- Submissions

Full Text

Research in Pediatrics & Neonatology

Management of Impetigo in Children: A Review Article

Gofur NRP1*, Gofur ARP2, Soesilaningtyas3, Gofur RNRP4, Kahdina M4 and Putri HM4

1Department of Health, Faculty of Vocational Studies, Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia

2Faculty of Dental Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia

3Department of Dental Nursing, Poltekkes Kemenkes, Indonesia

4Faculty Of Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia

*Corresponding author: Gofur NRP, Department of Health, Faculty of Vocational Studies, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia

Submission: April 06, 2021; Published: June 09, 2021

ISSN: 2577-9200 Volume5 Issue5

Abstract

Introduction: Impetigo is a pyoderma, which is a skin infection caused by Staphylococcus aureus in the epidermis below the stratum corneum or in the hair follicles. Impetigo is an infectious skin disease most commonly found in children aged two to five years, but can also occur at any age. This disease can heal completely without scarring even without treatment. The cause of impetigo is a gram-positive bacterial infection, most commonly Staphylococcus aureus, but it can also be caused by Streptococcus pyogenes either as a single infection or in combination with S. aureus. It is most occur in children aged 2-5 years and incidence is during summer and fall. Bullous impetigo is more common in infants. Children younger than two had 90% of cases of impetigo. Apart from direct contact with an infected child, sharing tools or items that can transmit the infection can also spread impetigo. The incidence of impetigo increases in areas that are densely populated and with poor hygiene. Other risk factors include trauma to the skin, a hot and humid climate, malnutrition, diabetes mellitus, and several other medical conditions.

Discussion: Impetigo is usually a self-limited condition, and although rare, complications can occur. These include cellulitis (nonbullous form), septicemia, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, lymphangitis, lymphadenitis, guttate psoriasis, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, with poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis being the most serious. Keeping skin clean can help prevent impetigo. Kids should wash their hands well and often and take baths or showers regularly. Pay special attention to skin injuries (cuts, scrapes, bug bites, etc.), areas of eczema, and rashes such as poison ivy. Keep these areas clean and covered. The goal of impetigo therapy is to relieve discomfort and improve appearance/aesthetics, prevent the wider spread of infection both to the patient and to others, and prevent recurrences. Therapy should ideally be effective, affordable, and minimal side effects.

Conclusion: Based on research and some literature, impetigo can heal by itself without leaving a sequel within two weeks if left untreated. However, healing takes longer time and complications can occur in some cases. One of the complications that can be caused is post streptococcal acute Glomerulonephritis (GNAPS), sepsis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, endocarditis, pneumonia, cellulitis, lymphangitis or lymphadenitis, gutate psoriasis, toxic shock syndrome, and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.

Keywords: Impetigo; Children; Management

Introduction

Impetigo is a pyoderma, which is a skin infection caused by Staphylococcus aureus in the epidermis below the stratum corneum or in the hair follicles. Impetigo is an infectious skin disease most commonly found in children aged two to five years, but can also occur at any age. This disease can heal completely without scarring even without treatment [1]. The cause of impetigo is a gram-positive bacterial infection, most commonly Staphylococcus aureus, but it can also be caused by Streptococcus pyogenes either as a single infection or in combination with S.aureus. It is most occur in children aged 2-5 years and incidence is during summer and fall. Bullous impetigo is more common in infants. Children younger than two had 90% of cases of impetigo [2]. Impetigo is the most common bacterial skin infection in children and there are two types of impetigo. First is nonbullous (more frequent) and bullous. Nonbullous impetigo, or impetigo contagiosa, is caused by S.Aureus characterized by honey-colored crusts on the face and extremities. Impetigo primarily affects the skin or secondarily infects insect bites, eczema, or herpetic lesions [2]. Impetigo is often transmitted through direct contact. Patients can spread the infection more widely by scratching the infected area (autoinoculation). This infection can also easily spread in schools and child care centers. Apart from direct contact with an infected child, sharing tools or items that can transmit the infection can also spread impetigo. The incidence of impetigo increases in areas that are densely populated and with poor hygiene. Other risk factors include trauma to the skin, a hot and humid climate, malnutrition, diabetes mellitus, and several other medical conditions [3].

Discussion

Classification and diagnosis

Impetigo is generally classified into 2 types, namely bullous impetigo (30% of cases) and crustous/ nonbulous impetigo (70% of cases) [4]:

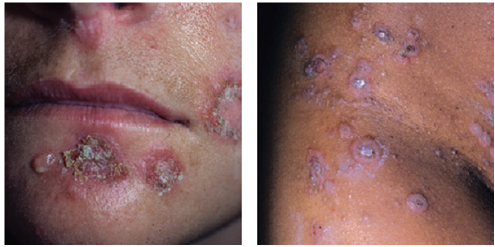

Bullous impetigo

Bullous impetigo often occurs in neonates but can also occur in children and adults. Bullous impetigo is caused by the toxinproducing S.aureus and is a localized form of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Bullous impetigo has a clinical feature of multiple vesicles that expand rapidly to form a well-defined, flaccid bullae without surrounding erythema. When the bullae rupture, yellowish crusts will appear. Bullous impetigo is often found in moist folds, such as the diaper area, axilla and neck creases. This disease can heal on its own in a few weeks without scarring [2] Figure 1.

Figure 1: Bullous impetigo: It appears that there are multiple vesicles to a flaccid bullae in which there is a yellowish fluid [2].

Crustous impetigo/non bullosa/contangiosa

Crustous impetigo occurs as a result of infection with Streptococcus pyogenes either alone or in combination with S.aureus. Crustous impetigo begins with the appearance of a single, reddish macule or papule that quickly turns into a vesicle. These vesicles then easily rupture and cause an erosion, which results in golden brown crusts that cause itching. Impetigo spreads by autoinoculation, which often appears to traumatized areas such as the extremities or face. This condition can heal itself without causing scars [5] Figure 2.

Figure 2: Impetigo Krustosa. There were golden brown vesicles and crusts with multiple blackish crusts. A) crustous impetigo of the face; B) impetigo crustosa in the groin [2].

In making a diagnosis of impetigo, it is necessary to carry out several stages, including [1,6]:

A. History

With symptoms that are often complained of in the form of itching and pain in the vesicle area. The history of contact with impetigo sufferers and other risk factors also needs to be explored.

B. Clinical features

The clinical picture of impetigo is typical, namely the presence of vesicles or bullae accompanied by crusts that break and easily spread, with crusts that are brownish yellow like honey, sometimes accompanied by black crusts that are often found in crustous impetigo.

\C. Supporting examination

Pus culture and gram stain and antibiotic sensitivity test if needed. Differential diagnosis of impetigo for bullous type is Bullous erythema multiforme, Bullous fixed drug eruption, Bullous lupus erythematosus, Thermal burns, Insect bites, Contact dermatitis, Necrotizing fasciitis. DD for non-bullous type is Atopic dermatitis, bockhart impetigo, Herpes simplex virus, Varicella zoster virus, Sweet syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis), Scabies and Pediculosis (lice) [3,7]. Impetigo is usually a self-limited condition, and although rare, complications can occur. These include cellulitis (nonbullous form), septicemia, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, lymphangitis, lymphadenitis, guttate psoriasis, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, with poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis being the most serious [8]. Keeping skin clean can help prevent impetigo. Kids should wash their hands well and often and take baths or showers regularly. Pay special attention to skin injuries (cuts, scrapes, bug bites, etc.), areas of eczema, and rashes such as poison ivy. Keep these areas clean and covered. Anyone in your family with impetigo should keep their fingernails cut short and the impetigo sores covered with gauze and tape. To prevent impetigo from spreading among family members, make sure everyone uses their own clothing, sheets, razors, soaps, and towels. Separate the bed linens, towels, and clothing of anyone with impetigo, and wash them in hot water. Keep the surfaces of your kitchen and household clean [3,9].

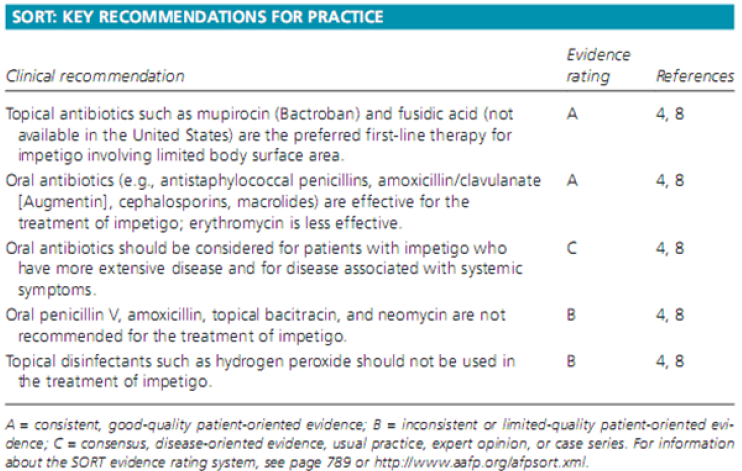

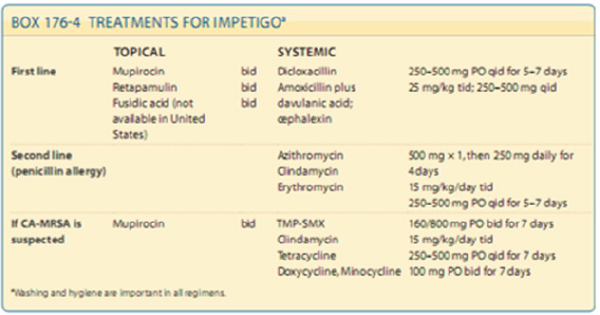

Management of Impetigo in Children

The goal of impetigo therapy is to relieve discomfort and improve appearance/aesthetics, prevent the wider spread of infection both to the patient and to others, and prevent recurrences. Therapy should ideally be effective, affordable, and minimal side effects [10,11] Figure 3. Therapy that can be used includes both topical and oral antibiotics. As a supportive therapy, compress the wound with disinfectant or isotonic saline and improve personal hygiene. Topical antibiotics have the advantage of applying only when needed, which minimizes antibiotic resistance and reduces the likelihood of systemic side effects. The duration of topical antibiotic therapy varied, however, seven days of administration showed more effective results. However, some topical antibiotics can cause both skin sensitization and allergies in susceptible patients [12]. Oral antibiotics are recommended in patients who cannot be given topical antibiotics and in patients with systemic symptoms such as fever and in extensive lesions. The choice of antibiotics that can be used in cases of impetigo is summarized in Figure 4 [13,14]. In several studies, topical antibiotics such as mupirocin have the same effectiveness as some oral antibiotics such as dicloxacillin, cephalosporins, and ampicillin.

Figure 3: Clinical recommendations for the management of impetigo [2,11].

Figure 4:First-line and second-line treatment of impetigo [1].

Conclusion

Based on research and some literature, impetigo can heal by itself without leaving a sequel within two weeks if left untreated. However, healing takes longer time and complications can occur in some cases. One of the complications that can be caused is post streptococcal acute Glomerulonephritis (GNAPS), sepsis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, endocarditis, pneumonia, cellulitis, lymphangitis or lymphadenitis, gutate psoriasis, toxic shock syndrome, and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.

References

- Craft N (2012) Superficial cutaneous infections and pyodermas. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, (Eds.), Fitzpatrick’s dermatology in general medicine, (8th edn), McGraw-Hill, New York, USA, 176: 2129-2133.

- Cole C, Gazewood J (2007) Diagnosis and treatment of impetigo. Am Fam Physician 75: 859-864.

- Hartman-Adams H, Banvard C, Juckett G (2014) Impetigo: Diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician 90(4): 229-235.

- Mancini AJ (2000) Bacterial skin infections in children: The common and the not so common. Pediatr Ann 29(1): 26-35.

- May PJ, Tong SYC, Steer AC, Currie BJ, Andrews RM, et al. (2019) Treatment, prevention and public health management of impetigo, scabies, crusted scabies and fungal skin infections in endemic populations: A systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 24(3): 280-293.

- Sahu JK, Mishra AK (2019) Ozenoxacin: A novel drug discovery for the treatment of impetigo. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 16(3): 259-264.

- Bangert S, Levy M, Hebert AA (2012) Bacterial resistance and impetigo treatment trends: A review. Pediatr Dermatol 29(3): 243-248.

- Luby SP, Agboatwalla M, Feikin DR, Painter J, Billhimer W, et al. (2005) Effect of handwashing on child health: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 366(9481): 225-233.

- Loadsman MEN, Verheij TJM, Velden AW (2019) Impetigo incidence and treatment: A retrospective study of Dutch routine primary care data. Fam Pract 36(4): 410-416.

- Koning S, Sande R, Verhagen AP, Suijlekom-Smit LW, Morris AD, et al. (2012) Interventions for impetigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1(1): CD003261.

- Smith DRM, Dolk FCK, Pouwels KB, Christie M, Robotham JV, et al. (2018) Defining the appropriateness and inappropriateness of antibiotic prescribing in primary care. J Antimicrob Chemother 73(suppl_2): ii11-ii18.

- Rush J, Dinulos JG (2016) Childhood skin and soft tissue infections: New discoveries and guidelines regarding the management of bacterial soft tissue infections, molluscum contagiosum, and warts. Curr Opin Pediatr 28(2): 250-257.

- Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RS, Fridkin SK, et al. (2011) Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: Executive summary. Clin Infect Dis 52(3): 285-292.

- Rosen T, Albareda N, Rosenberg N, Alonso FG, Roth S, et al. (2018) Efficacy and safety of ozenoxacin cream for treatment of adult and pediatric patients with impetigo: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol 154(7): 806-813.

© 2021 Gofur NRP. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)