- Submissions

Full Text

Research in Pediatrics & Neonatology

Relationship Between Parent’s Secondhand Smoke and Growth of Infant Teeth

Taheri ES1, Sohrabi S2, Saeednia S3, Zolfaghari P4 and Sohrabi MB5*

1School of Medicine, Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, Iran

2School of Dentistry, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Iran

3Department of Basic Medical Sciences, School of Medicine, Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, Iran

4Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, Iran

5School of Medicine, Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, Iran

*Corresponding author: Mohammad Bagher Sohrabi, School of Medicine, Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, Shahroud, Iran

Submission: August 18, 2021; Published: November 23, 2021

ISSN: 2577-9200 Volume6 Issue1

Abstract

Background & aim: Cigarette smoke, due to its oxidative stress-causing substances, causes

undesirable changes in the infant tooth development and may cause delay in the growth of teeth. This

project was conducted with the aim of investigating the association between secondhand parent’s

smoking and growth of infant teeth.

Methods & materials: This is a case-control study that was conducted to determine the impact of

secondhand parents’ smoking and growth of infant teeth in children referred to the dental clinic of Bahar

Hospital of Shahroud in 2019. Eligible patients were selected by simple census method to complete the

sample size, based on having or not having a history of dental growth disorder, they were divided into

case and control groups and entered the study and history of secondhand parents’ smoking.

Results: The mean age of the children was 37.6±6.21 months. Exposure of secondhand parents’

smoking were 83 cases (80.6%) in the case group and 51 (49.5%) in the control group, which was

significantly higher (p=0.001) in the case group. It was found that secondhand smoking could significantly

increase the incidence of delay of teeth growth odds ratio [OR=1.55 (95% Confidence: 1.313-1.857)]

Conclusion: The results of this study showed that secondhand parent’s smoking can increase the

risk of delay of teeth growth and increase its odds ratio by about 1.5 times, but more definitive research

is needed to confirm this finding.

Keywords: Secondhand parent’s smoking; Teeth growth; Infant

Introduction

Smoking is one of the most common health problems; but not only its use but also exposure

to cigarette smoke can cause many harm to human beings; so even being exposed to cigarette

smoke increases the risk of lung cancer or cardiovascular disease [1]. Most of the effects

of smoking are caused by smoke. The effects of cigarette smoke are very diverse and affect

almost all body systems. People around the smoker are also unaware of these side effects and

are being treated as secondhand smoking [2]. Some people with special conditions are more

sensitive and suffer more complications. Elderly people with underlying illnesses, patients

taking over-the-counter medications, infants and children, are more susceptible to cigarette

smoke [3,4]. Some of these complications are not diagnosed even at birth and develop in

different forms as the child grows older [5]. One of the most likely injuries caused by exposure

to secondhand smoke is the developmental disorders of infants and toddlers, especially those

who have not only physical but also mental health problems [5,6]. Problems such as abnormal

weight gain, increased risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), leukemia, respiratory

diseases such as bronchitis and asthma, middle ear infections, and increased risk of delayed

tooth growth and premature decay are some of the problems associated with exposure to

secondhand smoke [7]. Cigarette smoke causes undesirable changes in infant teeth due to

stress-induced stimulants such as quinine [7,8].

Therefore, exposure to secondhand smoke is expected to not

only increase the risk of oxidative stress on the body, but also

increase the risk of dental disorders, especially growth retardation.

At about 6 months of age, develops the first milk teeth, which are

two teeth in the middle of the lower jaw. The normal time to start

and grow milk teeth is between 5 and 7 months, but a child may

have a tooth erupted much earlier than this, for example, at one

month of age or the onset of teething may be delayed until age of

18 months, which is normal. The validity of this finding in previous

studies on smoking in parent’s showed that the delay in the growth

of children, improper weight gain of the child and the delay in the

growth of milk teeth in infants of smoking parents are higher than

those who did not smoke [9]. However, there is insufficient and

documented information about the effects and risks of secondhand

smoking in breastfeeding parents. However, in some societies

up to 69% of infant are exposed to cigarette smoke at home [10,11].

In this regard, not only cigarette smoking, but also the rate of

cigarette smoking has been effective so that the consumption of

less than 10 cigarettes per day by the parents is 1.04 times and the

consumption of more than 10 cigarettes per day by the parents

up to 1.8 times increases the risk of adverse infant development

outcomes compared to non-smoking parents in infant exposed to

cigarette smoke [12]. Given the importance of the issue, the high

prevalence of smoking in society, the present study was conducted

to survey the association between secondhand parent’s smoking

and growth of infant teeth in children referred to the dental clinic

of Bahar Hospital in Shahroud, Iran.

Materials & Methods

The present study was received an ethics code number (IR.

SHMU.REC.1398.089 on 12.3.2019) from Research Deputy of

Shahroud University of Medical Sciences. The essential information

and the objectives of the study were explained to the parents of the

patients, and written consent was obtained for participation in the

plan.

This study is an intervention study in a human sample and in

order to determine the relationship between the developmental

disorder of infant teeth and parent’s smoking, children referred

to the dental clinic of Bahar Hospital in Shahroud were included

between January and December 2019. In this study, eligible children

were selected by simple census method to complete the sample

size, based on having or not having a history of the developmental

disorder of milk teeth, they were divided into case and control

groups and entered the study. The case group included those who

already had or had a history of the developmental disorder of milk

teeth. The development of deciduous teeth begins in the embryonic

period. Evidence of the development of teeth can be seen in the

sixth week of embryonic life. At birth, the baby has 20 milk teeth

or temporary teeth (10 in the upper jaw and 10 in the lower jaw)

that are hidden in the jawbone and under the gums. The normal

time to start teething in most children is between 4 and 7 months.

Of course, growth time is not the same in all children, and in some

children it may occur earlier than 4 months or later than one year,

which is perfectly normal. The first baby tooth to grow is usually

the anterior middle tooth of the mandible. The growth of deciduous

teeth is usually complete by the end of three years of age, at which

time the child has 20 deciduous teeth.

Although the time of eruption is different, the order of eruption

of deciduous teeth is usually as follows:

1. The two anterior middle teeth of the mandible (Lower incisors)

are usually the first teeth to grow and usually occur between 6

and 10 months of age.

2. The growth of the two anterior teeth of the middle upper

jaw (Upper incisors), which usually occurs between 8 and 13

months.

3. Then the later anterior teeth of the upper and lower jaw

(Lateral incisor) usually grow between 8 and 16 months of age,

in most cases the mandibular teeth tend to grow earlier.

4. The first and lower premolars milk teeth usually grow between

the ages of 13 and 19 months.

5. Upper and lower jaw deciduous biting teeth (Capsid) usually

occur between the ages of 16 and 23 months.

6. Finally, the teeth of the molar milk mill grow between the

ages of 25 and 33 months. Disorders in the development of

deciduous milk teeth are diagnosed by delaying the eruption of

each of these teeth, fewer of each of the above teeth, insufficient

longitudinal growth of each tooth, severe loosening of the

tooth that led to its fall, and abnormal tooth growth in its place.

Also malnutrition, vitamin D deficiency, and thyroid hormone

disorders will also be considered in all infants. To measure the height

and weight of each subject, the following standard procedures, were

measured using digital weighing scale and anthropometric rod to

the nearest 0.1kg and 0.1cm, respectively. Children whose weight for

age was less than two Standard Deviations (SD) below the median

were classified as underweight, children or wasted, respectively.

Then the children in both groups were asked about secondhand

smoking history and come with demographic information included

age, weight, the number of teeth available, the time of eruption of

each tooth, type of nutrition, history of dental development disorder

in other children and parents educational level was registered in a

special sheet. In this study, we included infants who were exposed

at least three months with a smoker (father, mother or both). In

terms of exposure, children were divided into three groups (Low: consumption of less than 5 cigarettes in 24 hours by parents,

Medium: consumption of 5 to 10 cigarettes in 24 hours and High:

consumption of more than 10 cigarettes in 24 hours).

Descriptive statistics including mean and standard deviation,

as well as relative frequency were used to describe the data.

To examine the relationships and comparisons between the

two groups, was used the chi-square test. Multivariate logistic

regression was used to evaluate the odds of each of the variables.

All analyzes were performed using SPSS software version 16. (p

<0.05) was considered to be significant. Sample size using Epi info

7.2 at a significant level of 5% and a power of 80%, equal to 103

people in each group and a total of 206 people.

Results

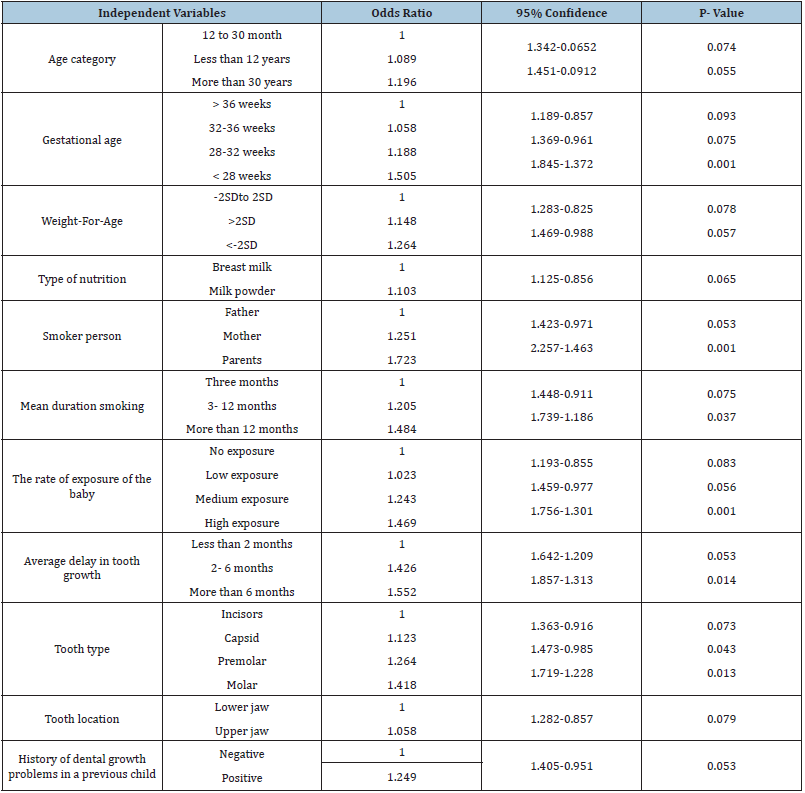

In this study, the mean age of patients was 37.6±6.21 months and the age group of 36-48 months with 43.1% had the highest frequency among children in both groups. It was also found that 53 children (22.7%) had no exposure to secondhand smoke or cigarettes. There was a significant difference between the two groups in terms of second-hand tobacco use (P <0.001). The results of second-hand smoking among infants in both groups are shown in Table 1. In this study, independent variables with dental growth disorder of infants were examined in a multivariate regression model. As shown in Table 2, tobacco use variables had a significant relationship with dental growth disorder, both parents are smokers, the average smoking time is more than 12 months, gestational age of infant, high exposure of baby, and delayed growth of pre-molar and molar teeth and there was no significant relationship with other variables. The results of the multivariate logistic regression model are presented in Table 2.

Table 1: Frequency distribution of children based on the exposure to secondhand smoke.

Table 2: Relationship between independent variables with delay in tooth growth in multivariate logistic regression model.

Discussion

The results of this study showed that, among the measured

variables, secondhand smoking significantly increased the risk of

delay in tooth growth in infants. The rate of this disorder is related

to factors such as the simultaneous smoking of parents, the duration

of smoking and also the daily consumption of cigarettes. This

finding is consistent with the results of Carvalho JC [13]. Of course,

given the limited scope of this study, the result cannot be attributed

to the entire community, but it can highlight the importance of

the need for greater attention and more comprehensive research.

Smoking by parents during infancy can cause problems such

as breathing problems, hypersensitivity, asthma exacerbations,

mental development problems and delayed growth of infants and

children [14]. Parents’ smoking around their young children is

declining in developed countries, but is strongly associated with

cultural and economic poverty, and is on the rise in low-income

or middle-income countries. Smoking is typically reported to be

low in lactating women or women with young children. However,

many infants are exposed to secondhand smoke that can affect

their growing physical and mental health [15]. In some studies,

exposure to second-hand smoking during infancy increases the

risk of respiratory distress in infants by 23% and growth and

developmental abnormalities by 13% and reduces infant weight

gain [16,17]. One study also found a significant association between

parental smoking and infant longitudinal growth limitation [18].

The study found that the younger the gestational age of baby

(especially gestational age less than 28 weeks), the more likely it

was that dental malformations will occur in the face of secondhand

smoke. Perhaps the most important reason is the lower resistance

and safety of these children to the effects of cigarette smoke.

Biological age may be effective in causing apoptosis of the tissues

around the tooth and slowing their growth. Tobacco constituents

enhance apoptosis in periodontal tissue. These findings are

consistent with the study conducted by the Ramos SR et al. [19]

and Kang SW et al. [20]. In this study, it was found that the growth

of children’s teeth exposed to secondhand smoke was significantly

delayed, and this delay was greater in the premolar and molar teeth.

In the study of Lee SI et al. [21] it was found that smoking in parents

with complications of infancy, in particular, delays in the child’s

development, such as when to sit and walk the power of learning

and completing the number of children’s teeth, especially grinding

teeth, is higher than that among normal people. In the study of

Semlali A et al. [22] smoking daily increases the risk of delaying the

growth of a child’s first teeth, and smoking-related illnesses such

as respiratory illnesses can be thought to exacerbate or exacerbate

dental growth problems.

The study found that if both parents were smokers, they

were much more likely to develop dental growth disorders. This

is because children are more prone to secondhand smoke. A

study by Riedel C et al. [23] among children with developmental

disorders, such as problems with tooth growth, showed that the

high prevalence of secondhand smoking was found to be similar

to the results of this study. In this study, it was found that the

effect of secondhand smoking on tooth growth in depending on

the exposure to secondhand smoke was significantly different, as

the amount of exposure increases (high exposure), the problems

related to the growth of teeth increase significantly. The results of

Zadzińska E et al. [24] were in perfect agreement, but the results of

Hammond and Meeker’s studies showed that rate of impairment of dental growth was significantly higher even at moderate doses.

This may be due to the type of participants selected or the sample

size of the studies [18,19].

This study found an impact of secondhand smoking on incidence

of tooth growth delay in various children’s weight group; although

the group of children who weighed less than the corresponding age

group was higher, there was no significant difference between them.

Children who are the right weight for their age are less likely to be

affected by secondhand smoke due to a better and more complete

immune system. This finding is inconsistent with the findings of Li

MY et al. [25] study, which found that children’s weight did not affect

their susceptibility to the effects of cigarette smoke, which may be

due to their choice of children to study [25]. The results of this

study showed that by increasing the duration of smoking by parents

(especially more than one year), the likelihood of delayed dental

growth increases. It was also found that if a child is high exposed to

secondhand smoke, the chances of delaying tooth growth are much

higher. This finding is consistent with the results of Ershoff DH et

al. [11] and Huang R et al. [12] studies but contradicts the findings

of the Molnar study that increase in exposure to secondhand smoke

has not had a significant effect on delayed tooth growth, which may

be due to differences in children’s choice or sample size [18]. In

reviewing the logistic regression model regarding factors affecting

delay of tooth growth, it was found that secondhand smoking (odds

ratio, OR=1.5) increased the chance of tooth growth delay. These

findings are consistent with the results of Zadzińska E et al. [24]

and with the results of Li MY et al. [25] and Williams SA et al. [26]

to some extent. The most important reason for the incomplete

outcome of these results may be the type of study designed or the

sample size to be evaluated.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that the rate of delayed dental growth in the group of children with smoking parents is relatively high. It has also been shown that second-hand smoking can increase the likelihood of delayed dental growth. Because second-hand smoking increases children’s dental development problems, controlling and reducing smoking during pregnancy and lactation may significantly reduce the incidence of pediatric dental complications. Therefore, in order to control and prevent the inappropriate growth of teeth in children due to smoking by parents, it is necessary to emphasize the non-smoking during pregnancy and lactation by parents and relatives. It is also important to improve the attitudes and actions of parents and their loved ones about the effects of smoking or smoking around young children.

Limitations

One of the limitations of this research is the self-report of parents in smoking, as well as children’s dental disorders, and especially the delay in tooth growth, which has sometimes not been enough. This problem has been largely solved by justifying parents and repeating the question. Another limitation is that insufficient data on the dose were not available to assess the dose-response relationship and the time it took for cigarette smoke to assess the extent of the damage. Also, the cases in the two groups were divided only in terms of the history of delay in tooth growth, and in other cases, the matching between the two groups was not performed.

References

- Farjamfar M, Moradnia M, Zolfaghari P, Shariyati Z, Sohrabi MB (2020) Association between panic attacks and cigarette smoking among psychiatric patients. J Public Health (Berl) 28: 65-69.

- Hanioka T, Ojima M, Tanaka K, Taniguchi N, Shimada K, et al. (2018) Association between secondhand smoke exposure and early eruption of deciduous teeth: A cross-sectional study. Tob Induc Dis 16: 04.

- Best D, Committee on Environmental Health, Committee on Native American Child Health, Committee on Adolescence (2009) From the American academy of pediatrics: Technical report--secondhand and prenatal tobacco smoke exposure. Pediatrics 124(5): e1017-e1044.

- Vardavas CI, Hohmann C, Patelarou E, Martinez D, Henderson AJ, et al. (2016) The independent role of prenatal and postnatal exposure to active and passive smoking on the development of early wheeze in children. Eur Respir J 48(1): 115-124.

- Tanaka K, Miyake Y, Furukawa S, Arakawa M (2017) Secondhand smoke exposure and risk of wheeze in early childhood: A prospective pregnancy birth cohort study. Tob Induc Dis 15: 30.

- Hanioka T, Ojima M, Tanaka K, Yamamoto M (2011) Does secondhand smoke affect the development of dental caries in children? A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 8(5): 1503-1519.

- Bernabé E, MacRitchie H, Longbottom C, Pitts NB, Sabbah W (2017) Birth weight, breastfeeding, maternal smoking and caries trajectories. J Dent Res 96(2): 171-178.

- Featherstone JD (2004) The continuum of dental caries--evidence for a dynamic disease process. J Dent Res 83(Spec Iss C): C39-42.

- Avsar A, Topaloglu B, Hazar-Bodrumlu E (2013) Association of passive smoking with dental development in young children. Eur J Paediatr Dent 14(3): 215-218.

- Chowdhury IG, Bromage TG (2000) Effects of fetal exposure to nicotine on dental development of the laboratory rat. Anat Rec 258(4): 397-405.

- Ershoff DH, Solomon LJ, Dolan-Mullen P (2000) Predictors of intentions to stop smoking early in prenatal care. Tob Control 9(Suppl 3): III41-45.

- Huang R, Li M, Gregory RL (2015) Nicotine promotes Streptococcus mutans extracellular polysaccharide synthesis, cell aggregation and overall lactate dehydrogenase activity. Arch Oral Biol 60(8): 1083-1090.

- Carvalho JC (2014) Caries process on occlusal surfaces: Evolving evidence and understanding. Caries Res 48(4): 339-346.

- Tanaka K, Miyake Y, Nagata C, Furukawa S, Arakawa M (2015) Association of prenatal exposure to maternal smoking and postnatal exposure to household smoking with dental caries in 3-year-old Japanese children. Environ Res 143(Pt A): 148-153.

- Tanaka S, Shinzawa M, Tokumasu H, Seto K, Tanaka S, et al. (2015) Secondhand smoke and incidence of dental caries in deciduous teeth among children in Japan: Population based retrospective cohort study. BMJ 351: h5397.

- Aktoren O, Tuna EB, Guven Y, Gokcay G (2010) A study on neonatal factors and eruption time of primary teeth. Community Dent Health 27(1): 52-56.

- Żądzińska E, Sitek A, Rosset I (2016) Relationship between pre-natal factors, the perinatal environment, motor development in the first year of life and the timing of first deciduous tooth emergence. Ann Hum Biol 43(1): 25-33.

- Molnar DS, Rancourt D, Schlauch R, Wen X, Huestis MA, et al. (2017) Tobacco exposure and conditional weight for-length gain by 2 years of age. J Pediatr Psychol 42(6): 679-688.

- Ramos SR, Gugisch RC, Fraiz FC (2006) The influence of gestational age and birth weight of the newborn on tooth eruption. J Appl Oral Sci 14(4): 228-232.

- Kang SW, Park HJ, Ban JY, Chung JH, Chun GS, et al. (2011) Effects of nicotine on apoptosis in human gingival fibroblasts. Arch Oral Biol 56(10): 1091-1097.

- Lee SI, Kang KL, Shin SI, Herr Y, Lee YM, et al. (2012) Endoplasmic reticulum stress modulates nicotine-induced extracellular matrix degradation in human periodontal ligament cells. J Periodontal Res 47(3): 299-308.

- Semlali A, Chakir J, Goulet JP, Chmielewski W, Rouabhia M (2011) Whole cigarette smoke promotes human gingival epithelial cell apoptosis and inhibits cell repair processes. J Periodontal Res 46(5): 533-541.

- Riedel C, Schönberger K, Yang S, Koshy G, Chen YC, et al. (2014) Parental smoking and childhood obesity: Higher effect estimates for maternal smoking in pregnancy compared with paternal smoking--a meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol 43(5): 1593-1606.

- Zadzińska E, Nieczuja-Dwojacka J, Borowska-Sturgińska B (2013) Primary tooth emergence in Polish children: Timing, sequence and the relation between morphological and dental maturity in males and females. Anthropol Anz 70(10): 1-13.

- Li MY, Huang RJ, Zhou XD, Gregory RL (2013) Role of sortase in Streptococcus mutans under the effect of nicotine. Int J Oral Sci 5: 206-211.

- Williams SA, Kwan SY, Parsons S (2000) Parental smoking practices and caries experience in pre-school children. Caries Res 34(2): 117-122.

© 2021 Mohammad Bagher Sohrabi. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)