- Submissions

Full Text

Research in Pediatrics & Neonatology

Mechanism of Temporary Trapped Penis in Circumcision: Some Theories

Mustafa Akman*

Department of Pediatric Surgery, Medipol University, Turkey

*Corresponding author: Mustafa Akman, Medipol University, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Pediatric Surgery, İstanbul, Turkey

Submission: November 19, 2021; Published: January 12, 2022

ISSN: 2577-9200 Volume6 Issue2

Abstract

Background: There are complications and bleeding differences among obese and buried penis cases.

Bleeding symptoms in these cases may not indicate the amount of bleeding. Continuation of bleeding

without symptoms may bring along other problems such as trapped penis.

Objective: Aim of the study is to draw attention to hematoma and associated trapped penis cases, to

explain the mechanism of trapped penis formation through established theories based on the fluid mechanics,

to demonstrate that minor hemorrhages, which occur in patients with the buried penis, may be

incompatible with the amount of bleeding.

Materials & methods: Patients with penile/perineal hematoma that developed after routine ritual circumcision,

which was performed under local anesthesia in healthy individuals, were included in the study

group, and their clinical characteristics were examined. Clinical and hematological conditions were noted

down. It was planned to establish a bleeding model based on the topographic structure of the buried

penis and under principles of fluid mechanics.

Results: Seven patients who developed penile/perineal hematoma and associated trapped penis complications

after 901 circumcision procedures were included in the study. It was determined that the bleeding

stopped in an average of 3.42 hours, and the trapped penis condition started in an average of 3.41

hours. It was found that the trapped penis and skin discoloration disappeared completely in an average of

5.00 and 8.14 days respectively. The model was established according to the principles of fluid mechanics

by evaluating the bleeding, which occurred due to the change of position upon the telescopic movement

during the circumcision procedure of the buried penis cases in the fat pad.

Discussion: In the literature, trapped penis cases have been discussed, but edema, regional hematoma,

and temporary trapped penis formation have not been addressed. The main limitation of our study is

that tissue viscosity and coagulation properties are not addressed under the principles of fluid mechanics,

there is no other study by which we can evaluate the pathology, the number of cases in our study is

limited.

Conclusion: Positioning of the buried penis could reveal different bleeding characteristics, and trapped

penis may develop. Telescopic movement of the penis could be considered as a reason for the hematoma

to occur in the subcutaneous and perineal areas. In patients with the hidden penis, the amount of bleeding

may not be noticed in the first hours since the area where the bleeding pools are hidden.

Keywords:Circumcision; Trapped penis; Mechanism; Hematoma; Bleeding

Highlights

A. Circumcision complications can be affected by anatomical differences.

B. The amount of macroscopic bleeding that occurs in individuals with a buried penis may

not reflect the actual amount of bleeding.

C. Minor bleeding in different areas may lead to major symptoms.

D. Elaborating the anatomical differences before making a circumcision decision would

contribute to the reduction of complications.

Introduction

Circumcision, which is the oldest and most common surgical procedure across the world, continues to be performed via modern and conventional techniques. Currently, there are aspects of circumcision that still need to be investigated. Complications of the procedure have been reported as less than 1% in some studies, whereas in other studies, it has been reported to be more than 25%. Bleeding is one of the most popular studies on circumcision. Numerous studies have discussed how to reduce circumcision bleeding and whether differences are depending on the performed techniques. In the literature review that we conducted before starting our study, it was found that there was a lack of information regarding the association between anatomical changes and bleeding as well as about the topographic effect of bleeding [1-5].

Many studies have examined and assessed the treatment of the trapped penis that occurred after circumcision. As Bolnick DA et al. [2] points out, there is uncertainty in the contribution of anatomical differences to bleeding. The objective of our study is to evaluate post-circumcision bleeding, the topographic effect of penile/perineal hematoma and trapped penis cases in patients with the hidden penis, to reveal the mechanism of trapped penis formation by developing a theoretical model, and draw attention to these aspects that have not been investigated in circumcision research hitherto [2,6-8].

Materials and Methods

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

A. Patients who had circumcision bleeding and developed penile/

perineal hematoma were included in the study.

B. Patients who had circumcision bleeding but did not develop

penile/perineal hematoma were excluded from the study.

C. One patient whose parents gave written and verbal consent to

participate in the illustrated examination was included in the

illustrated study.

D. The patients whose parents did not give written and verbal

consent to participate in the pictorial examination were

excluded from the illustrated study. These patients were

included in the general study with parental consent.

E. Patients who had been circumcised under local anesthesia

were included in the study.

F. Patients who had been circumcised under general anesthesia

were not included in the study.

Of 901 patients who had been circumcised under local anesthesia between March 2019 and December 2020, those who developed penile/perineal hematoma after the procedure were included in the study. Patients who underwent general anesthesia were not evaluated in the study due to differences in methods. 901 circumcision procedures were started with bleeding/ coagulation assessment and EMLA application to the root of the penis. Local anesthesia was achieved through injecting adrenalinefree Lidocaine at 3 sites. Circumcision was performed by a single surgeon by dorsal slit technique. The bleeding control was achieved with bipolar cautery, and the skin integrity was achieved using absorbable multifilament sutures. Simple bandaging was applied to patients without a hidden penis.

The parents of the patients with hidden penises were taught penile massage to be applied regularly. Patients without bleeding or pain were discharged with the prescriptions of oral paracetamol and topical antibiotic cream. A follow-up examination was performed at least once in all patients. Trapped penis developments were detected in these follow-up examinations. Oral medication, perineal appearance documentation, and Kayaba classification were not applied before the procedure [9].

Patients who were found to have developed penile/perineal hematoma during follow-up examination were included in the study group. Patients who had bleeding, yet no penile/perineal interaction were excluded. In the follow-up examination of the patients, it was confirmed that there was no history of prolonged bleeding. Bleeding/Coagulation tests were repeated. Complete blood count was performed, but factor tests were not performed. General body examination, bleeding details, onset end times of trapped penis, and details of the intervention, if performed, were noted down. Simple hematoma evacuation was applied to patients if it is possible. Upon predicting that the patients would not develop major complications, the outpatient follow-up of the patient was continued by informing the parents about nutritional reluctance, discomfort, urinary retention, and fever. Follow-up of the patients whose skin discoloration completely disappeared was discontinued.

Statistical analysis

Since the number of cases did not reach the minimum number required for significant statistical analysis, we made do with analyzing the distribution normality [10].

Results

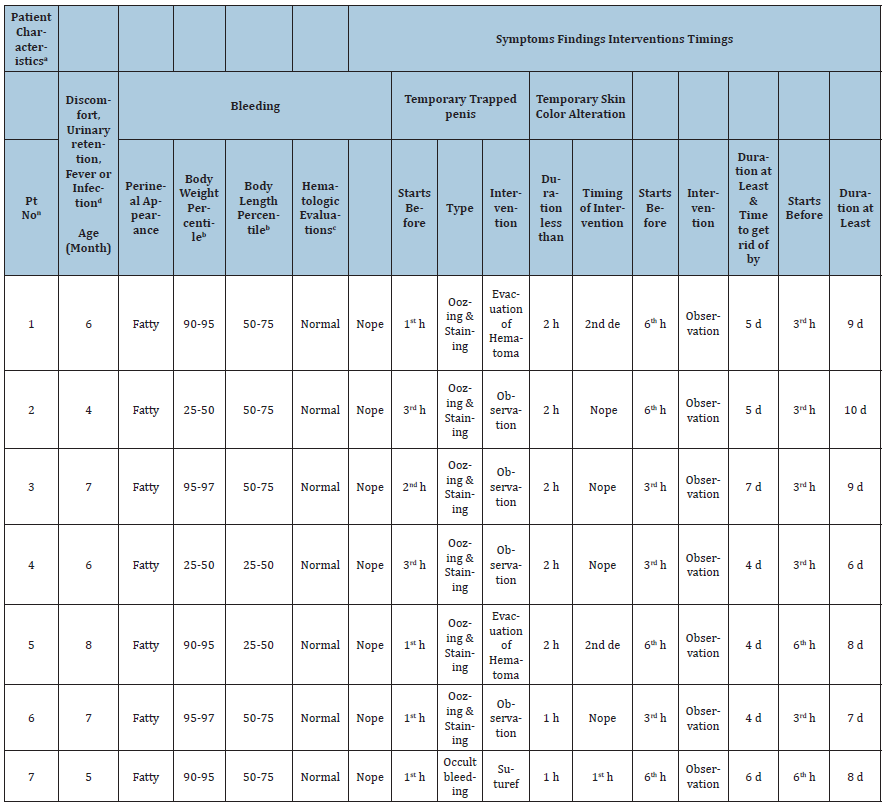

Perineal fatty appearance and hidden penis were observed in seven patients with penile/perineal hematoma during the preprocedure examination. In patients aged 4-8 months (mean=6.14) obtained percentiles values were as follows; height 25th-50th (n=2) and 50th -75th (n=5); Weight 25th -50th (n=2), 90th -95th (n=3) and 95th -97th (n=2) (Table I).

Bleeding of patient 7, who required early intervention after circumcision, occurred within the first hour following the procedure. It was found that the stain-like bleeding of those, who were followed up through observation, developed in 1-3 hours (Mean=1.71), and 2 patients who had hematoma evacuation had bleeding in the first hour after the procedure. It was determined that the bleeding, which was visible in inspection, continued for 1-2 hours (Mean=1.71). In the follow-up examination, no patient was detected with the symptom of active bleeding. It was found that the bleeding completely disappeared between 2-5 hours after the procedure (mean=3.42).

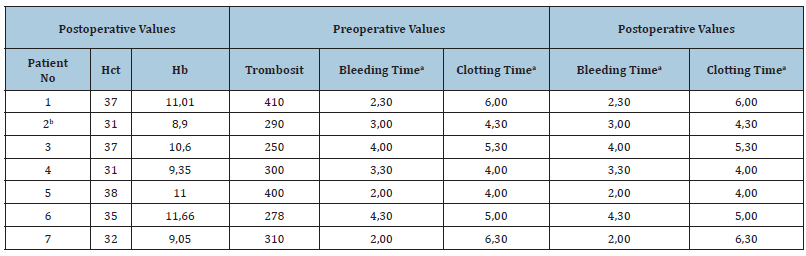

Penis massage has been the most valuable factor in helping us to find out the details of trapped penis cases. It was determined that the trapped penis started in the 3-6th hour (Mean=4.71) and recovered in 4-7 days (Mean=5.00). It was observed that the skin discoloration started within 3-6 hours (Mean=3.86) and ended in 6-10 days (Mean=8.14). Erythema and leukocytosis suggestive of lack of appetite, fever, inability to urinate, discomfort, and signs of infection were not detected in the patients. In all patients, the end of the trapped penis condition occurred before the discoloration. It was observed that the discoloration improved 2-5 days after the correction of the trapped penis (mean=2.85). Macroscopic abnormalities such as skin bridge, adhesions, and permanent trapped penis were not observed In the early period (Table 1). Based on the hematological tests that were performed after the hematoma, it was detected that the bleeding coagulation assessments performed before and after the procedure were within normal limits (Table 2).

Table 1: (Patient Characteristics).

aConsist of pre-and post-hematoma evaluations detailed in Table 2; bAccording to: doi.10.3109&03014460.2011.605800; cBleeding & coagulation tests, hemogram; dEarly or Late; eBetween postoperative 48th & 60th hours; fDorsal suturing; n7 patients out of 901. Abbreviation: h: Hour(s), d: Days.

Table 2:Hematologic Evaluations. aminute, second.

Discussion

The trapped penis is associated with a buried penis but is not the same phenomenon. The trapped penis is an acquired form of the hidden (concealed) penis. It has been stated that the trapped penis often occurs after neonatal circumcision or trauma when scar tissue traps the penis under the prepubic area or scrotal skin. The shaft of the penis is fully or partially squeezed. Byars & Trier [11] were the first to identify this phenomenon that required surgical intervention. In our study, a case of trapped penis not related to scar tissue is discussed [12,13].

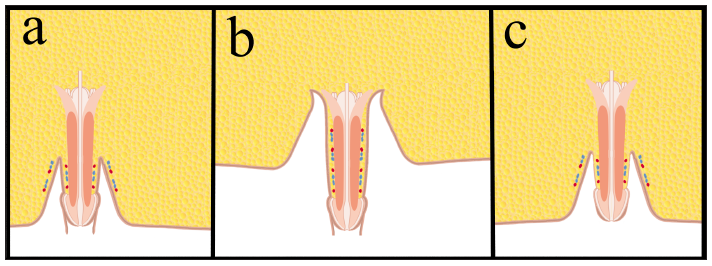

The hidden penis can be discussed under various headings. It can be classified as congenital or acquired, based on the anatomical topographic appearance of it. The natural fat distribution changes of the person may have an impact on it and can improve with growth. According to the Maizels’ classification, a hidden penis is defined as a normal-sized phallus buried in prepubic tissue, located in scrotal tissue, or trapped in scrotal tissue after penile surgery. Considering the nature of our study, it may be more appropriate to examine it in two separate categories as the temporary or permanent hidden penis (Figure 1) [14-18].

Figure 1: Telescopic movement of penis.

In obese patients, the penis is often buried, and the soaring rate of obesity has increased the incidence of the hidden penis as well. It has been revealed that one of the reasons why institutions such as AAP/EUA/NHL do not recommend circumcision except for medical necessity is due to the high rate of circumcision complications in obesity. Obesity is not considered a definitive contraindication for circumcision. However, it has been put forward that patients with normal percentile values should be treated more meticulously and postponed until the fatty tissue in the area is recovered. The AAP recommends elaborating the penis examination by manually retracting the suprapubic fat pad in the pre-circumcision examination. It has been underscored that serious problems may be encountered otherwise. Shapiro [14] suggested that obesity contributes to bleeding [2,14,19-22].

Wiswell TE et al. [23], who performed circumcision in a series of 136,086 cases, which is one of the large series, found the bleeding and infection rate to be 0.2%. Bhat NA et al. [24] assessments, in which large case series have been examined, are another of these studies. In these two studies, anti-bleeding surgical techniques were examined, but no research was conducted on the topographic effect of bleeding [23-25].

Talini C et al. [26] addressed the issue of the bleeding mechanism, pointed out the insufficient bonding of the ring in the use of Plastibell© device, and made do with expressing it as predisposing foreskin retraction and dislodgement of the ring. Netto JMB et al. [27] demonstrated the presence of local edema and hematoma caused by the application of a local anesthetic substance to the penis after circumcision and suggested that it was overcome through simple measures without experiencing any problems, similar to our study; however, they did not give any further detail. In the study of Marwat AA et al. [28] in which 780 circumcisions performed with a Plastibell© device were evaluated, the penile hematoma was found with an incidence of 1.51%. Trapped penis development and hemorrhage tomography were not addressed in either study. Mense L et al. [29] assessed one circumcision case with oozing-like bleeding. The case in the study involves a persistent hemorrhage. In the study, it was stated that major bleeding after circumcision is rare, hematological assessments are not required before the procedure, and detailed examinations may be required only for prolonged bleeding [26-29].

In the seven hematoma cases we detected in our circumcision series, it was observed that bleeding, which was not considered significant initially caused penile/perineal hematoma, leading to the trapped penis. Through the model we established, we tried to reveal the topographic effect of bleeding. With our theory, which needs to be detailed and supported by further studies, the hypothesis has been reached that the edema of the penile body and hematoma developing in the area during circumcisions, which were performed with local anesthesia, could be eliminated.

Figure 2a and Figure 2b, show the 5th day when the pathology of the trapped penis condition, which occurred in the case numbered with 2 in Table 1, recovered. Picture IIc belongs to the 7th day. The discoloration has not yet regressed fully. It was observed that the ½ proximal part of the patient’s penis shaft was affected, and it was determined through manually created erection that there was no hematoma in the distal penile areas (Figure 2a-c). It was considered that the penile/perineal hematoma area in the patient could match up with the shifted skin area depicted in Figure 3a and Figure 3b.

Figure 2: Case number 2 follow up.

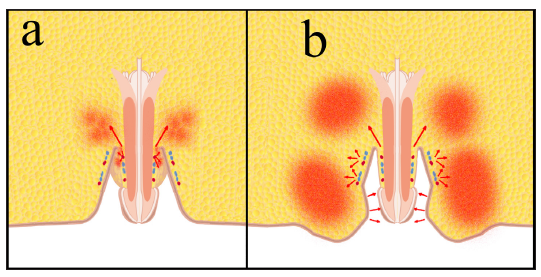

Figure 3: Mechanism of Hematoma and trapped penis.

Theories

Theory I

It was thought that in obese patients or patients with regional adipocytes, the penis was inverted due to the telescopic movement of the penile skin following the release of the penis (Figure 1c) after the demonstration of the anatomy of the penis as suggested by AAP (Figure 1) and after the circumcision performed in the same position (Figure 1b). Based on Bernoulli’s principle in fluid mechanics and this current topographic situation, it was considered that the area where hemorrhage can progress most easily may be the neighboring area, perineal fat tissue, and hematoma may occur in this area (Figure 3).

Theory II

Edema of the penile body could change the direction of the hemorrhage arising from the dorsal artery and vein extending in the superficial fascia by squeezing the penile body like a sleeve due to its topographic proximity with the surrounding tissues (Figure 1a).

In this model, there must be vein ends that have shifted into the adipose tissue together with the skin of the penis. Based on Bernoulli’s principle, Newton’s law of viscosity, and Newton’s Second Law in fluid mechanics, prevention of the flow provided by the difference between the peripheral pressure of 8-10 mmHg in normal physiology and 0-6mmHg of the right atrium with edema may contribute to the growth of perineal hematoma by occurring much earlier than the arterial system operating with positive pressure. Penile lymphatic drainage, which drains into the inguinal region and has pressure values of 0.3-3mmHg in normal physiology, might have an impact on penile edema by undergoing current changes due to edema and hematoma in the area [30].

Theory III

According to Bernoulli’s principle and Newton’s Second Law in fluid mechanics, the hematoma arising from the proximal of the penis and formed in the perineal area, its topographic neighborhood and mechanical effect, and the pressure effect it would create from the glans level could impact the direction of hemorrhage originating from the dorsal artery and vein extending in the superficial fascia (Figure 3b). We consider this premise to be the weakest theory [30].

Fluid mechanics principles [31-34]:

A. Newton’s Second Law As a fluid particle moves from one

location to another, it usually experiences an acceleration or

deceleration. According to Newton’s second law of motion, the

net force acting on the fluid particle under consideration must

equal its mass times its acceleration, F=ma.

B. Bernoulli’s principle: Fluids flow from areas of high pressure

to areas of low pressure.

C. When the external force is applied, they constantly change

their location until the molecular external force is removed,

and ultimately, they cannot return to their former form.

D. Newton’s law of viscosity: Viscosity is the physical property

that characterizes the flow resistance of simple fluids.

Newton’s law of viscosity defines the relationship between the

shear stress and shear rate of a fluid subjected to mechanical

stress. The ratio of shear stress to shear rate is a constant, for a

given temperature and pressure, and is defined as the viscosity

or coefficient of viscosity. Newton’s law of viscosity can be

evaluated as to contain bleeding in the tissue.

Conclusion

Circumcision is elective. Hence, it is necessary to identify unsuitable candidates, be careful about the timing of circumcision, and know the details related to complications. In the first examination, the appearance of the penis is preferred to be normal. If the expected penis appearance is not available at the first examination, the examination should be elaborated. No matter what underlies beneath the reason for the buried (hidden) penis, whether it is perineal local fat pads or general body fat distribution, circumcision scheduled in such cases requires being meticulous. Before beginning the circumcision procedure, the penis should be fully exposed by pushing the perineal adipose tissue and the condition of the penis should be evaluated as suggested by the AAP.

Circumcision bleeding in patients with the hidden penis may manifest itself with different symptoms. When the vascular line in the circumcision incision line, which is pulled into the perineal fat pad with a telescopic movement, bleeds, it may lead to deviations in the natural flow of fluids in accordance with the laws of fluid mechanics, causing them to accumulate in the perineal fat tissue. Penile/perineal hematoma, which may occur in this way, could be the cause of the trapped penis. Similarly, edema in the penis, which was buried in the perineum after circumcision, may impact venous and lymphatic return. This can both increase edema and change the pattern of bleeding. We tried to explain this situation in our study, which needs to be confirmed by further studies. We consider it more appropriate to term these cases “temporary Trapped penis” and cases that occur due to fibrosis as “permanent trapped penis”.

All of the temporary trapped penis cases that developed in our case series, which included a small number of patients, differentiated from permanent trapped penis cases, which require surgical intervention, in terms of their recovery without any permanent complications. We are of the opinion that dorsal or ventral wound margin hemorrhages far from the glans contributed to the temporary trapped penis case, rather than the frenulum artery bleeding adjacent to the Glans. We interpret the macroscopic development of the trapped penis after the end of the bleeding as ongoing bleeding that progresses into the tissue and pools in this area.

Future Workouts

A. A prospective study needs to be conducted to assess

circumcisions performed in patients with perineal fatty

appearance or obesity.

B. Patients with developed hematoma should be followed up with

imaging studies, and anatomical details should be evaluated.

C. Hematoma regression processes should be confirmed.

D. Patients should be involved in long-termed follow-ups, and the

impacts of percentile changes on penile aesthetics should be

assessed.

E. Further studies should be carried out to assess the effects

of early hematoma evacuation on penile aesthetics and

temporary or permanent trapped penis.

F. The hematoma/ischemia relationship should be revealed

by examining penile arterial and venous systems, and its

association with hematoma should be demonstrated.

Limitations

A. The number of patients who developed hematoma did not

reach a number through which a statistically acceptable result

can be obtained.

B. No comparison could be made with similar studies of other

centers that revealed an association between bleeding and

adiposity.

C. The difference between general anesthesia and local anesthesia

was not assessed.

D. The effects of the patients’ percentile changes were not

evaluated with their late follow-up.

E. Circumcisions performed in patients with perineal fatty

appearance or obesity were not evaluated prospectively, and

patients with complications were evaluated.

Coagulation capacity and tissue viscosity variables were not

taken into consideration in Newton and Bernoulli’s principles.

References

- Chaim BJ, Livne PM, Binyamini J, Hardak B, Ben-Meir D, et al. (2005) Complications of circumcision in Israel: A one year multicenter survey. Isr Med Assoc J 7(6): 368-370.

- Bolnick DA, Koyle M, Yosha A (2012) Surgical guide to circumcision. Anatomic contraindications to circumcision. Springer Books, New York , USA, pp: 33-43.

- Horowitz M, Gershbein AB (2001) Gomco circumcision: When is it safe? J Pediatr Surg 36(7): 1047-1049.

- Mousavi SA, Salehifar E (2008) Circumcision complications associated with the Plastibell device and conventional dissection surgery: A trial of 586 infants of ages up to 12 months. Adv Urol 2008: 606123.

- (2010) Neonatal and child male circumcision: A global review. WHO Library, Geneva.

- King ICC, Tahir A, Ramanathan C, Siddiqui H (2013) Buried penis: Evaluation of outcomes in children and adults, modification of a unified treatment algorithm, and review of the literature. ISRN Urol 2013: 109349.

- Mirshemirani A, Tabari AK, Rozroukh M, Ghoroubi J, Mohajerzadeh L, et al. (2017) Management and outcomes of hidden penis in children. Iranian Journal of Pediatric Surgery 3(2): 94-99.

- Valioulis IA, Kallergis IC, Ioannidou DC (2015) Correction of concealed penis with preservation of the prepuce. J Pediatr Urol 11(5): 259.

- Kayaba H, Tamura H, Kitajima S, Fujiwara Y, Kato T, et al. (1996) Analysis of shape and retractability of the prepuce in 603 Japanese boys. J Urol 156(5): 1813-1815.

- Sakpal TV (2010) Sample size estimation in clinical trial. Perspect Clin Res 1(2): 67-69.

- Byars LT, Trier WC (1958) Some complications of circumcision and their surgical repair. AMA Arch Surg 76: 477-482.

- Trier WC, Drach GW (1973) Concealed penis another complication of circumcision. Am J Dis Child 125(2): 276-277.

- Elbatarny AM (2014) Surgical treatment of post circumcision trapped penis. Ann Pediatr Surg 10(4): 119-124.

- Shapiro SR (1987) Surgical treatment of the buried penis. J Urol 30(6): 554-559.

- Maizels M, Meade P, Rosoklija I, Mitchell M, Liu D (2019) Outcome of circumcision for newborns with penoscrotal web: oblique skin incision followed by penis shaft skin physical therapy shows success. J Pediatr Urol 15(4): 404.e1-404.e8.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision (2012) Circumcision policy statement. Pediatrics 130(3): 585-586.

- Tekgül S, Dogan HS, Hoebeke P, Kocvara R, Nijman JM, et al. (2016) EAU guidelines on paediatric urology. European Society for Paediatric Urology, pp: 1-136.

- Mirastschijski U (2018) Classification and treatment of the adult buried penis. Ann Plast Surg 80(6): 653-659.

- Storm DW, Baxter C, Koff SA, Alpert S (2011) The relationship between obesity and complications after neonatal circumcision. J Urol 186(4 Suppl): 1638-1641.

- Eroğlu E, Bastian OW, Ozkan HC, Yorukalp OE, Goksel AK (2009) Buried penis after newborn circumcision. J Urol 181(4): 1841-1843.

- Mayer E, Caruso DJ, Ankem M, Fisher MC, Cummings KB, et al. (2003) Anatomic variants associated with newborn circumcision complications. Can J Urol 10(5): 2013-2016.

- Alter GJ, Horton CE, Horton CE (1994) Buried penis as a contraindication for circumcision. J Am Coll Surg 178(5): 487-490.

- Wiswell TE, Geschke DW (1989) Risks from circumcision during the first month of life compared with those for uncircumcised boys. Pediatrics 83(6):1011-1015.

- Bhat NA, Raashid H, Rashid KA (2014) Complications of circumcision. Saudi Journal of Medicine & Medical Sciences 2(2): 86-89.

- Palit V, Menebhi DK, Taylor I, Young M, Elmasry Y, et al. (2007) A unique service in UK delivering Plastibell circumcision: Review of 9-year results. Pediatr Surg Int 23(1): 45-48.

- Talini C, Antunes LA, Carvalho BCN, Schultz KL, Del Valle MHCP, et al. (2018) Circumcision: Postoperative complications that required reoperation. Einstein (São Paulo) 16(3): eAO4241.

- Netto JMB, Araújo JGd, Noronha MFdA, Passos BR, Lopes HE, et al. (2013) A prospective evaluation of plastibell® circumcision in older children. Int Braz J Urol 39(4): 558-564.

- Marwat AA, Hashmi ZA, Waheed D (2010) Circumcision with plastibell device: An experience with 780 children. Gomal J Med Sci 8: 30-33.

- Mense L, Ferretti E, Ramphal R, Daboval T (2018) A newborn with simmering bleeding after circumcision. Cureus 10(9): e3324.

- Breslin JW, Yang Y, Scallan JP, Sweat RS, Adderley SP, et al. (2018) Lymphatic vessel network structure and physiology. Compr Physiol 9(1): 207-299.

- Kundu PK, Cohen IM, Fluid mechanics. Conservation Laws, 16 Bernoulli Equations. (4th edn), Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands, p. 118.

- Belevich M (2017) Classical fluid mechanics. Perfect Fluid. 9.3.1. Bernoulli Equation. Bentham Science Publishers, Sharjah, UAE.

- Newton’s second law.

- George HF, Qureshi F (2013) Encyclopedia of tribology: Newton’s law of viscosity, Newtonian and non-Newtonian fluids. Springer, Boston, USA, p. 66.

© 2022 Mustafa Akman. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)