- Submissions

Full Text

Strategies in Accounting and Management

Ecological Governance and the Independent Assurance of Sustainability Reporting by Chinese Listed Companies

John Margerison1*, Jinghua Liao2 and Hongtao Shen3

1Department of Accounting and Finance, De Montfort University, UK

2School of Accounting, Guandong University of Finance, China

3Management School, Jinan University, China

*Corresponding author: John Margerison, Department of Accounting and Finance, De Montfort University, UK

Submission: January 27, 2020; Published: February 11, 2020

ISSN:2770-6648Volume1 Issue3

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to examine independent assurance of sustainability reports in a major emerging economy - China. It draws on a theory of ecological governance which offers models, one of which China’s governance model appears to fit. Desk based research has been used to establish the takeup of independent assurance by all Chinese listed companies from 2003 to 2015. The findings are that the take-up of independent assurance by Chinese listed companies has been very low and was falling in 2015. Companies using independent assurance do not fit into the typical types identified by previous Western research and are dominated by financial companies. The key explanation for the low take-up is that Chinese governance based on ecological authoritarianism exercised by the government has little need for public exercises in legitimation such as independent assurance. The practical implications are that through understanding of governance mechanisms in an authoritarian model such as China’s this leads to understanding about a different approach to ecological governance. The paper is original in that it looks at independent assurance in China from a new perspective with emphasis on absence of such assurance, rather than statistical analysis of determinants.

Keywords: Sustainability; Independent assurance; Ecological governance

Introduction

Independent assurance (IA) of sustainability reports by companies has grown worldwide over the last 15 years. There is evidence of the continuous growth in assurance by the world’s biggest companies since 2005 (2005 - 30% and 2015 - 63% coverage by G250 firms [1]. This phenomenon has been examined by a number of authors (see Section 2 below) and has been explained using theories such as institutional theory, stakeholder theory and legitimacy theory. However, critical research to date has stated that sustainability assurance practice fails to introduce the necessary countervailing power to ‘hold to account’ and therefore fails to enhance stakeholder accountability Cooper & Owen [2]. This observation leads to the suggestion that IA and the reporting (that it apparently offers credibility to) are no more than a part of the marketing and reputational management activities of large international companies. The imperative for change in China is much greater than in the West. China has happily invited the West’s environmentally sensitive manufacturing industries to set up in its territory and at the same time has fuelled its rapid economic growth from coal - the dirtiest fossil fuel. Hence in many parts of China (and the countryside is not exempt) the air is so polluted as to seriously threaten human health (evidence of the growth of respiratory diseases) [3]. This article seeks to examine IA in a Chinese context. The core aim is to establish whether IA is a necessary part of China’s system of ecological governance. The overall research question is: in a Chinese setting how can the take-up of independent assurance of sustainability reporting be explained? It does this by firstly examining the CSR reports of all Chinese listed companies from 2007 to 2015 and graphically representing the findings of CSR reporting and its assurance; secondly it examines the theoretical contribution by Jennings [4] on ecological governance and compares his model of authoritarian governance with the Chinese model developed since 2006; finally it uses the theoretical contribution to help explain the take-up of IA in China.

In summary the results are that after some increase in IA from 2007 to 2012 there has been a slight decrease to 2015 with only 1.3% (40) of Chinese listed companies using IA when 25.9% of companies have some form of CSR report. Only the financial industry has a large take-up (14 out of 58 companies =24.1%). Utilities have the next biggest take-up (7 out of 101 companies =7%). The remaining take-up is spread thinly across the other industry types. We think that this represents to a large extent an absence of IA in Chinese listed companies (11 industries have no IA whatsoever - representing 17.3% of all Chinese listed companies). The key aim is to examine China’s system of ecological governance and to ask why there is an absence of independent assurance of CSR reports in this system. In earlier literature absence of IA has been examined in particular in the USA but this is the first time that a very large emerging economy has been looked at in this way. There has been a tendency to analyse what is there, but we argue that where take-up is as low as in China such analysis achieves little.

It should be noted that it is assumed that sustainability reporting forms part of CSR reports used for the analysis in this paper. This assumption is based on a desk review of the Chinese assured CSR reports in 2015 that have been used in this research that has shown them all to have included references to social and environmental matters and this is considered typical of these reports generally. No further attempt to analyse content or quality is made in this paper as the emphasis is on the take-up of any kind of IA of CSR reporting and an explanation of the take-up and its general absence. Independent assurance of CSR reports refers to the evaluation, comment, appraisal, certification on the CSR reports’ form, content and authenticity by a third party, typically evidenced in China by an: Examination Report; Inspection Declaration; Verification Statement; Third Party Evaluation; Third Party Certification; or, Assurance Report.

In China the system of ecological governance that we concentrate on is that developed since the 2006 moves towards an ecological civilization [5,6]. Such a change required organizations (including companies) to be “accountable” for their implementation of the policy on the ground. This accountability is discussed in terms of the model of ecological governance in place in China. We describe the Chinese model of ecological governance as being the “visible hand” system, as opposed to Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” of the market. The Chinese government is providing public goods or services (such as environmental protection policies or actions) as an effective way to advance sustainability (with an emphasis on environmental issues). This is demonstrated on a policy level since 2006 with moves towards ecological civilization [6-8] and reiterated recently as the goal of “building a beautiful China” which was put forward by President Xi in the Nineteenth National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) held in October 2017.

In practical terms 2008 saw the elevation of the Environmental Protection Agency to full ministry status as the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP). This ministry is built around a network of offices at provincial and local levels. The provincial offices of MEP have been evidenced to publicly report on ecological matters for the whole province - a sense of provincial accountability. They also have been seen sharing responsibility for environmental problems with big companies in the province in addition to providing regulatory sanctions. By way of further examples: (1) based on a government initiative a carbon emission trading scheme (ETS) has been on trial for some companies since 2013 in seven cities, and it was launched nationwide in 2018; (2) in May 2014, the MEP issued an Interim Measure about arranging talks to officials of local government and related departments regarding environmental pollution problems and environmental protection issues. This is a measure to supervise how local governments strictly execute environmental laws and regulations; (3) on 28 November 2017 the Chinese central government published The Regulation on Off-Office Auditing of Officials on the Natural Resources Assets (Trial). This measure puts pressure on officials to protect natural resources and implement environmental protection laws and regulations. The first of these measures (ETS) is directly acting on companies, while the second and the third are directly influencing the governmental officials. Whether the pressure on the officials can be distributed or even transferred to the enterprises is critical to the effectiveness of these measures and provides an avenue for further research.

In this system of regulation and initiatives from government all companies must report to the local MEP on environmental indicators each year. As a result the MEP levies charges on the companies according to their emission levels. Further, the local MEP officials visit each company in their area every year and makes spot checks on environmental emissions and measuring devices. Sanctions by the MEP range from fines, to temporary closures, to permanent closures of firms. Much of the above model has referred to environmental matters. This article tends towards the ecological/environmental. However the governance of social and economic matters is also subject to the “visible hand” approach. Recent examples are: (1) in 2017 the China Securities Regulatory Commission has developed a more stringent attitude and measures towards Initial Public Offerings (IPO), which has resulted in a drastic decrease in the number of IPOs so as to avoid over-heating the economy and stock market bubbles; (2) in 2017, the government revised the Labour Law of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) which further protects employees’ legal rights and interests. Examination of the governance of the social and economic parts of sustainability present another opportunity for further research. To summarize - the contributions in this paper are: an examination of independent assurance in a Chinese context; the use of theory around ecological governance to explain the take-up of independent assurance by Chinese listed companies. It is hoped that this paper will add to the debate on the nature of governance and the forms of governance that are likely to lead to serious ecological improvements on the planet. The next section reviews key literature relevant to the research question.

Literature and Theoretical Insights

Sustainability accountability

The key theoretical explanations for sustainability accountability (both reporting and assurance) that have been identified in the literature linked to legitimacy theory, together with stakeholder theory and institutional theory [9-14]. These theories have predominated as they concentrate on explaining the reasons for external reporting of social and environmental accounting (SEA) data by companies. Such theorising has been criticized [15] with calls being made to open up SEA research to a broader range of theoretical perspectives.

CSR reporting and independent assurance

In the 20th Century audit (or attestation or assurance) was developed to give credibility to first financial statements and then many other areas of corporate activities (including sustainability reporting) [16-19]. As Power argued: “the audit looks more like the collusive production of comfort for an anxious society, a society that gets the empty ritualistic auditing it deserves [18].” Critical research to date on IA Cooper & Owen [19] has demonstrated a healthy academic critique of all forms of audit or assurance and certainly there is plenty of anecdotal evidence of audit failing to hold to account (see for example Cornish & Brown [20]. In publicized cases where auditors are fined for failing in their audit duties there is apparent regulatory oversight, but are those publicized cases the tip of an iceberg?

There has been significant, recent academic interest in the independent assurance of corporate social responsibility reporting by companies globally (including China) [21-45]. This research was preceded by work looking at environmental audit [46,47] and more general work looking at the explosion of audit in the 1980s and 90s (including environmental audit) [16-18,48]. A common theme on independent assurance has been the giving of credibility to the contents in CSR reports. KPMG since 2005 has explored the trends of independent assurance [1]. Guidelines for IA have been published by international and national organizations, including: the AA1000 Assurance Standard; the International Standard on Assurance Engagements (ISAE) 3000; and, the Global Reporting Initiative GRI. In academic research, an emerging strand of literature has also paid attention to the determinants of IA [33-37] and the quality of assured CSR information disclosure [38-40]. This paper does not seek to review all these contributions in detail - rather to tease out contributions on: why take-up of IA has been slow, particularly in the USA, and those that develop themes around IA’s role in governance. In terms of the USA and its low take-up of IA, Casey & Grenier [35] state: “..the level of assurance significantly lags international levels….Results shed light on this enigma by demonstrating that, unlike their international counterparts, U.S. finance and utilities firms are not more likely (than firms in other industries) to obtain CSR assurance despite facing significant social and environmental risks. As these industries are highly regulated in the United States, regulatory oversight may be acting as a substitute for CSR assurance. We also find that highly leveraged firms are less likely to obtain CSR assurance, potentially due to stringent bank monitoring indirectly suppressing demand.” Their conclusion is that intense regulatory oversight appears to act as a substitute form of credibility enhancement (as opposed to IA). This is supported by Kolk & Perego [41] who found that IA was positively associated with countries with weaker enforcement mechanisms. They further suggested that the USA’s low take-up of IA could be a result of the litigious tradition that has put off the potentially big providers (audit firms primarily) from marketing this service aggressively.

Adding to this analysis Birkey et al. [25] noted that: “Several recent studies focus more exclusively on CSR report assurance in the U.S. as this is a market where the practice is less common compared to the international context…” and on page 151 “…we examine only U.S. companies, and as such, we cannot generalize our findings to firms in other countries. This is potentially relevant given the U.S.’s classification as being more shareholder-oriented as opposed to stakeholder-oriented. Whether assurance on CSR reports in more stakeholder-oriented domains similarly appears to induce impacts regarding environmental reputation could potentially make for an interesting extension of our study.” That the USA appears to be idiosyncratic in the IA market is clear. As yet there has been no definitive study that explains and proves the situation in the USA In terms of IA’s role in a system of ecological governance, the evidence from research to date would suggest that IA is a corporate add-on to the CSR reporting that is seen to enhance credibility and reputation in the eyes of stakeholders. This has been termed managerial capture of the IA agenda (and the whole sustainability reporting agenda [47]. In most cases the IA has been carried out voluntarily with some exceptions where statutory requirements have been made (e.g. France). The types of firms likely to engage with IA are (1) big firms (2) more profitable firms (3) with lower leverage (4) have CSR strengths and concerns (5) have higher prior year cost of capital (6) be in more litigious industries (7) be more likely to voluntarily disclose information, and (7) have greater customer awareness (Casey and Grenier 2014). Casey and Grenier (2014) conclude that there appear to be economic benefits to firms from IA in terms of lower cost of capital and lower analyst forecast errors. This is considered by us to be a dangerous conclusion in that firms with the characteristics (1)-(7) above are likely to be better performing regardless of their engagement with IA. Whether this corporate response to sustainability (reporting and IA) represents a model of ecological governance that is likely to lead to a habitable, resilient and thriving Earth in the future is very doubtful. In Jennings [4] he argued that interest group democracy that exists in the West leads for a form of “negative governance” and this is the model that was illustrated by the Scandal [49]. Into this negative mix come governments and this article makes no attempt to systematically review Western governments and their role in ecological governance.

Theoretical contributions on ecological governance

Jennings [4] provided a useful definition and set of ideas about governance: “Governance is the overall process of coordinating, shaping, and directing individual and collective agency. Governance is inherently normative and value laden. It sets parameters around the means and form of human agency. Governance defines the telos, the ends, of collective agency; it stipulates worthy ideals, places parameters around objectives to be intended and sought, and excludes some types of objectives as wasteful and unworthy. Finally, governance embodies the character of collectivity, representing the kind of society an association of peoples aspires to be or become.” In the context of this article this suggests that governance is a complex interaction between governments and their people, the economy [embodied by organizations such as companies], civil society, and religious and cultural institutions.

Jennings [4] has developed ideas about “ecological governance” in which he is critical of the market-based models: “A parallel question concerns the relationship of the private and public sector in ecological governance. Starting from our current institutional formation of the state and market, can we evolve into something closely resembling the classical notions of polity and household (polis and oikos)? Many tend to think of the market as an autonomously operating, impersonal “system” or structure that needs no intentional agency of governance and no deliberately governing subjects. That is a fiction of conceptual and mathematical modeling and libertarian rhetoric Jennings [4].” This relationship between the private and public sector is a critical issue and one where, as we have seen, China has a particular set of governance arrangements. The market-based model he describes as “interest group democracy” which “is concerned with the aggregation and accommodation of interests among individuals and groups in societies where religious differences, ideological diversity, social competition, and conflict are widespread Jennings [4].” He argued that interest group democracy is “a kind of negative system of governance” that “makes a win-win type of growth scenario very attractive…It is prone to incrementalism and bias in favor of preserving the status quo Jennings [4].” It is our contention that what Jennings describes as the status quo in the West is dominated by corporations. Democratic “interest group” government policy based around economic growth is beholden to the wishes of corporations whose main objective is to grow and to increase market or shareholder value. Hence the purpose of modern corporate governance is to enable that main objective. Any attempts to report on sustainability matters are to enhance and secure reputation [50] in the face of risk of potential scandals (examples are Primark [51] and BP [52] in recent years). It is this “corporate” part of the governance matrix that has dominated and hence the model of ecological governance in interest group democracy is seen to be this corporate element with its triple bottom line reporting [53], where the traditional accounting reports have a pre-eminence in the financial market-dominated system. Jennings has proposed three varieties of ecological governance that could provide positive models of governance: “ecological authoritarianism”; “ecological discursive democracy”; and, “ecological constitutionalism”. He summarises “ecological authoritarianism” as meaning that: “successful governance in an ecological era will require centralized, elitist, and technocratic management at least in the areas of economic and environmental policy Jennings [4]”. It is possible that the current model of governance in China fits this variety of governance. This theme will be developed in the discussion section when appropriate models for China are discussed.

The description of “ecological discursive democracy” presents an idealized governance with the institutionalization and participatory empowerment and discourse within a diverse and pluralistic society Jennings [4]. Jennings himself admits that the normal institutionalized patterns of global capitalism, such as sharply rising inequality in the distribution of wealth and income, present a perfect democratic storm wherein “it is least likely that democratic governance, especially discursive democratic governance, will be able to respond” Jennings [4].

His third variety - “ecological constitutionalism” - is also a democratic form of governance which “involves building new ecologically oriented norms and values into the constitutional structure…the creation of several elite governing entities that can check and balance the more representative institutions. Jennings [4]”. The same perfect democratic storm mentioned above limits this variety of ecological governance in that it also has an instability that could lead to a transformational leader emerging and a slippage into ecological monism Jennings [4]. By monism we interpret Jennings to mean a reductionism by the leader and possibly a move towards an authoritarian model. He readily includes in his thesis both ecological resilience and social justice Jennings [4]. To that extent his varieties of ecological governance could lead to the sort of thriving world beyond survival that Bonneuil & Fressoz [54] have proposed. In particular the China focus of this article makes the ecological authoritarian governance variety very interesting.

A brief introduction to CSR reporting and assurance in China and related research

The first CSR report in China was called 2001 Health, Safety and Environment Report published by Petro China. All CSR reports were voluntarily disclosed until 2008. Since December 2008, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) has required that three types of public firms listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SSE) should disclose CSR reports. They are: sample firms in the SSE Corporate Governance Index; firms listed overseas; and, listed firms in the financial industry. At the same time, CSRC has also required the public firms listed in the 100 index of Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE) to issue CSR reports.

In November 2011, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC) convened a meeting which paid attention to the social responsibility of the central state-owned enterprises. At this meeting, all central state-owned enterprises were told to publish CSR reports within three years. Due to these mandatory requirements on CSR disclosure, the number of CSR reports has increased rapidly. In China by 2015, more than 5,500 CSR reports were released of which 1,087 were prepared by publicly listed companies (based on our findings below). The first assured CSR report in China was published in 2006 by China COSCO Shipping Corporation, and the assurer was DNV. Up to date, where carried out, the assurance of CSR reports has been voluntarily adopted. Research on CSR assurance published in Chinese [55,23] has been translated for the purposes of this paper.

Chen & Shen [55] carried out a comprehensive analysis of 467 assured CSR reports issued from 2010 to 2013 and found that the number of such reports had increased, with their quality gradually improving as assurance standards converged with international standards. They also commented on the low proportion of assured CSR reports to all CSR reports. Low quality of IA was commented on and was attributed to the low market share of professional assurance providers. Shen, Chen & Huang [23] used institutional theory as an explanatory theory and a methodology of event history analysis. Using an empirical analysis of Chinese listed firms from 2003 to 2013 they tested hypotheses around regulatory/coercive mechanisms leading to “involuntary” adoption. The regulatory/coercive mechanisms were noted as being weak due to the lack of government regulation of IA. However, since 2008, regulation of environmental disclosures has been implemented by government, stock exchanges and industry associations in China [56] suggesting that firms subject to greater regulation have been more likely to embrace IA. The cognitive/mimetic mechanisms were also noted as being weak except in certain industries such as the finance industry where leading firms embracing IA could have led to the embracing of IA by other competitor firms.

Another interesting finding was that most of the firms disclosing a CSR report with assurance were the large state-owned enterprises normally listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange. In another paper Shen, Wu & Chand [24] sought to evaluate the impact of social responsibility assurance on Chinese investor decisions. They used an experimental method with business school students used as a proxy for non-professional investors Shen, Wu & Chand [24]. Their results indicated that: “…CSR assurance increases investor willingness to invest and that the credibility of CSR information partially mediates the relationship between assurance and investment decisions Shen, Wu & Chand [24].” Whether or not it can be inferred that this could lead to a demand for IA by investors is uncertain. However the recent regulatory activities by the China Securities Regulatory Commission outlined above would tend to support the argument that there is an investor demand.

Methods

Much governance research has been based on statistical association/correlation/multivariate methods that usually attempt to find relationships between governance (based on proxies) and corporate economic performance or another variable such as board characteristics [57]. Contrary to this, the research on which this paper is based uses simple descriptive statistical analysis of CSR reports and independent assurance thereof. Using a very large data set of assurance reports of Chinese listed A share firms since the beginning of assurance practice in 2007 to 2015 (data source: CSMAR Database and collected by the authors manually from firms’ official websites, www.cninfo.com.cn, and http:// www.sustainabilityreport.cn). Firstly, we downloaded all of the CSR reports issued by listed A share firms available on the three platforms mentioned above. If reports were attached with at least an assurance report, then this report was regarded as an assured report. In total, the number of observations (assured CSR reports) is 282 firm-year (63 listed firms). We also seek to look at the demographics of reporting (which organizations participate and in which industries). However, this is secondary to the use of theoretical explanations based around ecological governance to explain the generally very low take-up of IA by listed companies in China.

Findings and Analysis

CSR reports and assurance practice across all Chinese listed companies

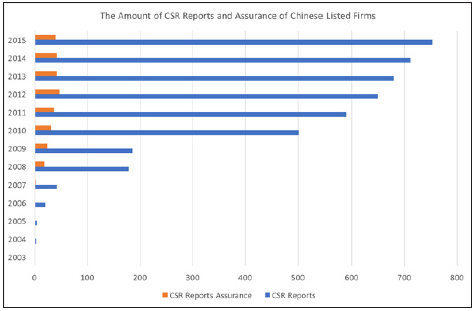

Figure 1: Graph showing the total CSR reports issued by Chinese listed firms 2003-2015 together with the total number of assured reports

(Source: The authors’ own desk-based research [see methods section])

The interesting observation from (Figure 1) is that whilst the number of CSR reports has steadily increased, the number of assured reports increased until 2012 and since then has slightly decreased. So assurance is not being taken up by Chinese listed firms in the way that the world’s biggest companies have taken it up. Also the assured reports have become an ever deceasing percentage of total reports (13% in 2008, 5% in 2015). This compares with 63% of the world’s biggest companies by 2015 in KPMG [1].

CSR reports and assurance practice by industry

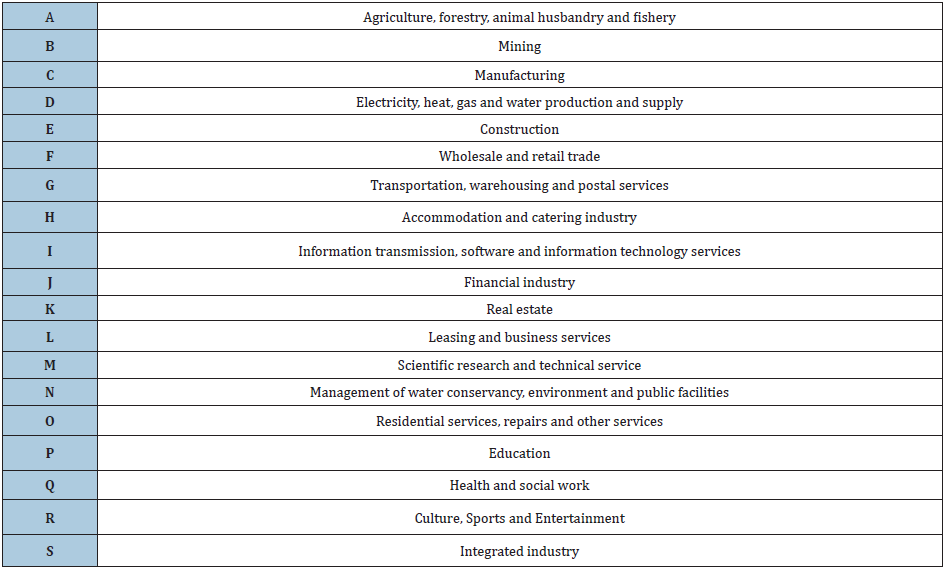

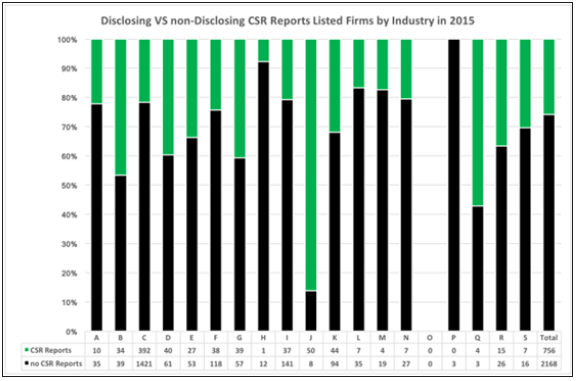

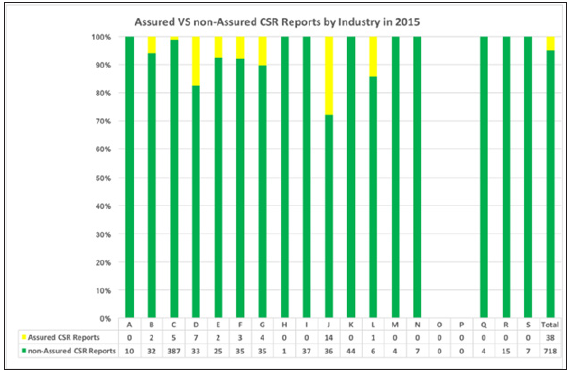

Listed firms on the Chinese Mainland are classified into 19 industries according to the classification guideline issued by China Securities Regulatory Commission in 2012 (Table 1 below). The number of listed firms in manufacturing industry (C) is the highest (1,421 in 2015), while there is no listed firm classified as residential services, repairs and other services industry (O). Industry categories translated from CSRC industry classification guideline 2012 Figure 2 shows that highest proportion of listed firms from the financial industry (J) disclosed CSR reports in 2015. However, every listed firm from the financial industry should have issued stand-alone CSR reports since 2008 because of the relevant mandatory requirement from CSRC. There are still some financial firms that have not followed the regulation and they appear not to have suffered any formal sanctions. The industries that have the second and third most CSR reports are health and social work industry (Q) and the mining industry (B). Regarding those industries that had the least amount of CSR reports in 2015, there were still no CSR reports prepared by listed firms from the education industry (P). Besides, only one firm from the accommodation and catering industry (H) published a CSR report. Less than 20% of listed firms from leasing and business services industry (L) and scientific research and technical service industry (M) released CSR reports. As a whole, slightly more than one quarter of listed firms prepared and disclosed stand-alone CSR reports. Figure 3 shows that a small proportion of listed firms from nine out of seventeen industries voluntarily had their CSR reports assured. The financial industry (J) had the highest proportion of listed firms issuing assured CSR reports, followed by the electricity, heat, gas and water production and supply industry (D) and then leasing and business services industry (L). Even though the number of CSR reports within manufacturing industry (C) is the highest in 2015, its percentage of assured CSR reports is the lowest. The percentage of listed firms having CSR reports assured is less than 10% in the mining industry (B), the construction industry (E), and the wholesale and retail trade industry (F). In total, among all listed firms which published CSR reports in 2015, only approximately 5% of them had their CSR reports assured. Further to this, and by way of explanation of voluntary IA, it was noted that of the 40 companies with IA in 2015, 33 were required to have a CSR report (primarily companies from the financial industry). It is suggested that in a more regulated CSR environment firms are more likely to consider IA to accompany and strengthen their CSR reporting.

Table 1: CSRC industry groupings.

Figure 2: Graph showing listed firms which published CSR reports by industry in 2015 compared with total number of listed firms in each industry in percentage terms.

Data source: China Stock Market & Accounting Research (hereafter CSMAR) Database.

Figure 3: Graph showing listed firms in 2015 voluntarily having their CSR reports independently assured compared with the total number of CSR reports by industry in percentage terms.

Data source: CSMAR Database and collected by the authors manually from firms’ official websites, www.cninfo. com.cn, and http://www.sustainabilityreport.cn.

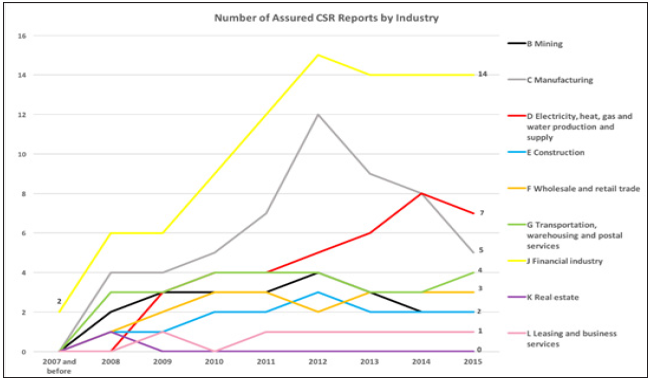

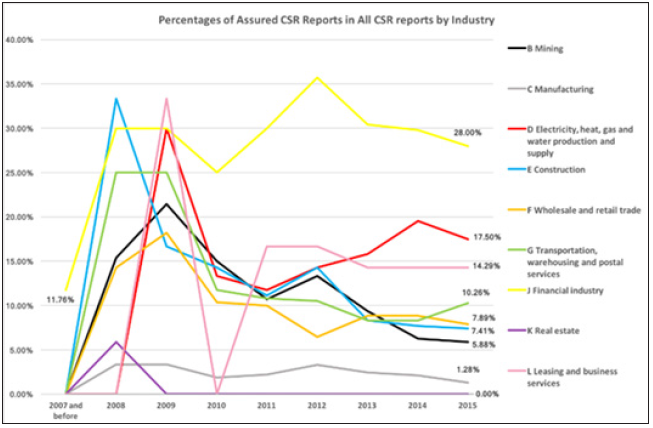

The trends in the quantity and the percentage of assured CSR reports in each industry are shown in Figure 4 & 5. In 2008, the number of assured CSR reports began to grow in nine industries. The highest growth rate was experienced in the financial industry (J), the manufacturing industry (C) and the electricity, heat, gas and water production and supply industry (D). But in each case this growth has decreased since 2012 and 2014 respectively. The numbers of assured CSR reports in other industries have fluctuated a little from 2008 to 2015. Although the numbers of assured CSR reports in most industries grew steadily from 2008, the percentages rose rapidly and then went down sharply from 2009 in all industries except in the financial industry where there was an increase in both CSR reports and assured CSR reports.

To summarize the findings, as the number of CSR reports by Chinese listed companies steadily increased from 2007 to 2015, there was a very low take-up of assurance and that this has shown a downward trend in percentage terms in all industries except for the financial industry where there is a stock market requirement to produce a CSR report. So, there is generally an absence of assurance of CSR reports (including their sustainability reporting content) in China. This is very much against the trend of the world’s biggest companies as surveyed by KPMG in 2015.

Figure 4: Graph showing the number of assured CSR reports by industry 2007-2015.

Data source: Collected by the authors manually from firms’ official websites, www.cninfo.com.cn, and http:// www.sustainabilityreport.cn.

Figure 5: Graph showing the percentage of assured CSR reports by industry compared to all CSR reports from 2007 to 2015.

Data source: CSMAR Database and collected by the author manually from firms’ official websites, www.cninfo. com.cn, and http;//www.sustainabilityreport.cn.

Discussion of the findings on Chinese listed companies’ CSR reporting and independent assurance

The first and most important finding is the very low take-up of IA of CSR reports by Chinese listed companies across the board when compared with studies looking at take-up internationally. The international studies such as KPMG [1] are not the best for comparative purposes with this research because they concentrate the world’s largest companies. However it is safe to conclude that IA in China is at a low level and that this needs some explanation. Going back to Jennings [4] and his mechanism for ecological governance called “ecological authoritarianism” as discussed in the literature review above: “centralized, elitist, and technocratic management at least in the areas of economic and environmental policy….rests ….on respect for authority, trust, prudence, and, sometimes, fear of penalty for failure to obey [4].” This model fits broadly with the Chinese political system and its moves towards ecological civilization. It is our contention that the Chinese model for ecological governance has a long term outlook and is able to provide stable leadership. This comes from the authoritarian power of the government. In such a system public accountability forms such as IA are much less relevant and hence the take up of IA is very low because of this. This is what is both new and important in this paper. The absence of both CSR reporting and its assurance in most Chinese listed companies suggests that sustainability assurance is not necessary in the Chinese system of ecological governance because the “visible hand” extended by government does not benefit from this exercise. This is because the systems of accountability to government are well developed and public statements by assurers are therefore largely a meaningless exercise. IA, where it takes place, is carried out by big international players (mainly former state owned enterprises that represent 45% of IA reporters in 2015) therefore improving the international standing of these Chinese firms. Another complementary explanation for “nonassurance” in a Chinese listed company setting is stimulated by [58] and his observations about “absence” in accounting. In this case the absence would be the general absence of IA. It is assumed that CSR/sustainability reporting and its IA are part of what is broadly considered to be accountability by firms. Choudhury stated: “The concern of the accounting researcher in studying organizations should be to understand and explain what is not happening as well as what is [58]”. In this study there is far more absence of IA than there is presence across Chinese listed companies. In Choudhury’s terms the absence could be explained in that it “not feasible”, “not necessary” or “not possible”. In this case we tend towards the “not necessary” in the sense already discussed, that public accountability is less important when ecological authoritarianism is being applied by government in China.

The second finding is that in percentage terms the financial industry (banking and financial services) is by far the most assured (35% of IA reporters in 2015). As it is not normally reckoned to be an environmentally contentious industry, it is unlikely that the assurance is in any serious way an attempt to give credibility to sustainability reporting - rather to give credibility to the internal governance mechanisms such as conduct of the board and relevant sub-committees such as risk and remuneration. Granted, environmental and social risk are dealt with in their reports, but these are not dominant themes in this industry. The industry with the next highest percentage take-up of IA is Electricity, heat, gas and water production and supply (17.5%). This is a very large group of disparate firms in terms of activities, but in general can be regarded as having high potential environmental impacts. However it needs to be noted that only 40% of firms in this industry produced a CSR report in 2015 and in terms of all firms only 7% have an assured CSR report.

Shen, Chen & Huang [23] have further suggested that the low take-up in riskier industries (in particular where there is high environmental risk) is the result of a low corporate regulatory environment in which firms seek to omit reporting and assurance of potentially adverse impacts (both social and environmental), so as not to alert public and other stakeholders to their unsatisfactory practices. The way in which IA coverage in percentage terms has fallen (see Figure 5 above) in recent years suggests that as more firms have reported on CSR, these firms have tended not to take up assurance in the same numbers. This is borne out by Shen, Chen & Huang [23] who found that the reporters with IA (or at least some form of assurance) tended to be the large listed state-owned enterprises. The industry classifications present some problems as the petroleum (oil and gas) industry is not separately classified. Gas is included in a separate group and the oil production industry is presumable incorporated into the mining classification. In many countries the petroleum industry creates big environmental impacts and consequently has been a model reporter with IA and this is not shown separately in the Chinese classification and so has not been examined in this research. This presents an opportunity for future research to drill down into the industry classifications.

Conclusion

The core aim was to establish whether IA is a necessary part of China’s system of ecological governance. This led to the research question: in a Chinese setting how can the take-up of independent assurance of sustainability reporting be explained? Our desk based research quickly ascertained that in 2015 the number of assured CSR reports decreased to a three year low of 40 from a total sample of 2,924 Chinese listed companies, 1.3% of the total. Even taking the companies with CSR reports (756) only 5.0% of these were assured. In these circumstances, although we have examined the demographics of the assured companies we have steered clear of too much statistical analysis of the take-up - rather concentrating on the lack of take up or absence. Absence does not lend itself to regression analysis and our analysis is based instead on a careful examination of the Chinese model of ecological governance (concentrating on the role of government in this) and using this model to explain why IA is of low importance in a Chinese setting. The low take-up of IA by Chinese listed companies is at odds with larger firms internationally where there was a steady growth in the percentage of CSR reports being assured to 2015. Our survey included an analysis across industries that highlighted one industry - the financial industry - where there has been some growth in IA practice. This has been explained with reference to the more overt stock exchange regulatory pressures on CSR reporting in that industry.

To summarize, the Chinese model of ecological governance we title the “visible hand” system. It includes: strong, long-term, stable central government and policy; ministry level control over environmental matters (MEP) with reporting, influence and control at provincial and local level; shared responsibility between MEP and companies; environmental reporting to MEP by companies and regular visits with sanctions available and used; and, companies adopting public reporting of sustainability matters as part of their CSR reporting within their corporate governance systems based largely on stock market requirements. Overall this system or model equates strongly to the “ecological authoritarian” model which is characterized by: “centralized, elitist, and technocratic management at least in the areas of economic and environmental policy Jennings [4]” Recent research on independent assurance (IA) of corporate social responsibility reporting (including social, environmental and sustainability reporting) has been found to be extensive with contributions from many researchers looking at different countries. A much stressed benefit of IA has been to improve the credibility of corporate social responsibility disclosures. A variety of theoretical explanations have been used - stakeholder, legitimacy, institutional, reputational risk - in order to explain the development of IA. Typically research has sought to explain the growth of IA practice using statistical measures of association between variables such as the presence of a Chief Environmental Officer. In this paper the emphasis has been on papers that have attempted to explain low take-up of IA (mainly in the USA) and on its overall place in ecological governance. Existing research has found evidence that regulatory oversight in the USA has negated the need for IA and that it is mainly seen as a part of the existing corporate governance package by leading firms in the West. So, extended corporate governance is seen to be the Western model of ecological governance that Jennings [4] argued is based on the interest group democracy negative governance model. The absence of IA has further been explained using Choudhury [58] and notions of an accounting activity not being necessary. This fits with the ecological governance model described and adds to the explanation.

In conclusion, the important contribution of this paper is to develop thinking about ecological governance and accountability in a Chinese setting. The “visible hand” model of SG put forward is very different to the model prevalent in “interest group democracies” which is seen to be a negative model of governance. This Chinese model has little or no need for independent assurance of CSR reports in its systems of accountability. So this paper adds to the discussion on models of ecological governance and the role of independent assurance in such models. This discussion of accountability and ecological governance in China presents many opportunities for further research, several of which have been mentioned in the paper. To summarize these points: the examination of quality of independent assurance in China and the types of assurers; the exploration of a more sociologically informed analysis of reporters’ motivations via interviews or case studies; an examination of whether the pressure on the Chinese government officials can be distributed or even transferred to the enterprises (this links in to a more in depth examination of the Chinese model of ecological governance); to drill down into the Chinese industry classifications in this study so that existing research on legitimacy issues could be added to; and, additional examination of social and economic parts of sustainability accountability in China. Outside the Chinese context there is an opportunity for further research into models of ecological governance around the world.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Professor Michelon for discussing the paper and for attenders’ useful comments at the CSEAR International Symposium and the paper development workshop, University of St Andrews, 29-31 August 2017. Thanks also to the anonymous reviewers at SIAM for their helpful comments.

References

- KPMG (2016) Currents of change. The KPMG survey of corporate responsibility reporting 2015, UK.

- Cooper S, Owen DL (2014) Independent assurance of sustainability reports. In: Bebbington J, UInerman J, O'Dwyer B (Eds.), Sustainability Accounting and Accountability. Oxon, Routledge, UK.

- Economy, Elizabeth C (2010) The river runs black-The environmental challenge to China's future. (2nd edn), Ithaca and London, Cornell University Press, UK.

- Jennings B (2016) Ecological governance: towards a new social contract with the earth. University Press, Morgantown, West Virginia, USA.

- Jiang C (2013) Creating an ecological civilization.

- Tu Weiming (2013) Understanding ecological civilization: The Confucian way. Hangzhou International Congress, Culture: Key to Sustainable Development, Hangzhou, China.

- Ma J (2007) Ecological civilization is the way forward.

- Wang Z, He H, Fan M (2014) The ecological civilization debate in China-the role of ecological Marxism and constructive post-modernism. Monthly Review 66(6): 37-69.

- Cho CH, Patten DM (2007) The role of environmental disclosures as tools of legitimacy: A research note. Accounting, Organizations and Society 32(7-8): 639-647.

- Deegan C (2002) The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures - A theoretical foundation. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 15(3): 282-311.

- Holland L, Foo BY (2003) Differences in environmental reporting practices in the UK and the US: The legal and regulatory context. The British Accounting Review 35(1): 1-18.

- Wilmshurst TD, Frost GR (2000) Corporate environmental reporting; a test of legitimacy theory. Accounting Auditing and Accountability 13 (1): 10-26.

- Gonzalez LC (2007) Sustainability reporting: insights from noninstitutional theory. In: Unerman J, Bebbington J, O'Dwyer B, (Eds.), Sustainability Accounting and Accountability, Oxford, Routledge, UK, pp. 150-167.

- Higgins C, Larrinaga C (2014) Sustainability reporting: insights from institutional theory. In: Bebbington J, UInerman J, O’Dwyer B (Eds.), Sustainability Accounting and Accountability. Oxon, Routledge, UK, pp. 273-285.

- Gray RD, Adams C (2010) Some theories for social accounting? A review essay and a tentative pedagogic categorization of theorisations around social accounting. Advances in Environmental Accounting and Management 4: 1-54.

- Power M (1997) The audit society: Rituals of verification: OUP Oxford, Oxford, UK.

- Power M (2000) The audit society-Second thoughts. International Journal of Auditing 4(1): 111-119.

- Power M (2003) Evaluating the audit explosion. Law & policy 25(3): 185-202.

- Ball A, Owen DL, Gray R (2000) External transparency or internal capture? The role of third‐party statements in adding value to corporate environmental reports1. Business strategy and the environment 9(1): 1-23.

- Cornish C, Brown JM (2017) PwC fined record £5m for ‘misconduct’ in social housing group audit. Financial Times.

- Park J, Brorson T (2005) Experiences of and views on third-party assurance of corporate environmental and sustainability reports. Journal of Cleaner Production 13(10): 1095-1106.

- Perego P (2009) Causes and consequences of choosing different assurance providers: An international study of sustainability reporting. International Journal of Management 26(3): 412-425.

- Shen H, Chen T, Huang N (2016) Involuntary or Voluntary: An event history analysis of decision-making in corporate social responsibility report assurance. Chinese Journal of Accounting Research 3: 79-86.

- Shen H, Wu H, Chand P (2017) The impact of corporate social responsibility assurance on investor decisions: Chinese evidence. International Journal of Auditing 21(3): 271-287.

- Birkey RN, Michelon G, Patten DM, Sankara J (2016) Does assurance on CSR reporting enhance environmental reputation? An examination in the U.S. context. Accounting Forum 40(3): 143-152.

- Peters G, Romi A (2015) The association between sustainability governance characteristics and the assurance of corporate sustainability reports. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 34(1): 163-198.

- Ackers B (2017) The evolution of corporate social responsibility assurance- a longitudinal study. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 37(2): 97-117.

- Owen DL, O'Dwyer B (2004) Assurance statement quality in environmental, social and sustainability reporting: A critical evaluation of leading-edge practice. In: Matten D (Ed.), ICCSR Research Paper Series, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, England, UK.

- Owen DL (2007) Assurance practice in sustainability reporting. In: UInerman J, Bebbington J, O'Dwyer B (Eds.), Sustainability Accounting and Accountability. Oxford, Routledge, UK, pp. 168-183.

- Rhianon Edgley C, Jones MJ, Solomon JF (2010) Stakeholder inclusivity in social and environmental report assurance. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 23(4): 532-557.

- O'Dwyer B, Owen DL (2005) Assurance statement practice in environmental, social and sustainability reporting: A critical evaluation. British Accounting Review 37(2): 205-229.

- O’Dwyer B (2011) The case of sustainability assurance: Constructing a new assurance service. Contemporary Accounting Research 28(4): 1230-1266.

- Simnett R, Vanstraelen A, Chua WF (2009) Assurance on sustainability reports: An international comparison. The Accounting Review 84(3): 937-967.

- Bagnoli M, Watts SG (2017) Voluntary assurance of voluntary CSR disclosure. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 26(1): 205-230.

- Casey RJ, Grenier JH (2015) Understanding and contributing to the enigma of corporate social responsibility (CSR) assurance in the United States. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 34(1): 97-130.

- Sierra L, Zorio A, García‐Benau MA (2013) Sustainable development and assurance of corporate social responsibility reports published by Ibex‐35 companies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 20(6): 359-370.

- Zorio A, García-Benau MA, Sierra A (2013) Sustainability development and the quality of assurance reports: Empirical evidence. Business Strategy and the Environment 22(7): 484-500.

- Fonseca A (2010) How credible are mining corporations' sustainability reports? A critical analysis of external assurance under the requirements of the international council on mining and metals. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 17(6): 355-370.

- Moroney R, Windsor C, YT Aw (2012) Evidence of assurance enhancing the quality of voluntary environmental disclosures: an empirical analysis. Accounting & Finance 52(3): 903-939.

- Pflugrath G, Roebuck P, Simnett R (2011) Impact of assurance and assurer's professional affiliation on financial analysts assessment of credibility of corporate social responsibility information. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 30(3): 239-254.

- Kolk A, Perego P (2010) Determinants of the adoption of sustainability assurance statements: An international investigation. Business Strategy and the Environment 19(3): 182-198.

- Morimoto R, Ash J, Hope C (2005) Corporate social responsibility audit: From theory to practice. Journal of Business Ethics 62(4): 315-325.

- Manetti G, Becatti L (2009) Assurance services for sustainability reports: Standards and empirical evidence. Journal of Business Ethics 87: 289-298.

- Hodge K, Subramaniam N, Stewart J (2009) Assurance of sustainability reports: Impact on report users confidence and perceptions of information credibility. Australian Accounting Review 19(3): 178-194.

- Mock TJ, Strohm C, Swartz KM (2007) An examination of worldwide assured sustainability reporting. Australian Accounting Review 17(41): 67-77.

- Gray R, Collinson D (1991) Environmental audit: green gauge or whitewash? Managerial Auditing Journal 6(5): 17-25.

- Gray R (2010) Is accounting for sustainability actually accounting for sustainability and how would we know? An exploration of narratives of organizations and the planet. Accounting Organizations and Society 35(1): 47-62.

- Power M (1991) Auditing and environmental expertise: Between protest and professionalization. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 4(3).

- Hotten R (2015) Volkswagen: the scandal explained. BBC.

- Bebbington JC, Moneva JM (2008) Corporate social reporting and reputation risk management. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 21(3): 337-361.

- BBC (2008) Primark fires child worker firms.

- Telegraph (2017) BP oil spill: Five years after 'worst environmental disaster in US history, how bad was it really.

- Elkington J (2006) Governance for sustainability. Corporate governance: An International Review 14(6): 522-529.

- Bonneuil C, Fressoz JB (2017) The shock of the anthropocene: The Earth, history and us, Verso, London, UK.

- Chen T, Shen H (2015) An analysis of the latest developments in CSR assurance in China: based on data from 2010 to 2013. The Chinese Certified Public Accountant 5: 65-70.

- Noronha C, Cynthia MI, Guan JJ (2013) Corporate social responsibility reporting in China: an overview and comparison with major trends. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 20(1): 29-42.

- Liao L, Lin TP, Zhang Y (2016) Corporate board and corporate social responsibility assurance: Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics, Springer Science+ Business Media, Berlin, Germany.

- Choudhury N (1988) The seeking of accounting where it is not: Towards a theory of non-accounting in organizational settings. Accounting Organizations and Society 13(6): 549-557.

© 2020 John Margerison. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)