- Submissions

Full Text

Strategies in Accounting and Management

The Characteristics of Bribe-Taking by Chinese High-Level Officials

Huai Yuan Han1*, Lotfi Hamzi1, Thierry Côme2 and Gilles Rouet2

1LAREQUOI management research laboratory, ParisSaclay University, France

2NEOMA Business School, France

*Corresponding author: Huai Yuan Han, LAREQUOI management research laboratory, ParisSaclay University, France

Submission: September 09, 2019; Published: August 25, 2020

ISSN:2770-6648Volume1 Issue5

Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this paper is to analyze in detail the characteristics of bribe-taking by provincial and ministerial or senior-level officials.

Methodology: In this paper, we analyze the data concerning all provincial and ministerial level officials convicted of bribe-taking apart from army generals. We identify 110 cases between 1987 and the end of 2015, of which 76 cases involved bribery alone and the rest also involved other crimes.

Findings: The achievements of China's economic reforms and opening-up over the last 30 years are obvious to all, but they have encouraged significant problems of corruption by senior party and government officials. Between 1987 and 2015 the number of officials convicted of corruption grew significantly and, sentences became more severe. Since 1987, the amount of bribery has increased steadily, and the time span of corruption has increased. Corrupt officials mostly use traditional kinds of exchange of interests, and corruption in China has spread into every part of society. China still has a long way to go if it is to win the fight against corruption.

Keywords: China; Corruption; Power; Self interest

Introduction

China is undergoing unprecedented change, which requires us to advance our understanding of this country constantly. To understand China well, it is necessary to investigate not only the factors that will promote its further economic development, but also those that could hinder its social progress. Thirty years of reform and liberalization have brought China substantial increases in living standard together with corruption at different levels due to the lure of material gain and the imperfect legal system Liang [1] & Dong [2]. Studies of this increasingly serious problem of corruption can give foreign investors, among others, a better understanding of China’s society and investment environment.

Faced with growing bribery, the Chinese government has taken a series of anti-corruption measures Gong [3] & Yao [4]. Since the 18th National Congress of the CPC on November 8, 2012, the CPC authorities and the Chinese government led by Xi Jinping have increased the intensity of its investigation of corruption cases against officials, especially high-ranking, to an unprecedented level Guo & Li [5]. By the end of 2015, more than 120 provincial and ministerial level officials had been removed from their positions (News Xinhua, 2016).

Research Objectives

In China, the crime of bribe-taking is defined by Article 385 of Chinese Criminal Code as “state officials who take advantage of their office to demand money or goods from other people, or who illegally accept money or goods from other people and give favors in return” (Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China, 1997). Our research will focus on the detailed characteristics of bribe-taking by provincial and ministerial or senior-level officials. It will consider only public officials, including staff in the Chinese Communist Party (CPC), government, legislature, judiciary and State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), who have been convicted by the courts and whose sentences have been officially announced.

Methodology

In this paper, we analyze all provincial and ministerial level officials convicted of bribery (or more precisely, of bribe-taking) apart from army generals. We identified 110 cases between 1987 and the end of 2015, of which, 76 cases involved bribery alone (for example, in 2011, HUANG Sheng, former Deputy Governor of Shandong province, was convicted of Bribery) and the rest also involved other crimes (for example, in 2005, LIU Jinbao, former President of Bank of China (Hong Kong), was convicted of Bribery, Embezzlement and Misappropriating public funds).

To obtain more precise results, in the case of multiple crimes, we only consider the part of the sentence for bribery. For example, in the case of LIU Jinbao, we only considered the 12 years of imprisonment for Bribery in our analysis, although he was sentenced to death suspended for two years. However, when it was impossible to obtain information about the specific conviction for bribery in a case, we did not include this case in our analysis of average time span of case of bribery of Chinese high-level officials. For example, XU Jinbao was found guilty of various crimes between 1993 and 2003, but information about when he took bribes is unavailable. Through an analysis of 110 cases of bribery, our research reveals the features of bribe-taking by Chinese provincial and ministerial level officials.

Data Analyses

Area distribution of the convicted officials

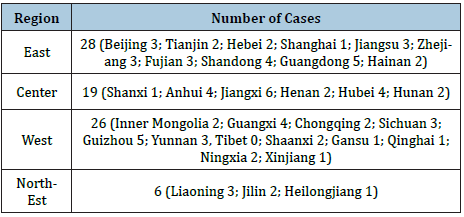

Beside 20 cases that occurred in various central ministries and agencies and 11 cases in state-owned enterprises, the other 79 cases are widely distributed between different provinces, autonomous regions or cities, except Tibet (Table 1).

Table 1: Corrupt officials almost all over the country.

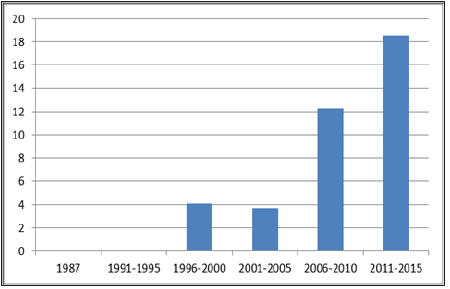

Trends in number of convictions, 1987-2015

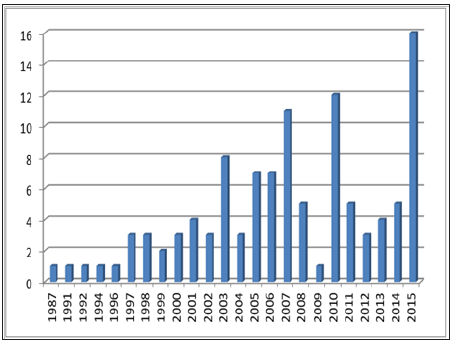

Apart from victims of political struggles within the party, almost no provincial and ministerial level officials were punished because of corruption in the 30 years following the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Although the Tianjin Party Secretary and Shijiazhuang vice Party Secretary were sentenced to death for corruption in 1952, there were only bureau-level officials. In February 1987 Hong Qingyuan, former Secretary-General of the Party Committee of Anhui Province, was sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment for bribery. He is considered the first provincial and ministerial level cadre sentenced for corruption. The number of provincial and ministerial level officials convicted of bribery increased from 1 case in 1987 to 16 cases in 2015, presenting a clear upward trend (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Number of officials sentenced.

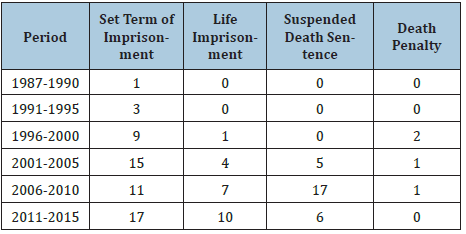

Sentences received (only for the crime of taking bribes)

In 1999, for the first time in the history of Chinese Communist Party’s anti-corruption measures, a provincial/ministerial official, Xu Bingsong, sentenced to life imprisonment for the crime of bribe-taking. In 2000, a provincial/ministerial level official, Cheng Kejie, was condemned to death, an unprecedented sentence for bribery. In 2001, the first senior official convicted of taking bribes, Li Jizhou, who received a suspended death sentence. However, the data collected shows us that from the beginning of the 21st century, the CPC and the Chinese government significantly increased their efforts to combat the bribery of senior officials (Table 2).

Table 2: Sentences in different period.

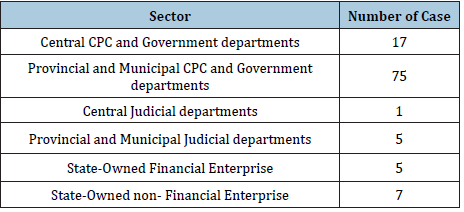

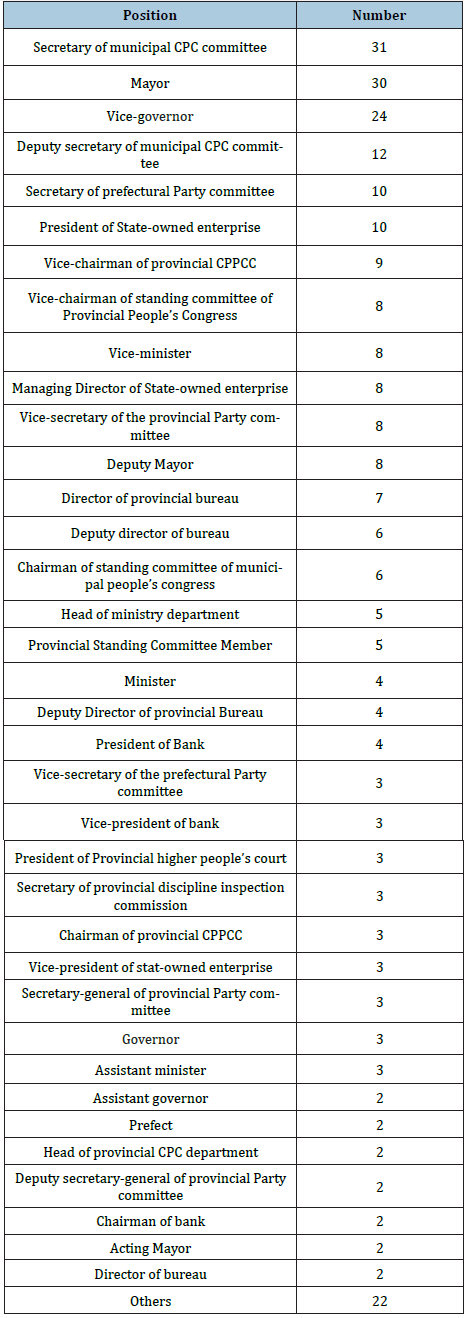

Last position

According to our data, the 110 dismissed officials occupied 35 different positions. Forty-five of the case are concentrated on three positions (Vice-governor, Vice-chairman of the Standing Committee of the Provincial People’s Congress and Vice-chairman of the provincial CPPCC); the rest are widely distributed among different positions. Otherwise, we can find that the 110 last posts are mainly distributed in the following areas (Table 3).

Table 3: Sectors of corrupt officials’ last position.

Crimes committed

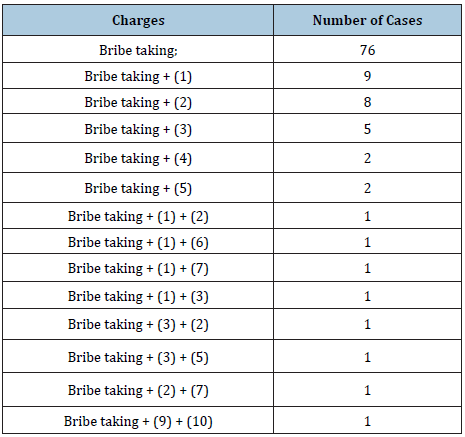

Of the 110 cases, 76 resulted in conviction for the crime of bribery alone. In the remaining 34 cases, the convictions were for one or more other offenses in addition to bribery (Table 4).

Table 4: Distribution of charges.

Time-span of corruption (taking bribes)

For each case, as the following example shows, it’s possible to find the duration of the crime. The Court’s Judgment for Zhu Zuoyong, former Vice-chairman of Gansu Province CPPCC: “Upon trial, the court found that from April 1994 to September 2004, the defendant Zhuzuo Yong used his position as Vice-chairman of Gansu Province CPPCC and Mayor of Lanzhou City to seek benefits for others and illegally accept money and goods of a total value of RMB 170 million”.

A. Two of the 110 cases were not included when calculating the time-span of the crimes: B. Hong Qingyuan, due to lack of necessary information. C. Zhou Yongkang, due to lack of necessary information. D. The average time-span for the 108 cases was 97.02 months (8.08 years).

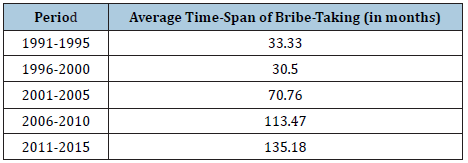

The following table and graph compare the average timespan of taking bribes in the different periods (Table 5).

Table 5: Average time-span of bribe-taking (108 cases) in the different periods.

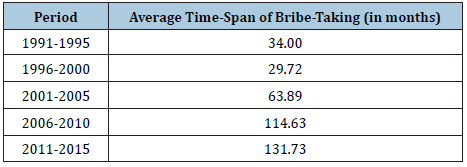

Given that 34 cases involving more than one kind of crime, we also calculated the timespan of the 76 cases involving the bribetaking alone. One of the total 76 cases was not included in the calculation of the time-span: The case of Hong Qingyuan, due to a lack of necessary information The average time-span for the 75 cases of bribe-taking was 92.32 months (7.69 years) The longest time-span was the case of Yang Baohua, former Chairman of Hainan province CPPCC: 216 months (18 years) The shortest time-span was the case of Hou Wujie, former Vice-secretary of Shanxi Province: 2 months (0.16 years) (Table 6). Whether bribe-taking was the only crime involved or other crimes were also involved, the timespan of the crimes has become steadily longer.

Table 6:Average time-span of bribe-taking (75 cases) in the different periods.

The administrative positions in which the exchanges of interest occurred

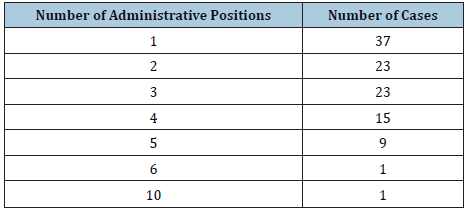

Depending on the time span of the crime, officials may carry out the exchange of interests in different administrative positions. Our study reveals in what positions illegal exchange of interest can be conducted. The analysis included 109 cases in all, but we omitted were included in the analysis but the case of Zhou Yongkang due to a lack of detailed information (Table 7).

Table 7: Most corrupt officials involved two or more positions.

We find that of the 109 cases, 72 cases involved two or more positions, and the highest number was 10 in the case of Chen Anzhong, former Deputy Director of Jiangxi Province People’s Congress. Our research shows that the illegal exchange of interest occurred in 61 different positions (Table 8). In fact, one official can carry out illegal interest exchange of interest in different positions, for example Chen Anzhong, former Deputy Director of People’s Congress of Jiangxi Province, committed crimes in ten different administrative posts: Deputy Secretary of Hengyang; Deputy Mayor of Hengyang; Mayor of Hengyang; Deputy Secretary of Jingdezhen; Mayor of Jingdezhen; Secretary of Pingxiang; Secretary of Jiujiang; Vice Chairman of Jiangxi Province CPPCC; Deputy Director of Jiangxi Province People’s Congress of; Vice chairman of Jiangxi Province Federation of Trade Unions.

Table 8: Position in which illegal exchanges occurred.

The amount of bribes taken

The average sum taken in bribes in the 110 cases was 13.23 million yuan. The smallest sum involved was 22000 yuan, in the cases of Han Fucai and Zhang Xintai, sentenced respectively in 1991 and 1992, and the highest amount was 195.73 million yuan, in the case of Chen Tonghai, sentenced in 2010. We find that the average amount of bribes taken increased significantly between 1987 and 2015 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The average amount of bribes increased significantly between 1987 and 2015.

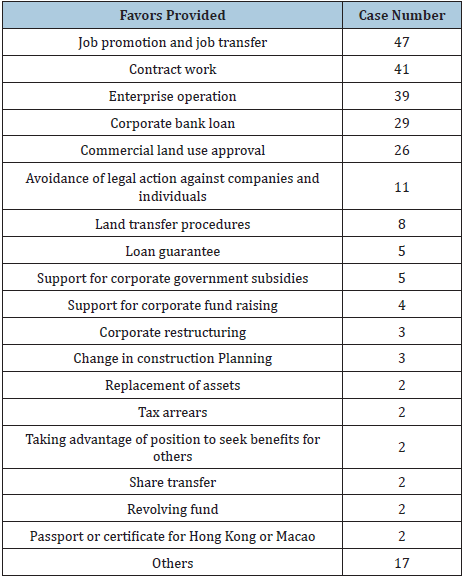

Favors provided in return for bribes

Bribery is an exchange of money for official power. In return for the bribe, officials gave favors to their bribers. Our analysis of 110 cases shows that more than 30 different types of favors were provided in return for bribe, mainly focusing on job promotion or transfers, contract work, enterprise operation, bank loans and corporate and individual avoidance of judicial accountability (Table 9).

Table 9: Favors provided in return for bribes.

Conclusion

The achievements of China's economic reforms and opening up over the last 30 years are obvious to all, but they have encouraged significant problems of corruption by senior party and government officials. This is one of the main reasons why the new Chinese Communist Party leadership (CCP) led by President Xi Jinping launched an anti-corruption campaign as soon as he took over as party chief at the end of 2012 (Liu [6]). Our study reveals that between 1987 and 2015 the number of officials convicted of corruption grew significantly and that sentences became more severe. In fact, since the beginning of this century, the Chinese ruling authorities have gradually increased the intensity of the fight against corruption. In addition to the weight of public opinion, the major reason is the risk that the evil of corruption in political and economic life could lead to the collapse of the regime.

China is a socialist country with a long history of bureaucratic culture Gong [3]. “Bureaucrats managing state assets, the sales of these assets and social development programs take advantage of such power to benefit themselves.” Chow [7]. As the party relies on bureaucracy to manage the centrally planned and hierarchically ordered economy, bureaucrats are becoming a powerful social class even though the party has placed many constraints on them Gong [3]. Our research reveals that the amount of bribery in China has increased steadily since 1987. In parallel with this trend, the average loss of social wealth in each corruption case has become more and more substantial Shuntian Yao [4].

The fact that the time span of corruption in China is increasing shows us that many senior officials have obtained promotion though hadden corruption (Dài bìng tíbá, Sick promoted) and that the senior official supervision mechanism is inadequate. Apart from in Tibet, corrupt officials are widely throughout China in every province, autonomous region and directly controlled city. This feature of corruption shows that the corruption of is not restricted to economically developed coastal areas or remote poverty-stricken areas.

Some corrupt officials hold important positions such as governor and mayor, while others hold what are considered in China as sinecures, such as heads of provincial and municipal People's Congress and CPPCC. Officials in the national ministries and in departments under the party central committee are just as corrupt as local corrupt officials. Similarly, judicial officials are just corrupt as those in charge of the allocation of the economic resources. Corruption in China seems to “have spread into the Party, into Government administration and into every part of society, including politics, economy, ideology and culture” Liang [1]. The result of our research confirms the views of Dong [2] that since launch of economic reforms, corruption has become even more widespread and exists at every level of China's political system.

Corrupt officials mostly use the traditional forms of exchange of interests. In other words, in the context of an imperfect system of legal supervision and a shortage of economic resources, officials use their power to help enterprises or individuals with problems such as promotion and job transfer, commercial land use rights, work contracts, bank loans and corporate operations in exchange for cash. The facts tell us that rent seeking is one of the most common sources of corruption in today's China Ngo [8]. Despite of the introduction of severe punishments and tough measures against corruption have been introduced by the party and the regime, “China has not really achieved its goal of anti-corruption” Dai [9], and “it still has a long way to go before success can be achieved “Guo [5]. If China wants to win the battle against corruption, it must above all enhance people's awareness of the law Chow [7] and establish a system of democracy.

References

- Liang G (1994) The practical encyclopedia of anti-corruption in China and foreign countries. China.

- Dong B, Torgler B (2013) Causes of corruption: Evidence from China. China Economic Review 26(1): 152-169.

- Gong T (1994) The politics of corruption in contemporary China: An analysis of policy outcomes. China, p. 15.

- Yao S (2002) Privilege and corruption: The problems of China's socialist market economy. American Journal of Economics and Sociology 61(1): 279-299.

- Guo Y, Li SF (2015) Anti-corruption measures in China: Suggestions for reforms. Asian Education and Development Studies 4(1): 7-23.

- Liu E (2016) A historical review of the control of corruption on economic crime in China. Journal of Financial Crime 23(1): 4-21.

- Chow GC (2006) Corruption and China's economic reform in the early 21st International Journal of Business 11(3): 265-282.

- Ngo TW (2008) Rent-seeking and economic governance in the structural nexus of corruption in China. Crime Law and Social Change 49(1): 27-44.

- Dai CZ (2010) Corruption and anti-corruption in China: Challenges and countermeasures. Journal of International Business Ethics 3(2): 58-71.

© 2020 Huai Yuan Han. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)