- Submissions

Full Text

Strategies in Accounting and Management

Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Italy and Challenges they Face

Camillo Manera and Grażyna Śmigielska*

Associate Professor, Poland

*Corresponding author: Grażyna Śmigielska, Associate Professor, Poland

Submission: December 17, 2019; Published: January 08, 2020

ISSN:2770-6648Volume1 Issue2

Abstract

The aim of the paper is to draw attention to the challenges faced by small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in contemporary economy. Analysis of secondary data from four European countries show their crucial role in economy. They are important especially in Italy where the location in industrial districts (ID) has contributed to their success for many years. Due to the diminishing role of the factors contributing to the success of Italian SMEs they face new challenges which were identified.

Introduction

SME is the acronym for small and medium sized enterprises. It is very difficult to provide a definition of SME since certain criteria have been used to define what SME stand for most especially according to the countries, sizes and sectors1. It should be stressed that these kinds of businesses arose as a result of entrepreneurial activities of individuals. A commonly accepted definition of SMEs in UE countries is enterprises which employ less than 250 people, whose annual revenue does not exceed 50 million Euro or whose the total balance sheet does not exceed 43 million Euro2. The importance of the SMEs in the world’s economy is not an unexplored topic and their strong impact on the countries’ economies is unanimously recognized3 . SMEs’ features such being:

A. Farmer of workers who are asked to develop intensively their skills,

B. Generators of innovation,

C. Adaptable to the market changes,

D. Contributors of an “healthy” competition in the markets,

E. Fundamental part of the value chain, cooperating with bigger enterprises to produce value,

F. Due to their intrinsic nature, efficient and innovators,

make of them one of the most important element of the world business ecosystem4.

The SMEs are the most commune form of business organization5 and all countries focus on their structures, behaviors, trends and - more in general - everything related to them. They play a fundamental role in the B2B market (Business to Business), which deeply drives the countries’ economies6 however, B2B market and SMEs together is an underrepresented topic among the literature contributions7. They have a deep impact on the economies and their importance is multidimensional:

Foot Note:1Lucky EO, Olusegun AI (2012) Is small and medium enterprises (SMEs) an entrepreneurship International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 2(1): 487-496.

2Verheugen G (2005) La nuova definizione di PMI. Guida dell’utente e modello di dichiarazione, European Commission, Pubblicazioni Della Direzione Generale Per Le Imprese E L’industria.

3Neagu C (2016) The importance and role of small and medium-sized businesses, Theoretical and Applied Economics, Volume XXIII, No. 3(608), pp. 331-338.

4Ibidem.

5Ndubisi NO, Matanda JM (2011) Industrial Marketing Strategy and B2B Management by SMEs. Industrial Marketing Management 40: 334-225.

6Cortez RM, Johnston JW (2017) The future of B2B marketing theory: A historical and prospective analysis. Industrial Marketing Management 66: 90-102.

A. Sociological, as SMEs constitute 90% of the enterprises and more than 60% of the employee worldwide , 99.8% of all companies in EU28 and 67% of all employee9.

B. Political, since SMEs constitute an important instrument of poverty reduction in the less developed countries10.

C. Economical, since they account for 50%-60% of GDP (Gross Domestic Product) in the most developed countries11 and constitute in Europe the 57,4% of added value in EU2812. Furthermore, it has been proved the positive correlation between the growth of the GDP per capita and the economical impact of the SMEs in a country13. While in the world, and in Europe too, SMEs play a fundamental role, “...in Italy, SMEs play an even more important role in the non-financial business economy than is average for the EU14”. They are the backbone of European economy as 99,8% of the European companies are classifiable as SMEs operating in non-financial sector; they generate 57% of the value added and employ 67% of the total employment15. The aim of the paper is to show the role of SMEs in Italian economy and identify challenges their face due to changes which take place in global economy. The analysis is based on secondary data, mainly retrieved on ISTAT, European Commission, Italian Districts Observatory, ICE Agency, Eurostat and European Central Bank.

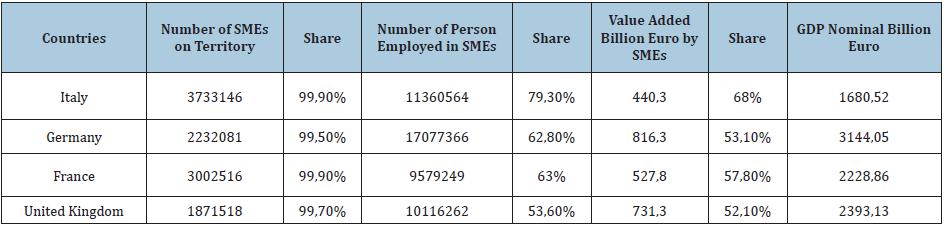

The role of SME in Italian economy

In Europe, over 90 million people are employed in SMEs16 and, with 3,733,146 SMEs, Italy is the country with the highest number of SMEs in non-financial business in Europe17, (see Table 1). In Table 1, the share of the SMEs compared to the total number of the enterprises is similar (Italy and France are much closed tough). However, the highest share of employed in SMEs was in Italy - 79,3%, and in UK it was just 53,6%, in 2016. Similarly, it is with the contribution to GDP; although in all analyzed countries it is more than 50%, in Italy it was the highest - 68% whereas in UK was the lowest - 52,1%. Data confirm that SMEs constitute the backbone of economies of the analyzed well-developed countries, and that they are more noticeable in Italy. These outcomes are highlighted more when compared to the incidence that large companies have on the economies of the related countries, showed in Table 2. In all the countries, the share of the large companies is less than 1%, which is impressively less than the “more than 99% presence” of the SMEs. Large companies employ just 20,7% of the total of the people working in companies in Italy, which is less than all the other countries in the table. In Italy, the added valued in percentage generated by large companies in non-financial business accounts for 32%, still less than the other countries. Besides, in Italy 46% of the employee work in micro enterprises (less than 9 people, see Table 2), which is the highest percentage in Europe; in EU28 the employee in micro companies account for 18% indeed18. Comparing the large enterprises’ impact and the SMEs’ impact on the related economies, strengthen the idea that Italian’s economy finds its roots in SMEs, even more than other mayor countries in Europe. On another hand, Europe “needs” Italian’s SMEs to be healthy. In Italy, SMEs are mainly concentrated in the North of the country, which is industrially developed, while the South is highly unemployed and underdeveloped19. Italian SMEs drive the Italian economy with manufacture of high-quality consumer goods, of which the majority is produced by private family companies20.

Table 1: SMEs’ presence in the territory and impact on the economy in 4 top countries per GDP in EU28.

Source: Own elaboration based on the data retrieved from Eurostat and SBE documents 2016 for Italy, Germany, France and UK.

Footnote:

7Ndubisi NO, Matanda JM, op.cit, 2011.

82Berisha G, Pula JS (2015) Defining Small and Medium Enterprises: a critical review. Academic Journal of Business, Administration, Law and Social Sciences, Vol 1, No1.

9Muller P, Devnani S, Julius J, Gagliardi D, Marzocchi C, op.cit, 2016.

10Ayyagari M, Beck T, Demirguc-Kunt A (2007) Small and medium enterprises across the globe. Small Business Economics 29(4): 415-434.

11Ibidem.

12Muller P, Devnani S, Julius J, Gagliardi D, Marzocchi C, op.cit, 2016.

13Beck T, Demiruc-Kunt A, Levine R (2005) SMEs, growth, and poverty: cross-country evidence. Journal of economic growth 10(3): 199-229.

14European Commission, “2016 SBA Fact Sheet Italy”, 2016.

Table 2: Large companies’ presence in the territory and impact on the economy in 4 top countries per GDP in EU28.

Source: Own elaboration based on the data retrieved from SBE documents 2016 for Italy, Germany, France and U.K.

Industrial districts as a main organizational form of SMEs in Italy

Italian’s economy has historically been strongly influenced by three major groups of enterprises:

a. Large Private companies (such Fiat, Ferrero, etc.)

b. Large Public companies (such Enel, Poste Italian, etc.)

c. Small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs), the most present in territory.

Group C is constituted by millions of companies spread in all the regions; when they happened to start up close to each other, they have been likely to begin a profitable relation and business cooperation that often evolved in business/industrial districts (IDs)21. The Italian Districts Observatory (OND), in the report of 2014, defined districts as the business “chains based on interdependence and cooperation relationships of among mostly SMEs, located in one particular territorial area”22 .

In its analysis, the OND divides the 141 Italian districts23 by categorizing the enterprises into two macro categories of chains:

A. Core business chains: part of the value chain composed by SMEs that are rooted in production of products that traditionally characterizes the land where they are located, and delivery of services strictly related to the value produced in their area.

B. Not core business chains: part of the value chain composed by SMEs that - directly or indirectly - supply the SMEs belonging to the first group24.

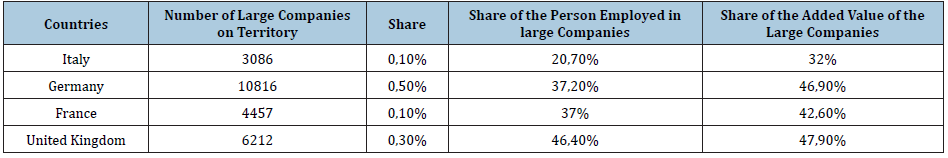

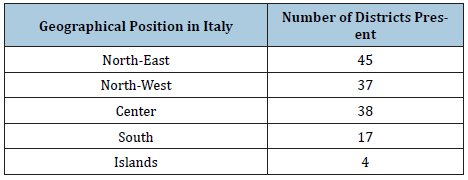

Figure 1: Distribution of the Italian districts in the country.

Foot Nonte:

15European Commission, “Annual Report On European SMEs, 2016/2017”, 2017. 16Muller P, Devnani S, Julius J, Gagliardi D, Marzocchi C, op.cit, 2016. 17European Commission, op.cit, 2016. 18Mondo PMI, “PMI Italian Ed Europe A Confront”, 2017. 19The World Factbook, “Introduction to Italy”. 20Ibidem. 21Mondo PMI, “PMI Italian Ed Europe A Confront”, 2017. 22Italian Districts Observatory, “Structure, evolutionary tendons and slump prospects of industrial districts”, National Observatory of Italian Districts - Report 2014. 23ISTAT, “The Industrial Districts”, February 24, 2015. 24Italian Districts Observatory, op.cit, 2014.

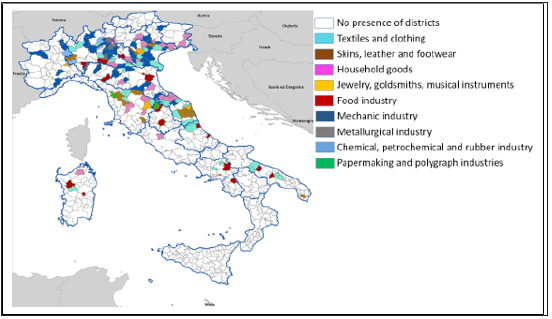

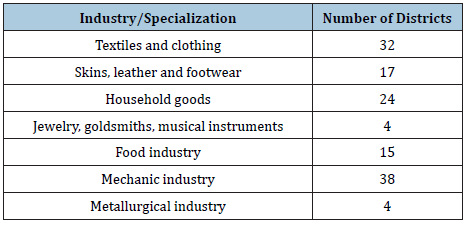

Therefore, the category A includes all the SMEs that presumably raised thanks to availability of raw materials in the land and developed a unique ability to transform them in products positioned in niche markets25. SMEs operate mainly in B2B market, while the SMEs belonging to category B operate, per definition, only in B2B market, finally composing the value chain. All the districts are divided by specialization as shown in Table 3. Most districts are involved in mechanic industry, while the second specialization per number of districts is textile and clothing. Because Italy is mainly industrialized in North, the largest number of districts is in the North area of the country26, as shown in Figure 1. While the districts cover a vast part of the country from the Center to the North, they are less in the South. Overall, 21 districts are in the South and in the Islands, less than the number of districts in the North-East area (45), which is the most industrialized, as shown in Table 4. Districts have naturally developed in Italy because the interaction of their members rises their competitiveness. Alfred Marshall described Industrial Districts as “[…] socio-economical entities, localized in a specific geographic area, in which the firms interact due to their high level of specialization”. They are independent of other business areas and, consequently, they preserve the successful business flow and passage of knowledge27. Districts benefits of the local resources, of the chance of running sharing investments in new expensive industrial machineries, and of the environment that enhances knowledge spillover. Italian economist Giacomo Bucatini described IDs as entities in a well-defined territory or geographical area, in which people and a population of firms are historically rooted and interact together successfully28. Geo-localization, people and firms are the main component of an industrial districts indeed. Scholars affirm that Italian districts started to exist as a union of workers concentrated in many small socio-economic organizations already in 1950s and they started to rise from 1960s29.

Different District’s assets constitute the precondition for their survival and growth of competitiveness over the time, regardless of the place where they are30:

1. The ability of the firms to transfer their knowledge to the other firms involved in the business chain31.

2. The dynamism of the firms and their ability to create reticular relationships32.

3. The high level of specialization, the flexibility and the ductility of the firms involved33.

Table 3: Distribution of the Italian Districts per industries and specialization.

Source: Own elaboration based on the Table retrieved from ISTAT “I Distretti Industriali”.

Table 4: Geographical location of the districts in Italy.

Source: Schilirò D, “Italian Industrial Districts: Theories, Profiles and Competitiveness”, 2017.

One of the most important factor of ID competitiveness is knowledge transfer. According to Marshall knowledge circulating in IDs is mainly tacit, rooted in practice and technical. Knowledge transfer is often an outcome of the long cooperation aimed at creating value in the market that SMEs have within the IDs. Cocreating value enhances SMEs to establish deep relationships. The deeper the relationships, the more the knowledge transfer is intense. Because of SMEs ‘cooperation in ID, they are able to face competition from international players34. The ability to interconnect and create reticular relationships in Italy allowed SMEs to keep craft models of production, in opposition to the Fordism trend in other foreign markets35. The outcome of these strong socioeconomic union models is defined as the “Made in Italy36, which become a valuable brand in the entire world. The importance of the Italian IDs is highlighted by the data provided by ISTAT; in 2015 they accounted for 24,5% of the country’s production system in terms of workers and 24,4% in terms of local production unit, while 22% of the Italian population (almost 5 million people) works in companies operating in IDs37.

25Cunningham CJL (2003) Family Matters: Challenges Facing Italy’s Smes And Industrial Districts, 2003, Contradictions and Challenges in 21st century Italy. 26Schiliro D (2017) Italian Industrial Districts: Theories, Profiles and competitiveness”, 2017, Management and Organizational Studies Vol. 4, No. 4. 27Ferrara M, Marilia R, op.cit, 2013. 28Bucatini G (2001) “The Marshallian Industrial District as a Socio-Economic Notion”, in Pyke F, Bucatini G, Sengenberger W, “Industrial Districts and Inter- Firm Cooperation in Italy, International Institute for Labor Studies”, in Alberti F, “The Governance of Industrial Districts: A Theoretical Footing Proposal”. Luis Papers, no. 82, Small and Medium Business Series. 29Dei Ottati G (2018) Marshallian Industrial Districts in Italy: the end of a model or adaptation to the global economy?”. Cambridge Journal of Economics 42(2): 259-284 30Swords J, “Michael Porter’s Cluster Theory as a local and regional development tool - the rise and fall of cluster policy in the UK”. Local Economy 28(4): 367-381. 31Rullani E (2004) La Fabbrica dell’Immateriale, Produrre valore con la Conoscenza. Carocci Editore Chapter 9-10 32Law J (2009) Actor Network Theory and Material Semiotics. The new Blackwell companion to social theory, 141-158. 33Musso F (2013) Strategie e Competitività Internazionale delle Piccole e Medie Imprese. Un’analisi sul settore della meccanica, CEDAM, Chapter 1, pg. 6

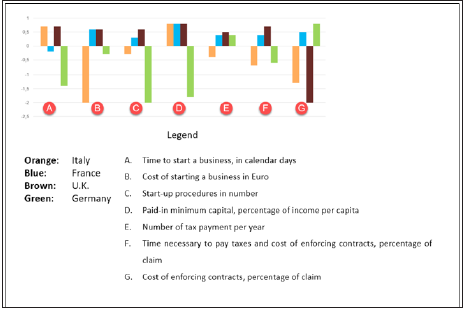

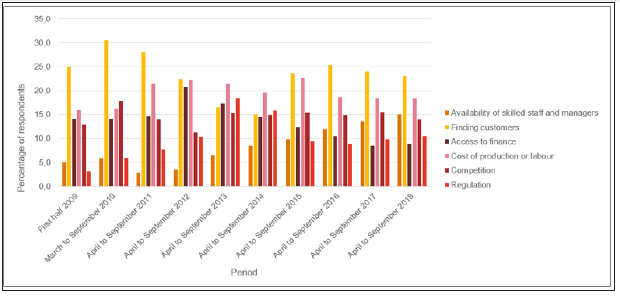

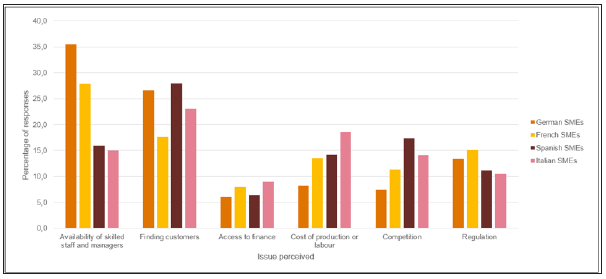

Challenges faced by the SMEs in Italy

The crisis particularly stroked the Italian Districts that naturally reduced their number in the territory since 200138. For instance, Prato, a well-known textile district, lost more than 50% of the companies39 due to the deep crisis of the country. Italy has been unable to help companies to overcome the crisis and to face global changes40. Between 2008 and 2013, 41% of the Italian companies closed, which corresponded to a reduction of 637,729 companies over the same period41. Italian’s SMEs are still facing many challenges and suffering some structural obstacles to their development, especially comparing with the major European economies. For instance, the European Union’s survey dedicated to the SMEs relieved that Italian SMEs suffer a Public Administration (PA) not able to incentive or satisfy their basic needs: Figure 2 shows that Italian’s SMEs perceive that Public Administration does not respond to their needs. It should be stressed that the cost of starting a new business (B) is the highest in Europe, discouraging startup businesses. The comparison with other European countries (France, UK and Germany) relieved that Italy is the second lowest performer in Europe regarding the Public Administration responsivity and Germany, however it is the actual European greatest economy, is the lowest performer42. Bureaucracy and taxes are still gapping the chances of the Italian’s SMEs to rise as they were before 2007; the number of taxes and the total time needed to pay them is negative and it is negatively overcome only by Germany. Nowadays due to the growth of the importance of the technologies in business sectors, some researches proved that the importance of the geo-localization of the firms has diminished, in parallel with the increasing in importance of the capacity of investments in technologies of these firms43. Also, globalization affects IDs in Italy. Roberta Rubellite analyzed Brenda’s district in which shoes producers are located44. The research showed that to survive they have accepted a functional downgrading, abandoning design and marketing and focusing on production. But the question is if they can survive the competition from lower labor costs countries like China. Technologies now have fundamental impact on the business. They allow the companies to reduce the costs of the moving, the time for communicating and the need of delocalization by interconnecting the companies, while empowering the transfer knowledge and the possibilities of feedback measurement. Therefore, SMEs, that historically suffer a lack of funds to invest and of margin that can protect themselves during a slowing down of the market45, when are forward-looking with technologies, get deep benefits from them. SAFE survey collects the European SMEs’ most perceived problems related to the market; the survey is conducted twice a year and the analysis reveals that since 2009 (year of the first available report) , the SMEs’ main perceived problems and challenges47,48 in all countries was to find new customers and skilled staffs as shown in Figure 3. Figure 3 evidences how SMEs historically perceived a lack of new customers as a threat for their business. The trend reveals that in 2018, 22,4% of the responding SMEs across the European countries are strongly keeping perceiving this issue as the main one. On the contrary, the issue related to the finding skilled staff49 grew till being the European SMEs’ most perceived issue of 2018 with 26% of respondents. The issue of finding skilled staff probably grew in parallel with the growth importance of technology adoption, pushing SMEs in selecting staff always more updated and experienced in business technologies. The other issues measured by the survey which are: “access to finance”, “cost of production or labor”, “competition” and “regulation” were perceived as a problem by less than 15% of the responding SMEs, evidencing a substantial difference between them and the abovementioned two most perceived issues. The above-mentioned European scenario should stress that finding customer is not a challenge only for Italian SMEs, but it is a shared perceived issue by all countries’ SMEs. In other words, the problems perceived are important in each country. This is shown by the analysis from the 2018. Figure 4 evidences few differences between major European countries that attended the SAFE survey. 23% of the Italian SMEs that took part in the survey, indicated “finding customer” as the main perceived issue, more important than the second most perceived issue related to the “cost of labor and production” that accounts for 18,5%.

Figure 2: SMEs’ perception on PA’s capability of being responsive to their needs.

Figure 3: European SMEs’ perceived problems (years 2009 - 2018).

Figure 4: The challenges faced by German, France, Spanish and Italian SMEs in 2018.

Summary

Development of new technologies and globalization of production have diminished the previous sources of small and medium sized enterprises’ competitiveness in Europe. This issue is especially hot in Italy where economic development of regions is related to the location of industrial districts. To keep the economy sound public administration should take some steps towards cutting red tape and reducing taxes. However to survive SMEs should look for the ways to keep existing and find new customers.

© 2019 Grażyna Śmigielska. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)