1994) The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing 58(3): 20-38.

- Siguaw JA, Simpson PM, Baker TL (1998) Effects of supplier market orientation on distributor market orientation and the channel relationship: The distributor perspective. Journal of Marketing 62(3): 99-111.

- Bulte C, Wuyts S (2007) Social networks and marketing. Marketing Science Institute, Massachusetts, USA.

- Ellis S, Johnson L (1993) Observations: Agency theory as a framework for advertising agency compensation decisions. Journal of Advertising Research 33(5): 76-80.

- Logan M (2000) Using agency theory to design successful outsourcing relationships. The International Journal of Logistics Management 11(2): 21-32.

- Moran P, Ghoshal S (1996) Value creation by firms. Academy of Management Best Paper Proceedings, pp. 41-45.

- Nahapiet J, Ghoshal S (1997) Social capital, intellectual capital and the creation of value in firms. Academy of Management Best Paper Proceedings, pp. 35-39.

- Granovetter MS (1992) Problems of explanation in economic sociology. In: Nohria N, Eccles R (Eds.), Networks and organizations: Structure, form and action. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, pp. 25-26.

- Lindenberg S (1996) Constitutionalism versus rationalism: Two views of rational choice sociology. In: Clark J (Ed.), London, UK, pp. 299-311.

- Hakansson H, Snehota I (1995) Developing relationships in business networks. Routledge, London, UK.

- Uzzi B (1996) The sources and consequences of embeddedness for the economic performance of organizations: The network effect. American Sociological Review 61(4): 674-698.

- Gambetta D (1988) Can we trust? In: Gambetta D (Ed.), Trust: Making and breaking cooperative relations. Basil Blackwell, New York, USA, pp. 213-238.

- Ring PS, Ven AH (1994) Developmental processes of cooperative inter-organizational relationships. Academy of Management Review 19(1): 90-118.

- Portes A, Sensenbrenner J (1993) Embeddedness and immigration: Notes on the social determinants of economic action. American Journal of Sociology 98(6): 1320-1350.

- Palmatier R, Dant R, Grewal D, Evans K (2006) Factors influencing the effectiveness of relationship marketing: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marketing 70(4): 136-153.

- Gremler DD, Gwinner KP (2000) Customer employee rapport in service relationships. Journal of Service Research 3(1): 82-104.

- Fehr B (1996) Friendship processes. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA.

- Hinde RA (1979) Towards understanding relationships. Academic Press, New York, USA.

- Burke PJ, Reitzes DC (1991) An identity theory to commitment. Social Psychology Quarterly 54(3): 239-251.

- Sitkin SB, Roth NL (1993) Explaining the limited effectiveness of legalistic remedies for trust/distrust. Organization Science 4(3): 367-392.

- Rowley TJ (1997) Moving beyond dyadic ties: A network theory of stakeholder influences. Academy of Management Review 22(4): 887-910.

- Sai W (2001) Knowledge transfer in inter-organizational networks: Effects of network position and absorptive capacity on business unit innovation and performance. Academy of Management Journal 44(5): 996-1001.

- Baum JAC, Calabrese TC, Silverman BS (2000) Don’t go it alone: Alliance network composition and startups’ performance in Canadian biotechnology. Strategic Management Journal 21(3): 267-94.

- Granovetter MS (1985) Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology 91(3): 481-510.

- Krackhardt D (1990) Assessing the political landscape: Structure, cognition, and power in organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly 35(2): 342-369.

- Rusbult CE (1980) Satisfaction and commitment in friendships. Representative Research in Social Psychology 11(2): 96-105.

- Gulati R (1995) Does familiarity breed trust? The implications of repeated ties for contractual choice in alliances. Academy of Management Journal 38(1): 85-112.

- Gabarro JJ (1978) The development of trust, influence, and expectations. In: Athos AG, Gabarro JJ (Eds.), Interpersonal behaviors: Communication and understanding in relationships, pp. 290-303.

- Donaldson L (2001) The contingency theory of organizations. Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, CA, USA.

- Wulf K, Schröder GO, Iacobucci D (2001) Investments in consumer relationships: A cross-country and cross-industry exploration. Journal of Marketing 65(4): 33-50.

- Krackhardt D (1992) The strength of strong ties: The importance of Philos in organizations. In: Nohria N, Eccles RG (Eds.), Networks and organizations: Structure, form and action, pp. 216-239.

- Bendoly E, Croson R, Goncalves P, Schultz K (2010) Bodies of knowledge for research in behavioral operations. Journal of Operations Management 19(4): 434-452.

- Barber B (1983) The logic and limits of trust. New Brunswick, Australia.

- Ouchi VG (1980) Markets, bureaucracies, and clans. Administrative Science Quarterly 25(1): 129-141.

- Heskett J, Sasser WE, Schlesinger LA (1997) The service profit change: How leading companies link profit and growth to loyalty, satisfaction and value. New York, USA.

- Jones TO, Sasser E (1995) Why satisfied customers defect, pp. 88-99.

- Reichheld FF (1996) Learning from customer defections. Harvard Business Review 74(2): 56.

- Barry JP, Dion, Johnson W (2008) A cross-cultural examination of relationship strength in B2B services. Journal of Services Marketing 22(2): 114-135.

- Saura GI, Frasquet DM, Cervera AT (2009) The value of B2B relationships. Industrial Management and Data Systems 109(5): 593-609.

- Mosisescu O, Allen B (2010) The relationship between the dimensions of brand loyalty: An empirical investigation among Romanian urban consumers. Management & Marketing 5(4): 83-98.

- Bradach JL, Eccles RG (1989) Markets versus hierarchies: From ideal types to plural forms. In: Scott WR (Ed.), Annual Review of Sociology 15: 97-118.

- Garud R, Rappa M (1994) A socio-cognitive model of technology evolution. Organization Science 5(3): 344-362.

- Burt RS (1997) The contingent value of social capital. Administrative Science Quarterly 42(2): 339-365.

- Inkpen A, Sang ET (2005) Social capital, networks and knowledge transfer. Academy of Management Review 30(1): 146-165.

- Dickson PR (1982) The impact of enriching case and statistical information on consumer judgements. Journal of Consumer Research 8(4): 398-406.

- Li Y, Si S (2007) Organizational learning approaches and management innovation: An empirical study in Chinese context. Journal of Current Issues in Finance, Business and Economics 1(2): 1-10.

- Bagdonienė L, Jakštaitė R (2009) Trust as basis for development of relationships between professional service providers and their clients. Economics and management 14: 360-366.

- Bartlett CA, Goshal S (1999) Managing across borders: The transnational solution. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

- Berry LL (1983) Relationship marketing. In: Berry LL, Shostack GL, Upah G (Eds.), Emerging perspectives on services marketing. Chicago, USA, pp. 25-28.

- Berry VA, Parasuraman, Zeithaml V (1996) The behavioural consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing 60(2): 31-46.

- Gebert H, Geib M, Kolbe L, Brenner W (2003) Knowledge-enabled relationship management: Integrating customer relationship management and knowledge management concepts. Journal of Knowledge Management 7(5): 107-123.

- Ghernawat P (2007) Redefining global strategy: Crossing borders a world where differences still matter. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

- Jaakkola E, Halinen A (2006) Problem solving within professional services: Evidence from medical field. International Journal of Service Industry Management 5: 409-429.

© 2021 Cameron Gordon. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)