- Submissions

Full Text

Research in Pediatrics & Neonatology

Anxiety in Children: A Narrative Review

Tiffany Field*

University of Miami/Miller School of Medicine and Fielding Graduate University, USA

*Corresponding author: Tiffany Field, University of Miami/Miller School of Medicine and Fielding Graduate University, USA

Submission: May 15, 2024; Published: June 04, 2024

ISSN: 2577-9200 Volume8 Issue3

Abstract

The recent literature on anxiety in children suggests that prevalence rates have been highly variable, ranging from a low of 1% in China and 3% in the U.S. and Canada to a high of 17% in Turkey and 25% in Greece. This variability may relate to age range differences of the samples or to different measures of anxiety (symptoms versus diagnoses). Very few negative effects of anxiety have been addressed including increased sensory and emotion processing problems, difficulty managing social fears, body image dissatisfaction, sleep disturbances and the development of bipolar disorder. Predictors/risk factors have been the primary focus in this literature and have included parent variables of prenatal depression and elevated hair cortisol, parental anxiety and different parenting styles (permissiveness, overprotectiveness and harsh disciplinary style). The child variables have included negative emotionality, irritability and fearfulness. Other child variables include less social skill, problematic technology use, attention bias toward negative stimuli, negative expectations, reading and spelling problems and low academic achievement. The most effective intervention has been Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, although others have appeared in this literature including attention training, guided breathing and exercise. Potential underlying mechanisms for anxiety in children include prenatal anxiety, lack of vagal flexibility, low levels of brain derived neurotrophic factor and lower total cortical and amygdala volume as revealed by fMRIs. Although the data highlight the prevalence and severity of anxiety in children, they have been primarily based on parent-report surveys that have yielded mixed results across samples.

Introduction

Anxiety is one of the most common problems in children, ranging in severity from social anxiety to anxiety disorder. Different types of anxiety, for example, pre-operative, dental, test and weather anxiety, have also appeared in this literature as anxiety in different conditions like obesity, autism and cancer. This narrative review is focused on social anxiety and anxiety disorder and summarizes 52 papers that were derived from a search on PubMed and PsycINFO using the terms anxiety in children and the years 2023-2024. Exclusion criteria included case studies and non-English language papers. The publications can be categorized as prevalence data, negative effects of anxiety, predictors/risk factors for anxiety, interventions and potential underlying biological mechanisms. This review is accordingly divided into sections that correspond to those categories. Although some papers could be grouped in more than one category, 5 papers are focused on prevalence, 6 on negative effects of anxiety, 17 on predictors/risk factors, 17 on Interventions, and 7 on potential underlying biological mechanisms for anxiety in children.

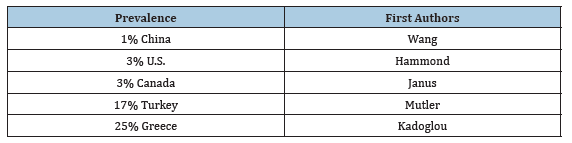

Prevalence of anxiety in children

The prevalence rates for anxiety in children have varied widely from a low of 1% in China and 3% in Canada and 3% in the U.S. to greater prevalence rates of 17% in Turkey and 25% in Greece (Table 1). This variability likely relates to potential cross-cultural differences, to different definitions of anxiety (mild to severe anxiety) and to the age range of the sample being assessed, with greater anxiety in older children and adolescents in those samples where both children and adolescents have been included.

Table 1:Prevalence of anxiety in children (and first authors).

The very low prevalence of 1% in China is likely related to anxiety being strictly defined as a DSM-IV diagnosis of anxiety disorder [1]. In the U.S. study on the adolescent brain cognitive development sample (N=9,353 nine-to-10-year-old children), 3% were known to have a current anxiety disorder [2]. A similar prevalence of 3% was noted in Canada, but on younger kindergarten children in a significantly larger sample (N=974,319) [3]. This similarly low prevalence in younger children and older children is likely related to the younger children being “highly anxious children”.

In the study from Turkey, a greater prevalence of 17% was noted in older 9-year-old children (N=5842) [4]. This relatively high prevalence rate was based on children who were not considered impaired. A lower prevalence of 5% was reported for children who were considered impaired, suggesting, again, that the difference in prevalence related to the severity of anxiety. A surprisingly very high prevalence of 25% was noted in Greece for borderline or clinical symptoms of anxiety in young preschool children (N=443) [5]. This high prevalence in this very young sample may relate to anxiety having been defined as borderline or clinical symptoms of anxiety rather than diagnosed anxiety disorder.

The differences in prevalence rates across these samples likely derive from the different age ranges assessed, with older children and adolescents more frequently having a diagnosed anxiety disorder. This age difference is further illustrated by a large, longitudinal database (N=445,449) on Portuguese youth showing that the mean anxiety levels increased from middle childhood through adolescence before stabilizing in adulthood [6]. These data highlight the need for more longitudinal studies on the prevalence of anxiety in children.

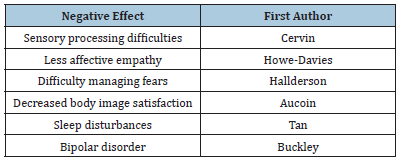

Negative effects of anxiety in children

Surprisingly few negative effects have been researched in this recent literature on anxiety in children (see Table 2). Those include sensory processing and emotional processing problems, difficulty managing social fears, body image dissatisfaction, sleep disturbances and the development of bipolar disorder.

Table 2:Negative effects of anxiety in children (and first authors).

In a study on sensory processing difficulties in children with anxiety disorder (N=82), all senses were affected [7]. In research on emotional and socio-cognitive processing in children with symptoms of anxiety (N=174 4-8-year-olds), the children were noted to have less affective empathy which led to more difficult social interactions [8].

A qualitative study has also highlighted the social problems that result from social anxiety disorder [9]. In this study, 12 children were interviewed (age 8-12 years) regarding their social experience during a social stress induction task. The themes of the interviews were discomfort being the center of attention, lack of awareness of cognitions and managing social fears.

Anxiety has also led to body image dissatisfaction in a longitudinal study from Canada (N=247 7-12-year-old children) [10]. In this sample, anxiety at time 1 led to body dissatisfaction at time 2. This occurred more frequently in older females and was considered a precursor to eating disorders.

The sleep problems of children with anxiety disorder have been relatively ignored in this literature. However, at least one research group has reported that children’s sleep disturbances continued to persist following treatment for anxiety disorder [11]. These findings highlight the need for further research on interventions for sleep problems of children experiencing anxiety [11].

One of the worst negative effects of child anxiety disorder is the risk for bipolar disorder. In a systematic review of 16 longitudinal studies, anxiety disorder was noted to be a risk factor for bipolar disorder in children [12]. This highlights the importance of early identification of anxiety disorder for the prevention of the potential development of bipolar disorder.

Negative effects could also be considered risk factors given the reciprocal nature or the comorbidity of problems like sleep disturbances and anxiety disorder [11]. Most of this research has been cross-sectional studies, precluding conclusions about directionality. This highlights the need for longitudinal studies, such as the longitudinal research suggesting, for example, that early anxiety disorder can precede later bipolar disorder in children [12].

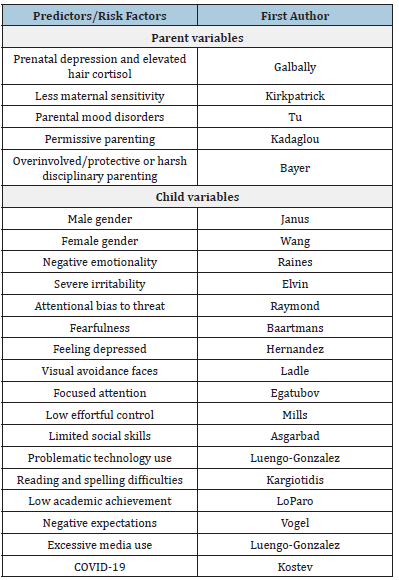

Predictors/risk factors for anxiety in children

The recent literature on anxiety in children has primarily focused on predictors/risk factors, which, as already mentioned, could also be considered effects given that most of the research is cross-sectional so that directionality cannot be determined. Whether researchers consider comorbid factors as negative effects or predictors/risk factors would seemingly be arbitrary and reflect the researcher’s primary interest/bias. Predictors/ risk factors that have appeared in the recent literature on anxiety in children have included variables that are based on their origins as parent or child variables (see Table 3). The parent variables include prenatal depression and elevated hair cortisol, maternal insensitivity, parents’ mood disorders and different parenting styles (permissiveness, overprotectiveness and harsh disciplinary style). The child variables have included negative emotionality, irritability and fearfulness. Other child variables are less social skill, attention bias toward negative stimuli, negative expectations, reading and spelling problems and low academic achievement.

Table 3:Predictors/risk factors for anxiety in children (and first authors).

Parent variables

The parent variables that have appeared in this literature include prenatal depression and elevated hair cortisol, maternal insensitivity, parents’ mood disorders and parenting styles including permissiveness, overprotectiveness and harsh discipline. In the study on prenatal depression, pregnant women were recruited during early pregnancy (N= 190) and followed until the children reached four years of age [13]. The assessments that were administered included the structured clinical interview for DSM disorders, the childhood trauma questionnaire, the parenting stress index and hair cortisol samples. Prenatal depression and elevated hair cortisol were early risk factors for later childhood anxiety disorder.

At least one research group who conducted a longitudinal study on maternal and child perceptions of child anxiety (N= 180 mother - child dyads from Canada) followed the dyads from preschool to middle childhood to early adolescence [14]. The researchers concluded that maternal awareness of their children’s anxiety in the presence of maternal insensitivity was the way in which anxiety was transferred from the mother to the child. In a systematic review and meta-analysis (N= 35 studies), however, the risks of anxiety disorders in offspring only occurred when parents experiencedmood disorders [15]. This was notable for all anxiety disorders, especially panic disorder. Both maternal insensitivity and parental mood disorders have been risk factors for other problems in childhood including sleep disorders [16] and depression [16].

A variety of different parenting styles including permissiveness, overprotectiveness and harsh discipline have been noted to lead to anxiety in children. The two studies on parenting style effects appear to be inconsistent with one focusing on permissiveness and the other on overprotectiveness and harsh disciplinary style. In a study on parents of preschool children (N= 443), the parenting styles and dimensions questionnaire and the child behavior checklist were given [5]. In this study, the parents of anxious children were more permissive. Mothers were more authoritative than fathers, but maternal permissiveness was the most predictive variable for children’s anxiety

In sharp contrast, the prediction of clinically anxious behavior in mid-childhood was predicted by either an over-involved/ protective or a harsh disciplinary parenting style [17]. Parenting style was assessed in Australian parents of preschool children (N=545 children) who were recruited when the children were fouryears- old and they were followed until the children were 7-to-10- years-old. An etiology analysis suggested that parent distress and parenting practices, including over-involved/protective parenting style as well as harsh disciplinary parenting style contributed to anxiety in the children. As many as 57% of the children developed clinically anxious problems. These children, however, were also temperamentally inhibited at the preschool stage, suggesting that the degree to which the children contributed to their own anxiety was not clear. This question could have been addressed by a logistic regression entering parenting style and child inhibition as predictor variables to determine the relative importance of those parenting style and inhibited child variables and the combination of the parent and child variables for the development of anxiety.

Child variables

Other child variables that have been considered risk factors or predictors of anxiety in this recent literature include gender, negative emotionality, irritability, fearfulness and depression. Still other child anxiety predictor variables include less social skill, problematic technology use, attention bias toward negative stimuli, negative expectations, reading and spelling problems and low academic achievement.

Only two research groups have focused on gender being a risk factor for anxiety in children, but their findings were inconsistent. In a study on Canadian kindergarten children, the risk of developing anxiety was greater for males [3]. Between 3.5 and 6.1 higher odds were noted for males scoring below the 10th percentile on social language/ cognition and communication domains. Having a special needs designation was also a risk factor.

In contrast, females were at greater risk in a sample of older children (6-to-16-years-old) in China [1]. Based on the child behavior checklist and the DSMIV, generalized anxiety disorder was the most common at a prevalence rate of 1.3%. Separation anxiety and specific phobias were more prevalent in children versus adolescents. The prevalence in females was greater for panic disorder, agoraphobia and generalized anxiety disorder at a ratio of two to one.

It’s unclear whether these inconsistent findings relate to the differences in age between these two samples. The greater anxiety in males in the younger preschool sample may relate to the generally slower physical and cognitive development of preschool males and the greater anxiety in females at the later childhood and adolescent stage because of their typically greater social anxiety at that stage. These inconsistencies might also reflect cross-cultural differences, variability in the measures of anxiety or in comorbidities. The variability on these factors in several studies has limited the ability to conduct meta-analyses which highlights the methodological limitations of this literature.

Negative emotionality has been another risk factor for anxiety disorders in children [18]. In this study on clinically anxious youth (N=84, mean age =9 years), more severe irritability was noted which led to a greater attention bias towards threat [19]. And these variables were reciprocal with greater anxiety leading to greater attention bias towards threat. As in most studies in this literature, the risk factor and the effect were reciprocal.

In another study focused on attentional bias to threat but in healthy children (N= 95 8- to- 12 year-old children), a few scales were administered including the Childhood Anxiety Sensitivity Index, the Intolerance of uncertainty scale, the perseverative thinking questionnaire and the security scale [20]. Faster detection of anger-oriented stimuli was related to higher Anxiety Sensitivity scores. This relationship was moderated (worsened) by high security Scale scores.

Given the greater attention towards threat, it is not surprising that being fearful was the central symptom of parents and children in another sample [21]. In this study from the Netherlands (N=1452 children and their parents), network analysis was conducted which determined that fearfulness was the central symptom of anxiety in both the parents and children.

A risk factor that could also be considered a comorbid symptom is feeling depressed [22]. This research group reported that anxiety was accompanied not only by feeling depressed, but also by feeling lonely, feeling unloved, worrying, fearing school and talking about suicide. The authors referred to these symptoms as comorbidities.

In a paper entitled “Assessing visual avoidance of faces during real-life social stress in children with social anxiety disorder”, children with and without social anxiety disorder (N=55 9-to-14 years old) were exposed to social stress tasks [23]. The children with social anxiety disorder showed visual avoidance (fewer fixations) of their interaction partners during the second social stress task.

Focused attention has also been a risk factor that was identified in research on play interactions in mother-toddler dyads (N=150) when the toddlers were 12 and 18-months-old [24]. Maternal anxiety led to child anxiety but only for children who showed focused attention during play.

In a study entitled “Social skills and symptoms of anxiety disorders from preschool to adolescence: a prospective cohort”, the Social Skills Rating System was used to assess 4-to-14-yearold children (N=1,043) [25]. Limited social skills led to increased anxiety symptoms at the 8, 10 and 12-month follow-up assessments, but surprisingly, increased anxiety did not lead to decreased social skills.

The importance of social performance is highlighted by a study in which children (N=222 7-to-11-year-old children) watched a film of other children playing kazoo [26]. The filmed children either had a neutral or a negative audience response. The children with anxiety were then filmed playing a kazoo and those who had seen a negative audience response showed a greater anxiety response.

Problematic technology use was a predictor variable for anxiety in children from Spain (N=4025) [27]. The prevalence of anxiety was noted to be greater in older females in this sample. Problematic technology use could have also resulted from elevated anxiety symptoms inasmuch as this was a cross-sectional study in which directionality could not be determined.

Academic problems have also been risk factors for anxiety disorders in children. In a study on literacy difficulties, Greek children in grades two and three (N=121) were noted to have reading and spelling difficulties which led to social anxiety at grade 5 [28]. Academic problems have also been a risk factor for anxiety in two samples of Portuguese children (N= 445 and 448) [6]. In these samples, anxiety increased from childhood to adolescence before decreasing in young adulthood. The risk factors not only included low academic achievement, but also learning disabilities and externalizing symptoms. These problems were likely highly interrelated.

The academic problems may have been related to negative expectations that have been noted in a study entitled “Cognitive variables in social anxiety disorder in children and adolescents: A network analysis” [29]. In this study (N=205 8-18-year-old students), negative expectations were related to the maintenance of social anxiety disorder which was mediated by avoidance.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also contributed to an increased prevalence of anxiety disorder in children from Germany [30]. In data taken from medical records (N= 417,979), anxiety was noted to increase by 9% during COVID. The increase was greater for female versus male children (13% versus 5%). These findings were not surprising as COVID-19 exacerbated many problems in youth including anxiety, depression, eating problems and sleep disturbances [31].

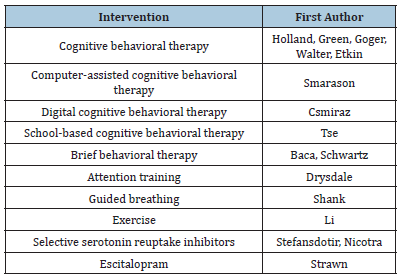

Interventions for anxiety in children

Interventions for anxiety in children have included cognitive behavioral therapy, brief behavioral therapy, attention training, guided breathing, exercise and pharmacotherapy (see Table 4). Although these different interventions have been researched, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been the most frequently reported therapy in this recent literature on anxiety in children (10 papers).

Table 4:Interventions for anxiety in children (and first authors).

In a randomized controlled trial, children were introduced to CBT at age 11 (N= 160) [32]. Cognitive behavioral therapy was notably effective and emotion regulation appeared to mediate the effects of CBT on decreasing anxiety disorder symptoms in a structural equations model. In a meta-analysis on 16 studies on cognitive behavioral therapy, significant improvement occurred not only for anxiety but also for social functioning and relationships [33]. However, there was significant variability on all methodological aspects across the studies.

In research that attempted to increase access to cognitive behavioral therapy, only 3% of children with anxiety disorder had been noted to access CBT [34]. For this study, online support was given to parents and children and 84% agreed to participate. Thirtyeight percent of the children recruited had anxiety symptoms. This high prevalence (38%) would be expected given that 84% of parents agreed to participate in a therapy study, suggesting parental awareness of their children’s anxiety. A significant decrease in anxiety was noted following 8 therapy sessions.

In research that was focused on predictors and moderators of treatment outcomes, children whose parents rated them as having internalizing symptoms (a frequent precursor of anxiety disorder) were randomized to computer-assisted behavior therapy or to a referral for community care [35]. Greater improvement was noted post-treatment for the computer assisted cognitive behavioral therapy group which would be expected given its comparison to a group of children who might have received no treatment.

In a study focused on early indicators of response to treatment of anxiety (N= 95 8-to-16-year-old youth), midpoint measures were taken on anxiety, homework completion, youth and parent engagement [36]. The midpoint symptom measures were significant predictors of the treatment response across 8 sessions.

In a meta-analysis of cognitive behavioral digital interventions for children with anxiety, the CBT interventions were noted to effectively decrease anxiety [37].

In a study on the effectiveness and long -term stability of outpatient cognitive behavior therapy for children with anxiety (N= 220 6-to-18-year-old children), a follow-up was conducted five years later [38]. Medium to large symptom reduction was noted at the end of the study and small to medium reduction was reported for the follow-up measures. Fifty-seven to 70% experienced a decrease in symptoms and 80% reported increased life satisfaction at the follow-up assessment.

In a systematic review of seven studies (5 randomized controlled trials) (N= 2558 6-to-16-year old youth from 138 primary and 20 secondary schools), reduced anxiety was noted following schoolbased cognitive behavioral therapy [39]. Social anxiety disorder was reduced in 86% of the studies. However, the assessments and statistical analyses were highly variable across studies The authors concluded that there was insufficient school funding and staff with relevant background and low level of parental involvement in the school-based cognitive behavioral therapy.

Brief behavioral therapy has also effectively reduced anxiety symptoms. In a study that randomized youth to brief behavioral therapy or community care (N= 52 8-to-16-year-old youth), there was a decrease in avoidance that led to a decrease in anxiety [36].

In another study on brief behavioral therapy, youth were randomly assigned to behavioral therapy or an assisted referral to outpatient care (N= 185 8-to-17-year-old youth) [40]. Following 8-to-12 sessions, there were main and mode rater effects of brief behavioral therapy on change that were largely mediated by the change in anxiety.

Other interventions have included a focus on attention training, guided breathing and exercise. A cognitive training program targeted stimulus-driven attention to alter symptoms of anxiety [41]. In this intervention, 8 sessions of attention training were provided for children with anxiety disorder (N = 18 8-12-years-old). The ratings of anxiety reduction by parents, children and clinicians were correlated with an increase in goal-oriented attention.

In a guided breathing audio-visual intervention, 24 sessions were provided over 8 weeks (N=144 6-to-10-year-old children) [42]. The children were more relaxed after the sessions and by the end of the therapy they had fewer anxiety symptoms.

In the only paper on exercise for reducing anxiety in children, 23 studies were reviewed (N=6830 children) [43]. Exercise reduced anxiety symptoms as well as stress and depression. The most effective protocol was 20-to-45-minute sessions.

Surprisingly, only a few studies on medications were found in this recent literature on interventions for anxiety in children. In one study entitled “Efficacy and safety of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders”, a systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted on 11 studies (N = 2122 17-year- old or younger youth) [44]. The variables that appeared in the 11 studies included remission, social phobia, anxiety inventory for children and adverse events. The SSRIs and the SNRIs versus placebo decreased anxiety, and the risk of serious adverse events was low, but there was an increased risk of experiencing behavioral activation. In another pharmacotherapy intervention for generalized anxiety disorder in children, SSRIs and SSRIs combined with cognitive behavior therapy were the most effective for reducing anxiety [45]. In still another medication study, youth (7-17 year-old youth) were given escitalopram (10-20mg / day) [46]. This was more effective than a placebo in decreasing anxiety symptoms.

To understand the help-seeking behavior of parents of children who experienced anxiety symptoms, a survey was conducted on their knowledge and attitudes as well as their self-efficacy (N=257 parents of 5-12-year- old children) [47]. The authors found that 67% sought help from a general practitioner, 61% from a psychologist and 34% from a pediatrician. The parents reported less stigma and more positive attitudes for seeking help from psychologists.

In the only research that focused on preventing anxiety in this recent literature, a 15-week program was designed to increase prosocial behavior in kindergarten children (N=57) [48]. The children were experiencing anxiety which was positively correlated with emotional symptoms and peer difficulties. Following this intervention, prosocial behaviors increased and they moderated the relationship between high anxiety at the pre-intervention assessment and lower anxiety at the follow-up assessment.

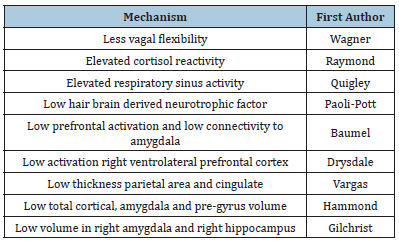

Potential underlying biological mechanisms

Although potential underlying biological mechanisms are rarely discussed in this literature, some research groups have focused on at least one potential underlying mechanism. These include low vagal flexibility, respiratory sinus arrythmia reactivity, elevated cortisol, low BDNF (brain derived neurotrophic factor) and reduced volume in the prefrontal area of the brain, the parietal area and the amygdala (see Table 5).

Table 5:Potential underlying biological mechanisms for anxiety in children (and first authors).

In a paper entitled “Examining the relations between children’s vagal flexibility across social stressor tasks and parent-clinicianrated anxiety”, vagal flexibility was measured [49]. This is considered an index of nonlinear change in parasympathetic nervous system functioning across social stressor tasks. In this study on parents and their 3-5-year-old children (N= 151), less vagal flexibility was related to higher anxiety ratings. Low vagal flexibility occurred in those children with social anxiety disorder.

In longitudinal research on a measure of parasympathetic reactivity, young children’s respiratory sinus arrythmia (RSA) was recorded (N=446 infants and children at 12 months, 3 and 5 years) [50]. RSA reactivity in response to a fearful video led to more internalizing in the children who had been exposed to greater levels of maternal depression or anxiety. The authors concluded that their findings suggested “biological vulnerability to stressful stimuli”.

In a paper entitled “Vulnerability to anxiety differently predicts cortisol reactivity and state anxiety during a laboratory stressor in healthy girls and boys”, healthy children (N=114 8-12-year-old children) experienced a laboratory stressor called the trier social stress test [51]. They were also rated on vulnerability, anxiety, and a composite of the Childhood Anxiety Sensitivity Index, the Intolerance of Uncertainty Questionnaire, and the Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire and cortisol reactivity was assessed. Vulnerability to anxiety was correlated with cortisol reactivity in boys. Irrespective of vulnerability level, girls had a greater response on the state anxiety and stress test.

In a publication entitled “Hair brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) as predictor of developing psychopathological symptoms in childhood”, 117 children were seen at four years (time one) and eight years (time 2) [52]. Time 1 BDNF was negatively associated with time 2 anxiety symptoms and predicted anxiety disorder symptoms at time 2 as well as depressive symptoms, but not ADHD symptoms. The title of this paper was misleading as low hair BDNF was related to anxiety symptoms.

Based on fMRIs, different areas of the brain including the prefrontal and the parietal areas and the amygdala have been implicated in anxiety disorder in children by their changes during treatment. Both psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic treatments have increased the activity in the prefrontal region and enhanced functional connectivity with the amygdala [46]. Another example is taken from a cognitive training program in which there was decreased activity in the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex [41]. In still another fMRI study, scans were taken three times over a two-year period. Lower thickness in both the parietal and cingulate areas was noted in those children experiencing anxiety [53].

In a study entitled “Brain volumes, behavioral inhibition, and anxiety disorders in children”, the sample was drawn from the adolescent brain cognitive development study (N=9,353 9-to -12 year-old children) [2]. Three per cent had an anxiety disorder. Greater total cortical, amygdala and pre-gyrus volumes were associated with lesser odds for anxiety disorders. Those with low behavioral inhibition had greater total white matter in the thalamus and less In the hippocampus. Children with anxiety disorders had less total white matter in the amygdala.

Anxiety disorders have also been reported for children born very preterm [54]. In this research, fMRI data were reported for 124 youth when they were 7-to-13 years old. Less total brain volume as well as less volume in the right amygdala and in the right hippocampus were reported for these youth who had been born very preterm.

It is unclear whether these lesser volumes and abnormal functional connectivity in different areas of the brain are potential underlying biological mechanisms for anxiety in children. Alternatively, they could have derived from anxiety or are possibly related to anxious behavior/feelings the children were experiencing during fMRI sessions. The variability in brain areas affected across studies also suggests age effects or protocol differences in fMRI scans that relate to researcher interests.

Methodological limitations and future research directions

This recent literature on anxiety in children has several methodological limitations that relate to different definitions/ diagnoses of anxiety, sampling, measures, and methods across studies. These limitations are highlighted by several systematic reviews that have been conducted but could not be submitted to meta-analyses because of significant variability of methods and measures across studies that resulted in their failure to meet criteria for meta-analysis

The definitions and diagnostic criteria for anxiety have varied across studies with some researchers sampling children who are simply anxious, have symptoms of anxiety disorder, have social anxiety disorder or who meet the diagnostic criteria for anxiety disorders. And very few researchers have traced the longitudinal course of anxiety disorders in the same children. Most of the samples are children who have been diagnosed with anxiety disorders. Typically, the samples have lacked comparison groups of children without anxiety problems.

The use of different scales in different studies has also made it difficult to compare results across studies. And, the parent-report data are more subjective and less definitive than the more objective physiological measures like cortisol assays and fMRIs that were focused on potential underlying biological mechanisms.

Most of the studies have focused on risk/ predictor variables. These have typically measured one versus multiple variables. Several multiple variable studies have lacked logistic regression analysis or structural equations models to determine the relative significance of the different variables contributing to anxiety. The significant mediating/moderating variables in some of the studies suggest the importance of assessing multiple variables in the same samples. The limited literature on the negative effects of anxiety and the infrequent consideration of comorbidities was unexpected given that research on adults has suggested that anxiety is often accompanied by stress, sleep problems and depression. The absence of research on peer influences on at least social anxiety in this literature was also surprising.

Most of the recent intervention studies have focused on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy which was not surprising since Cognitive Behavioral Therapy is one of the most popular therapies for adult anxiety disorders. Surprisingly, other therapies that have been effective for reducing anxiety in general like massage therapy [16], yoga [55], tai chi [56] and exercise [57] have not appeared in this literature. And, although cognitive behavior therapy has been reputedly effective online and in schools, parental participation was reputedly low. Although parenting styles such as overprotectiveness and permissiveness have been risk factors for anxiety in children, they have not been the focus of intervention studies in this recent literature [58,59].

The potential underlying biological mechanism literature has been primarily fMRI research which is surprising as that is expensive research. The results have been highly variable in terms of the reportedly activated areas of the brain which likely relates to the different age groups and the different severity of anxiety being measured in the children. Some data have suggested that anxiety has been more severe in adolescents than in children.

Despite these methodological limitations, this literature has highlighted the prevalence of anxiety and anxiety disorders in children, with the possibility that the prevalence may have also increased as the overuse of social media has increased, although social media only appeared in one study in this literature. The prevalence of anxiety disorders highlights the need for more intervention research. The data on predictor variables have helped identify children in need of therapy and the intervention data have informed clinicians on potential treatments for children with anxiety disorders. Further research is needed to specify the relative significance of predictor variables for identifying children with anxiety and the specific intervention techniques that are effective in reducing anxiety in children.

References

- Wang F, Yang H, Li F, Zheng Y, Xu H, Wang R, Li Y, Cui Y. et al. (2024) Prevalence and comorbidity of anxiety disorder in school-attending children and adolescents aged 6-16 years in China. BMJ Paediatr Open 8(1): e001967.

- Hammoud RA, Ammar LA, McCall SJ, Shamseddeen W, Elbejjani M (2024) Brain volumes, behavioral inhibition, and anxiety disorders in children: Results from the adolescent brain cognitive development study. BMC Psychiatry 24(1): 257.

- Janus M, Ryan J, Pottruff M, Reid WC, Brownell M, et al. (2023) Population-based teacher-rated assessment of anxiety among Canadian kindergarten children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 54(5): 1309-1320.

- Mutluer T, Gorker I, Akdemir D, Ozdemir DF, Ozel OO, et al. (2022) Prevalence, comorbidities and mediators of childhood anxiety disorders in urban Turkey: A national representative epidemiological study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 58(6): 919-929.

- Kadoglou M, Tziaka E, Samakouri M, Serdari A (2024) Preschoolers and anxiety: The effect of parental characteristics. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs 37(1): e12445.

- LoParo D, Fonseca AC, Matos APM, Craighead WE (2024) Anxiety and depression from childhood to young adulthood: Trajectories and risk factors. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 55(1): 127-136.

- Cervin M (2023) Sensory processing difficulties in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive and anxiety disorders. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol 51(2): 223-232.

- Howe DH, Hobson C, Waters C, Van Goozen SHM (2023) Emotional and socio-cognitive processing in young children with symptoms of anxiety. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 32(10): 2077-2088.

- Halldorsson B, Waite P, Harvey K, Pearcey S, Creswell C (2023) In the moment social experiences and perceptions of children with social anxiety disorder: A qualitative study. Br J Clin Psychol 62(1): 53-69.

- Aucoin P, Gardam O, St John E, Kokenberg GL, Corbeil S, et al. (2023) COVID-19-related anxiety and trauma symptoms predict decreases in body image satisfaction in children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 54(6): 1666-1677.

- Tan WJ, Ng MSL, Poon SH, Lee TS (2023) Treatment implications of sleep-related problems in pediatric anxiety disorders: A narrative review of the literature. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 54(3): 659-664.

- Buckley V, Young AH, Smith P (2023) Child and adolescent anxiety as a risk factor for bipolar disorder: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Bipolar Disord 25(4): 278-288.

- Galbally M, Watson SJ, Van IJzendoorn MH, Tharner A, Luijk M, et al. (2023) Prenatal predictors of childhood anxiety disorders: An exploratory study of the role of attachment organization. Dev Psychopathol 35(3): 1296-1307.

- Kirkpatrick A, Serbin LA, Stack DM (2024) Do you see what I see? Exploring maternal and child perceptions of children's anxiety longitudinally. Dev Psychol 60(1): 187-198.

- Tu EN, Manley H, Saunders KEA, Creswell C (2024) Systematic review and meta-analysis: risks of anxiety disorders in offspring of parents with mood disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 63(4): 407-421.

- Field T (2024) Massage therapy research: A narrative review. Current Research in Psychology and Behavioral Science 5(1): 1-7.

- Bayer JK, Prendergast LA, Brown A, Bretherton L, Hiscock H, et al. (2021) Prediction of clinical anxious and depressive problems in mid childhood amongst temperamentally inhibited preschool children: A population study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 32(2): 267-281.

- Raines EM, Viana AG, Trent ES, Conroy HE, Silva K, et al. (2023) Effortful control moderates the relation between negative emotionality and child anxiety and depressive symptom severity in children with anxiety disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 54(1): 17-25.

- Elvin OM, Waters AM, Modecki KL (2023) Does irritability predict attention biases toward threat among clinically anxious youth? Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 32(8): 1435-1442.

- Raymond C, Cernik R, Beaudin M, Arcand M, Pichette F, et al. (2024) Maternal attachment security modulates the relationship between vulnerability to anxiety and attentional bias to threat in healthy children. Sci Rep 14(1): 6025.

- Baartmans JMD, Van Steensel BFJA, Kossakowski JJ, Klein AM, Bögels SM (2024) Intergenerational relations in childhood anxiety: A network approach. Scand J Psychol 65(2): 346-358.

- Sánchez HMO, Carrasco MA, Holgado TFP (2023) Anxiety and depression symptoms in Spanish children and adolescents: An exploration of comorbidity from the network perspective. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 54(3): 736-749.

- Lidle LR, Schmitz J (2024) Assessing visual avoidance of faces during real-life social stress in children with social anxiety disorder: A mobile eye-tracking study. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 55(1): 24-35.

- Egotubov A, Gordon HA, Sheiner E, Gueron SN (2023) Maternal anxiety and toddler depressive/anxiety behaviors: The direct and moderating role of children's focused attention. Infant Behav Dev 70: 101800.

- Habibi AM, Steinsbekk S, Wichstrøm L (2023) Social skills and symptoms of anxiety disorders from preschool to adolescence: a prospective cohort study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 64(7): 1045-1055.

- Mills C, Tenenbaum HR, Askew C (2023) Effects of peer vicarious experience and low effortful control on children's anxiety in social performance situations. Dev Psychol 59(5): 813-828.

- Luengo GR, Noriega MMC, Espín LEJ, García SMM, Rodríguez RIC, et al. (2022) The role of life satisfaction in the association between problematic technology use and anxiety in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Ment Health Nurs 32(1): 212-222.

- Kargiotidis A, Manolitsis G (2024) Are children with early literacy difficulties at risk for anxiety disorders in late childhood? Ann Dyslexia 74(1): 82-96.

- Vogel F, Reichert J, Hartmann D, Schwenck C (2023) Cognitive variables in social anxiety disorder in children and adolescents: A network analysis. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 54(3): 625-638.

- Kostev K, Weber K, Riedel HS, Von Vultée C, Bohlken J (2023) Increase in depression and anxiety disorder diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic in children and adolescents followed in pediatric practices in Germany. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 32(5): 873-879.

- Field T (2021) COVID-19 and pediatric problems: A narrative review. Medical Research Archives 9(5): 1-12.

- Helland SS, Baardstu S, Kjøbli J, Aalberg M, Neumer SP (2023) Exploring the mechanisms in cognitive behavioural therapy for anxious children: Does change in emotion regulation explain treatment effect? Prev Sci 24(2): 214-225.

- Etkin RG, Juel EK, Lebowitz ER, Silverman WK (2023) Does cognitive-behavioral therapy for youth anxiety disorders improve social functioning and peer relationships? Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 26(4): 1052-1076.

- Green I, Reardon T, Button R, Williamson V, Halliday G, et al. (2022) Increasing access to evidence-based treatment for child anxiety problems: online parent-led CBT for children identified via schools. Child Adolesc Ment Health 28(1): 42-51.

- Smárason O, Guzick AG, Goodman WK, Salloum A, Storch EA (2023) Predictors and moderators of treatment outcomes for anxious children randomized to computer-assisted cognitive behavioral therapy or standard community care. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 33(8): 316-324.

- Baca SA, Goger P, Glaser D, Rozenman M, Gonzalez A, et al. (2023) Reduction in avoidance mediates effects of brief behavioral therapy for pediatric anxiety and depression. Behav Res Ther 164: 104290.

- Csirmaz L, Nagy T, Vikor F, Kasos K (2024) Cognitive behavioral digital interventions are effective in reducing anxiety in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Prev (2022) 45(2): 237-267.

- Walter D, Behrendt U, Matthias EK, Hellmich M, Dachs L, et al. (2023) Effectiveness and long-term stability of outpatient cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for children and adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders under routine care conditions. Behav Cogn Psychother 51(4): 320-334.

- Tse ZWM, Emad S, Hasan MK, Papathanasiou IV, Rehman IU, et al. (2023) School-based cognitive-behavioural therapy for children and adolescents with social anxiety disorder and social anxiety symptoms: A systematic review. PLoS One 18(3): e0283329.

- Schwartz KTG, Kado WM, Dickerson JF, Rozenman M, Brent DA, et al. (2023) Brief behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in pediatric primary care: Breadth of intervention impact. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 62(2): 230-243.

- Drysdale AT, Myers MJ, Harper JC, Guard M, Manhart M, et al. (2023) A novel cognitive training program targets stimulus-driven attention to alter symptoms, behavior, and neural circuitry in pediatric anxiety disorders: Pilot clinical trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 33(8): 306-315.

- Shank LM, Grace V, Delgado J, Batchelor P, De Raadt St JA, et al. (2023) The impact of a guided paced breathing audiovisual intervention on anxiety symptoms in Palestinian children: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Child Adolesc Ment Health 28(4): 473-480.

- Li J, Jiang X, Huang Z, Shao T (2023) Exercise intervention and improvement of negative emotions in children: A meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr 23(1): 411.

- Stefánsdóttir ÍH, Ivarsson T, Skarphedinsson G (2023) Efficacy and safety of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nord J Psychiatry 77(2): 137-146.

- Nicotra CM, Strawn JR (2023) Advances in pharmacotherapy for pediatric anxiety disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 32(3): 573-587.

- Baumel WT, Strawn JR (2023) Neurobiology of treatment in pediatric anxiety disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 32(3): 589-600.

- Ma SON, McCallum SM, Pasalich D, Batterham PJ, Calear AL (2023) Understanding parental knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy in professional help-seeking for child anxiety. J Affect Disord 337: 112-119.

- Lewis KM, Barrett P, Freitag G, Ollendick TH (2023) An ounce of prevention: Building resilience and targeting anxiety in young children. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 28(2): 795-809.

- Wagner NJ, Shakiba N, Bui HNT, Sem K, Novick DR, et al. (2023) Examining the relations between children's vagal flexibility across social stressor tasks and parent- and clinician-rated anxiety using baseline data from an early intervention for inhibited preschoolers. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol 51(8): 1213-1224.

- Quigley KM, Petty CR, Sidamon EAE, Modico M, Nelson CA, et al. (2023) Risk for internalizing symptom development in young children: Roles of child parasympathetic reactivity and maternal depression and anxiety exposure in early life. Psychophysiology 60(10): e14326.

- Raymond C, Pichette F, Beaudin M, Cernik R, Marin MF (2023) Vulnerability to anxiety differently predicts cortisol reactivity and state anxiety during a laboratory stressor in healthy girls and boys. J Affect Disord 331: 425-433.

- Pauli PU, Cosan AS, Schloß S, Skoluda N, Nater UM, et al. (2023) Hair brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) as predictor of developing psychopathological symptoms in childhood. J Affect Disord 320: 428-435.

- Vargas TG, Mittal VA (2023) Brain morphometry points to emerging patterns of psychosis, depression, and anxiety vulnerability over a 2-year period in childhood. Psychol Med 53(8): 3322-3334.

- Gilchrist CP, Thompson DK, Alexander B, Kelly CE, Treyvaud K, et al. (2023) Growth of prefrontal and limbic brain regions and anxiety disorders in children born very preterm. Psychol Med 53(3): 759-770.

- Field T (2023) Yoga therapy research: A narrative review. Current Research in Complementary and Alternative Medicine 7: 223.

- Field T (2023) Tai chi therapy research: A narrative review. Current Research in Complementary and Alternative Medicine 7: 199.

- Field T (2023) Exercise therapy reduces pain and stress: A narrative review. Current Research in Complementary and Alternative Medicine 7: 220.

- Goger P, Rozenman M, Gonzalez A, Brent DA, Porta G, et al. (2023) Early indicators of response to transdiagnostic treatment of pediatric anxiety and depression. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 64(12): 1689-1698.

- Strawn JR, Moldauer L, Hahn RD, Wise A, Bertzos K, et al. (2023) A multicenter double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of escitalopram in children and adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 33(3): 91-100.

© 2024 Tiffany Field. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)